Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest Persuasive Games column, Ian Bogost argues that what the industry needs right now is "games that would demystify the medium", citing clothing designer Marc Ecko's "insightful and ironic" observations - and how does this apply to serious games?

Fashion mogul Marc Ecko’s eponymous clothing company now brings in $1 billion a year in revenue.1 Recently, Ecko has branched out from rhino-emblazoned t-shirts, shoes, and underpants to popular media, including the consumer culture rag Complex Magazine, the extreme lifestyle YouTube knock-off eckotv.com, and the 2006 video game Mark Ecko’s Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure.

Recently, a canned interview with Ecko ran in popular magazines like Wired, paid for by financial consultants CIT Group.2 It’s one of those “Special Advertising Sections” designed to integrate so seamlessly into the magazine that it’s easy to mistake it for editorial content. In the interview, Ecko explains “What’s next” for his growing media conglomerate:

I want to keep growing in the video-gaming space. I believe it’s the Wild West of media culture. There’s something magical and abstract about gaming. Games aren’t yet demystified — versus movies, for example; there are TV shows about the making of movies.

Ecko’s point is both insightful and ironic. It contains a rather complex observation about the current state of video games as a medium: television is so familiar, it’s not even startling to think about television programming produced solely to discuss other media forms.

The same could not even be imagined of video games. The form of the insight reiterates Ecko’s point: his comments appear as a paid advertisement simulating a magazine interview, an absurd situation that is nevertheless completely legible to the millions of magazine readers whose eyes will pass over it. Magazines and television are just too mundane, too boring for these things to be very surprising.

Marc Ecko is not interested in the mundane; his sights are firmly set on the flashier side of the medium he already began to explore in Getting Up, itself a critically underappreciated game that hides a critique of an autocratic police state in a game about graffiti.3 But we can turn his observation on its head and use it to find an omission in the industry’s vision for the future of video games: demystification is a possible design goal for game developers.

The commercial game industry largely strives for Hollywood blockbuster-style spectacles. The fledgling indie game scene often privileges new gameplay mechanics or subjects for games, but just as frequently it showcases the hopeful yet derivative swing of so many minor-leaguers trying to break into the majors. Despite major differences, both efforts trace the earnest hope that video games are an expressive medium as important as film or literature, but different in form.

But few developers set their sights on a lower-hanging, if more bitter fruit: games that would demystify the medium, to use Ecko’s words. Literature and film are indeed media in the service of art, but they are also media in the service of much more mundane goals. Consider everything that is possible to do with film.

For one part, we can use moving images to discover the nature of human experience, like the exploration of bitterness and compassion in Casablanca. For another part, we can use moving images to document our ordinary lives, as in a home movie of a child’s birthday party to be shared with (or more likely archived for) one’s extended family. For yet another part, we can use moving images to explain ordinary phenomena, like the operation of the seat belt in an airplane safety video. As expressive artifacts, Casablanca, the home movie, and the airplane safety video have very little in common. But as media artifacts, they have many things in common, in terms of the filmic techniques used to capture and project moving images.

In fact, the birthday party and airplane safety videos would both be impossible without the long history of film as a medium of documentation and expression that preceded them. But the banality of these later examples also increases the total attention we pay as a culture to moving images in the first place. We see films all around us, in many different contexts, and this makes film in general more comprehensible as a medium.

Very few video games set out to tackle mundane applications akin to the home movie or the airplane safety video. And really, is it very surprising? Who would set their sights on these mundane aspects of human experience, things that recede into the background, given the glitzy alternative of commercial games?

Serious games offer one example. These are games whose mission includes applications of video games outside the sphere of entertainment. These are games that train soliders and corporate employees, educate middle-schoolers and technology certification hopefuls, help diabetics manage their blood sugar, try to persuade consumers to purchase products and services.

Serious games offer one example. These are games whose mission includes applications of video games outside the sphere of entertainment. These are games that train soliders and corporate employees, educate middle-schoolers and technology certification hopefuls, help diabetics manage their blood sugar, try to persuade consumers to purchase products and services.

Certainly many of these activities seem to be just as banal as pointing out the exits on a Boeing 767. Serious games thus have an important role to serve in video games’ attempts to mature as a medium—not because they train or educate or inform, but because they help make games more boring.

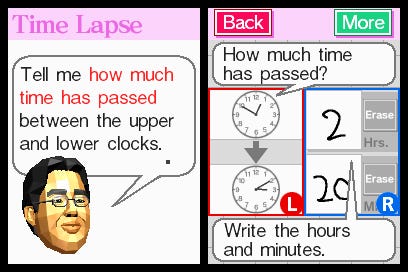

Then consider Nintendo’s popular Brain Age for the Nintendo DS, along with all of its sequels and knock-offs. Brain Age has been celebrated not only as a tremendous commercial success, but also a contributor toward making games more appealing to a broader audience. In his keynote at the 2007 Game Developers Conference, Shigeru Miyamoto even suggested that Brain Age was largely responsible for drawing his wife into games.

But why is Brain Age a success of this kind? It’s certainly a very different kind of game from Halo or even Miyamoto’s own Zelda series, games that allow the player to inhabit complex fantasy worlds. Instead, much of Brain Age’s success seems to come precisely from the ordinariness of its demands.

It is a game of chores, really, not of challenges. Games like speed arithmetic and number tracing actually become maddeningly dull after only a short time, but many players persist because they want to have the sensation of keeping their minds sharp. We use Brain Age like we might use an exercise video, or a bathroom book of aphorisms, or a low-carb cookbook. Whether or not the game really contributes to long-term mental health is irrelevant; it makes people feel as though they are improving their long term mental health. It satisfies a mundane need for personal upkeep.

As a medium becomes more familiar, it also becomes less edgy and exciting. This is what Marc Ecko means when he refers to movies as demystified. Over time, media becomes domesticated, and domestication is a mixed blessing.

On the one hand, it allows broader reach and scale. It means that more people can understand and manipulate the medium. Grandma and grandpa understand what they are looking at when you send them a VHS tape of junior blowing out the candles. On the other hand, it makes once a exotic, wild medium tame. After all, how many of you actually watch those airplane safety videos? Would you play an airplane safety game on the seatback monitor? Would you play it after seeing it on every flight for the next ten years?

Some proponents of serious games have unfortunately suggested that such games are opposed to the commercial, entertainment games that have come to define popular opinion of the medium. If we think of the possibility space for games as a more complex, graduated one, in which many kinds of experiences could be touched by games, then many more kinds of innovation present themselves.

And if we think of every point along this design gradient as an opportunity to be exploited, then we should want games to be more boring. Not just some games, we should want many of them, maybe even most of them to be boring, so that the ones that are not can become the Casablancas of our future medium.

1 http://www.marceckoenterprises.com/facts/facts.shtml.

2 For example, Wired 15.5, May 2007, pp. 41-44.

3 For more on this, see Stephen Totilo’s review of the game on MTV News: http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1504962/20050629/index.jhtml?headlines=true.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like