Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Atsushi Inaba, co-founder of Platinum Games (The Wonderful 101, Bayonetta, Transformers: Devastation) shares his insight on how to make world-class action games.

Atsushi Inaba is a co-founder of Platinum Games (The Wonderful 101, Bayonetta, Transformers: Devastation.) His job is to oversee all of the company's games "from the moment a project is kicked off until completion," he said, by way of introducing himself in his GDC session.

He started with a surprising definition of what an "action game" is.

When it comes to the game design, they're passive, he says. "It's a set of actions responding to output. You might be wondering what 'output' means," said Inaba. "Output refers to situation such as the enemy appearing right in front of you, or you being attacked."

"For example, attacking an enemy because it appeared in front of me, or dodging a bullet because the enemy attacking you, these actions are reactive moves taken against the output. Something happened, and you reacted to it."

"And although the impression one gets from the term 'action games' sounds like a genre where you are proactively doing something at will, it actually is not -- there's something that happens first and you must react to it in a certain window of time."

They're inherently reactive; horror and adventure games, where the player explores the world, put the player in the active role, conversely: "They are fundamentally the opposite," he said.

There's a challenge for the developer, though: "If these actions go on for a long time or the window is so short, the game becomes more difficult." Inaba said that Platinum is very careful about this sort of thing -- and also about game pacing, a topic he discussed at length.

You need "unique selling points" -- as in Bayonetta, it's Witch Time, the game's slowed-down time mode. A pro designer should be able to come up with three good ideas, Inaba said.

Then there are features which expand the game, such as character unlocks. "It opens things up in a very lateral way."

Then there's depth: "It's not easy to give an example. A combo system is one," Inaba said. These are gameplay systems that require mastery to engage with fully.

"Core gamers aren't the only ones who play action games so it's necessary to make sure players of different levels can enjoy your game," Inaba cautioned. "It's important to widen the entry point of your game, but you also have to make sure that those who play straight through the path enjoy the experience." Depth, he said, is equally important.

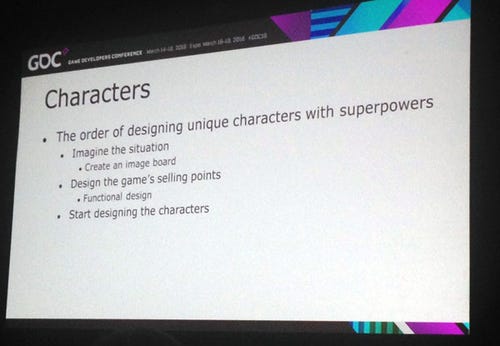

Designers tend to want to create skills and abilities for characters and build a game around those, but this "does not come first," Inaba said.

As action games are passive, the most important question for a designer is: "What kinds of situations do I want the player to face, and what are they going to do?"

"You need the ability to imagine them in your head," said Inaba. "First come up with that unexpected situation, then an unexpected or surprise ability or power to get through the situation. ... You need to be able to imagine that flow from the beginning to end."

To that end, Platinum Games does not use much in the way of design documents: "It's fundamentally impossible to write a concept or design document on the unique selling points for action games," he said.

He also recommends roping in team members off the design team, like programmers or artists, to come up with game ideas: "We just tell them, 'To make it fun and interesting, surprise us. Tell us your ideas. Show us what you got.' ... To enjoy and appreciate one's individuality and these ideas that come from different sections is part of the fun of making a game on a team."

Functional design becomes a real danger when working on sequels: "The majority of people will unconsciously use this as a basis. Taking an element that was well received in a previous game and upgrading it, or giving it a boost, is a no-brainer."

"However that's not how it works. As I said earlier, the priority should be on designing the situations first. If a functionality is designed to capitalize on that situation, then that's great. It's really easy to fall into a trap on a series."

And if you rely too much on players knowing the mechanics of the first game, "you run a risk of becoming niche."

"Games are supposed to be fun. That is the basis of the game," said Inaba. But many games force replay value (with padding, or grinding, or unlocking.)

"What is the replay value in action games? It's really about improving the player's skills. I'm not talking about unlocking skills in game, but actually improving his or her skills," he said.

But even with that in mind, always remember the players who will only play the game one time on the basic difficulty level: "it's important for those players to have the best experience," too, he said.

"We create situations where we take those players to levels beyond their own expectations," Inaba said. "Therefore we need stages or gimmicks, or combat situations made just for those opportunities. It's really a luxury for action games, they need to be fun and enjoyable even if you play it only once."

Platinum's games have distinct and memorable main characters -- none so much as Bayonetta. "The purer the action game, the higher the need for a really original and unique main character," said Inaba.

"This is the correct order" to design a character in, said Inaba, referring to the above slide. "In other words, the core of what you want the players to experience and the character art design are in a very long, linear relationship."

When it comes to story, meanwhile, all you need is a basic motivation. Inaba said that a premise as simple as that of Super Mario Bros. -- "Peach is kidnapped, go rescue her" -- is ideal.

Of course, Platinum's Bayonetta and The Wonderful 101, in particular, are very story-heavy games. When creating an action game's story, then, "The approach becomes how to connect the previous situation to the next situation. Which means you aren't able to create an action game by writing the whole story first," Inaba said.

He gave the example of Mad World, one of the company's earlier games (for the Wii.) It's an incredibly violent game, and engaging in violence is the motivation for the player; but "it would make the player disgusted toward themselves and toward the game" if it stopped there, Inaba said. The story of the game -- as a justification for its setting, "this crazy world where the only choice is to be violent" -- was developed in parallel with the game design itself.

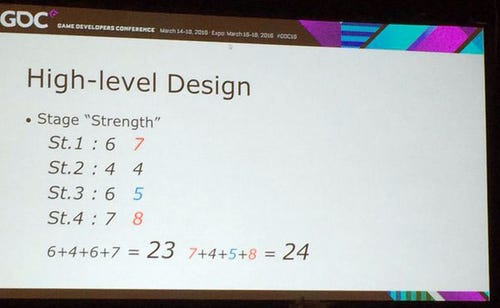

Since Inaba oversees all of Platinum's games, he emphasized something he calls "high-level design" -- a zoomed-out view of the games: "it's really about the overall flow and progression on a larger scale. What we want the players to experience as a whole."

Here's the crucial takeaway: Constant excitement becomes numbing. Players will get tired if games continually ramp up. "Let's think about what to do to avoid that situation," he said. The good news is that if you carefully tune the intensity of the game at a high level, you will get a much more favortable result.

In the slide above, Stage 1 is tuned to a "6" for intensity, but because the game has just begun, the player perceives it as a "7." But Stage 2 ratchets down the intensity to a 4 -- and it feels that way to the player. For Stage 3, it's just as intense as Stage 1, but the player is used to the game now, so it doesn't feel quite as intense. But ramping up again for Stage 4, you get an interesting effect: The player finds it more intense.

This is an "oversimplification" for the purposes of a GDC talk, Inaba admitted, but it gets the point across.

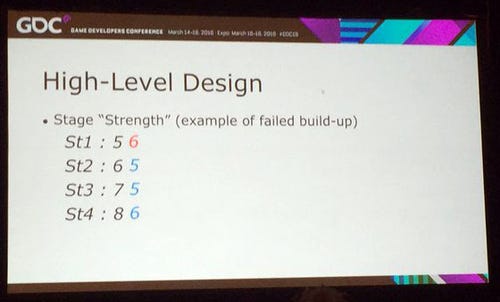

Here's the thing: If you just do a linear ramp, you'll end up with this:

A stage flow that's less than the sum of its total, and which feels stagnant to the player. "It can easily turn out to be a disaster" if you try to continuously ramp up a game's intensity without knowing what you're doing, he said.

Read more about:

event-gdcYou May Also Like