Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

An article on how game duration is an intrinsic part of the aesthetic qualities of video games that produce meaning and can impact the player.

Preamble : duration as form.

The length of a video game and how it relates to its intrinsic value is a contentious topic, to say the least. I use the term value, not only for its monetary connotation, but to how it can impact and involve the player. A lengthy video game is sometimes synonymous with an effort to deliver an immersive experience, with an ambitious story and tons of content for the player to discover. On the other side of the spectrum, we can think of arcade-type games, pick-up-and play mobile games and such, which are more often than not aimed at short burst of action packed fun.

The assumptions I just made are quite obviously general and most likely erroneous, as video games nowadays are as rich as any other art form, and the plurality of game types makes this kind of shallow classification a pointless task. However, painting a very general image of what duration can say about a video game is made in an effort to try to turn this “parameter” into one that we can analyse as a formal quality that can in itself produce meaning. In other words : the duration of a video game, just like graphics, gameplay and story is a formal aspect that can be considered when we try to do game analysis.

The Witcher 3, Pong and Vesper 5.

A lengthy game like The Witcher 3, for instance, doesn’t occupy the same ‘life space’ as Pong would. One could argue that a player could invest a lifetime into playing Pong, but let me make an important distinction. The Witcher 3 proposes an ongoing story that will only be fully unfolded if the appropriate amount of time is played. The experience of Pong is essentially short and can be repeated as nauseam, with slight variations in play, with the core of the proposed experience remaining intact on each playthrough.

Another example which I would propose works very deeply on game length and ‘life space’ is Michael Brough’s Vesper 5. A beautiful and meditative game in which the player can only make a step every day for 100 days, until he reaches the objective. I have not personally finished this game yet, but this game has taken a place in my life for the past couple of months, and while a play session is very short, the length of each of them becomes longer, as the game displays all previous steps the player has taken in his journey. The depth to which this game works on duration and time itself in videogames shows how we can work with game duration as an aesthetic and formal quality that can produce meaning and impact the player.

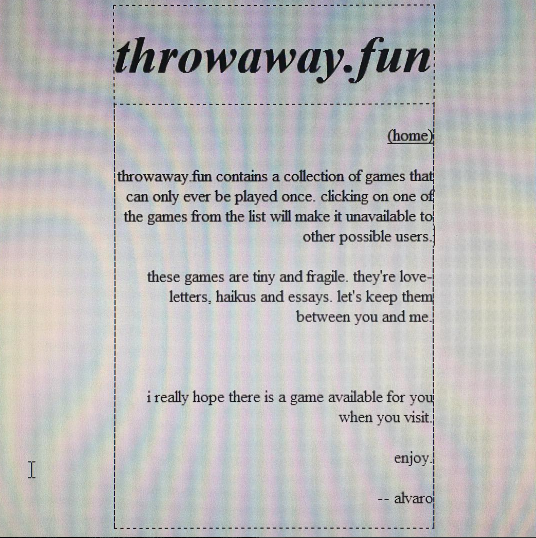

I clarify these thoughts about duration, not to overstate the obvious, but to introduce the reader to the realm of ideas that have been obsessing me and that brought me to make throwaway.fun, a video game portal in which I publish games that can only ever be played once.

This game portal is a humble proposal, an exploration on an alternative way of conceiving games. Instead of aiming for games that either last a very long time, or offer infinite replayability, I aim to make games that only impact one individual. A private conversation between the creator and the spectator.

The initial idea seduced me and motivated me as a game developer. In a short burst of inspiration, I made about 8 games. The reaction to them were varied ; some players refused to play the games, as playing them would mean they wouldn’t exist anymore. Others shared them with their friends, instead of playing them themselves. And the more curious ones, played two or three, bringing most of the website’s content into oblivion.

All that remains is a short and vague description.

Making games for no one.

Making games that can only ever be played once requires a very specific mindset. As a developer, I can only spend so much time on an idea, and as much as possible, they must be simple to make and interesting enough to warrant making them. Conciliating these two requirements is not as easy as it might sound, as everything is more complicated than it initially seems in game development.

I tend to think of these games as short poems that depict a single idea. Tutorial, for example, is an exercise in subtraction. The only objective in the game is to close it. If the player wants to keep playing it, he has to reopen it, which scores him one point. The final objective is to reach 1 million points. Quite obviously, this game presents the player with an absurd objective and it’s very unlikely that any fun will come out of pursuing this repetitive task. As a design exercise however, this game aims to be the simplest video game tutorial possible, where the act of opening and closing the game is the game itself.

Most of the work I try to present in throwaway.fun deals in some form or another with what video games can be. These games require a short development time and play, but they allow me to exercise aspects of game design which I can’t in other forms of video games. This sort of work proves to be very valuable for myself and to players who are willing to accept that games can take many forms.

Closing thoughts.

The idea of making games that can only be played once is not completely new. I remember an apocalyptic game on Newgrounds, a few years back in which the end of the world meant the end of the game. However, this could easily be cheated, as the browser cookies would allow the player to experience the game again. Throwaway.fun circumvents this by plugging all the games to a database, which holds a boolean value into memory that changes as soon as the games are played. None of these approaches is more “legitimate” than the other, but they do indeed change the meaning — and possibly impact — of the work.

On a side-note, a fellow game developer, Simon-Albert Boudreault pointed out that an alternative name for throwaway.fun could have been “One player games”, which I think is much more apt name than the one I came up with. Hopefully I made up for my mistake by using his idea as the title for this article.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like