Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Why slowness in modern game design is a good thing.

My former professor at George Mason University, the venerable Mark Sample, gave a talk at the University of Kansas yesterday entitled "Playing without Power in Videogames." He focused on the pervasive trope of games as power fantasies, making the player-character more powerful as a game progresses. Professor Sample showcased a few games that reverse this paradigm by stripping power away or least twisting it in some way--JFK: Reloaded, Calabouço Tétrico, and Italian studio Molleindustria's new title, Unmanned.

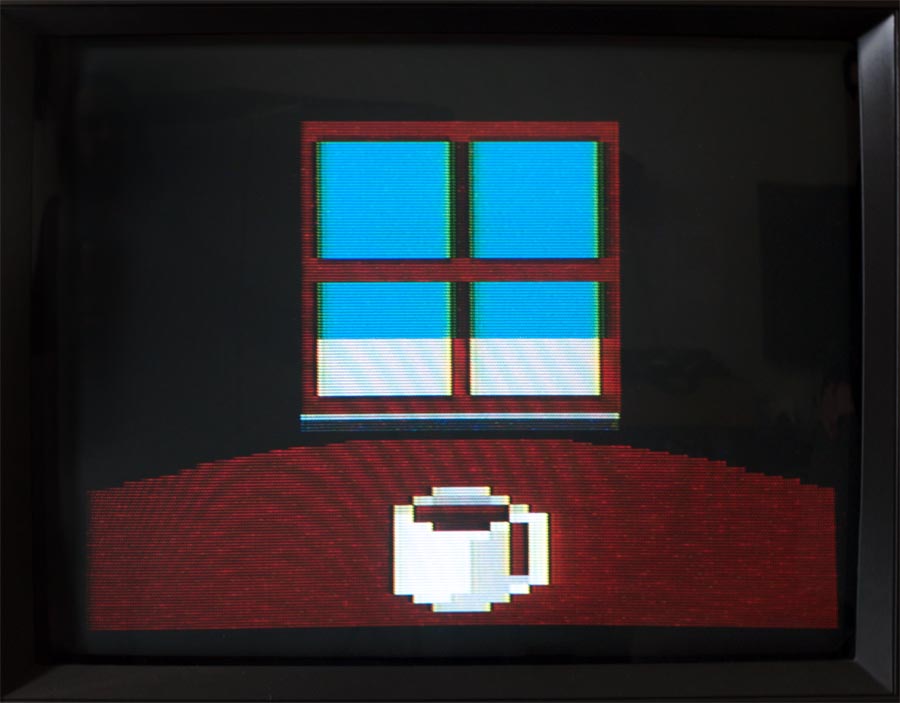

Unmanned |

Unmanned is about a U.S. military drone operator working at a remote base in the (American) desert. Instead of blowing up terrorists, the player spends most of their time controlling the man's daily routine. Waking up, shaving, driving to work, flirting with the coworker, playing videogames with the son at home, trying to fall asleep. It's a commentary on the United States' drone strikes as well as on games as a medium. You can play it here.

It reminded me of another game by Molleindustria I played in Prof. Sample's "Videogames in Critical Contexts" class a few years ago: Every Day the Same Dream. Another quiet, pensive game about playing the routine of a middle-aged man's daily schedule to and from work. You can play it here.

Why this focus on slow-paced routines? Along with the stripping of power comes with the stripping of speed and action. We bemoan today's ADHD game culture; big-budget titles are about quick sensory overloads of gratuitous violence, and successful casual games are about playing in two-minute Angry Birds intervals. But beneath the surface, game design has seen a huge shift in the other direction. Maybe it's a reaction to the chaotic post-9/11 world or simply a product of better technology, but the past few years have been a boon for slow games. There have always been hints of slowness in games, from Cyan's Myst to Nintendo's The Legend of Zelda. But we're starting to see works where the slowness is the entire conceit of the game.

Shenmue |

One of the first prominent examples of slow gaming was Sega's Shenmue, ahead of its time in 1999. Alexander Galloway calls this "pure process" in the first chapter of his book Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture.

"One plays Shenmue by participating in its process. Remove everything and there is still action, a gently stirring rhythm of life. There is a privileging of the quotidian, the simple. As in the films of Yasujiro Ozu, the experience of time is important. There is a repitition of movement and dialogue ('On that day the snow changed to rain,' the characters repeat). One step leads slowly and deliberately to the next. There is a slow, purposeful accumulation of experiences."

The game took an unprecedented $70 million to create, and was a relative commercial flop upon its release--it didn't help that it was on Sega's doomed Dreamcast console. The sequel Shenmue II was released a few years later on the Dreamcast (and strangely, the Microsoft Xbox as well), but it too failed to become a hit. Speculation about a third game in the series has amounted to nothing in the years since.

So are big-budget slow games doomed? Not quite. While fast-paced multiplayer shooters dominate the Western gaming landscape, open-world series like Grand Theft Auto and The Elder Scrolls continue to sell millions. And as Professor Sample pointed out, there are even a few big-budget games like Heavy Rain that share Unmanned's morning-routine gameplay. Then there's Access Games' Deadly Premonition, with zero fast-traveling in its open world and an in-game clock that makes a full day take eight real-world hours. It forces you to focus on the game's slowness, and throughout the game you're told by NPCs to "slow down." While these games still give in to the need for player empowerment and action-packed setpieces, much of the essence of Shenmue's pure process is retained. Players of these AAA titles still relish exploring game worlds and becoming a part of the "slow, purposeful accumulation of experiences."

But it's the increasingly-powerful independent game scene where slow-gaming has begun to thrive in its most distilled form. Molleindustria's games, along with other cult hits like thechineseroom's Dear Esther, Ed Key's Proteus, and anything by Belgian arthouse studio Tale of Tales, strip away any semblance of "fast gaming." Many people question whether these games are "games" at all, since they often feature limited player interaction other than walking around the gameworld pondering its themes.

Ian Bogost's A Slow Year

A Slow Year"For me, the Atari is a slow machine. The rush of setting up scan lines before the electron gun reaches a particular part of the screen, of 'racing the beam' as we call it--that part is fast. But the experience of programming it is slow. Every cycle counts. Nothing is wasted. It's computational Jainism.

Morevover, there's no rush to finish. More than thirty years hence, there will be no more upgrades, no more gimmicks, no more killer apps. For once, it's possible to plumb the depths of a game console without worrying about competition, accessories, upgrades, expectations, shelf space. As I reflected on the concept of A Slow Year, I realized that I wanted to let this slowness become the game. It would be a game about sedate observation, but one that would embrace gameplay more earnestly than did Guru Meditation [one of Bogost's other games]. The slowness would be somehow intrinsic to the goals and action of the game, rather than exerting the force of a pun upon it. And it would become a game whose development time and release date I wouldn't let worry me."

Finally, the games industry has become old enough that we can reflect on our past to meditate on our present. This falls in line with William Shakespeare's sonnets, reflections on a poem structure dating back centuries before his birth, or cinema's recent reflection on silent film in a modern context with Michel Hazanavicius' The Artist. It's no coincidence many of today's other pensive independent games, fromProteus to Terry Cavanagh's Don't Look Back to Jason Rohrer's Passage, borrow art styles and structures from the medium's past.

Clearly these slow games tap into some sort of unfulfilled need for players to become part of Alexander Galloway's "pure process." The industry's roots in arcades have been holding it back--people still think games should be goal-oriented adrenaline-pushers. But the medium and its audience have matured, and digital distribution makes it easier than ever for independent game designers with "slow" ideas to have their voices heard. We've reached the point where slow games are commercially viable. And it's only going to get slower.

[Also posted on my personal blog, A Capital Wasteland]

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like