Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest 'Persuasive Games' column, author and game designer Ian Bogost looks at why we should repeal Bushnell's Law and move from 'addiction' to 'catchiness' in our framing of video games.

[In his latest 'Persuasive Games' column, author and game designer Ian Bogost looks at why we should repeal Bushnell's Law and move from 'addiction' to 'catchiness' in our framing of video games.]

Here's a game design aphorism you've surely heard before: a game, so it goes, ought to be "easy to learn and hard to master."

This axiom is so frequently repeated because it purports to hold the key to a powerful outcome: an addicting game, one people want to play over and over again once they've started, and in which starting is smooth and easy.

It's an adage most frequently applied to casual games, but it is also used to describe complex games of deep structure and emergent complexity.

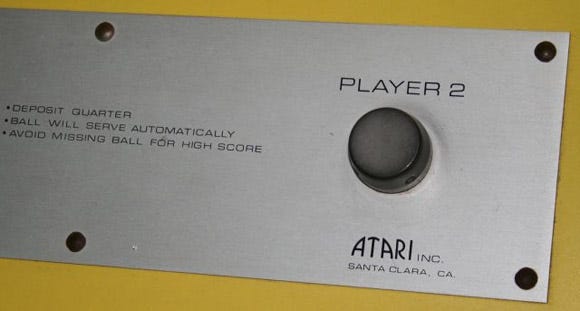

In the modern era, this familiar design guideline comes from coin-op. The aphorism is often attributed, in a slightly different form, to Atari founder Nolan Bushnell. In his honor, the concept has earned the title "Bushnell's Law" or "Nolan's Law":

"All the best games are easy to learn and difficult to master. They should reward the first quarter and the hundredth."

Bushnell learned this lesson first-hand when his first arcade cabinet Computer Space, a coin-op adaptation of the PDP-1 ur-videogame Space War, failed to become a commercial success.

Computer Space was complex, with two buttons for ship rotation, one for thrust, and another one for fire. While the same layout would eventually enjoy incredible success in the coin-op Asteroids, four identical buttons with different functions was too much for the arcade player of 1971.

Pong was supposedly inspired by this failure, a game so simple it could be taught in a single sentence: Avoid missing ball for high score. It seems so obvious, doesn't it? Games that are easy to start up the first time but also offer long-term appeal have the potential to become classics.

Except for one problem: the "easy to learn, hard to master" concept doesn't mean what you think it does.

Bushnell's eponymous law notwithstanding, the design values of quick pickup and long-term play surely didn't originate with him. Poker is another game that commonly enjoys the description. The same is true for classic board games like Go, Chess, and Othello.

Indeed, the famous board game inventor George Parker apparently adopted a different a version of Bushnell's Law way back in the late 19th century. From Philip Orbanes's history of Parker Bros.:

Each game must have an exciting, relevant theme and be easy enough for most people to understand. Finally, each game should be so sturdy that it could be played time and again, without wearing out.[1]

Note the subtle differences between Bushnell's take and Parker's. Parker isn't especially concerned with the learnability of a game, just that it deal with a familiar topic in a comprehensible way.

A century hence, time is more precious (or less revered), and simplifying the act of learning a game became Bushnell's focus. Still, something more complex than familiar controls or simple instructions is at work here.

Think about it: Pong isn't easy to learn, at all, for someone who has never played or seen racquet sports. Without a knowledge of such sports, the game would seem just as alien as a space battle around a black hole.

As it happens, table tennis became popular in Victorian England around the same time George Parker began creating games seriously. It offered an indoor version of tennis, a popular lawn sport among the upper-class, played with ad-hoc accoutrements in libraries or conservatories.

Both ordinary tennis and its indoor table variety had enjoyed over a century of continuous practice by the time Bushnell and Atari engineer Al Alcorn popularized their videogame adaptation of the sport (itself a revision of two earlier efforts, Willy Higginbotham's Tennis for Two and Ralph Baer's "Brown Box").

Pong offers quick pick-up not because it is easier to learn than Computer Space (although that was also true), but because it draws on familiar conventions from that sport. Or better, Pong is "easy to learn" precisely because it assumes the basic rules and function of a familiar cultural practice.

Familiarity is thus the primary property of the game, not learnability; it is familiarity that makes something easy to learn. It is what makes "Avoid missing ball" make any sense in the first place.

[1] Philip E. Orbanes, The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers, from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit, (Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press, 2003), p. 13. I am grateful to Jesper Juul for bringing this passage to my attention.

Wii Sports offers a similar lesson. The broad success of the Wii console comes in no small part from the effectiveness of this launch title. Wii Sports is really just Pong warmed over, offering simple abstractions of well-known sports that are themselves quite complex to learn, but which large populations have managed to understand over time.

What about so-called casual games? Tetris isn't really easy to learn either. Sure, it offers simple controls and a comprehensible goal, but nothing about those controls or that goal is obvious or intuitive; they are not inherently familiar ideas.

But the tetrominoes, those are familiar. Tile games find their roots in dominoes, an ancient game, one millennia old in its earliest forms.

Polyominoes (a shape made of a certain number of connected squares; Tetris pieces use four) have been common elements of puzzles since the early 20th century, most frequently found in tiling puzzles (like pentominoes) or assembly puzzles (like tangrams).

Tetris cleverly combines both the assembly and the tiling varieties of polyomino puzzles, asking the player to construct a small sub-tiled region (a line) by making micro-assemblies of two or three blocks.

As all of these examples suggest, familiarity builds on prior conventions. Pong builds upon table tennis, which builds upon tennis, which builds upon racquets. Tetris builds upon pentominoes, which builds upon dominoes, which builds upon early games of dice and bones.

Games can also produce their own conventions, which become familiar enough to be adopted later in the same way that Pong adopts table tennis. The falling tetrominoes of Tetris, for example, inspire the falling blocks of Columns or Dr. Mario or Klax -- games that make modifications to familiar conventions from earlier games as they congeal.

Likewise, the familiarity of subjects helps apologize for unfamiliarity of form. George Parker's early game Banking (1883) built upon players' basic knowledge of financial practices. Popular casual games in the vein of Diner Dash do the same, relying on player's familiarity with waitressing, hairdressing, or other professions.

No matter the case, the result is important: the maxim "easy to learn" is misunderstood. Mechanical simplicity is less important than conceptual familiarity.

So much for "easy to use." What about "hard to master?"

Some games are profound enough to deserve the provocation toward mastery, but not many. Chess and Go do by virtue of complexity and emergence: they are games that offer such rich and intricate variation that only careful, long-term study can produce proficiency.

This is why the concept of a "chess master" means something more than simply someone who just plays a lot. Chess and Go are games for which mastery is definitively "hard."

In her GDC 2009 microtalk, Tracy Fullerton observed that the very hard mastery of such games inspires less able players by tracing the edges of the game's beauty. We might call this the terrain of sublime mastery. And there is indeed a fearful wonder in this territory. But it is also a weird mastery, one that sits at the fringes of a game, alienating as much as it inspires.

The standard rationale for mastery makes appeals to the depth of a game, suggesting that the value of its design cannot be expended in only a few sessions, but would require innumerable replays, perhaps theoretically infinite ones, to reveal all its secrets. The problem is, sublime mastery is usually desirable only as an ideal, not as an experience.

It's no secret that Nolan Bushnell was a fan of Go. Atari, after all, is a technical term from that game.

It's no secret that Nolan Bushnell was a fan of Go. Atari, after all, is a technical term from that game.

So it is easy to assume that the "difficult to master" portion of Bushnell's Law refers to NP-hard problems of the Go variety. But the second portion of his proverb suggests a different meaning.

That a game should "reward the first quarter as well as the hundredth" (this was the era of the coin-op) suggests nothing about the cosmic intricacy of a game like Go.

Instead, it suggests that a game ought to produce allure many times. Bushnell's Law makes no claim about the kind of appeal a game ought to make on the tenth or hundredth playing, nor if that allure ought to be entirely different or new every time.

Likewise, George Parker's design techniques make no claims about mastery either. He does, however, clarify one sort of appeal a game might offer over time.

Parker is concerned with material, not conceptual durability when he says that a game should be able to be played time and time again.

While such resilience does imply some reason to want to play again, it does not imply any kind of invitation toward mastery whatsoever, whether practical or sublime.

The allure of the game must simply inspire multiple plays, not necessarily multiple unique plays, or multiple plays approaching an ideal.

As Philip Orbanes explains, Parker Bros. valued durability. "Make it last" became a company creed.

Indeed, the matter of quality of material and manufacture helped make Parker Bros. games appealing as artifacts, not just as games.

Like any craft, a board or card game can create different levels of physical attachment. The design of Monopoly, with its modernist typography, winsome illustrations, and forged tokens create a game of material appeal, one that produces pleasure in the holding, viewing, and possessing as well as in the playing.

Monopoly becomes a place we want to go back to, just as does Rapture or Azeroth. The fact that we can enjoy arguing over who gets to be the car or the dog in a game of Monopoly is just as important -- if not moreso -- than the appeal of the game's mechanics (which indeed are far more rapidly exhausted than those of Go).

Similarly, Pong does not reward the hundredth quarter through emergent complexity. Instead, it rewards that quarter through social context. In the 1970s, remember, coin-ops were mostly found in places like bars and bowling alleys, and indeed the game borrowed very same context that makes tavern games like darts and pool appealing: one can play them with friends while drinking.

Sure, one can get better at Pong like one can get better at Eight Ball, but the real purpose of these games is to offer a chance to commune with (or mock) one's mates over brews.

Most people don't really care if they master Pong or pool -- or Tetris or Chess for that matter.

Instead, people like to be conversant in these games so that they can incorporate them into various practices, moving beyond the phase of learning the basics and on to the phase of using the games for purposes beyond their mechanics alone.

Indeed, idealizing the sublime mastery of the sort the Chess master or pool shark pursues may even serve an undesirable characteristic for ordinary players.

In 1906, the New York Times reported a precipitous decline in the popularity of racquets, predicting its inevitable supplantation by squash, thanks to the latter's cheaper cost and easier mastery. Said Peter Latham, then 18-year champion of the sport, "Racquets is far more difficult to master than squash or court tennis. I think racquets will remain where it is, while squash will continue to grow in popularity."[2]

Contrary to popular belief, the examples of racquets and squash suggest that a low, rather than a high-ceiling to mastery might offer greater rather than less appeal. As in the case of Chess or Go, the relative difficulty of the former sport made it seem inaccessible rather than appealing.

That's great for early 20th century indoor sports, but what does it matter for 21st century videogames?

Consider a casual downloadable game like Zuma. Like many casual games, Zuma offers a free trial, in this case one that is three levels long.

Consider a casual downloadable game like Zuma. Like many casual games, Zuma offers a free trial, in this case one that is three levels long.

It's a well-known fact that games of this sort suffer from a low (1-3%) conversion rate from trial downloads to full purchases.

One conclusion we can draw from such figures is this: the Zuma trial offers enough habituation to serve a gratifying purpose for most players.

Becoming adept at the three or so levels of Zuma's trial requires limited skill, drive, or persistence. It's inevitable, really. The demo is gratifying enough as it is, habituating players toward a certain level of performance they are able to accomplish easily.

This is not mastery, at all; in the case of Zuma, the habitual activity of repeated play is likely to relate to biding time or zoning out more than it is to encourage increased performance. Arguably, the same is true for Tetris -- imagine a "free demo level" of the latter game. Who would really need anything more?

Given their numerical scores, highscore lists, achievements, and myriad other ways to measure performance tangibly, it's true that videogames, board games, tavern games, and sports sometimes do invite us to pursue certain accomplishments.

But more frequently, we feel compelled to return to games that we have habituated ourselves toward for other reasons. Airport Mania lets us play air traffic controller for a few minutes. Tetris affords a feeling of control and organization in a world of entropy.

Like "easy to learn," "hard to master" turns out to be a rare secondary property of games, one most frequently left for the pro ballplayers, chess masters, and card sharks -- all specialists, not generalists as the casual games lore would have us believe.

[2] New York Times, "Decline of Racquets as an Indoor Sport," January 4, 1906. Thanks again to Jesper Juul for bringing this example to my attention.

Here's a suprising notion that might explain both familiarity and habituation in games: catchiness.

Think about a catchy song, the kind you can't get out of your head when you hear it. How does that happen? The reason songs stick with us is unclear, but some researchers have called it a "cognitive itch," a stimulus that creates a missing idea that our brains can't help but fill in.[3] Whether the brain science is true or not isn't really important; it offers a helpful metaphor through which to pose another question: what causes the itch?

Paul Barsom, a Penn State professor of music composition, suggests several factors that seem to aid in making a song catchy. Conveniently, they correspond well to my re-reading of Bushnell's Law above.

One is familiarity. Says Barsom, "A certain familiarity -- similarity to music one already knows -- can play a role [in making a song catchy]. Unfamiliar music doesn't connect well."

It makes sense: the effort required to grasp a new musical concept, genre, or approach makes the higher-order work of just feeling the music hard to access.

Familiarity relates to another of Barsom's observations: repetition. Catchy songs often have a "hook," a musical phrase where the majority of the catchy payload resides. Indeed, the itch usually lasts only a few bars, sometimes annoyingly so.

But games rely on small atoms of interaction even more so than do songs. The catchy part of a game repeats more innately than does a song's chorus. In Tetris it's the fitting together of tetrominoes. In Diner Dash it's the gratification of servicing a customer. In Drop7 its the mental calculation of a stone's position. It is also in such tiny refrains where these and other catchy games revisit familiar conventions.

Another property is what Barsom calls a "cultural connection." When a song attaches itself to an external concept, sensation, or idea, it seems to increase its ability to become catchy.

The Beach Boys' catchy songs connected new-found ideas of summer and beach life to more complex themes of longing and desire. When Katy Perry sings about kissing a girl in the same year that witnesses controversial legislation about gay rights, she creates a less charged mental space for mulling over such questions.

Cultural connections help habituate ideas. They give them form, acclimatizing listeners -- or players -- to the social contexts in which ideas might be used. In 1972, Pong introduced the world to the idea that computers were about to become machines for exploring ideas and interacting with people. In 2006, Wii Sports reactivated the den as a social space for families, recuperating the lost digital hearth of the Atari/Intellivision era.

With music, we embody catchiness by running a song over in our heads or tapping a foot. With games, we embody catchiness by playing again, for specific reasons.

Isn't "catchiness" a much better verbal frame than "compulsion" or "addiction" for the kinds of positive feelings of homecoming many games offer? Game designers talk openly about how to make their games "more addicting"; Viacom even operates a game portal called AddictingGames.

Why would anyone choose to call their craft "addicting," a descriptor we normally reserve for unpopular corporeal sins like nicotine? Why would we want game design to sound like drug dealing, the first "easy to use" hit opening a guileful Pandora's box of "hard mastery?"

The rhetorical benefits of "catchiness" alone suggest its adoption. Wouldn't you rather tell your mother that "Drop7 is a really catchy game," instead of comparing it implicitly to a narcotic?

But moreso, I don't think most game designers really want to make games that are "easy to learn and hard to master." A game that's easy to learn probably isn't a bad thing, but it doesn't get at the heart of the sort of appeal that leads to catchiness.

We have plenty of games that are hard to master, and they are not the that ones normally earn the label of "casual." Metal Gear Solid is hard to master. So is Spelunky. Ditto Ninja Gaiden. Striving for a design that demands mastery isn't bad, it's just that it's not the goal served by the designs that adopt Bushnell's Law.

Mastery is a very specialized carrot that works only in extreme circumstances; indeed, the ludic sublime is probably a very rare terrain. Most of the time, creating habituation is enough: making players want to come back to visit your game, whether or not they want to eke out every morsel of performance from the thing.

So, let's end the era of Bushnell's Law, not because it's useless or base, but because it's wrong. It doesn't explain the phenomenon we have assumed it does. Or more precisely, let's excise the first half, and keep the rest: A game should reward the first play and the hundredth.

How? By culturing familiarity and constructing a habitual experience. By finding receptors for familiar mechanics and tuning them slightly differently, so as to make those receptors resonate in a new way, and then coupling those new resonances with meaningful ideas, practices, or experiences.

By becoming catchy, appealing, memorable, a willing, conscious part of the texture of a player's broader life.

[3] Cf. David J.M. Kramer et al., "Musical imagery: Sound of silence activates auditory cortex," Nature 434, 158 (10 March 2005).

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like