Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Though it may seem self-evident, rapid iteration is a great tool for creation small games, and Mobile Pie's Will Luton discusses how his team made iPhone title B-Boy Brawl iteratively, after initial failure through too much rigidity

In this article I'll discuss a game creation method through iteration for small, unique projects, and will describe how the failures and success of the process of designing our studio Mobile Pie's upcoming iPhone and iPod touch title B-Boy Brawl: Breakin' Fingers shaped that methodology.

I will discuss our initial design approach, based in the traditions of linear video game design, and how that evolved, through the failures we saw and the confusion we felt, to produce a core gameplay mechanic that is fun and functional and how the process can be refined and applied elsewhere successfully.

I will consider video game design according to Ian Bogost's theory of Unit Operations; this suggests video games are constructed from discreet unit operations which function to create a system which delivers a desired meaning. We can hypothesize that our approach to building a complete system, or video game, must be based on a sound understanding of how these unit operations function with each other to achieve a desirable outcome.

Existing systems can be deconstructed and recreated verbatim or slightly deviated, with reasonable ease and security. However, if we wish to construct a new system, relatively unique from those that already exist, then we must choose the correct unit operations (or design elements, perhaps) which interact to create our desired outcome, however their selection is tricky and cannot always be deduced by pure logic.

Instead I suggest one must create, test and refine a unique system through an iterative developmental process; observing the feedback of the system, isolating the elements that pervert the intended meaning, replacing them with those deemed more suitable and repeating the process until a satisfactory result is observed.

The proposed process may seem self-evident to many seasoned video game design practitioners, especially those with experience of Agile methodologies, however, best practice at each stage and considerations for different projects are discussed throughout, with conclusions drawn from our own successes and failures.

Digital content delivery has long been the prophesied savior for an industry creatively bound by huge overheads and a physical retail stranglehold. While concept approval and overzealous development hardware restrictions may hinder certain console outlets, the PC and Apple's App Store both allow small development teams the freedom to test the water with commercial yet ambitious and unique games, providing for interesting experiences such as Zen Bound and World of Goo, as well as thousands of miserable, ugly failures.

As video game production costs grow and return becomes increasingly spread, ever more financial risk is put on all new development. In order to normalize the market, publishers, as well as studios, greenlight fewer products with unproven design elements; focus has shifted from design innovation to proven success and careful market positioning, slowly homogenizing the video game experience and potentially eroding consumer confidence.

The huge budgets and slimmer margins have also brought with it a culture of tight micro-management: both in terms of scheduling and over-reliance on meticulously pre-planned design, which incorporates the marketing will of licensing and small risk-free design deviations; both of these blights are linked creatively as well as commercially.

Although this may well be an understandable and, perhaps, forgivable norm for the large publicly held companies, small indie developers are gaining worldwide notoriety by releasing attention-grabbing games which deviate massively from the slew of cookie cutter commercial titles. However, for every Darwina or Alien Hominid there are a thousand nice ideas poorly realized that ultimately sink and disappear without even a ripple.

These failures could in part be blamed on development methodology; placing too much faith in the big studio ideology of immovable production paths. In taking a great idea and committing, what might seems sensibly, to the design very early on small teams can, from my experience here at Mobile Pie, put themselves in a perilous position where predetermined schedule is chased at the cost of quality.

The Iterative Design Development methodology was born from the evolution of the design process required to produce B-Boy Brawl: Breaking Fingers.

B-Boy Brawl was inspired by a series of YouTube videos in which people were using their fingers as arms and legs, to recreate break dance moves on a small scale. Initially the aim was to teach people how to reproduce the moves, but as we discussed the concept, goals were introduced and the product became a game.

Through these early discussions we decided the game was to uphold some very specific design ideals:

Teach the moves. For the user to learn and remember each unique move.

Theatrical gameplay. For the game to be fun for non-users to watch.

Accessible. For a user to easily pick up and begin playing, with little instruction.

Adaptable. Allow the user the freedom to perform the same move in different ways.

These ideals were undocumented, but existed as aims for the project and became immovable, fixed necessities. Although we approached the project with the idea of organic development these ideals restrained and shaped the design in an unexpected and unwanted way; we had inadvertently fixed design, and thus a development path.

Through development some of these ideals proved to be in direct conflict with one another in both obvious and obscure ways. On the surface we may see that accessibility is at conflict with the user having to learn moves. However, much deeper conflicts exist between both of these ideals and adaptability. A comparatively non-prescriptive mechanic may seem desirable to increase accessibility, but in fact the opposite was proven true, as during testing it became obvious users required more firm direction.

Initially, I documented two prototype concepts: one which featured buttons indicating where the user's fingers should be placed, and decreasing circles to indicate timing, and another which featured a HUD displaying the beat and the present, past and upcoming moves.

Mocked shots of the two proposed prototypes, representing a button-orientated and a HUD-led design.

From simply looking at these prototype proposals, we made assumptions on how the user would interact with both. It was considered that having buttons would make the game too prescriptive and monotonous, destroying ideals of theatricality and adaptability.

More important, however, was what we did not consider: How effective each approach would be at serving the required information to the user and how they would interpret it. We were blinded by what we thought the user would want and so did not consider what the user could use.

We fixed the design through discussion and documentation and built an initial prototype of the game, where there existed two bars as the sole direction and feedback for the user: one indicating the beat, and one indicating the moves. Upon playing it the team was very happy with the results of their labor. The game played as we had envisioned and planned it, and we felt assured that, despite it being a little rough in its present state, people would enjoy it.

An early build of B-Boy Brawl running in landscape with the move and rhythm bar.

We immediately gave the prototype to our peers for review; we knew what we had was not perfect, but we certainly did not feel it was fundamentally flawed. Watching people play it -- or fail to play it -- came as a great shock. At this stage there existed an obvious disparity between the team playing it comfortably and enjoying it and the inability of our users to even grasp the basics.

The team had between us designed and implemented the entire system, and so had an intrinsic understanding of its functions; the way and form in which the information is presented, what the information represents, and how it should be interpreted to perform the correct actions and bring about an enjoyable experience. In linguistic terms, we were the ideal speaker-hearer, understanding without exception the meaning of the language -- in this instance a video game interface -- which we had created.

The feedback we received from our test audience was varied and occasionally conflicting; some blamed themselves for failing to understand the gameplay, others claimed tweaks should be made to the tutorial, that the music tempo should be slower, that failure conditions should be less stringent, that they didn't know where to place their fingers next, or that the beat should be better visualized.

We took the feedback from the test subjects on board -- both their verbal feedback, and that which we observed from their actions during play. We built a new prototype, still restrained within the ideals, had new users play it, collected more usability feedback, and repeated the process until we had a refined and much improved version of the initial prototype. At this point, with the help of the tutorial, almost all users were able to pick up and play it.

A refined version of the original prototype, still featuring the move and rhythm bars. Later these were merged in to one.

This success, in retrospect, also indicates a larger failure; over the course of these design refinements, we had partially achieved the ideal of usability through minor adjustments at the expense of some of our other ideals. The screen had become cluttered as new feedback elements crept in, confusing the eyes of the user. Rather than making the game more accessible, we had in fact made it more complex.

We took the game around to publishers and others who we wanted to partner with us to assist with marketing and licensing and found that in less controlled conditions that the game was, rather embarrassingly, not at all accessible; we had created an esoteric system which could only be understood through a lengthy tutorial.

After this realization, we called a meeting to discuss the future of the project and within an hour we had identified the root cause of the problem and produced a solution. We had been incorrectly interpreting the feedback from our tests and addressing the symptoms of a problem rather than the cause. What the users were asking for (the minor changes) and what they really needed (a more prescriptive core mechanic) were very different things.

The solution was irritatingly simple: to rebuild the game as the alternative button-based prototype, and disregard our self-imposed design restrictions -- i.e. the design ideals.

The button system dictates the required actions to the player through the established iconography of the button -- something to press or to touch. Meanwhile, the closing circle suggests timing. These elements were the key to producing the desired interactions between the video game and the user.

Now, the user was not required to learn each move they were expected to use; instead the core mechanics allowed the user to simply follow along. This, in turn, slightly reduced the theatricality of the experience, but greatly increased the accessibility of the product and the enjoyment users experienced.

We started the development of the new prototype from the ground up in a new engine, and took on board our previous mistakes. We now did not impose our ideals on the product, but instead built, tested, interpreted, proposed solutions, rebuilt and retested, with both the prescriptive and implied feedback of the user always leading the design.

After identifying an issue through test interoperation, a solution was proposed and recorded using a issue tracking software. This was then integrated in to the next build, and again the new build was tested.

The final revision of the B-Boy Brawl button-orientated design. Features a score, a multiplier bar and flashy particle effects.

This process evolved and became more refined over the course of the prototype development and was later utilized to shape and improve content, leading to a product which is enjoyable and intuitive.

The understanding of these processes has led me to consider our actions, break them down and formalize a design methodology to allow others to translate good ideas in to great experiences within limited budgets and timeframes.

This methodology is offered as a framework for a more complete, refined and inclusive process and is created using the collective experience and work ideologies of the members of Mobile Pie, as well as generalizations of Agile methodologies. It is not to be considered as a definitive approach to video game design.

This design approach is driven very much by the product itself, as opposed to a strict envisioning of the product; therefore the role of the designer becomes quite concrete. This unique fact makes it perfect for small teams of multidiscipline staff, such as boutique independent studios or student teams, working without external pressure, in short timeframes, to realize products.

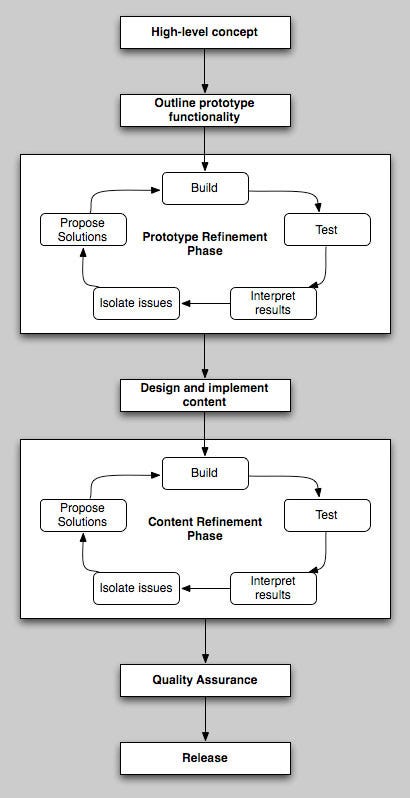

The below diagram shows the phases of Iterative Design Development.

The various phases of Iterative Design Development.

The process begins with a unique high-level concept which is then discussed between the team members with the intention of outlining the functionality of a prototype. The team then works in close proximity to realize the initial prototype, ideally on the target platform with the target technology.

It is recommended that documentation is kept to a minimum and instead the prototype is built very rapidly by verbal communication between the team, with an even split of creative and technical skill sets having input. Of course, this relies on the team members being committed, reliable and democratic.

Once the initial prototype is created, then the iterative design process may begin with the Prototype Refinement Phase; each cycle of this process can be considered in a similar manner as a SCRUM Sprint, where the Product Backlog taken in to a Sprint is, in this instance, a list of Proposed Solutions i.e. alternatives to elements perverting the experience which have been isolated via the interpretation of a test.

The test process and the extraction of feedback from it is very key to producing a meaningful interaction. You may choose to focus group test the product or to pass it around between peers or others you know casually.

It is important not to have strongly defined metrics heading in, but instead to observe the user and their actions, as well as what they say. This is because metrics suggest a predetermined idea of issues within the functionality of system, but, from my experience, you are, as the builder of the system, unable to predict what elements within it which may hinder the desired interaction.

The interpretation of feedback from play testing is a skill which could be covered as an article in itself; however, the ability to listen, common sense, and an understanding of the functionality of video games are all invaluable skills.

Once the team has agreed that the prototype functions as it should with placeholder content, or delivered a vertical slice (a complete playable section of game indicative of final quality), the team must move on to the design and implementation of additional content. The length and complexity of this phase is dependent on the type of project.

Once the content has been designed and implemented then begins the Content Refinement Phase. Dependent on the project this may take more or less time than the Prototype Refinement Phase, but uses the same principals focused purely on how the content functions within the parameters of the core mechanics, as defined during the Prototype Refinement Phase. Large changes to the gameplay should not be made unless absolutely necessary.

After this phase the product is in a strong Beta state and should enter QA with a focus on bug fixing only, after which it is suitable for release.

This methodology focuses on producing a product of high quality, however due to its particular efficiencies it can, when correctly project managed, do so within a controlled time and cost.

The main risk when attempting to scope a project using the proposed methodology is that the time each refinement phase will take is an unknown. In an unrestricted implementation each cycle within a refinement phase is of an indeterminate length and there are an unknown number of iterations.

However, to stop both the time and financial costs of production from spiraling out of control it is suggested that the number and length of cycles with a refinement phase are agreed and fixed prior to the start. Therefore, it is important that before a new build in a refinement cycle is started that all Proposed Solutions are prioritized and then completed in that order so as the most important functional changes are fulfilled first.

However, all other phases, such as content development, can be managed using a traditional waterfall model. By defining strict time frames for each refinement phase (as described above) the project manager is able to give a very defined timeframe and cost for the project.

Although this methodology is proposed for small teams developing unique video game experiences, it has the flexibility to improve the quality of the experience of much larger, more mainstream video games too. In a larger project, the emphasis would be change -- perhaps more toward the Content than the Prototype Refinement Phase.

However, this methodology could suitably be applied to the creation of a proof of concept demo by a small team as a precursor to a larger project, with the feedback from testing placeholder content in the Content Refinement Phase, informing the design of future content.

Its implementation is something that is able to improve the quality of a product in a number of scenarios, however it must be done with thought and concern for the type of team and desired outcome.

Iterative Design Development focuses small, talented teams on finding the correct design to realize a unique and innovative product by building fast and failing fast.

It offers a relatively large freedom and flexibility early on in a production cycle, allowing for a quick and reactive approach to design. It also encourages the collaboration of all disciplines from the start, meaning that teams can start producing straight away, as opposed to one being dependent on the other to finish a task.

It is offered as an evolution of processes refined by Mobile Pie following the construction of numerous products and is informed by our successes and failures, before and after the formation of the company, as well as academic design theory and Agile project management methodology.

I hope that this framework is of use to others in our position and that they may refine and discuss its merits and implementation, further evolving and tuning it for more efficient design development.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like