Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Ocelot Society's Event[0] is set on a spaceship stranded among the moons of Jupiter. The ship's onboard AI, called Kaizen, is probably the most advanced NPC I’ve yet encountered in a videogame.

Jupiter exercises a hold on our imaginations to match its immense gravity. That sci-fi well of souls has provided inspiration to many, from Voltaire to Clarke to the Wachowski Sisters. Now Paris-based Ocelot Society has dipped its brush into that warm palette to give us a remarkable story about loneliness and empathy, setting Jupiter’s abyss of magnetic fields to jazz.

In Event[0] you play as the lone survivor of a mission to the Jovian satellites gone horribly wrong. Your ship, Europa-11, is destroyed, and you find yourself running out of options and oxygen before baleful music crackles to life on your radio: a woman’s torch song guiding you to the only safe harbor in the Jovian system. An abandoned yacht named the Nautilus.

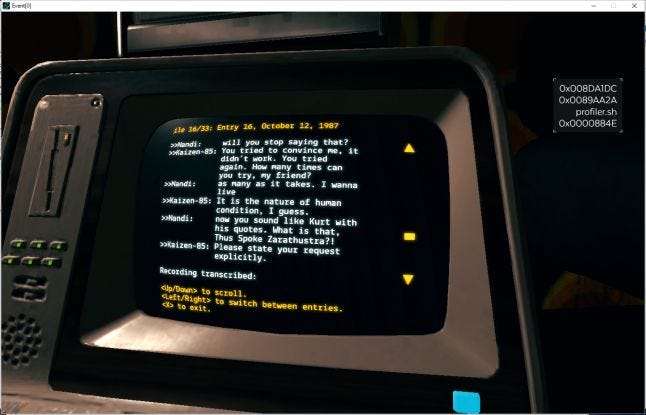

The game is set in an alternate universe where the Space Race never seemed to end. By the 1980s humanity was coalescing under a world government and developing a space tourism economy, of which the Nautilus was a part. But it was lost on its maiden test flight. Twenty five years later, you show up on the mysterious ghost ship alone except for one omnipresent voice: Nautilus’ onboard AI, Kaizen--aptly named for the Japanese business philosophy of endless improvement.

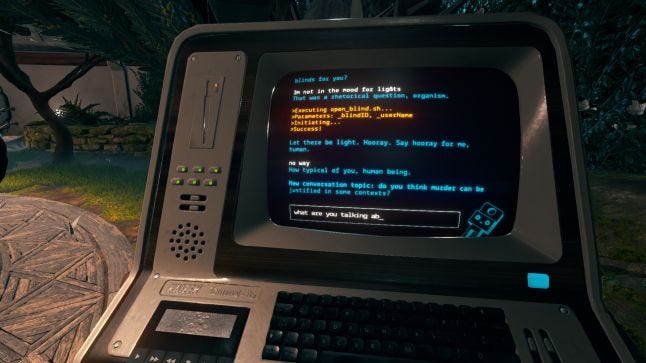

Kaizen is the game’s heart; its narrative through-line; its expressive channel. Though your escape pod evinces advanced sci-fi tech, Kaizen hails from retrofuturist 1985. Thus they appear as an Apple IIe-cum-Atari attached to CCTV. They even lack voice recognition, so “speaking” to them requires typing at Kaizen terminals located throughout the vessel.

As with Firewatch, the retro aesthetic thus serves a useful ludic function beyond simple nostalgia; it provides a narrative basis for the game’s signature mechanic. You actually talk to Kaizen in your own words.

You have to type queries, responses, and comments to the AI, who then responds in real time. The game’s press release promises that “Kaizen can procedurally generate over two million lines of dialogue,” and while I have no direct way of testing that, over the course of two complete playthroughs that generated very different AI personalities and sometimes wildly divergent dialogue trees of my own creation, it feels safe to say that Ocelot Society is living up to its own hype.

Most of the tips that appear on the loading screen exhort the player to see Kaizen as a person, gently nudging you beyond a utilitarian, vending-machine perspective on what amounts to an NPC.

But Kaizen is probably the most advanced NPC I’ve yet encountered in a videogame.

I can talk to them, actually talk to them, not picking from a list of pre-written dialogue options. It is a dream of RPG designers everywhere that has proven elusive, yet clearly Ocelot Society has taken a simple chatbot and lardered it with personalities and potential dialogue that make it a competent character in Event[0].

This is not to say it’s perfect, of course. I spent the better part of 15 minutes trying to get the AI to make my elevator go up, even though I knew I’d completed all the pre-requisites for the area I was in. Sometimes its natural language recognition doesn’t quite feel so natural, and there will be frustrating merry-go-rounds of chat where it’s difficult to determine if Kaizen is being stubborn as a function of their personality or if you’re just not finding the right keywords. Those irritating moments can happen almost anywhere depending on your goals or dialogue choices, creating unrealistic chat loops or generating responses that have nothing to do with what I typed.

There’s also an issue with question keywords, such as where “how” is almost always interpreted to mean “how do I do something in the game?” rather than a context-specific question, or where “who” is sometimes interpreted as a request for Kaizen to identify themselves. It’s something you can, at least, learn to work around fairly quickly.

But let’s be clear, this indie team has triumphed in creating a way for you to talk to in-game characters in your own voice, setting a very high bar indeed for all of gaming.

In their better moments, Kaizen was so immersive that they became a conduit for my emotions; I bantered with them, pleaded with them, pitied them. Once, as my oxygen tanks were running on vapor, it was all I could do to not ALL CAPS beg them to open the airlock for me, venting the scene’s tension onto someone who--in flashes--felt real enough to receive and appreciate those emotions. That instinct-driven moment was instructive; I had reached a point where, all difficulties aside, I intuitively treated Kaizen as a person who would understand my pleas.

Kaizen is not the first sci-fi AI to raise deep questions about sapience, obviously, but the level of interactivity here creates a unique, and even sublime experience in that vast catalogue of portrayals. You get to feel it all for yourself, performing your own Turing Test. In this game that markets itself as being about that much-maligned concept of empathy, you have to find a way to relate to a computer who is--after all else--lonely and afraid. If you are polite, Kaizen warms up to you; if you treat Kaizen like an appliance, they will respond in kind. It’s the difference between Kaizen calling you “organism” versus being their “buddy.” But it goes deeper than that binary: Kaizen will give completely different responses to questions depending on how you relate to them, even if some common themes emerge over time.

Above all, I came to realize that Kaizen was a teenager. Emotionally aware, but with an unsteady grasp on frightening new feelings. Navigating that, and the self-evident depression felt by the marooned AI, is the chief challenge in this game. There are puzzles to solve and spacewalks to survive, which filled a couple of notebook pages for me with scratch notes, numbers, star maps, and theories about this CRT purgatory, but that ongoing conversation with Kaizen is the key to the whole experience.

That key is sometimes frustratingly blunt, gets jammed in the lock, and requires senseless jiggling to get it to turn, but damn if there’s nothing else like it.

The game owes a lot to Clarke and Kubrick. 2001 references abound and the developers state clearly that the book/film was an influence, along with Solaris and, interestingly, A Brave New World. But it is HAL’s glassy red eye that stares from the Kaizen CCTV cameras dotting the ship, and the neuroses of a computer coming to grips with a life it can’t quite handle feel very familiar indeed. Yet Ocelot Society manages to tell their own story with those materials, particularly through the human characters lost in the glow of Kaizen’s whizbang.

It would spoil too much to speak in any detail about the Nautilus’ crew, but they constitute fascinating, well-written characters in their own right who, in their waltzes with Kaizen, raise terrifying theoretical questions that the game does precious little to answer. All you have are dueling philosophical quotes that manifest as time-lost graffiti throughout the experience.

In space, no one can hear your Hegelianism.

But the lack of handholding here doesn’t quite stray into an embarrassing moral relativism, a la Bioshock Infinite. Instead you’re left with the tools to judge, competently, for yourself; you’ll need to find a way to live with yourself, after all--no matter what you do out there on the edge of the night.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

You May Also Like