Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

After playing through the 3Ds rerelease of Majora's Mask, it struck me how emotional Nintendo made the experience of failure, and how unemotional other games have made it. I explore the mechanics surrounding failure, and what this means for the industry.

Majora's Mask, by any reading is an incredibly sad game. Whether you read it as stages of Link's own death playing out in his failing mind, or as Skull Kid's lonely attempt at apocalyptic terrorism, every nook and cranny of the game is very obviously filled with characters grappling with loss and death (sometimes even their own!). There are other games that have explored very similar themes, but Majora's Mask, through a mechanical set-up that facilitates its theme, elicited a greater range of emotions from me than many other (ostensibly more dramatic) games. Darksiders may have been about the end of humanity, but it didn't care about humanity's loss. Heavy Rain may have made me sad about the loss of a son, but it didn't let me miss him. Dante's Inferno may have had me confronting the mournful souls of the dead, but it didn't let me mourn. These games all fail at failure, and looking at their examples, in contrast to games that have done it right, can help us to design games to be as dramatic as their linear counterparts on paper, stage, and cinema.

Firstly, you dear reader, may have problems with the original premise that games don't make failure emotional. One emotion players frequently experience is frustration at failure. It's true, frustration is an emotion worth pursuing, and the overcoming of frustration by working hard teaches valuable lessons, and is in fact quite a lot of fun. Anger is a legitimate emotional response to loss, and joy is a legitimate response to overcoming frustration. But it is only one of a slew of emotions.

The original source of games designing to trivialize death is the psychology and economics of arcades. The arcade player only pays you, the designer, when they they had a short run (and so have to put their quarters in in rapid succession), got very close to success, failed, (and this is the important part) aren't scared away by that failure.

![]()

Now, death is a terriying kind of failure, and if failure in the game meant players actually died in real life, well that is an extreme, and they wouldn't be playing a game anymore. But even when the loss is less, say if player failure means they respawn in an entirely different world where all the physics are different and their knowledge from the previous playthrough is lost, players would still avoid playing, since there is no way to learn their way out of failure. Designers who made games that scared players away were out of a job. Henceforth, we have the invention of lives, heath bars, respawning, and so many other inaccurate and trivializing mechanics. Even today, when the visual ability for designers to express themselves is less hamstrung and ostensibly we should be able to design for the whole spectrum of human emotion, conventions to postpone and minimalize failure are used without designers understanding the implications of their checkpoints and save mechanics and other such safety nets.

Film does not have a safety net. Music does not have a safety net. It is easier in passive mediums to finish a work than to not finish a work. Literature might be more akin to games in that the audience must actively work to finish the reading, but it comes nowhere near the effort needed in games.

Most player's don't finish games. There is a pretty popular GDC talk from last year, written about at IGN. As reported, Steam's library recorded players' game progress, and in the end it wasn't so much a question of what games player's couldn't finish, but what games player's could. Only 66% of people finished Walking Dead: Season 1: Episode 1, and that was the most-finished game of their survey. Walking Dead's own last episode, the finale of the season only had 39% of players finishing. Could you imagine not seeing the finale of a show you'd paid money to watch? Here, books are a great comparison. People have trouble finishing books too... some books. As a nifty Goodreads infographic shows, people don't finish books for one of the same reasons they don't finish games: a lack of engaging material, an excess of frustration, or the expectation that it won't get better later. I'd like to suggest that these are reasons why people leave games behind, but I'd also like to suggest that another reason is that players aare satisfied with endings the designer didn't plan for. Stick with me and we'll get back to Majora's Mask soon enough.

When thinking about failure mechanically, from the designer's perspective the only true failure a player can have is not finishing a game. Every other failure is merely an obstacle between the player and a designer's ideal end. Dying may send us back, but never so much that we can't recover that ground in the remainder of our play session. Many designers think in terms of literature when they tell stories, doing their best to manage a balance between streamlining the play experience to be easy enough to eventually finish, and challenging and incentivising players to get engaged with the characters, story, and design mentality. They have an end in mind if they're making a storytelling game, and they consider themselves successful is they can guide players there.

Some games like to focus on emergent play and systemic storytelling. Such is the way of Civilization as well as most fighting games. The story comes from the players struggle with the game or with other players. But these games are much more focused on the player than the more directed narrative. It is really hard to follow the story of an NPC when they are one face in a swirling system of faces.

Eiji Aonuma chose to make Majora's Mask a Non-linear story, but because of the limitations of the N64, the team could not implement enough interlocking systems to make the world seem emergently real, yet thy were still successful in building a tragically living world. I was engaged enough that I beat Majora as a child, and I've picked it up as an adult to see if it would be as engaging again. I haven't beaten it yet, but I'm on track to much faster than any other game I've played recently.

Let's look at some elements that fundamentally contribute to Majora's success. The cyclical 3 days are a great example. In fact, it is both the backbone to the player's story and to every other character in the game. Termina has a schedule for its last 3 days, and you as a player can only see so much of it. The mystery of the world combined with the known schedules of characters you've run into is the air that breathes life into the game. It is also the schedule which turns your choices of what to do when into tragic failures and the pain of abandonment.

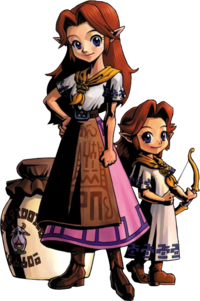

Schedules, you say? How can schedules be envigorating? Well, instead of an explanation here's an anecdote. Romani ranch is a milk farm you discover abou halfway through the game, and there, fenced in, is your horse who was stolen from you at the beginning of the game. Romani, the girl named after her ranch, is holding the horse and will give it back to you only if you show up at two in the morning to help her out with something. The game here is teaching the player about setting alarms, and I dutifully placed a reminder in my notebook. Once you show up on time at night, aliens show up to raid the farm of cows, you shoot them down for two minutes with the farm girl cheering you on, and then you ride off with your horse on to the rest of your adventure.

Later on in the game, having reset the cycle of 3 days, I was in a dungeon solving puzzles when the alarm I had totally forgotten about went off, and I remembered the thrilling standoff against the alien invasion and thought the barn must have been raided. When I got out of the dungeon, I rushed back to the farm, to see how it looked without any cows, and unsurprisingly found totally empty pastures. In the barn, though, I found the older sister of the farm girl crying in the corner. Apparently, without my help, the little girl had tried to fed off the alien invasion and had been abducted herself. I was actually appalled. I was fond of the little girl. She was spunky. She named me Grasshopper because of my green clothing and the way I ran everywhere. The genius of Majora is, continuing on with my adventure, I still had that alarm, and every time it went off, and my fairy took my attention away to ask me, "Hey, wasn't there something you were supposed to be doing about now?" a picture of Romani getting carried away from her namesake farm and the sister who loves her.

I had failed her. It was frustrating, sure, but more than that it was really sad. All the characters in the game are in some plight, and the adventure only ends after many many cycles of their pain, when Link finally saves the Skull Kid from his own personal hell.

I don't know a lot of games that have made me that truly mournful. I have grieved very few virtual characters. But every game where I have had those genuine deep feelings I have finished, fervently, like a good pageturner. I am sure that if gaming ever has a problem with engaging an audience other than teenage boys, it will be in no small part because of our trivialization of death, and our failure to embrace failure as legitimate.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like