Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Greg Buchanan, writer of the No Man's Sky campaign Atlas Rises and other games including his own American Election, shares his thoughts on writing for open world and linear games.

Being a writer for video games requires versatility, not just in subject matter but also in structure. Sometimes a writer might need to be able to tell a story that unfolds over time, in a straight line. Other times, a writer must string a coherent story together in a procedurally-generated world where every playthrough unravels a new, unique story shaped by a player. There are countless other ways in which game writers stretch their talents in order to meet the broader needs of a specific game.

Greg Buchanan is one of these versatile writers. He's a freelance scriptwriter for games in indie and triple-A spaces, in addition to being a writer of novels and comics. He wrote the campaign No Man's Sky: Atlas Rises for Hello Games, in addition to having writing credits on Metro: Exodus from 4A Games, the recently-released No Man's Sky: NEXT, and his own game, American Election among others.

“The challenge of writing anything -- of coming up with convincing, emotional, fictional worlds and stories full of people -- is figuring out how to get in the right frame of mind to generate good productive imaginative material," he said in an interview with Gamasutra.

"The way the games industry operates can complicate this a great deal," he said. "For one of my own projects or for script work in other [non-game] media, I’ll work wherever I want, however I want: I’ll go to cafes, museums, restaurants, beaches, parks, whatever produces a different response from my brain and creates an imaginative leap.”

No Man's Sky: Atlas Rises

But Buchanan's process for video game work is different. He's worked on some big titles, some of which he joined late in development, which requires an adjusted approach to writing. “I like to try and figure out likely gameplay emotions on the part of players -- how engaging in the game’s mechanics might feel -- and weaving these emotions through my story, sometimes maybe even complicating or opposing them," he said.

"There’s this big phrase in game writing -- ‘ludonarrative dissonance’ -- which, essentially, refers to a conflict between gameplay and story.” Buchanan gave the example of a game where you are depicted as a noble hero in cutscenes, only to be encouraged to run around murdering everything just to level up in the game itself.

“However, although ludonarrative dissonance is often seen as some major problem with games, I find dissonance and its potential quite fascinating, even inevitable. As long as you’re conscious of what you’re doing, you can encourage, complicate, and twist player emotions really effectively in some titles in order to create deeply meaningful experiences.”

Beyond problems of fitting themes and gameplay, certain kinds of games can complicate a writer’s job substantially, especially open world or even larger-scale open-universe games where players can choose their own paths.

“You can’t necessarily mandate a specific sequence of story elements being encountered or even define what those story elements will look like contextually,” he said. "So you have to not only figure out various possible routes that you might account for (with a reasonable degree of probability), but often generate much more content to account for the expectation by the player of random discovery and a limitless, vast world.”

Most games do offer the option for players to skip over text or cutscenes -- it's virtually standard practice. Being a multi-faceted medium with sound, visuals and interactivity, video games offer a multitude of distractions that can draw a player away from a game's writing. For Buchanan, that's just the reality of the medium, and game writers need to adapt.

“We have to convince people to give a shit, and that’s a lot of what good game writing is about, on the level of overarching design as well as the writing of individual lines," he said. "All writing should be about this to some extent -- but in games, the frequent mechanical ability to skip cutscenes and not gameplay says it all. Our task to win the audience’s attention is, to some extent, more difficult in this medium than elsewhere.”

When it comes to games that are more linear, he emphasizes they “aren’t as similar to film storytelling as people think. People feel like linear games should fit classic dramatic principles, like three-act structure or the hero’s journey, and while players recognize these patterns to some extent, it’s not possible to 1:1 match older storytelling forms to games.”

He adds, “You have to think about the episodic nature of game storytelling -- how narrative-explicit elements such as cutscenes are rarely continuous but book-end bursts of gameplay -- and think about how to take advantage of the unique opportunities of the gameplay and narrative framing at hand.”

Buchanan's GDC 2019 talk

Buchanan uses the example of Final Fantasy VII -- it has long periods where you stop focusing on the story in favor of hunting down the next level or materia. This all adds to and continues to tell your story, but there’s a clear difference between this kind of narrative and that of a film, even if films have action sequences as well.

When it comes to game stories that are more open world in structure, Buchanan explains how players' brains make sense of disjointed stories, which is an important concept for game writers to understand.

“Even if you, say, dismantled a book’s chapters and gave them to someone in a random sequence, readers interpret the sequence they’re giving as having some kind of intentionality to it, judging both the characters and the author behind it in different ways depending on that random sequence,” he said. Even if open world games offer a huge range of choices that affect the story you follow, we still feel like the sequence of our encounters means something.

In games, however, as opposed to randomly dismantled books such as B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates, you can actually track the route players take and adjust for it. Buchanan uses the example of a popular voice-controlled Alexa sci-fi game he wrote, The Vortex, where after an initial linear section, you get to choose where to send your team of robots first.

“You’ll find out mysteries and secrets of the past in different sequences, and the job of a writer in this kind of scenario is to make each route as dramatically satisfying as the other," he said. "Finding out a character is a murderer before you see a scene of that character at a birthday party is bound to affect the way you view things.”

Buchanan has just released a new indie game American Election, about a campaign assistant working to elect a new President of the United States. In addition to this, he recently announced a book deal with Macmillan for his upcoming literary thriller novel Sixteen Horses.

When asked about these moves away from work-for-hire and how he views writing for games after a few years in the industry, he said, “I am really proud of my work and collaboration with other developers -- seeing the reviews and the way players have responded to stuff like the No Man’s Sky: Atlas Rises story and my other work has been amazing to see. I have learned so much from working with others and intend to keep doing so, particularly on more experimental titles and for newer platforms.”

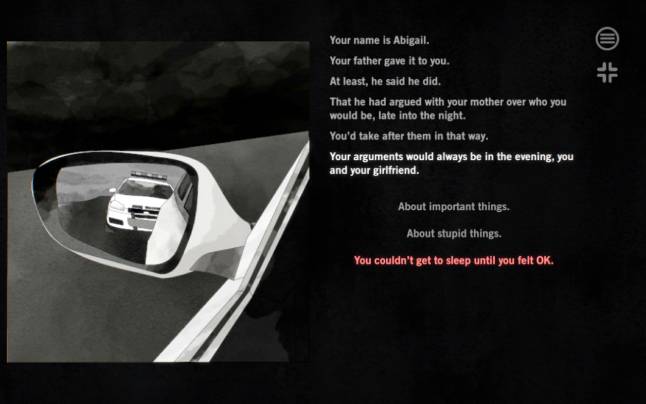

American Election

At the same time, Buchanan says he is finding it incredibly rewarding to steer the ship on his own games with titles like American Election and his upcoming indie horror game The God In White. In addition to this, he is producing a series of articles designed to help newcomers to the industry navigate the way towards getting jobs and learning more about writing and narrative design.

Buchanan said getting a start in a career as a games writer is as simple as doing the work. “It sounds really basic, but actually make a game," he said. "Use Twine or Ink or any other number of tools out there and just make something ten minutes long. It doesn’t matter if it’s good, it doesn’t matter if it’s what you’ve dreamed about -- you will have done more than many who have this dream. You will have started the journey.”

You May Also Like