Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Many video game genres seem to be tied to the long take (shot-in-depth) as their dominant style of visual narration. This raises an important design question: How can we create rhythm and pace under conditions of limited montage options?

In this article I will deal with an important design question: How can we control pace and create rhythm under conditions of limited montage options? In order to find answers to this question, I will first identify a number of motion types and have a look at how video games make use of them in their construction of screen events and their management of players’ experience density. Later on I will have a look at how video games that are built around the long take (shot-in-depth) make use of style elements and punctuation devices to create rhythm and pace, and to delineate scenes and sequences along an uncut visual continuum.

Motion Types in Moving Pictures

The types of motion in moving pictures (including video games!) can be presented under three broad categories: Primary, secondary and tertiary motion.

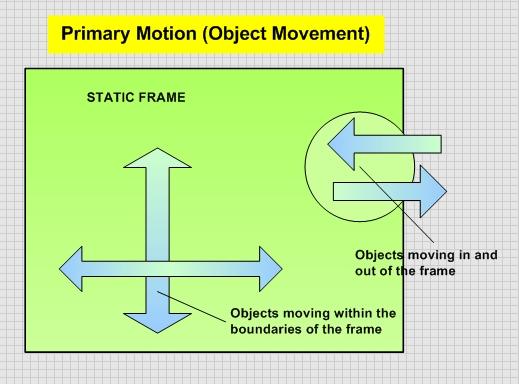

Primary motion refers to object movement. It’s the archetype of motion in moving images. It can be best exemplified by objects or persons moving within, or, in an out of the borders of a static frame. Most often a movie based on primary motion would be criticized as being too “theatrical” since the camera moves rarely, if at all. However, a great number of games are built on primary motion. Examples of such games would be Tetris, Centipede or Space Invaders, all of them being games that feature a static frame with objects and characters moving within, or in and out of it.

Primary Motion (Object Movement)

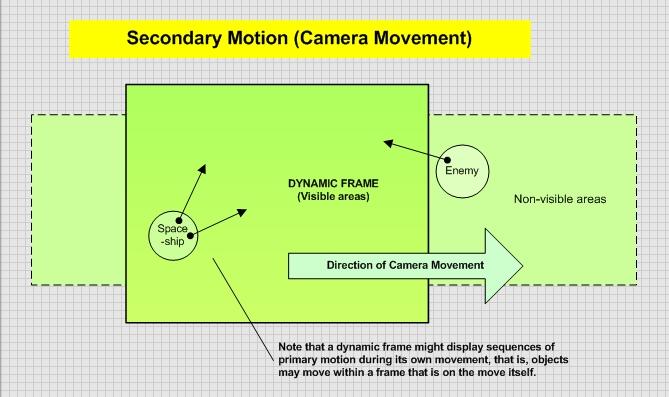

Secondary motion denotes camera movement. The frame is now dynamic and the camera performs a variety of moves like travelling, panning or zooming. Often such movement will go together with types of primary motion. Many games are built around secondary motion and the most common use of this type of motion is in the form of a long take, an uncut shot that is locked onto the protagonist and follows her from beginning till the end of a level. In mind come side-scrollers like Street Figher and Zaxxon, platform games like Super Mario Bros or Sonic The Hedgehog, RPGs like Diablo, and 3-D games like Tekken, Medal of Honor and Need for Speed. The reason for the long take being so popular is that it answers the player’s demand for control over her actions perfectly. This is also where visual narration in modern games differs significantly from that of cinema: Modern cinema and some of its major theories are in defense of montage, that is, tertiary motion types like the cut.

Secondary Motion (Camera Movement)

Tertiary motion types are very popular in constructing screen events in feature films. In contrast to primary and secondary motion, the motion created through tertiary motion is artificial and includes many shot transition types, such as the fade, the wipe, the A/B roll, and of course the cut, which I've already mentioned above. Most often tertiary motion is also used as a means of punctuation. Transitions from one scene to another, the beginning or end of an act are most often punctuated (or, if you wish, delineated) through types of tertiary motion.

The Use of Motion Types in Games

In terms of visual narration (or, the visual construction of screen events), many video games build their event-dense play sequences around primary and secondary motion types. This is due to tertiary motion types often being in conflict with the player’s need for control over her actions. Of course a lot of games will still make use of tertiary motion, but rarely ever does it happen that player control is sacrificed for visual spectatle achieved through tertiary motion types. Mostly it would be regarded as a design flaw.

In contrast to cinema, where shot variation and editing plays an important role in the construction of the screen event and in the management of the spectator’s experience density, many video game genres can be described as being the genres of the long take. We travel through the worlds of these games in one long, uncut shot, and rarely ever does it happen that we witness a cut or any other type of montage during sequences of high event density. In other words, it’s secondary motion that puts its mark on the narration and visual style in these video games. We’d see tertiary motion being preferred mostly to demarcate transition between levels, or as a way to jump to menu screens, but not so much during actual gameplay. [1]

Once we realize that tertiary motion is often in conflict with the player’s need for control and prefer to avoid it, we face some theoretical and practical problems when it comes to design camera behavior and environmental settings:

If our visualization options in constructing screen events are rather limited to primary and secondary motion, how can we still maintain high levels of experience density for the player?

What are our tools for punctuation and scene transitions if our basic visual narration style during actual gameplay is based on the long take and events are presented along a visual continuum?

How can we control pace and establish rhythm during actual gameplay, if the use of tertiary motion types is out of the question?

How can we delineate (make players comprehend the existence of) dramatic units such as ‘scenes’ in video games during a long take?

Rhythm and Pacing During Long Takes

Despite being bound to limited shot variation and montage options, we can make use of a wealth of methods of controlling pace and establishing rhythm in video games.

Camera Movement

What comes in mind first is of course a change in the pace and ‘aggressiveness’ of the camera’s movement itself. Switching between sequences in which the camera stands still and waits for us to move and sequences in which it simply drags us behind, is a way to control pace and establish rhythm in the uncut long shot. It’s simply the change in the parametres of the continuous camera movement that delineates events (or scenes), that creates pauses, and that establishes rhythm. An older example for designs that pace gameplay based on parametric changes during continuous camera movement would be side-scrolling shooters in which the camera drags us (or, the cross-hair that represents us) from one enemy hideout to another. Once the enemy appears, we shoot him over, only to be dragged to the next enemy’s hideout without any warning. A modern and very impressive example of such camera movement-based pacing and rhythm is God of War, a game which features a highly active and versatile moving camera.

Scale, Angle, Viewpoint, Figure-Ground Relations

The camera in God of War makes also use of switches in scale and angle during its continuous movement. Without breaking the visual continuum, it backs off to give a birdsview of the approaching war scene, it accelerates and drags the player behind to anticipate danger/action, it slows down and allows the player to move freely to signify a relatively safe section, and it up-closes and re-adjusts to the best scale and angle during the presentation of battle action, thereby also polishing and bringing to the foreground the ongoing primary motion in order to enhance spectacle and experience intensity. It is indeed such switching from figure to background, and back, that alone can establish a sense of rhythm.

Object movement

Even in games with a static frame, where not only tertiary, but also secondary motion is out of the question, we can still use object movement to change the pace and create rhytm. For instance in Centipede, the experience density increases when a spider comes along. First of all, the appearance of an additional moving object increases event density. There's more stuff to manage now. Second, the spider moves faster than all other objects and gets very close at us (no need to mention that a collision with it kills us immediately). Hence we feel an increase in pace when a spider appears. Once it has left the screen, however, we feel that we have returned to normal game pace. Hence rhythm is created. Another example is Pac-Man: In those section in which the roles are reversed and we can be a ghostbuster for a few seconds, we feel increased game pace. The ghosts move slow now (which feels like we've become faster) and there is limited time to catch them and get the reward. But soon it's us again who'll be the hunted and the pace will normalize. The switch between hunter and hunted roles creates rhythm.

Primary Motion-Secondary Motion Cycles

In a lot of games, we’d witness constant switching between object motion and camera motion as the long shot unfolds. This works in the following way: As we walk through safe sections, secondary motion rules. We walk, and the camera moves with us. Then, as we spot the enemy and engage with it, it is rather object movement that dominates the scene. Often the density of the attack means we’re getting stuck at that point and can only move on when the threat is eliminated, hence the camera wouldn’t move, but a lot of object motion would dominate the scene. An example for this is Diablo where during the walkthrough of a level the rhythmic structure consists of a constant switching between exploration/spotting (secondary motion) and ambush (primary motion): the monster attack nails us to a certain spot on the map and hence the camera seems to be locked on there; then, after we’ve killed the attackers and keep moving, the camera again starts to travel with us. Despite no use of tertiary motion, the result is controlled change in pace, which is just another name for rhythm.

Color and Lighting

Other visual parametres such as color and lighting can be used to signify scene delineation. Section with low gamma are followed by bright sections, cold colors are followed by warm colors, and all this establishes a feel of rhythm, or creates visually aided delineation of scenes.

The Tactile Dimension

An often ignored way of pacing and rhythm in video games is the tactile dimension of the fictional universe. This is a very important aspect in architectural design.[2] Change in the texture and feel of the space that we walk through has an impact on our perception and mood. A sequence of various tactile qualities will bring a series of changing moods with it and that can be used for pacing and rhythm. For instance the way our avatar slows down or accelerates while climbing or walking down a slope, while performing a rather unusal move like strafeing, or while wading through water or mud, all these are of a tactile nature. Our avatar would be still presented to us through secondary motion, but despite the continous long take that follows our actions, we would perceive a transition from one area to another, which would bring variation to the experience we have.

Sound and Ambience

Ambience is another issue that is very important. Transition from one set of natural sounds to another, switching between ‘noisy’ and ‘silent’ sequences, and even the way that our own noise sounds due to change in the tactile or acoustic dimension of the environment, all these can be used to establish a feeling of variation and rhythm along the long shot. For instance the sound of our footsteps would change depending on whether we walk on sand, or asphalt, or dry leaves. And sometimes this could demarcate that we’ve now entered a different chapter or scene in the level.

Volume, Shape, Form, Texture

Of course volume, form and shape are other important factors that architecture draws attention to: In racing games, delineation of sequences is partly achieved through the proportion of negative volumes to positive volumes: There’s for example the highway section, followed by the Chinatown section, followed by the claustrophobic tunnel section, and finally the traffic-plagued downtown section that we have to rush through before we reach the finish. Alone switching between a curvy sequence and a long straight will have an impact on pacing and rhythm.

Articulation of Event Chains

As we move through a level, we will witness how relatively safe and relatively dangerous sections keep replacing each other. The way in which their order is set up, is another important way to pace a level and create rhythm. In a game like Diablo, there would be sections in which enemies are always placed within each others line-of-sight, hence we would be forced into a killing spree because each new kill already triggers another monster coming at us. But the designers would make sure that after such a killing spree we have a pause. The next killing spree arrangement would be positioned a bit farther and wait for us to tap into it and trigger the new action section. Hence such an arrangement would create a break, a moment for resting. During our rest, we would re-assess our situation, re-arrange our inventory and make plans on what tactic or strategy to adopt next. Since all this would be presented along a single uncut shot, we would experience a feel of delineation that is being created without the use of tertiary motion.

Conclusion

In this article I have been dealing with an important design question: How can we control pace and establish rhythm under conditions of limited shot variation and montage options? As I tried to show, despite tertiary motion types not always being available to the game designer due to the risks they bear in regard to player control, there are many methods in pacing and giving rhythm to a game level that develops along the visual continuum of a long take.

Apart from criticism of 'trivial' themes in video games, maybe it is important to make film critics like Robert Ebert understand that the video game as an audio-visual medium cannot always make easily use of established cinematic visual conventions due to issues of player control. In many cases, tertiary motion types, which played an important role in cinema becoming a 'language' of artistic expression, will not be used in games. Hence, we come here accross a very important stylistic difference of the video game as an expressive medium. Critics like Ebert may not be so wrong in claiming that video games will never be like films, simply because these media draw back on different stylistic devices of the optic reservoir of moving images. But before we can claim that games never will be art, which is a totally different question, we must wait and see how game designers learn to deal better with conditions of limited shot variation and montage options.

Notes

[1] A few games like Asteroids or Joust can be said to make heavy use of tertiary motion in the form of cuts during actual gameplay. This happens in the form of a ‘jump’ to another slide, once our protagonist moves outside of the actual static frame.

[2] An art and science to find some clues on how to deal with game design issues during the use of long shots would be architecture. Architecture has to deal heavily with issues like circulation and spatial transition, that is, with structuring rhythmic and well-paced experiences for those who traverse spatial arrangements in one long uncut movement.

References

Francis D.K. Ching, Architecture: Form, Space, and Order

Herbert Zettl, Sight-Sound-Motion

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like