Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How do systems and story interact? This article examines how Night in the Woods puts the mechanics in support of the story - not the other way around.

Every video game has three essential components: mechanic, aesthetic, and story. Designers can use any one of them as a foundation for the others, but the most common approach has always been to focus on the mechanics. This means that every other aspect of the game is designed in support of its systems. Things like the story beats are given a backseat to economy, combat, or skill progression. The mechanical approach to game design is perfectly valid, but it’s not always the best creative option. Sometimes it’s the story that really matters — not the systems. (Aesthetics are almost never the seed from which a game grows).

Crosstown traffic

Games like Civilization lean so heavily on their mechanics that narratives are mostly emergent, but other titles have the opposite inclination. Infinite Fall’s Night in the Woods is clearly of the latter variety. The gameplay is really just there to support the story.

Spoiler alert: the following article contains minor mid-game spoilers.

Meet Mae

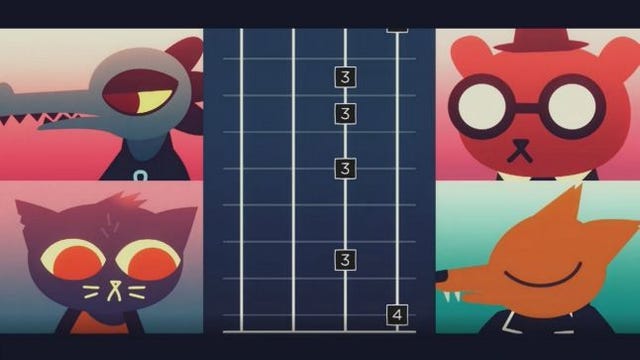

Night in the Woods takes place in the dying town of Possum Springs. The main protagonist is Mae: a recent college dropout suffering from long-term issues related to her mental health. (She’s noticeably depressed throughout the game, but also describes the symptoms of a condition resembling Dissociative Disorder). She happens to be a cat. Reconnecting with her friends and family, Mae tries to pick things up where she left them a few years earlier, but soon realizes that she’s no longer the same kitten. The game follows Mae as she struggles to communicate with her mom and dad, spins the yarn with neighbors, and hangs out with her best buddies: Bea, Gregg, and Angus. (They’re animals, too). Supporting their friend in her darkest hour, these three prove to be the most important figures in Mae’s life. Everything else is up for interpretation. (You really shouldn’t be taking Night in the Woods at face value).

Meet Mae's friends

You spend the game chatting with various people around Possum Springs. The dialogue is really what matters most, but all of this meowing around town still gets broken up with a series of gameplay vignettes. Deeply embedded into the narrative, the mechanics of these minigames were clearly adapted to the story — not the other way around.

Encounters with the fine people of Possum Springs aren't always pleasant

The only thing which Mae seems to like more than pouncing around town is sleeping. (She apparently spends ten hours a day in the sack). There’s a pretty good reason for this: she has a very active subconscious. Most of her dreams are actually minigames consisting of jumping puzzles that require players to find each member of a musical ensemble. Perched atop hidden parapets and towers, they’ll only start playing when you get in close enough. These minigames communicate Mae’s mental state by focusing on her inability to achieve peace of mind. The harmony which you create for Mae is only transitory: the discord of her anxiety and depression turns the music into noise shortly after you complete the ensemble. This is Mae’s conscious mind reasserting control as she wakes up. Her comfort disappears with consciousness.

Time for a catnap

Mae's dreams are about the search for inner peace

The search for harmony reappears in yet another series of minigames: band practice.

Mae gave up on making music in college, but she used to play bass. Gregg somehow talks Mae into rejoining his band, so you end up struggling through a button-mashing minigame similar to Guitar Hero. Failure is thankfully an acceptable outcome because you’ll definitely hit a few wrong notes. The game seems to want this to happen: perfection comes with a surprisingly steep learning curve. Night in the Woods even punishes you with an ear-piercing BONG! every time you miss a beat. Bea, Gregg, and Angus won’t hold back about your poor performance, either. Stumbling through band practice is part of the point, though: you’re meant to feel Mae’s awkwardness at coming home after so long an absence. Things have changed. Mae’s now an outsider. She’s made a few steps in the right direction, but getting back into sync with Possum Springs will take a lot more time and effort.

Band practice is a reminder that Mae has become an outsider

The story is really about Mae, but most of the other minigames focus on telling us a thing or two about her friends.

Gregg is a pretty outgoing character on the whole. (He can frequently be found shouting and flapping his arms wildly). Bea claims that Gregg is bipolar, but the game never actually shows him experiencing any mood swings. He comes off as pretty cheerful and optimistic. With his black jacket and Pickelhaube, he’s also kind of a punk. These aspects of Gregg’s character are reflected in one of his minigames: smashing light bulbs with a baseball bat. (Sometimes he’ll pitch you a beer bottle, too). This may not sound like a very sensible way to spend an afternoon, but who’s going to argue with a fox? Since the idea behind this minigame is to make you feel every bit as rowdy, impulsive, and passionate as Gregg, you just have to climb onto that dumpster and whack away at whatever comes your way for a while. You’ll understand later. (Maybe).

Foxy lady

You’re given a choice to hang out with Bea over at the Fort Lucenne Mall around halfway through the game. Mae’s definitely broke, so don’t imagine that you’ll be doing any shopping. You’ll actually be doing some shop-lifting. This requires you to guide Mae’s trembling hand into a display case at URevolution and snatch a belt buckle without the clerk noticing. (You can also make a distraction while Bea does the dirty work). Stealing is wrong, but don’t feel too guilty: this minigame is an exploration of Bea’s character. Motivated by a strong sense of responsibility, some harmless mischief is the perfect way to poke at her personality. (She gives back any stolen merchandise). Bea feels crushed by the weight of her social obligations, so shoplifting with Mae is a kind of catharsis. Players in other words get to be complicit in her much needed letting loose.

You can distract the clerk for Bea if your stealing skills aren't up to par

Angus doesn’t appear much in the story, so it seems oddly appropriate that his minigame never actually involves spending time with him. Lending a helping hand whenever there’s a problem, he’s known for being exceptionally warm and nurturing. Angus even bakes up some brownies for you late in the game. (His response to being underfed as a cub is to cook for others). Gregg decides to finally repay some of these good deeds by salvaging a robot for him that used to be in the Food Donkey, so you get tasked with figuring out which parts go where. (You can drag and drop them into almost any position). Night in the Woods hardly ever puts Mae and Angus in the same room, but still communicates quite a lot about his personality. Learning about him through other characters like Bea and Gregg, you find out that he’s a bit more technical than your average bear. Angus for example is known for his computer hacking. He tends to be rational and scientific, so what better way could there be to explore his character than some engineering?

The Food Donkey must have been a pretty creepy place

Game designers tend to focus on systems, but story is also a perfectly valid component to privilege. Night in the Woods does so with gusto. Infinite Fall wrapped the game’s mechanics around a story about Mae’s daily struggle to keep on keeping on. This approach can be seen in the minigames. Deeply embedded into its narrative, these are part of Night in the Woods for a specific reason: character building. Each one communicates a thing or two about the lives of Mae, Gregg, Bea, and Angus. Proving that mechanics don’t always drive the experience, these are mostly in the game to provide support for the narrative. The result is an artwork that knows where its greatest strengths and weaknesses are — and its heart.

This article was reproduced from "Narrativizing Night in the Woods," posted to SlowRun on March 10, 2018.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like