Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Or, Beat, Prey, Love: How Arkane combines holistic level design and dynamic enemies to great effect in Prey.

There’s a cute bit in the Philip K. Dick story “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” where one character warns another about the lurking threat of kipple, all the useless objects that clutter up our lives.

“When nobody’s around, kipple reproduces itself,” he says. “No one can win against kipple, except temporarily and maybe in one spot, like in my apartment...but eventually I'll die or go away, and then the kipple will again take over. It's a universal principle operating throughout the universe; the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization.”

Games are full of kipple. Empty cardboard boxes, old crates, coffee mugs, desks piled high with papers you can’t read and manila folders you can never open.

But Arkane’s latest, Prey, does something neat with kipple -- it weaponizes it.

Like most games you might call "immersive sims" (Deus Ex, Thief, BioShock, System Shock), Prey asks players to spend a lot of time rooting around in cabinets, trash cans and other nooks/crannies in search of hidden gems: useful resources buried in the rubbish.

Unlike those other games, Prey makes that rote and repetitive action scary. It introduces an enemy early on called the Mimic, a common but utterly alien creatures that tends to hide by taking the form of a piece of kipple, then leaping out when the player draws close.

While the nuts and bolts of actually fighting Mimics once they’re revealed can be annoying (they’re small and move erratically), their sheer existence make every otherwise innocuous, kipple-strewn corner of Prey’s Talos I space station feel threatening and alive.

And shucks, that space station. Can we just take a minute to appreciate the way Prey handles space, and sets the player up to tell their own stories within it?

The game came out a month ago at this point and I know it may have slipped past a lot of people (there are a lot of games!) but after finishing it, I wanted to quickly call out some of the neat things Prey does that are worth celebrating.

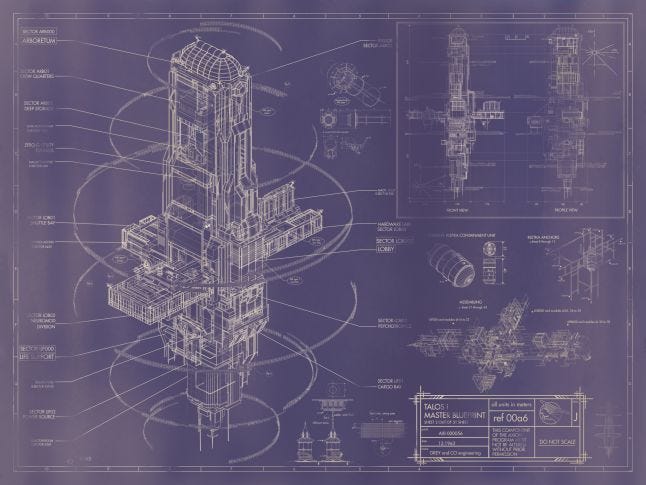

Prey takes place on Talos I, a fictional space station orbiting Earth’s moon. Once the player moves past the opening scene, pretty much the entire station is accessible, and the player can also get outside and jet around the station’s exterior (though they take damage if they go too far.)

That means pretty much every space in the game is understandable and accessible from multiple perspectives, both internally and externally.

A player can spend five hours moving through the station from the Arboretum to the Hardware Labs, then exit into space through an airlock and retrace their path externally in a few minutes. If they happen to float by a viewport on the way, they might glimpse the aftermath of a particularly frenetic fight they had two hours ago, or spot the open hatch of a maintenance duct they crawled through to circumvent said fight.

This is important because it reinforces the illusion that the player is somewhere else. It makes Talos I feel like a real place, a holistic environment that can be explored, learned, and mastered.

This kind of environmental design isn’t easy -- there’s a reason most games run through a linear series of discrete levels -- but when done right, it helps the player feel embodied in your game.

There are lots of great examples of other games that nail this sort of holistic level design, but I’m just going to take the lazy way out and say it’s like Dark Souls. That game had fantastic, complicated environments that all fit together perfectly, lulling players into feeling that they were exploring a real place. Prey achieves something very similar, with the added benefit of being set on a floating space station that can be circumnavigated from the outside.

Also like Dark Souls, the lion’s share of Prey is devoid of friendly life. Thus, the game's interlocking environments are chiefly defined by what enemies you find there and what stuff you can pick up.

The enemies also respawn or repopulate across Talos I in some fashion, ensuring (for better and for worse) that players can never fully relax when backtracking. More importantly, there are moments when the nature and number of enemies spread across the station changes in accordance with the narrative.

That gives players new challenges in known settings, keeping those locations feeling fresh and, more importantly, rewarding players for learning and exploiting the environments of Talos I.

Prey takes a lot of direct inspiration from games like System Shock, Thief, and Deus Ex, asking players to navigate Talos I while fighting/tricking/sneaking past enemies and collecting items, weapons and upgrades.

Since those resources are placed throughout the station and basically the whole thing is open to players from the jump, there are lots of different paths players can carve through the game -- and lots of ways that progression can be impacted by how threats shift and change.

For example, let me lay out my emotional journey through Prey. After about an hour, I was intrigued and felt pretty safe: I had plenty of healing items, a weapon or two, and (naive) trust that the game’s designers had balanced the difficulty level (Normal) so that I couldn’t totally ruin myself.

This seems fine

Five hours in, I was ruined.

I’d burned through all of my healing items, ammunition, and upgrade tools. All I had left was a wrench and a few EMP grenades, which were useless against the monstrosities that stood between me and everything I needed -- a shotgun, for example, or the fabrication plans for medkits.

I considered restarting the game, but decided to stick with it and sneak past everything in my way. I was terrified. Prey was the worst!

Ten hours in, Prey felt too easy. I’d managed to get both a shotgun and the medkit plans, as well as some schematics for other Useful Things. I was practically bursting with ammo and healing items, and I’d learned the enemies and environments well enough to know no fear.

This is it, I thought. This is the part in every game where you make the jump from underpowered to overpowered. Assuming the endgame was nigh, I caught myself thinking wistfully about how much more immersive and real Talos I had felt when I was inching through it in total abject terror. It would be kind of nice to go back to being underpowered, I thought.

Twenty hours in, I decided it wasn’t actually that nice! I was totally out of healing items (again), out of ammo (again!) and barely surviving as I sprinted across the station, using every trick I knew to try and get away from the enemy.

By this point I’d cleaned out most of Talos I and was having a hard time replenishing my resources and getting from zone to zone, much less accomplishing quest objectives. With no immediate endgame in sight, I thought again about giving up -- or at least reloading an earlier save.

After ~26 hours of play, I finished Prey. I had to make some late-game upgrade choices to counter troublesome enemies, and chase some side objectives that took me through new (resource-rich) areas of the station, but at the end I felt, if not godlike, at least god-ish.

Most games like this take you from the same start to the same end; the player starts at the bottom of a smooth power curve and spends the game climbing to the top. Prey stands out because it affords the player space to slip, fall, and get back up again, only to slip up in a totally new and terrifying way.

I mean space in a literal sense as much as a figurative one. When lead designer Ricardo Bare talked to Gamasutra earlier this year about the team’s approach to level design, he said the goal was to create a kind of “mega-dungeon” in space “with lots of immersive, simulation-based systems.”

Enter the Mega-Dungeon

Enter the Mega-Dungeon

By way of example he mentioned the studio’s 2002 first-person RPG Arx Fatalis, which took place inside a giant network of caves.

But my dumb stupid brain went somewhere else -- to the sorts of “mega-dungeons” that are popular in some tabletop role-playing game circles, especially in the 20th century.

If you didn't play D&D or whatever in the '90s, know that these were often sprawling, isolated areas with ridiculously complicated layouts (think like, a 12-level underground dungeon surrounded by a network of caves) and, most importantly, threat levels that varied depending on how far players were willing to explore.

That means players could effectively set their own difficulty by choosing how deep to delve. Pair that with the relative freedom tabletop RPGs afford players in choosing how to circumvent challenges, and you get an experience that's often light on narrative (there's something real bad going on in these caves/dungeons/ruins! Check it out!) but well-suited to letting players tell the story they want to tell.

Making games that give players lots of room to tell their own stories is tricky business. I think if you look at Prey, you'll find some good examples of how that can be done well.

Players can go almost anywhere and do almost anything (including finishing the game) relatively early on, but Talos I’s interconnected environments are filled with enemies of varying difficulty, letting players choose how to play and what to risk. The threats in those environments change over time, rewarding players for learning the levels and increasing the odds they’ll go through dramatic shifts in power level as they adapt to new challenges.

Of course, there’s a big downside to all this that you’ve probably already sussed out. Prey gives the player finite resources, but the enemies seem nigh-infinite. You might clear out a section of the station, only to come back hours later and find fresh monstrosities lying in wait for you.

That has a chilling effect on the player’s creativity; after all, why risk experimenting with new weapons and tactics when you know that freezing an enemy with the industrial-strength glue gun and bashing them to death with your wrench will A) be ammo-efficient B) totally work and C) present minimal risk of damage?

70 percent of the time, this works every time

This problem really rears its head in the end-game, when the player is likely to be criss-crossing Talos I and facing new enemies while moving through spaces that have already been picked clean.

Still, it's a minor complication in an otherwise great example of good level design and interesting power/challenge systems. I know a ton of interesting games will come out this year (like every year!) but if you have the means to take a look at Prey, do so!

And if you want a bit more from Ricardo “Mega-Dungeon” Bare, check out this hour-long conversation Gamasutra Editor-In-Chief Kris Graft and Contributing Editor Bryant Francis had with him while streaming Prey on our Twitch channel last month. (I’m not in it, so it should be pretty watchable!)

Alternate blog titles: Beat, Prey, Love; Prey You Catch Me; Let Us Prey; The Prey's The Thing

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like