Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A prototyping mindset is something that needs to be actively developed till it becomes ingrained. Knowing and applying prototyping techniques is an important part of the foundation, but that alone is not enough.

[ The original version of this post can be found in the articles section of my Vijay Talks Tech site. ]

I'm an engineer by training. Having worked on core systems most of my career, I have a strong tendency to choose the "right" solution over the "right now" solution almost every single time. This is a great trait for a software architect to have, since by definition, the main goal of architecture is the long term health of the systems being built. So, the trade-off is to choose the solution that is healthier for the long term rather than allow hacks in design or code. In reality, shortcuts are permitted, usually to respond to emergencies or for business / competitive reasons. But these hacks are recognized as short term fixes which are scheduled for replacement with more appropriate and viable long term solutions. This worked out very well for me when I ran the architecture team at Hotwire in one of my previous avatars, and there was naturally, a fair amount of tension between choosing designs and solutions that met the needs of the business but didn't damage the health of the product in the long term. This push-pull or tension is a good thing as long as the culture of the company is one that respects that compromise is necessary and understands that concrete mitigation must be put in place to replace hacks / shortcuts in a timely fashion. The engineering team at Hotwire was simply superb at this. They had a "maintenance queue" to which engineers were assigned on monthly rotation. The architecture manager (me) owned this maintenance queue. It was my responsibility to prioritize maintenance items and to devise a path to get those fixes into production.

The very trait of almost always picking right solutions over "right now" solutions proved to be a major handicap when it came to running a game development studio, but I learned a very important lesson in the process: A prototyping mindset is something that needs to be actively developed till it becomes ingrained. Knowing and applying prototyping techniques is an important part of the foundation, but that alone is not enough. So, here are some thoughts about how to develop a prototyping mindset.

A prototype is a design experiment, which can broadly be classified based on their intent as functional (explore an activity), visual (appearance) and user experience. Proof of concepts are slightly more complex design experiments that typically explore two or all three of the above aspects, but the same principles apply. Essentially, the goal is to learn something from the experiment, i.e. it answers some question, which dovetails nicely into the next part.

Yes, only one question; and it must be very specific. A question of quantitative nature is easier to answer than a qualitative one. A qualitative question would take some additional work post-creation of the prototype and is subject to biases. An example of a specific question in game development would be: "Does changing the variability of player attack dice rolls from 2d6 to 3d4 increase or reduce boss battle times?" This question is very specific. To answer the question, one parameter needs to be changed in the game, a number of (automated) tests need to be run to measure the variance in boss battle time and an analysis of the results needs to be performed.

It may seem a bit counter-intuitive initially, but if you find that yourself seeking multiple answers from a single prototype, then you need to break down the prototype into multiple phases till each phase answers exactly one specific question. Answer the question in each phase and then combine the information to answer the larger question. You may need to introduce additional phases to accommodate for effect of multiple changes on one another, but that does not alter the fundamental premise of answering one specific question at a time.

Prototyping needs to be cheap and fast. Not just cheap or fast, but both. You have to pick the right tools for the job and you must limit the scope of what you are prototyping. The way that I was able to get a handle on this aspect was to ask, "What question does this prototype answer?" This is a very different question from "What problem does the prototype solve?", which is the absolutely wrong question to ask. Prototypes don't solve problems. They answer questions about viability of a proposed solution.

Strategy is about doing the right thing. Tactics are about doing things correctly. Strategy is future oriented. Tactics are in the here and now. The strategy portion was (note: past tense) making the decision to create prototypes. The tactical portion is the correct utilization of the appropriate resources (tools, people, time, etc) to validate hypotheses. Strategy is over-arching and long term. Tactics are scope-limited and short term. Strategy produces goals, road maps and measurements to ensure that things stay on course. Tactics, in our case, quickly and efficiently validate hypotheses.

Prototypes are not the final product. They exist to validate (or invalidate) a solution you've come up with. They need to be good enough for that purpose. Do not waste time in spit and polish.

Prototypes are throwaway work. Once their purpose is fulfilled, they will probably never be seen / used again. So, limit the resources (time, money, effort) you put into them to what is needed to fulfill the goal of the prototype. No more, no less. Do not make the classic mistake of building your product on your prototype -- this is a well-trodden path to failure. You will most likely spend more time on the prototype thinking you can re-use parts of it for production and later find that the halfhearted compromises you made hobble the final product.

Prototypes reduce the risk of working on some feature or idea for an extended period of time, expending large sums of money, putting in a lot of effort, only to find out that it fails to meet targets and expectations. Have a clear goal for what you expect to get out of the prototype. What risk does it mitigate? What unknown dark corner does it shine a light on?

Try to use existing skills, tools, knowledge and other resources you have at your disposal. Do not conflate prototyping with learning a new skill or tool. It is best to spend whatever time is needed to acquire the skill, be it a new piece of software, a programming / scripting language or a project management methodology such as Scrum before you begin work on a prototype. There's no such thing as the perfect way to prototype. There are ways that work and ways that don't. As an example, I was told by developers at one company I worked at that Java was way faster for prototyping and iterating than C++. I proved them wrong multiple times, simply because I was considerably more familiar with C++ than I was (or they were) with Java. On that note, I've come to prefer Python (batteries included) for prototyping over these last few years. It was a skill I picked up explicitly for speeding up the iterative cycles when prototyping games. I also use it for production code these days as do companies like Google and Dropbox.

Any reasonably intelligent person already knows that s/he will be wrong more than right in unfamiliar situations. Prototyping is all about the world of the unknown and unfamiliar. So, don't forget this. It's perfectly fine to have your ideas and theories disproved many times over. Ultimately, you'll find one that is proven right. That's all you need. The cost of learning by doing via prototypes is orders of magnitude faster and cheaper than guessing wrong. You don't want to stare failure in the face after the fact.

Prototypes validate (or invalidate) ideas and theories. They don't solve problems. That's up to you. If done right, you already have a slew of potential solutions to the problem at hand. You build prototypes to quickly try out those solutions to determine which one(s), if any, actually will work for you in the real world.

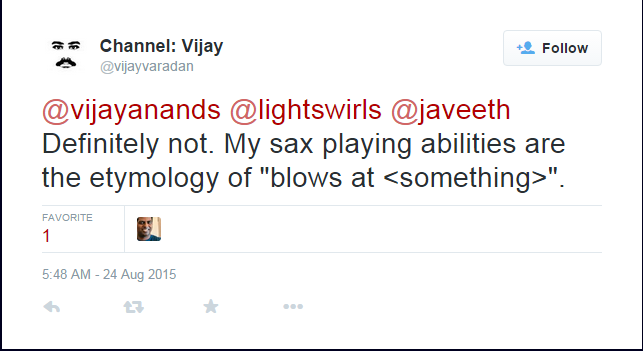

A few years ago, I started to learn how to play the saxophone. The early months are best described in this tweet:

Essentially, when you're start learning to play a musical instrument, no one, even your own mother, wants to hear you practice. So, you're free to make all sorts of mistakes and sound as off-key and abysmal as you please. Prototyping is a bit like that. A lot of your prototypes will simply not work. You won't put them on display for the world even to seek feedback. You'll mostly likely destroy them. And that's just part of the process. After practicing your musical skill for some time, you will try to show off you newfangled abilities. Showing off your prototype is a bit like that. Reception to it could vary wildly. But the feedback you get will be invaluable in making changes which in turn will lead to improvements in your final product. You final product is the equivalent of a public performance - you want it to be stellar. Your prototypes are all those private practice sessions and rehearsals with your close friends and family - prototyping is the journey, brickbats and bouquets included, of making your product successful.

You've figured out the purpose of your prototype, judiciously allocated resources and built your prototype. Some types of prototypes require you to show them to other people and solicit their opinions. It's important that you have the right attitude when you get feedback. Not all of it will be positive, nor should you expect it to be. When you do get positive feedback, accept it, analyze it and take it for what it's worth. When you get negative feedback, do the same thing. Set aside criticism that is not constructive, but do pay attention that which is constructive. Practice goes a long way in filtering noise from signal when you're hit with a barrage of opinions opposing your own or what you expect. It might help to keep in mind that it's not always easy to give negative feedback. Most people know it tends to usually be discarded and you might want to try and appreciate the effort taken by people who give your their honest opinion.

Please add any thoughts you have about developing a prototyping mindset in the comments. Thank you.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like