Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Some thoughts about Bloodborne, notably how it eliminates passivity thanks to its gun mechanics. A bit of reverse-engineering might be useful to better identify their function and guess how they were conceived...

This article was previously published on my blog, at this address: robin-v.net/hunters-pistol/

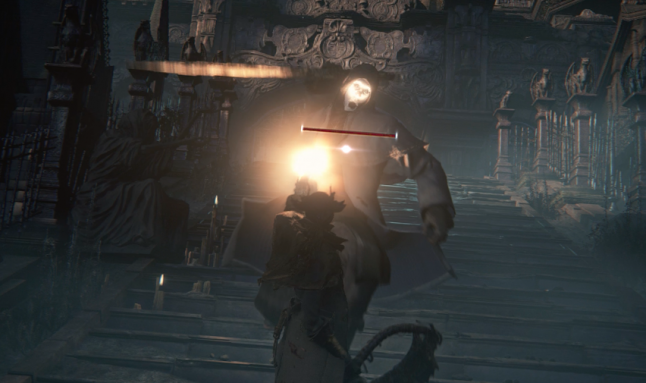

I finished Bloodborne two days ago, and very much liked it. It's an interesting game in many ways, some of which I've been wanting to write about since I started playing. I'll eventually talk about the story – I'll let you know when I start venturing into spoiler territory, in case you haven't finished it yet. Before that, though, I'd like to have a look at the game's most advertised new feature, its main differentiator when compared to its predecessors: the gun mechanic.

When you start the game, you're given two and half tools for killing: one fairly large cold weapon that has two equally murderous forms (you can usually trade swiftness for reach and/or brutality) and a firearm. When it was revealed that this shooty, noisy device would go into the protagonist's left hand instead of the expected shield, many players were surprised, worried even; I know I was. The safety provided by holding down the left trigger to hide behind your shield in Dark Souls (the previous game from Bloodborne's developers) allowed for a slower, more measured play style, and that was exactly what I loved about it. Bloodborne, on the other hand, seemed to be all about constant side-stepping and frantic shooting – twitchy, nerve-racking, focused on precise timing, and indeed without a moment to rest. There is a shield you can equip in Bloodborne, but its in-game description reads like a design note from director Hidetaka Miyazaki, directly addressed to the player: "Hunters do not normally employ shields, ineffectual against the strength of the beasts as they tend to be. Shields are nice, but not if they engender passivity."

What's interesting about this note is how it almost explicitly reveals why guns have replaced shields in Bloodborne. The developers felt there was a problem with Dark Souls that they needed to fix – passivity – and the firearms were their solution. Let's fictionally go back in time and pretend we're attending the early design meetings for Bloodborne... it probably went something like this. The starting point was the removal of the shields; that much is obvious. However, shields did come with a mechanic that didn't encourage passivity at all: parrying. To parry in Dark Souls, you opt not to keep your shield up, and instead try to raise it right when an attack is about to hit your character; it's risky (half a second too late and the attack does hit) but if done successfully, it staggers the enemy, leaving them vulnerable to a powerful riposte. That's the kind of gameplay mechanic that requires so much focus and concentration that you can usually feel it affecting your whole forearms, as they tense up waiting for the exact right moment to press that button. It's anything but passive. How, then, do you keep it without the shields? What kind of combat-oriented tool could complement a main weapon and allow instantaneous parrying, but not passive protection?

The answer's definitely not 'guns'. Daggers, maybe, or some sort of steel gauntlet... but not guns. That doesn't matter, though; let's call this mysterious parrying device the Tool X for now.

Meanwhile, in a different meeting room, here's what designers are struggling with: bows. Dark Souls featured bows which you could aim freely; as a result, players would find spots in the game's level from where they could shoot arrows at unexpecting enemies. Videogames being what they are – simulations that rely entirely on flawed programming – if the player's character was far enough, said enemies would fail to register their existence at all, despite having just received an arrow in the chest. Players took advantage of this and defeated monsters meant to be extremely challenging opponents, simply by standing just far enough and shooting hundreds of arrows at them. In other words: they found a way to beat the game while staying passive. Obviously, this would not do.

Bows, then, also had to go. Just like shields, though, they did have their usefulness: especially when facing another player, the possibility of them taking out a bow kept you on your toes, even at long range. Finding an alternative that avoided the aforementioned pitfalls seems easy enough: you need a certain Tool Y that can hit from a distance, but not too far.

Let's recap. Tool X is very useful, but it's only used in one very specific situation: in close quarters combat, when an enemy is about to attack. Tool Y is also very useful, and it's also used in only one context: when engaged in combat against a foe that's out of range of the main weapon. The genius of Bloodborne's designers is that, looking at these two absolutely unrelated issues, they realised that Tool X and Tool Y could be one and the same, since their usage didn't overlap. There would be no circumstance under which both would be needed simultaneously; which meant they could be grouped under one label, associated to a single input from the player. The question then becomes: what can hit foes from a distance, is quick to operate, can stagger a vulnerable enemy, and provides impactful feedback when doing so? A gun. That's why I love the mechanic: in the context of Bloodborne, it makes perfect sense. It elegantly solves many issues at once, and efficiently communicates with the player: the weapon's booming noise suddenly becomes invaluable when you're in the middle of a tense face-off against a boss. Each press of the trigger results in a loud bang that supersedes every other piece of information generated by the game, to reach the player's senses through a high-priority lane; if that shot also happens to be a successful parry, the gun's noise is accompanied by an even louder, heavier audio cue. As a player, you learn to identify those sounds, to the point where the appropriate reaction almost becomes a reflex – which is exactly what Bloodborne, with its unrelenting hostility and difficulty, demands of you.

And in the same way that the game requires intense focus and accepts nothing short of perfect timings, it itself shows incredible focus and perfectionism. The same philosophy that probably led to the firearms can be found in all of its mechanics, in an incessant bid to eliminate passivity: most notably, the 'rally' feature, which allows a player to regain some of health lost after being hit by immediately hitting back. When, in previous games, you would retreat (or hide behind a shield), wait for a safe moment, then drink a potion, here the best strategy is often to strike back right away – although, as you can imagine, that exposes you to more attacks, more risks. Again, the stakes are raised, the tension is cranked up a notch. What I find even more interesting, though, is the more subtle side-effect of the main weapon's transforming abilities. As I said earlier, it can switch between two forms – one meant for quick and agile movements, and the other one for more heavy-hitting blows. (It's worth noting that one also bridges the gap between close quarters and long range: between the cold weapon's two forms and the gun, there's always one tool to hit an adversary, no matter where they stand in relation to the character.) There are three primordial aspects to the transformation process: it only takes a single button press, it looks cool, and it can be done while the character's moving. Combined, these characteristics mean that most players probably keep pressing that transformation button for no particular reason other than to keep their fingers busy; the effect is satisfying and comes with no penalty. And just like that, even in the mundane act of traversing an empty level, passivity is vanquished.

If anything, Bloodborne's too focused. (If you don't want to know anything about the story, avert your eyes now!) By the end of it, I was growing bored of its insistence on exploring increasingly dark, morbid, gruesome themes; not once did it stray from its initial stance. It only kept on diving deeper and deeper into madness and horror, evoking Lovecraft's works more and more – to the point where it seemed like Yharnam was From Software's interpretation of Arkham. That's my one complaint with the game: where Dark Souls kept a constant hint of wondrousness in its tone and settings, and could surprise you at any moment with majestic landscapes and the nagging sense that you were an intruder upsetting a melancholic harmony, Bloodborne lets you know from the get-go that there will be no respite. It can be hard to keep on slashing your way through endless frenzied beasts, when you know that more gore awaits beyond the next door, that the next environment will be yet another bleak delirium.

And still, you do persist, because you know persistence and stringency is what it's all about. Bloodborne presents a story, but it doesn't force it upon you – far from it. It asks you to get it yourself. It merely complies with your inputs, as a neutral performer; press O, and your character rolls to the side. That roll is always the same: it takes a very specifically tuned time to be executed, makes your character travel by a very precise distance. Shoot at the exact right time, and your enemy's animation is instantly interrupted, leaving them vulnerable for a definite amount of microseconds. Perform a counter-attack: see the counter-attack animation play out. Always the same. Contrast that with the videogame incarnation of Batman, for instance: a single button never does the same thing. Press it repeatedly, and the character jumps in all directions, throwing kicks randomly selected by the game from the pool of possible kicking moves; if the conditions are met, Batman uses the décor to beat down criminals, pushing them through windows or throwing them against walls. If you successfully trigger that game's counter-attack equivalent, you never see the same animation: Batman may dodge to the left, or he may jump above his enemy, or he may block a blow with his arm. Only the result is the same (the attacker's knocked out). Batman's game (like countless others) interprets the player's inputs to create a choreography, but it comes at the cost of precision and player-driven behaviour; it is spectacle, and the player's the audience. Bloodborne rejects that notion by leaving all of the character's actions entirely up to the player, without any filter to smooth them out or make them prettier: any behind-the-scenes processing would take away from the feeling of accomplishment. 'Rigour', Bloodborne seems to be hammering home. 'Strictness'. As you realise that the game expects you to adopt its austerity for yourself, it all becomes clear, and you embrace the authors' crusade against passivity.

And as you contemplate how deep into darkness you still have to go, one thing does become clear as day: giving up would be quite a passive option, wouldn't it?

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like