Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This post outlines an approach to game design that focuses on human values underpinning gameplay, and how to use them to craft meaningful conflict, fostering emergent storytelling.

There’s a lot of talk on narrative in games lately. Titans such as God of War and Red Dead Redemption 2 battle it out at The Game Awards while smaller titles like Life is Strange 2 push the envelope on other levels.

Most of mainstream titles bet big on authored, often scripted narrative; big emotional moments whose effectiveness rests on much the same tools like movies: script & direction, dialogue, performance. And looking at the impact these games have it’s hard to argue with results - that’s definitely one way of doing powerful narrative in video games.

However it’s not the only way. Games like Rimworld or Dwarf Fortress are often cited as those that offer “emergent narrative”, but while I’m a huge fan of both, I see them more as “anecdote generators”. They expertly offer fun, surprising, sometimes eerily impactful situations, but not really full stories, with intent and meaning behind them.

Today I’d like to share the mental toolset that I think contributes to content and mechanics in Frostpunk working towards a holistically meaningful experience. A “values-driven” game design approach if you will.

Frostpunk - a city building/survival game about society pushed to the limits, a title I led design for - was received very well. A lot of feedback post-launch emphasized the atmosphere, choices... and “story”. But Frostpunk is a strategy game. There’s no holywoodesque cutscenes, crisp dialogue; in fact, there’s not a single NPC in the game. And yet the overall chain of events often led to players perceiving it as a coherent tale that they co-authored.

So lets take a step back - what really is “story”? Each guru offers his own definition, but there’s one particularly interesting notion among the works of Robert McKee, the author of Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting.

He asserts that story is a way for people to make sense of the world. And each story, at its heart, is about a conflict of human values. Life vs. death. Victory vs. defeat. Love vs. hate. There’s as many values as there are ways to describe the human condition (which is why all stories often seem to be the same, yet manage to stay fresh). And meaning arises from the way value reversals are delivered through the structure of the story - from beat, to scene, to act.

What a happy coincidence that we’re very good at doing conflict in games! It’s at the heart of every gaming experience, whether it’s “How do I get to understand what’s going on” in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture or “How do I not die here” of Dark Souls.

But if you look close enough, it turns out that conflict in games is really about human values too! It is, however, often pretty trite.

Life vs. death; victory vs. defeat - these are the core conflicts of most games made today. Of course, there are exceptions; unusual, quirky, unobvious themes. And frankly, there’s nothing wrong with this particular set of values. There are, and can be, powerful stories weaved around them. It’s just that they are extremely overused in games today.

Simply knowing the values your game is about is not good enough though - after all, what’s the practical takeaway here? Thankfully, we can look more in-depth into how games are put together and see whether it gives us something more to go by.

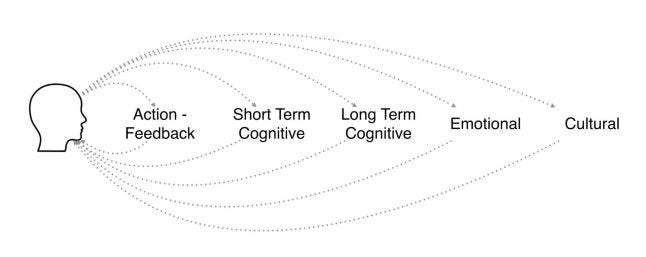

From a design standpoint, just like stories are made of acts, which are made of sequences, which are made of scenes, which are made of beats, so too games have a structure. There’s the shortest, action-feedback loop. Then there’s short-term cognitive (“tactical”) and long-term cognitive (“strategic”) loops. Further out are emotional and cultural loops, which reach into the way the game is perceived by the player and the larger pop-culture.

Michael Sellers proposed this loop structure in his excellent book Advanced Game Design: A Systems Approach.

The trick with value conflict is that it doesn't just play out through the theme of the game or its more or less scripted narrative; it operates on each and every structural level. In traditional stories, scenes are driven by value reversals delivered in beats. So too every loop level really is about a particular set of values (even if they are all life vs. death) and a gameplay conflict they underpin, which the player is trying to resolve in his/her favor.

Lets take a look at how it looks in Frostpunk.

Loop level | Conflict of values |

|---|---|

Reflective Loop (emotional & cultural) | What does crossing the line mean? |

Long Term Cognitive Loop (strategic) | Crossing the line vs. keeping to your morals |

Short Term Cognitive Loop (tactical) | Extortion vs. balance Compassion vs. Efficiency |

Action Feedback (visceral) | Good of one vs. good of the many |

At the lowest level the game is about gathering resources - you employ people at various places and they procure the stuff city needs to survive. It’s a pretty standard conflict of having vs. not having but thanks to the survival aspect of gameplay it can have other meanings too. For instance: will you send children to work? Will you send them to work in coal mines? In the freezing cold? It can become a conflict of compassion vs. efficiency on the tactical level which is much more interesting and fresh.

Higher, up we have the short and long term cognitive loops, the tactics and strategy of survival. Tactics largely rest on how you utilize the various buildings and abilities you unlocked and how you deal with limitations of your chosen build. This always has an effect on the people of your city: you can ruthlessly overwork them to get what you need or you may choose a more careful, compassionate approach which is much more risky and difficult, especially when going blind into a scenario.

The strategy layer loop is reflected most in one particular part of the game (aside from the tech tree and the build order you choose): the Book of Laws. It’s a set of choices that shape the rules for your people, enabling various behaviors, buildings, abilities that can influence your situation drastically. For instance: if hope becomes a problem, will you print propaganda? Will you enable your guards to disband protests against your rule? “Will you cross the line” was the central theme / value set that permeated this part of the game.

Book of Laws was created to support medium to long term planning, enabling tactical and strategic gameplay on unobvious values such as honesty vs. lies (possibly "in good faith").

The loop level that was unresolved for the longest period of time in development was the reflective layer (a term which I use to aggregate emotional and cultural loops - the “meaningfulness” of the game). Frostpunk was different to This War of Mine, our previous title, in that it was difficult to empathize with 500 people. Pure emotion was harder to come by in a much more abstract, calculating genre of survival/city-building. And yet there was hope: while playtests showed that players not always empathize with the citizens - they are a statistic - their whole playthrough and what they did to survive promoted a post-playthrough reflection - “Did I really do that? This is how totalitarian regimes are born!”. And there was clearly some discussion whether the question has merit - which to me it means it does.

Of course, the table above doesn't do justice to the 3 years of iteration it took to arrive at such a structure. The description here is pretty high-level, for the sake of clarity. But if we looked close enough, the vast majority of choices, mechanics and content in Frostpunk can be labeled with the value conflict they enable - we just made sure that all of them stay in line with the overarching themes for different loop layers, and the whole game.

Such a systemic view will never replace the role of intuition, feeling, authorial intent and all of the soft aspects of game design, and by no means is it equally practical for all types of games. But, in the end, all games are about human values, whether they’re consciously designed or they “just happened”.

I find this approach useful both in establishing how the high concept translates to different layers of the game and in maintaining true north when getting down & dirty with the low level. It helps me be more conscious about the meaning that emerges from the mechanics and therefore enables me to actually *design*, not just eyeball it. I believe that this can be very useful in crafting games that foster “emergent narrative” - the stories that players tell through their actions within the possibility space the game enables.

Today often these stories are pretty flat - players either live or die, win or loose. But enough fidelity, freshness and uniqueness in the values the mechanics and content operates on - and maybe over time the emergent stories will grow into something truly profound.

Thanks to Marta Fijak (@YerisTR) for all the work we did on the subject. If you want to chat, you can reach me on Twitter (@qoubah)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like