Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Pentiment game director Josh Sawyer breaks down the design logic behind the games' brain-teasing murder mysteries.

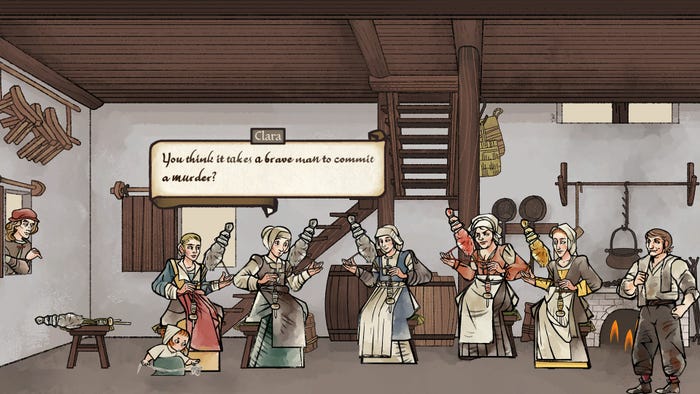

Obsidian Entertainment's Pentiment was one of our team's favorite games of 2022, and for good reason. It's a genuine leap forward for video game storytelling that makes the most of art direction that mimics the aesthetic of medieval illuminated manuscripts—and tells a tale that humanizes an era calcified in the minds of modern audiences by Hollywood epics.

While there's plenty of heady, intellectual fodder at the heart of Pentiment, it hangs its hat (and storytelling structure) on the format of the murder mystery. Players take on the role of Andreas, a skilled painter apprenticing at Kiersau Abbey in the fictional Germanic town of Tassing.

The team at Obsidian shared an interesting fact in advance of the game's release: most of the crimes Andreas solves in the course of Pentiment do not have a definitive "canon" perpetrator. Players chasing different investigative threads will have plenty of reason to think they've correctly fingered the guilty party, but the open-ended story serves a larger (and more interesting) purpose.

So if there's no definitive murderer, why make a murder mystery game at all? We pinged game director Josh Sawyer last month to ask about the interactive murder mystery format—and why Obsidian stuck with it even when there was no intent to give players the satisfying answers they might crave.

Heads up: from hereon out, there will be light spoilers for Pentiment.

In 1980, Italian author Umberto Eco released the book The Name of the Rose: a medieval murder mystery that would become one of the best-selling books ever published (and fun fact, its influence on video games goes back further than Pentiment. An adaptation of the book into video game form called "La Abadía del Crimen" was released in 1987, and a level inspired by the book appeared in the expansion for Thief: The Dark Project).

Sawyer explained to Game Developer that The Name of the Rose was a strong inspiration for Pentiment—so strong that it's cited in the credits as a "source" for the game. "I just thought the idea of a central mystery would be a compelling one within this context," Sawyer explained.

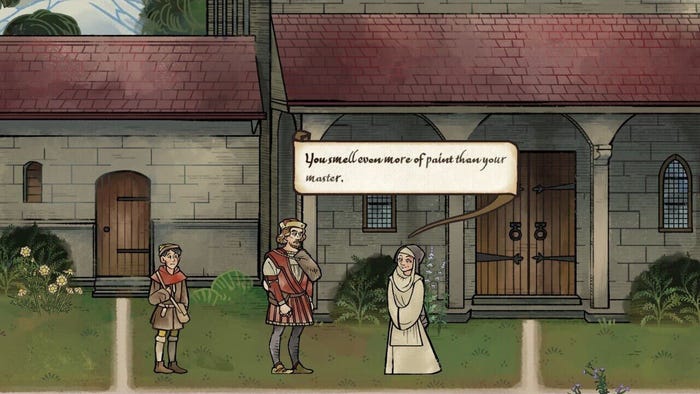

To set up the mystery, Sawyer and his colleagues referenced the works of Agatha Christie and their many adaptations. Though Pentiment doesn't play out like a Christie mystery, it certainly opens like one. Sawyer cited the prolific author's practice of introducing the murder victim to the audience in key early scenes—along with all the people who don't like them, and would have something to gain from their death.

"That was the foundational layer in establishing those relationships in the game," Sawyer said. Andreas and the player get to witness the various parties who react to the arrival of Baron Lorenz of Rothvogel. One townsperson argues with him. A widow emerges from her home to curse his name, and the abbey's Mother Cecilia recoils at his arrival.

In this dialogue-driven, choice-heavy game, players now have a foundational set of choices they can make decisions on after The Baron's body is found under the giant mural of the Danse Macabre. Now they can begin the hunt for whoever had the means, motive, and opportunity to do the killing.

But players hoping to Benoit Blanc their way through Tassing found themselves without one conventional crime solving tool: the alibi. Sawyer explained that in designing the various murders, the team at Obsidian originally considered an option to determine alibis—if any of the suspects could securely identify that they were somewhere else at the time of the murder.

The "alibis" feature even made it into the first prototype of Pentiment, but not the final game. "We got rid of it," he explained. "All it does is exclude [suspects], and we're not trying to find a singular suspect, we're trying to rule people in, not rule them out."

He went on to say that the point of the investigative process in Pentiment is to have players hone in on the motive. Determining the "means" is relevant to The Baron's murder, but not to the second or third investigations in the game's following acts.

Putting the motive at the center of the player's investigation goals also helped Obsidian create a clear test for the player's efforts and a rudimentary pass/fail system. After gathering evidence for a few days, players are thrust in front of the Archdeacon—an official investigator sent in by the State. He's here to throw a monk accused of the murder through a Kangaroo court, but players are given a chance to convince him that a different, better suspect exists by laying out what they know about the motive.

Interestingly, Sawyer explained that the Archdeacon is "biased." The if-->then logic of the Archdeacon is not evenly balanced—it's weighted to favor convicting the widow who cursed the Baron, and against a monk the Baron might have been blackmailing.

Therefore getting Prior Ferec convicted of the murder is a more "difficult" task. (Does it say something that both me and my fiancé managed to convince him in our playthroughs of the game?)

As mentioned earlier, none of the listed suspects are canonized as the definitive murderer—and Pentiment is deliberately designed to incentivize uncertainty. Players might find some suspects highly credible, but be reluctant to convict them. "It's meant to make the player not look at it from the perspective of 'I definitely think this person did it,' because it's difficult to have that level of confidence."

"It's more to [ask] 'who do I value? What do I think is important in this set of bad circumstances, which is the least bad from my perspective?'"

Sawyer called the choice to leave the exact killer's identity uncertain "foundational" in our chat. "I honestly find logic-based 'one true solution' murder mystery games not very satisfying personally," he said in reflection. He also observed that in a historical context, justice "doesn't work the way you think it does," especially in an era predating forensic science.

The goal of solving a murder like the ones in Pentiment is to seek some kind of justice—to right a wrong inflicted by a death. Sawyer observed that justice often can feel "hollow" in how it's practiced, especially when there isn't clear certainty in who did the crime. If you have any sense of doubt in a case—you're left wondering if the killer got away, and if you might have punished an innocent person.

He argued that a story where the killer is definitively identified, and they confess to the crime or are karmically punished by some kind of petard-hoisting death is "nice," but not fulfilling in this setting. Tacking away from that certainty gave players more responsibility over the dramatic events that follow the murder, and gives them a chance to better roleplay in this setting and reflect on their own values.

Maybe this dog killed The Baron.

If Pentiment did identify exactly who killed the Baron (which to be clear for those who've finished the game, is far different from who orchestrated his death), Sawyer argued that it would remove that sense of responsibility, and the punishment for the crime would just be "the mechanism of the state in action."

Obsidian's design goals here are an interesting contrast to ZA/UM's 2019 game Disco Elysium, where players drunkenly race to solve a murder with a definitive killer. Only in that game, the killer and victim are not introduced in the early hours, and the question of state mechanisms is very closely examined in its final hours.

There's value in both design styles, of course. It's then worth asking—when you're crafting such a mystery experience, how do you know you're making a case worth solving?

If you're thinking of making your own interactive murder mystery, you might benefit from the process Sawyer and his colleagues used to playtest Pentiment.

The first step in playtesting the game actually began with the thirty-minute vertical slice the team first created. About seven to eight friends of the development team were enlisted as playtesters, and they were able to give concise feedback on the game's base mechanics.

The next group of playtesters came from the "friends and family" group. They were tasked with testing the Alpha version of Pentiment. Sawyer said this group was able to give useful feedback on the game's third act, when plot points from acts one and two come to a head.

"There were certain like plot threads that just were not coming through, and people were like 'I didn't pick up on this thing at all,' or 'this didn't feel foreshadowed in any way' or 'this character's death felt extremely unsatisfying and left a bad taste in my mouth.'"

Feedback like that for act three helped the team improve plot points from acts one and two. A common problem was that a character would speak to the player in act one, not appear meaningfully in act two, then have a key moment in act three. "The team never sees that stuff because we all know everything," he noted. "So we're looking at it from like a quality and functionality sort of perspective."

Sawyer said that in this stage, feedback from players also helped flag that one investigative minigame in act two wasn't very fun.

It's a bottle-shaking game where players are helping a blind nun identify what bottles a possible suspect in another murder knocked over.

The blind nun in question.

Sawyer said that this feature in the shipped game is "completely different" based on what came before, and that players initially found it confusing and not fun. In a "mechanics-light" game like Pentiment, Sawyer said the minigames weren't meant to be hard, but immersive.

Chatting with Sawyer meant we mostly dived into the nuances of storytelling decisions and design choices—but Sawyer was eager to spotlight his colleagues outside the narrative or design departments who sold the impact of Pentiment's murder mystery too. He credited Cathy Nichols' animation direction and Hannah Kennedy and Soojin Paek's visual design for both bringing this abstract illuminated manuscript art style into something you could tell a murder mystery in.

Sawyer noted that Nichols had to animate between 150 to 200 unique characters, and that she went the extra mile creating unique death animations for each suspect killed in response to the Baron's murder. It's a key moment for Pentiment, since each of those deaths puts a punctuation mark on the player's decision to name the suspect of their choice.

Watching Ferenc run away from the executioner and beg for mercy before suffering a botched and bloody beheading wiped away much of the anger and suspicion I personally felt for him—and it was chilling to learn that how each other suspect dies can be equally macabre.

Kennedy was behind Andreas' finished masterpiece that's unveiled at the end of act one, and Park created the Dance Macabre mural that hangs over the Baron's corpse in Kirseau Abbey's dining hall. If you think about the great tradition of murder mysteries, it's striking visuals like these that help sell the heightened stakes of an individual death.

In a story that hangs on the work of medieval artists—filling this game with art that could strike the soul was no easy task.

There's more to a murder than just finding the killer—that's true in real life, and equally true in spinning an entertaining story out of such a horrific act.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like