Back in August, Schell Games decided to take a risk: they halted production of all their projects and let their 70 employees, myself included, work on whatever they wanted for a week. Awesome stuff was created, and the studio managed to allocate some resources to continue development on one of the resulting games. Three months later, that project is out on the market.

The game in question is InnerCube. Six people developed a strong foundation over the first week, then five of us worked on getting it ready for release over the next three months. Here is what I learned from the process:

It's amazing what a focused team can accomplish in a week

I knew this from way back in grad school, but it's a completely different matter when the people involved are experienced devs. When you have the tools, the talent, a gameplan and the motivation, you can create something completely playable in a week.

The InnerCube (back then called Color Cube) team knew what they wanted their core mechanic to be and focused on developing the art, sound and gameplay over the week. At the end they had a completely playable, 10-level game.

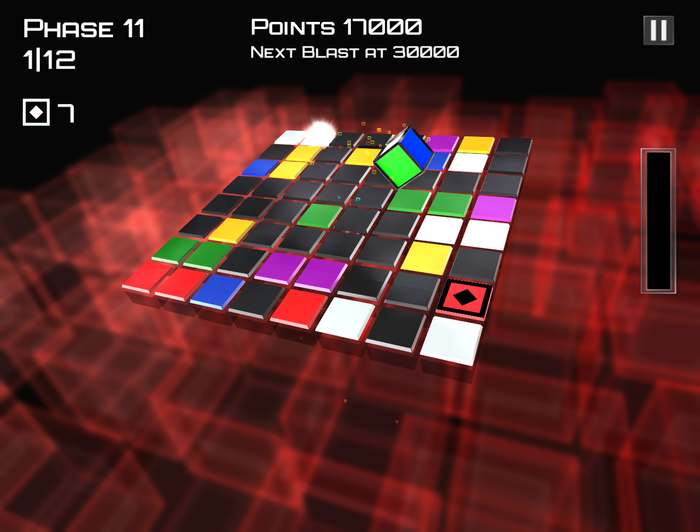

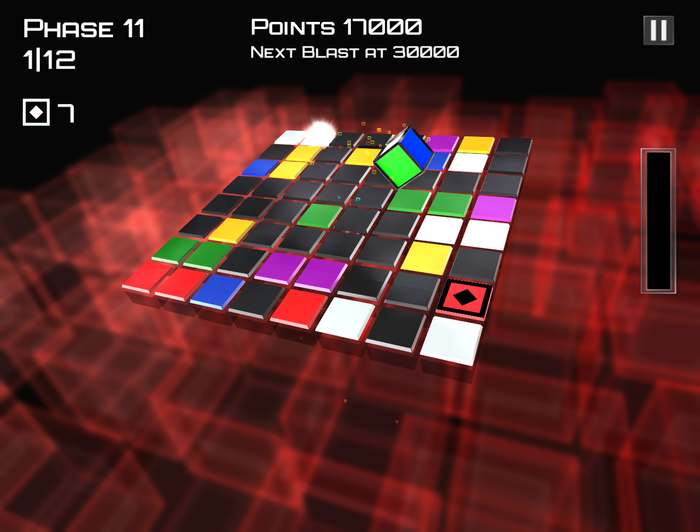

InnerCube gameplay

Once the game is running, Agile works wonderfullyFive of us at the studio just happened to be wrapping up a different project, so management decided to let us work on InnerCube while they figured out which other project needed our help the most. The plan was to re-evaluate project needs at the end of every three-week sprint, so we were tasked with working on IC in such a way that at the end of every sprint we had a potentially shippable game. This did wonders for the dev process, forcing us to prioritize features in three-week chunks and setting up a great rhythm for playtesting. Two sprints later, we had a completely different game: same core mechanic but entirely new gameplay. After two and a half months, we were ready to start submitting final versions of the game to portals and festivals. And at the end of every sprint, we had a fully-playable build.The power of a strong core mechanicThe initial game that came out as a result of Jam Week had an amazing core mechanic - in fact it was so good that Design felt that we could be doing a lot more with it. We designed two new gameplay modes and organized both internal and external playtests where we had players give each mode a try. Lo and behold, playtesters chose the two new modes over the original one.Having a strong core mechanic was a blessing all through our dev process. In fact, it was the reason that we could get the game out so fast, since the main interaction was already designed and programmed at the end of Jam Week.

Game Modes

People love feeling smartPlaytesters feel instantly challenged when they pick up IC for the first time, and feel smart about completing puzzles even if it took them way longer than average and an exorbitant amount of moves to do so. Why? Well, IC puzzle levels don't have a fail state, so even if it takes you an hour you can still figure them out. Secondly, they are reminiscent of both a Rubik's Cube and spatial puzzles found in IQ tests, so once people DO figure a level out, they associate that success with completing an IQ challenge.On top of this, each level has three challenge tiers: completion (beat the level), excellence (get a low number of moves) and perfection (get the minimum number of moves). The game makes you feel smart and remains challenging even for the smartest players.Your mind works in mysterious waysThis has nothing to do with the process and everything to do with Game Design. If you've played IC then you know that it's all about getting the hang of the cube's movement. I'm typically terrible at 3D/spatial puzzles, yet after designing levels for a couple of days I found myself getting a frighteningly firm grasp of the cube's motion range and patterns. I developed a scary intuition for determining which captures were easy, hard or impossible from any given location. I became an IC freak.And I still am. I can kick anyone's ass in Survival mode (makes sense, since I designed a big part of it) even with my history of atrocious spatial awareness. It's the same feeling as when you find yourself playing flawlessly through a Rock Band song without really thinking about it, your hand on autopilot. It ties back to the previous point, about people feeling smart: one tester voiced it perfectly when he said that he found himself capturing tiles with the blind side of the cube (the faces hidden by the camera angle) even though he couldn't conciously pinpoint what color should have been on that face. It's scary but it makes you feel good.Employer trust builds employee moraleI'll wrap it up with the unavoidable self-advertisement. At Schell Games we specialize in a sector of the market, and it's pretty freaking awesome for management to let us work on any project (and any genre) we want for a week, on their dime. They took a gamble and, as far as I can tell, it paid up in terms of employee morale. Hopefully also in dollars earned, if not with IC then with some other project in the future.You can give InnerCube a whirl for free HERE.Full Disclosure: I work at Schell Games and was one of the Game Designers on InnerCube.