Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Part Two. These are my memories... Growing up in a world with 3 TV channels and paper mail... My years writing some of the earliest 8-bit games (CRISIS MOUNTAIN, DINO EGGS, SHORT CIRCUIT)... And now reviving my best-selling game as DINO EGGS: REBIRTH.

1981. Many computer games were home-grown and distributed on audio cassette tapes stuffed in plastic sandwich bags with sparse photocopied instructions.

I was four years out of college and seeking creative employment. Reading ads for such games in the budding computer hobbyist magazines like Creative Computing, Byte, and Compute!, I wondered if any of these odd new machines could reproduce the thrills I experienced in the arcade corners of the local taverns and 7-11’s (as I talked about in my previous post).

I was four years out of college and seeking creative employment. Reading ads for such games in the budding computer hobbyist magazines like Creative Computing, Byte, and Compute!, I wondered if any of these odd new machines could reproduce the thrills I experienced in the arcade corners of the local taverns and 7-11’s (as I talked about in my previous post).

Could I play Donkey Kong at home? Could I write something like Donkey Kong at home, and get others to play it in their homes?

And, needing a job, I wondered – Is anyone making money doing this?

Which of the machines described so breathlessly in the magazines were going to stick around? The Tandy Radio Shack TRS-80? The Commodore PET? The Texas Instruments TI-99/4a? The Atari 400? The Commodore VIC-20? The Timex Sinclair 1000? Or the Apple II? I couldn’t afford to buy any of them.

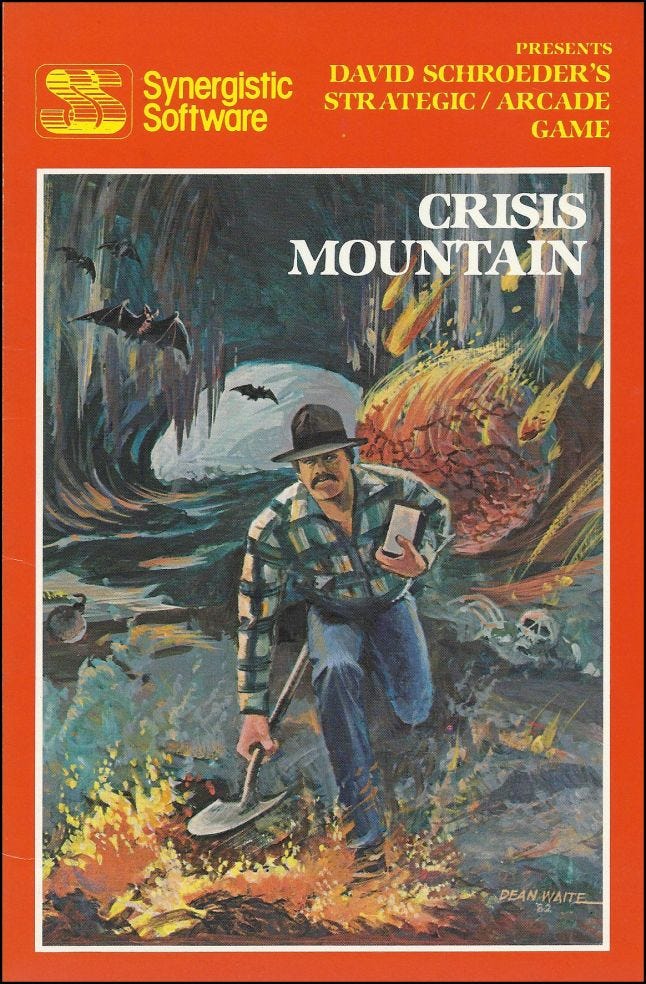

If the nearby Seattle Central Community College had stocked their computer lab with something other than Apple II’s, would I have written my first game Crisis Mountain for that type of computer? Yes, of course, I would have. But that lab had Apple II’s, and so that was the mountain I began to climb.

Signing up for a lab course that granted me access to those Apple II’s, I explored the nooks and crannies of that amazing machine, looking for the canvas on which I could try to re-create Donkey Kong.

Signing up for a lab course that granted me access to those Apple II’s, I explored the nooks and crannies of that amazing machine, looking for the canvas on which I could try to re-create Donkey Kong.

The two text screen pages? No. The two Lo-Res graphics pages? No, too chunky. The two High-Res graphics pages? Ah-Ha! There were the tiniest dots!

I quickly wrote a game loop in AppleBASIC that mimicked the bones of Donkey Kong in High-Res graphics – it was a jerky little line running back and forth among rolling dots. The movement on the screen was clearly not fast enough to recreate the excitement of Donkey Kong. AppleBASIC didn’t go deep enough.

So I soaked up every book I could find in the computer lab and taught myself 6502 machine code. There weren’t many tools to make this process easier, but those that I found were precious. Thank you, Roger Wagner! Thank you, Call A.P.P.L.E! Thank you, Gibson Light Pens!

So I soaked up every book I could find in the computer lab and taught myself 6502 machine code. There weren’t many tools to make this process easier, but those that I found were precious. Thank you, Roger Wagner! Thank you, Call A.P.P.L.E! Thank you, Gibson Light Pens!

Computers are now so deeply woven into our culture, I strain to remember how they astonished me at the time.

But all this was new:

Computer memory is brittle and fleeting. Without power, the work of an hour (or two) simply disappears. Gone! Saving one’s work is not intuitive, and there is no automation or safety net for the process. This is scary new.

When something goes wrong, you re-boot. The previous paradigm for fixing things was to give them a kick, or to pound on them with your fist. That doesn’t work with computers. This is weirdly new.

Of course you break the ‘rules’ and write self-modifying code. You must, in order to fit a decent game into only 48K of memory. Such code is like a road-building machine that reaches ahead of itself to pave the path that it is about to travel. This is crazy new.

There’s no such thing as a random number. There’s such a thing as an effectively unpredictable number, but that’s not the same. This epiphany makes me feel like Dorothy discovering the Wizard of Oz hiding behind the curtain. Yes, I am literally making everything up as I go along, and every layer of it is contrivance and artifice. This is divinely new.

Forgive the cliché – but it was a golden age – my golden age.

And for this creative introvert, it would last only a few years, ending far too quickly.

Because each bit, each byte, each pixel, each click of the speaker, each check of the joystick was mine, and mine alone. To each of these features I had direct and exclusive access at a permanent address. Everything stayed where I put it. To this day, if you play the original Crisis Mountain, every byte in your computer is there in exactly the same place as it was on my computer.

Between me and an audience, this was as close as I would ever get to a Vulcan mind-meld.

How would a running figure on screen “know” where the solid ground was?

How would a rolling boulder “know” where and how it could alter its path?

There were no tools to automate the relationships between screen co-ordinates and the behavior of animated images.

The computer accepted only raw numbers, and every bit of every number was precious, so pencil and paper were essential to figuring all this out.

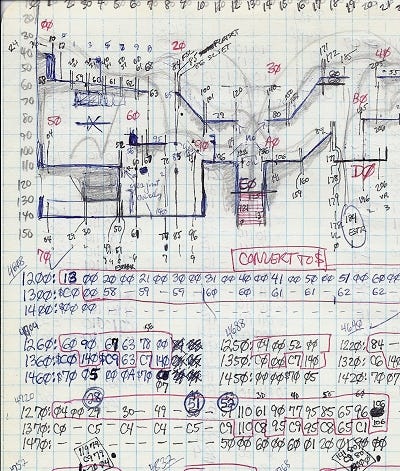

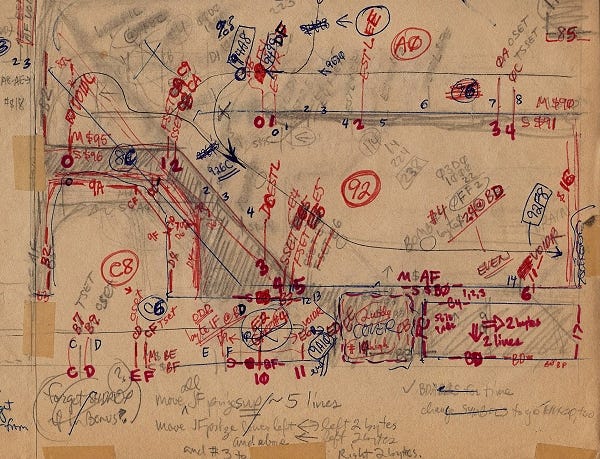

Above and Below: Here I am giving structure to the action on the screen by graphing, calculating and condensing huge lists of numbers on paper. Then I would enter these numbers into the computer one at a time.

I completed Crisis Mountain and got my first advance on royalties from Synergistic Software. It was one of the proudest moments of my life. I bought an Apple II+ for myself and took it home.

Now – how could I make my second game even better? What would I write next?

To be continued...

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

These are my memories... Growing up in a world with three TV channels and paper mail... My years writing some of the earliest 8-bit games (CRISIS MOUNTAIN, DINO EGGS, SHORT CIRCUIT)... And now reviving my best-selling game as DINO EGGS: REBIRTH.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like