Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Fans of interactive fiction have lots to be excited about with this year's IGF. We catch up with Tender Claws, creators of Excellence in Narrative nominee PRY, a storytelling game with a unique interface.

For fans of interactive fiction games, this might be one of the best Independent Games Festival showings in some time -- there are a few games nominated that experiment with platform and interface in storytelling games.

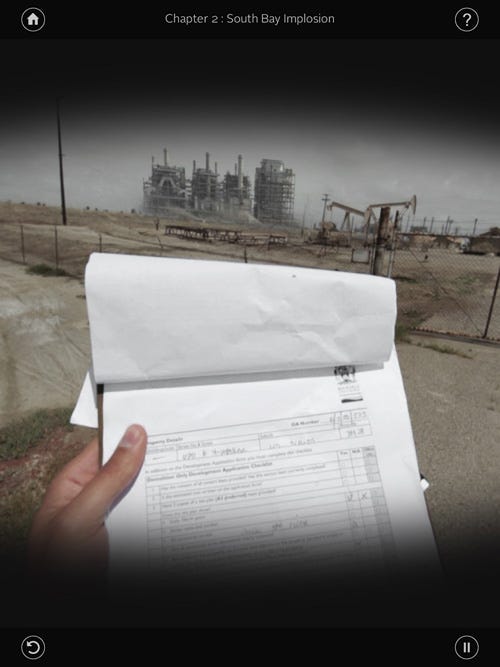

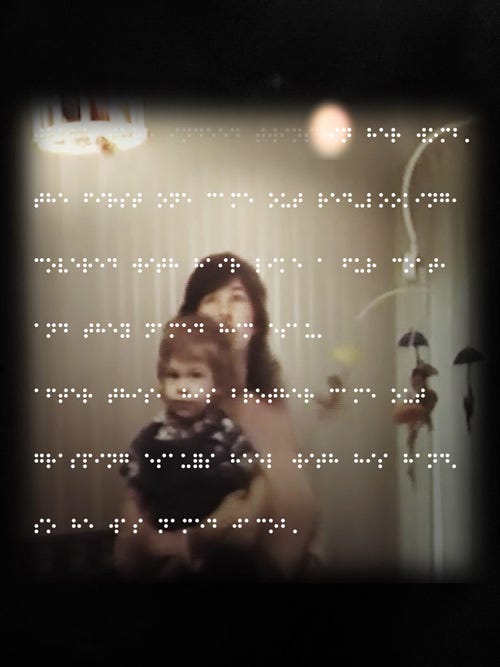

Tender Claws' PRY, up for Excellence in Narrative, is one such title, tasking players with exploring the mind of a demolitions expert following the Gulf War. The way players touch, pinch and pull the tablet changes the way they experience the story, making for a complex, visually sophisticated, and unique interactive reading experience. As part of our ongoing series of interviews with IGF nominees, we asked Tender Claws' Samantha Gorman and Danny Cannizzaro all about the project.

What's your background in game development, and what inspired you to create PRY?

As makers, we love playing games! Playing games inspires us to dream about what we would like to make and see in the future. Before founding Tender Claws, Danny worked as an interactive art director at companies that made experimental and playful digital experiences. Samantha is a writer that specializes in composing for hybrid digital spaces. We also enjoy gaming beyond the digital. One of our physical games, Tumball, (a 2v2 competitive sport played with leaf blowers and tumbleweeds) was a finalist at IndieCade in 2014.

We are always thinking about issues at the intersection of interactivity, story and text. Why engage, why interact in a specific way? PRY came out of these questions. We want to create gameplay interactions/interfaces where the form directly ties to the content or story a player experiences. For example, when our character (an unreliable narrator) is telling the story of events he witnessed, the player can pry apart the lines of his thoughts to reveal deeper layers that may counter or go back on what he has previously said.

Our process mandates developing gameplay, story and technology simultaneously so they all inform each other's evolution (so no one element feels like an add-on or afterthought). Part of the fun of creating games is getting to be a collage artist. We also love to work between genres. How can books, cinema, and games learn from and enhance each other?

What tools did you use?

We coded PRY in Objective C. Because of the large amount of video content playing simultaneously, we chose to use the native language rather than a third-party game engine like Unity. Danny taught himself to code for this project using iTunes U courses. We’ve always found it’s a lot easier to learn technical skills when it's for specific projects that we’re excited about.

From there, we drew on our experience with video and writing for media. We filmed all the content with DSLRs and GoPros for the underwater shots (a "Part 2" hint). We organized ourselves with extensive Google Docs that barely opened because of comment overload. We would like to eventually build an editor on our framework so people can write their own stories in this way.

How long did you spend working on the game?

We began PRY as a small studio of two people who did pretty much everything you see from coding, to filming, writing, sound, etc. PRY probably took us the better part of two and half years, with lots of experimentation, visions, and revisions.

Personally I'm really keen on iPad as a platform for interactive fiction. How did you discover and develop the touch-based pinch, pull, and opening mechanics the player uses to explore the story?

We’re keen too. PRY’s interfaces were very much guided by the project’s story and vice-versa. We discuss our narrative inspiration in the question below. We wanted to make something that could only exist on, and made use of, the constraints and advantages of touchscreen readers. The reading gestures should be integral to the story and not just skeuomorphic remnants from print such as the page turn. Additionally, the pinch gesture has become synonymous with multi-touch interfaces and is an important part of the iPad’s vocabulary.

Where did you derive the inspiration for the narrative itself?

We began PRY while working on a project (with experimental theater troupe Piehole) inspired by updating the biblical story of Judith and Holofernes. In the original story, Judith beheads Holofernes. Throughout PRY, our character both loses his vision and becomes progressively detached from the world. We began to brainstorm interfaces that played with vision, internal and external worlds. Because the character is introspective about his past, we worked on crafting interfaces that evoke the fragmentary and elusive nature of thought and memory.

Much of the original story and characters evolved; however, the setting and some interfaces remain. A vision-based interface created the idea of being inside the mindscape and witnessing the story through POV. Ultimately, we drew on our own histories and experiences. We use the specific characters and setting to tell a more universal, human story about how we reconcile and twist the memories of what we’ve done into a present-day identity.

In PRY, at the player's discretion, the character alternates between looking within for answers, and looking around. How did you decide on this as the core mechanic?

The story itself is an intimate character study. In addition to thinking about how a character becomes more “detached” from the world, our character is also looking for answers within himself to understand past events and reconstruct memories. Samantha, especially, has worked with branching narrative structures before and wanted to try and create something that wasn’t quite branching (dialogue paths and different endings), but still feels very exploratory and responsive.

Instead PRY is a highly authored experience that retains its feelings of exploration by nesting different versions and conflicting memories of the same events and tasking the player with piecing it all together. The player’s control is that of a ghost or privileged guest inside the protagonist’s mind. In some ways, PRY’s narrative structure is reminiscent of something like Gone Home, but the player rifles through fleeting thoughts rather than crumpled notes.

What are your thoughts on the possibilities for interactive fiction design on current platforms?

It’s a great time for interactive fiction. Increasingly, we consume fiction on mobile devices that have a huge array of sensors and processing power that can be used to create really unique and interesting experiences. We’re excited by the idea that interfaces and gestures can be just as much a part of a story as the plot itself. More and more, it seems like there's a growing range of experimental narrative games.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any you've particularly enjoyed?

We’ve been in full-swing production (Part 2 will be launched in April), but we still find time to play games. We are very excited about playing all the IGF games and got to spend some time with a few of the games at IndieCade. We’re big fans of Framed, and are also looking forward to experiencing Ice-Bound further. We were working through PRY when Device 6 came out. It was such a nice breath of fresh air for us and made us really optimistic about the future of interactive fiction. From past years, we found inspiration in games such as The Stanley Parable, Dys4ia, and Gone Home.

You May Also Like