Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This article discusses Elephant Mouse's experience with prototyping core game mechanics for their mobile puzzle game - Robots Need Love Too! Read about their highs and lows with this key part of pre-production.

Introduction

Elephant Mouse (www.elephantmouse.com) is a mobile game development studio proudly located in the Research Triangle of Raleigh, North Carolina, a hotbed of tech innovation, game development, and tasty BBQ. EM veterans hail from the likes of Activision, Ubisoft, EA, Playdom, Zynga, and other industry giants. We’ve released several highly-rated mobile titles, including Star Trek™ Rivals, The Godfather Slots, Lil’ Birds, and Archetype.

Robots Need Love Too is our new game that will be launching in September. A lite version is currently available in the Canadian App Store. If you are in Canada, please give it a try and let us know what you think!

The Setup for our New Game

We wanted to create a fun new puzzle game for mobile devices, and we wanted to target a casual audience who enjoy indie games. The entire team was invited to pitch concepts and prototypes, and we brainstormed tons of concepts.

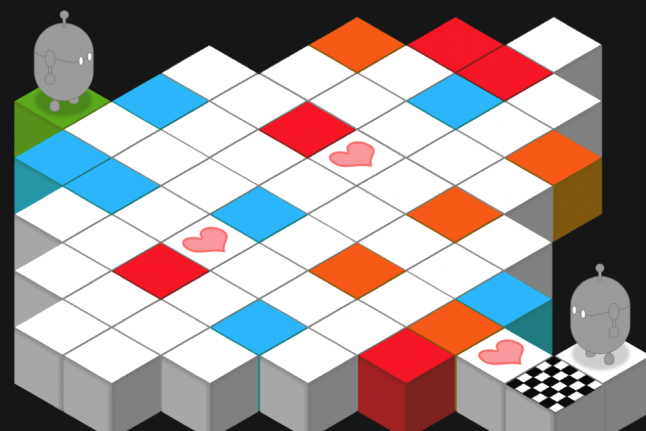

One of the programmers created a playable prototype in Unity about robots in love. It was a side-view physics puzzler where the player tried to get two robots to meet. Though we liked the concept, we wanted to move away from physics-based games (because we thought that would be a lot of work for our small team). We kept the idea of robots, how they meet up at the end of each level, and the game name - Robots Need Love Too.

We focused on the mechanic of setting up actions, then activating the sequence to see what happens. Then our designer fleshed out some initial mechanics involving directional arrows. The whole concept was structured around a narrative of forbidden love (the best kind).

Initial Prototype

3-Heart Solution

Green Square [ ↑ ]

Blue Square [ ↱ ]

Orange Square [ ↰ ]

Red Square [ ↷ ]

Robots need prototypes, too! The team's designer took a day and created an initial paper prototype in Photoshop of a sample puzzle featuring a grid and colored squares. In this version, each colored square represented a direction that the robot would move (right, left, straight, U-turn). The player had to pair up the directional arrow with the appropriate color in order to create a path to get the robot to the checkered tile. Team members played the game and verbally shared their feedback with the designer.

We all liked this basic mechanic and decided to iterate on it further. Madness ensued.

Second Iteration

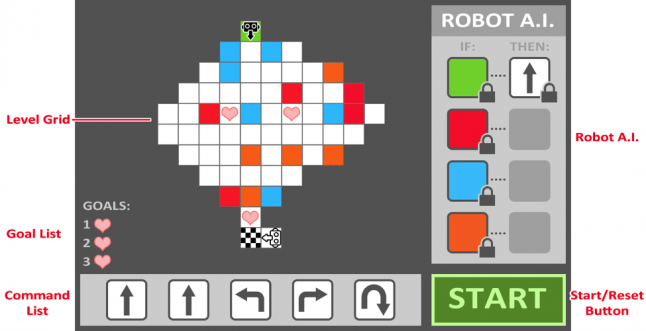

In this version, the designer created a more detailed spec so that engineering could create a digital prototype. It took roughly 2 days to build this prototype.

The player's goal was to solve the puzzle by assigning the correct directional arrow to a particular color -- getting the black robot to the checkered tile. Some touch-screen friendly UI was added, because we really wanted to make sure the controls felt smooth on a mobile device. The player still only controlled one robot. A heart-collecting mechanic was added. The player could add to the challenge by trying to collect all three hearts on the way to the goal tile. We figured that the heart-collecting mechanic was a good way to add difficulty into the puzzles.

We did some internal play testing and were happy with the results. It seemed that we had an interesting mechanic that we could build on.

Third Iteration

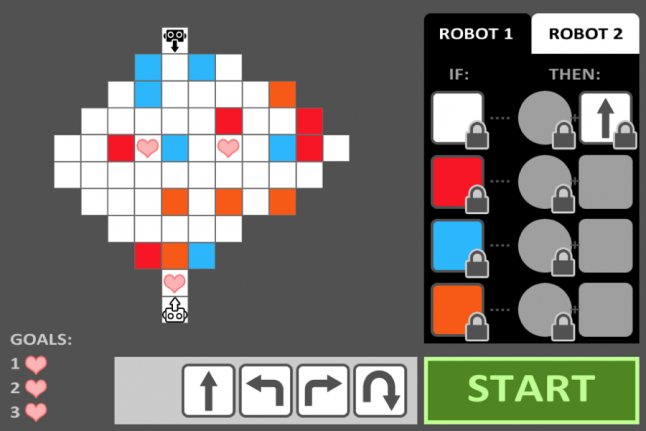

In this iteration, a second robot AI was added. Now the player could control both robots! Making changes to this prototype took roughly 3 days. The team believed that adding this feature would give the player a fun challenge and really play up the romantic aspect of the story. Obstacles were also added, which the player had to account for when creating the navigation path. The designer experimented with several different mechanics and obstacles to add variety to the game play. We kept the heart-collecting mechanic.

At this point, we did some friend-and-family testing to get reactions on the puzzles. We had a small test group (a half-dozen people). The feedback was useful, but not definitive. Some people really loved the game play, whereas others enjoyed it, but thought that the difficulty ramped up quickly when other obstacles were added. It was also difficult for the player to toggle between the two robots and set up the paths. The UI didn't make it clear which robot was active. Finally, it was difficult for players to figure out where to place the arrows and other obstacles to create the path. Back to the drawing board!

Fourth Iteration

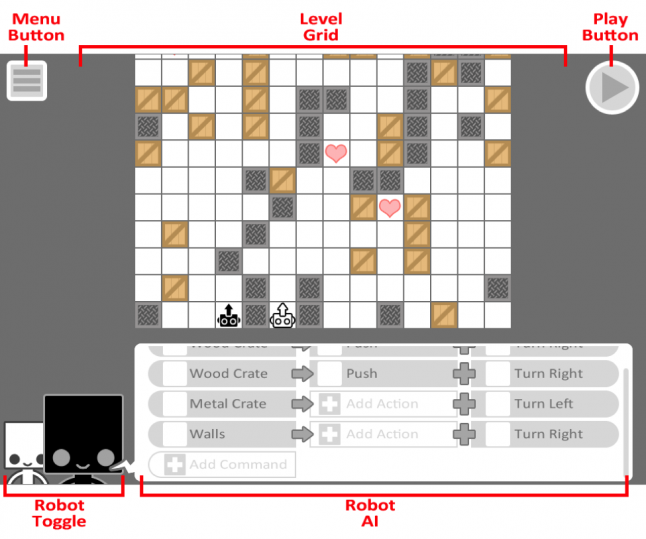

Based on this feedback, the designer changed the UI completely. In this version, the player could clearly see which robot was active, and could easily toggle between them. The designer also invented a new system for chaining commands together. This version took 7 days to complete since it involved a total re-design of the UI.

The colored tiles were removed and replaced with things that made more sense for the game world: wooden and metal crates! Now the player could determine what action the robot would take when reaching a particular place in the level. We still kept the heart-collecting mechanic; that worked really well for all the prototypes, and it added another layer of challenge for more advanced players.

We did additional friend-and-family testing and discovered that the game was becoming too difficult for the casual puzzle audience we were targeting. The game play required intense thought. The players spent a lot of time thinking about the puzzles instead of interacting directly with the game. Completing the puzzle by trial and error was common for people who couldn't wrap their head around this mechanic. By contrast, other players really enjoyed the game play, as it required them to concentrate and think about each decision. But ultimately it was determined that this particular set of mechanics was veering too far from the casual feel we wanted (Sorry, Yavin!).

Also, once we played with this UI, we realized it took up too much screen real estate (and it was starting to look more like a business app instead of a game). We thought that we were likely to continue having UI issues if we pursued this mechanic.

We needed to scrap this set of prototypes and try something new. Our designer, Matt, has this to say about the experience of walking away from something we spent so many weeks developing: "It's discouraging to get feedback that indicates that you've been iterating in the wrong direction. But if we had not play tested those initial prototypes, then we would be in deep trouble right now."

Fifth Iteration

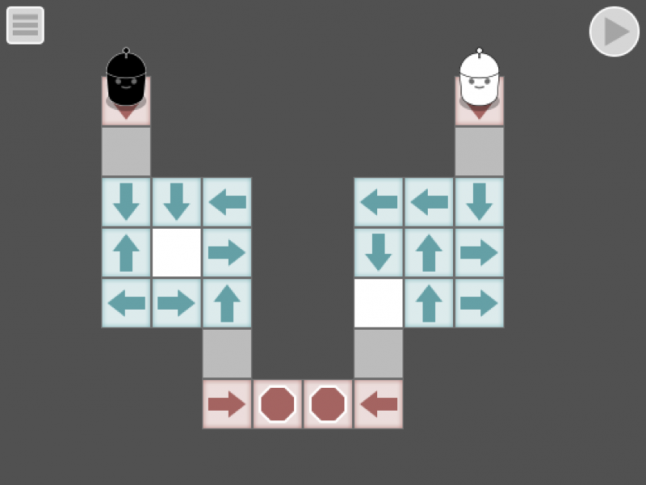

At this point, the designer decided to take the game play in a new direction: he simplified the path-creation mechanics. Instead of approaching this as a programming puzzle where you chained commands together, he instead focused on sliding the arrows to create a path. This approach made the game more tactile, because the player had something more tangible to interact with when solving the puzzle. With this mechanic, the player could slide an arrow onto any white tile and was blocked from placing an arrow on a gray tile.

He spent about a day testing his idea with a few more Photoshop Prototypes (and some internal testing). Once he had a good idea of how the mechanic worked, he wrote up a spec so that engineering could create a digital prototype. This prototype took 2 days to create.

This approach also solved the issue we had with our casual players: they grasped the mechanic more easily, and were quickly sliding tiles around to create paths. The designer created a few more puzzles and additional mechanics for the digital prototype in order to confirm that this mechanic was the winner, and further testing revealed that it was! We did additional friend-and-family testing and decided that this was definitely the direction we wanted to pursue.

Of course, while we have our core mechanic, we still continue to iterate on how to implement it into the game. For example, early on people expressed their intense dislike of the tight puzzles that only had one free tile to work with when solving the puzzle (ahem, see example above) and so we designed away from that over time. We still continue to tweak the game play with a lot of internal testing – iteration is something that continues up until you ship the game!

Lessons Learned

> Brainstorming and prototyping take time. This is a lesson that is learned on virtually every project, but given the rapidity of prototyping, and the small team size, the stakes felt much higher this time around.

> Stay focused on prototype goals. In our case, we were searching for a solid core mechanic that would work well on touch screens.

> Don't spend too much time polishing your prototype. If it's not working, ditch it and move on to something new. This is one of the harder aspects of prototyping, and can be a bitter pill to swallow.

>When the prototyping phase is done, the work doesn’t stop. You need to continue iterating on the mechanics as you add more complexity to the game play.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like