Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this excerpt from Game Design Secrets by Wagner James Au Randy Smith from Tiger Style (Spider: The Secret of Bryce Manor and Waking Mars) shares the story of how he and David Kalina built a successful mobile game studio building thoughtful, artful, genre-defying games for iOS.

In this excerpt from Game Design Secrets by Wagner James Au, Randy Smith from Tiger Style (Spider: The Secret of Bryce Manor and Waking Mars) shares the story of how he and David Kalina built a successful mobile game studio by adapting some of the core principles of great core game design and translating them to the iOS. In the process, they show how you can create thoughtful, artful, genre-defying games for Apple's platform and do quite well. The book is now available in paperback and e-book (use code "GDS12″ for a 40 percent discount at checkout).

In Spider, you play an arachnid, jumping and spinning your way through an empty mansion with the flick of your finger, discovering the mysteries of the family who once lived there along the way. As of mid-2012, the game has sold more than 360,000 copies and grossed more than $1,000,000. (Spider still earns more than $5,000 in a good month.)

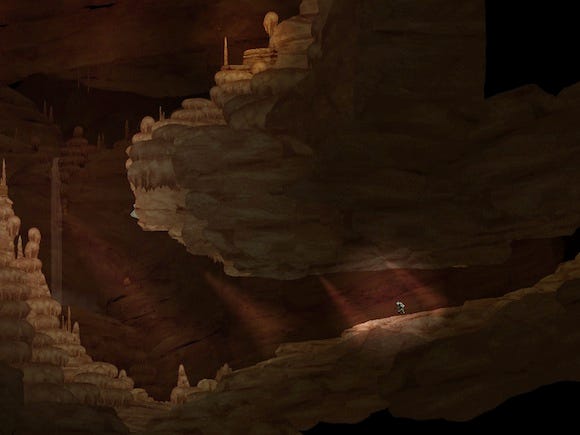

In Waking Mars, you play a lone, stranded space explorer with a jetpack, lost in the caverns of Mars recently discovered to be full of life -- specifically, a living, breathing ecosystem of alien life forms. Mars, which launched in March 2012, has so far sold over 55,000 copies, grossing more than $240,000.

"Both games have a long tail," Smith notes to me, referring to their small but steady sales months or even years after launch, "and as of this writing Waking Mars is still in the beginning of its sales lifetime."

The sales numbers are even more impressive when you consider how much these games took to produce: Smith estimates it cost $15,000 to develop Spider and $38,000 for Waking Mars. This is possible because Tiger Style doesn't really have an office or investors, and operates, as he puts it, with a business model that's "more like a film production company or a cooperative, perhaps."

Spider's $15,000 budget includes the purchase of all equipment, licenses, and legal support. It also includes $10,000 in royalty advances paid to the team. That sum, however, doesn't include any salaries or benefits. For example, during its eight months of development, Smith lived off of his own money.

"We're all essentially unpaid contractors during a project; then we all collect lifetime royalties when the game is released," says Smith. On top of that fact, consider that Tiger Style is a distributed company without an office; the company employees work over the internet, and the company doesn't have investors. That's about as low of an overhead as companies can get.

Waking Mars operated under the same model. It was a two-year development cycle that was supported by the income of Spider, according to Smith. They paid out $38,000 in advance royalties and about another $5,000 in other expenses. He and co-owner Kalina lived off the income from Spider during the two-year development of Waking Mars. (While they were developing Spider, they lived off their savings.) Now they're living off of Spider plus Waking Mars' income to develop their next projects.

"The rest of the team is more like a film production company," says Smith. "They are contractors who work with us when we have projects for them to work on and find other income the rest of the time. We provide royalty advances to those who need it during production."

Social media is an integral part to promoting Tiger Style's games. According to Smith, the trailers for both Spider and Waking Mars (posted to YouTube) were key instruments in selling the games to players who had heard of them but wanted to see more before spending their money. "We consider the trailer to be the single most important piece of promotion that we can do," says Smith. "We choose to show gameplay footage while also communicating the fantasy and story that was being offered."

For social network promotion, Spider had a feature that let you brag on Facebook that you were playing it or that you solved one of its quests. (The adoption rate of that feature was 11 percent.) Waking Mars did something similar, allowing you to Tweet to your friends back on Earth when you had completed research on one of the Martian species.

Fewer people Tweeted from Mars than Facebooked from Spider, which Smith attributes to implementation. "The Mars Tweets were also a bit more mysterious," says Smith. "Sharing with your friends that you just solved a mystery in a video game is probably an easier sell than posting something cryptic like [a Waking Mars Tweet] 'Larians prefer to eat mobile life forms but are also able to derive some nutritional value from Zoa seeds.'"

Smith points to several features in Tiger Style's games and the studio's development practices that have greatly helped sell more units, while keeping existing players engaged:

Updates: Spider had a very significant update called the Director's Cut that added 10 new levels for a total of 38. These new levels patched some holes in the story that players were confused about and contributed to fun new gameplay.

"The Director's Cut was such a significant update that it attracted new players, more attention, and some additional press," says Smith. "The iOS market likes to know that developers are listening to them and keeping their games updated and fresh. Updates also increase the chances of a promo spot in the App Store and draw attention from your existing install base."

Smith notes constant updates are a common feature in iOS games: "Some developers go so far as to release a game with only the bare bones that make it enjoyable, and then update continuously, targeting improvements and extensions to the aspects of the game that seem to satisfy players the most."

Playtesting: "For both Spider and Mars we did very extensive playtesting before shipping the games," continues Smith. "We really refined this process for Mars, having players focus on the iPad in front of them while the rest of the team was watching on a big screen.

"Fellow developers often had great insights, but the highest-quality data came from playtesters who were most like our target audience. Sometimes it was really depressing to watch these players get tripped up on designs that we thought made learning the game easy." (Casual gamers who were new to some of the deeper features Tiger Style was attempting.)

"We refined the opening levels of Spider and Mars over and over and over again until they were as tight and economic as possible while still easing casual players into an exciting, new experience. This all happened before we shipped the game, so we can never be sure how it impacted sales, but our guts tell us this emphasis on reaching the casual audience is one of the major contributors to our success on iOS."

Discrete Levels: Waking Mars originally featured a seamless world that would stream in as you explored. This made the caves seem vast and rambling and very believable. It soon became evident that the trade-off was player clarity. Players didn't know when one experience was starting and another was over. It was hard for them to tell if they were winning or losing; instead, they just kept stumbling forward into new things. Changing Waking Mars to have discrete levels that a player must finish one at a time helped with pacing and clarity. It also gave players the sense of accomplishment and an understanding of the game.

Leaderboards/Achievements: To provide more dimension to Spider, Tiger Style added leaderboards, achievements, and different game modes. "Waking Mars was a much larger game with more gameplay variety, so we felt those would be unnecessary additions," says Smith. "In retrospect we were probably wrong. Some players really got attached to the leaderboards, and most players had fun questing after the achievements. Without them, the game feels akin to a movie that you watch once. With them, the game feels more like a hobby that's worth coming back to."

As mentioned earlier, Tiger Style doesn't have a traditional office location, and all of its developers work remotely. "I don't think being a distributed company has impacted our final products, but it does change the processes we use to create and communicate design," says Smith. That involves the creation of highly detailed design documents, and the use of online collaborative tools.

As the creative director, one of Smith's most important jobs is to get everybody seeing the same end goal so that their efforts align nicely into a cohesive, unified work. Smith worked for years at game studios where people saw each other every day in the office, and talked often about the game they were designing.

You'd think that kind of direct, high-bandwidth communication would increase clarity, and to some extent it certainly does, but Smith also found that there's a tendency to take for granted that people understand each other when sometimes they don't.

"Comparatively, at Tiger Style," continues Smith, "I don't see everyone face to face, so I rarely assume they're picturing the same game I am. This puts pressure on me to provide effective direction. I find myself creating more evocative documents to communicate the vision and design."

When some problems can't be solved at the document level, Tiger Style turns to other solutions: "Sometimes things get tricky when we're attempting to solve a design problem, say something that's not working in the gameplay. Ideally, you'd like to converge on a whiteboard to sketch out your thoughts.

Editing diagrams collaboratively in real-time is a great way to brainstorm possible solutions. When that hasn't been available to us, we've at times just individually taken ownership over the problem for a few days until we can present a potential solution that's interactive and running in code. It's essentially like prototyping your answers instead of trying to talk through them. Again, it takes extra effort but is more likely to produce clarity."

As noted above, Randy Smith creates detailed design documents to clearly convey game concepts to his remote team. Here's some samples of those for Tiger Style's first game, Spider:

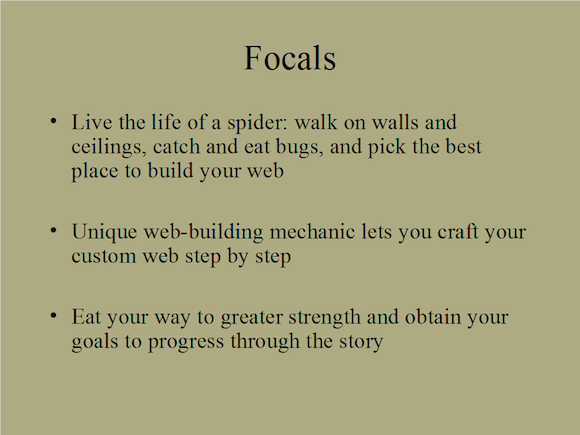

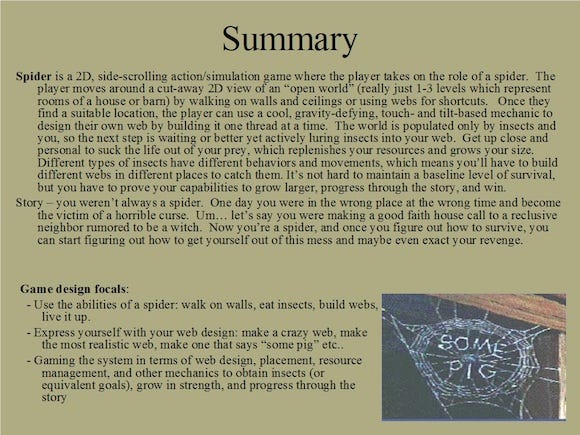

"This document is the 'treatment' of a brainstormed game concept," says Smith. "Its purpose was to develop a one-sentence idea into a potential game design that everyone could envision. This was written quickly, as we were considering several concepts simultaneously. It's important that you be able to boil the essence of your game down to a small number of very succinct bullet points." (See slide above.) "This helps you identify what is most important so you can focus on it to the exclusion of potential distractions and embellishments."

Click for larger version

"In this case, we already see right away that this document describes a different version of Spider than what we shipped." (See slide above.) "We started with this concept but let the software speak to us once digital prototyping began, evolving it into a more accessible casual game. There was never any need to redo this documentation, but if I had, the second bullet would probably read something about the core 'action drawing' mechanic and the third would reference the environmental storytelling that quietly invites players into the mystery of an abandoned mansion.

Click for larger version

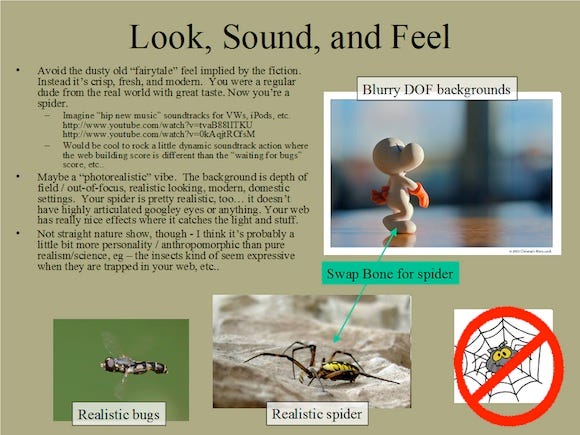

"On this slide [see above] I'm attempting to establish a tone that informed Spider: hip and realistic, not cartoony and goofy. In the end, we abandoned photo-real for an Edward Gorey-inspired illustrated art direction, but the tone set forth in this slide still helped to distinguish Spider."

Excerpted with permission from the publisher (Wiley) from "Game Design Secrets" by Wagner James Au, copyright © 2012.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like