Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus provides inspirational purpose to the themes of death and gore in video game storytelling through tragedy driven plotlines, deeper character development, and elements of spectacle for today's desensitized audience.

Shakespeare has often turned to the genre of tragedy to captivate audiences in stories of conflict, deceit, and revenge. While the concept of love is often at the core of his plays, it is the cost of love that often leads to the tragic events of the characters, the kingdoms, and legacies that may fall in its wake. Violence and death are main ingredients of tragedy and are often justified or glorified by Shakespeare to build engaging narratives.

Shakespeare has often turned to the genre of tragedy to captivate audiences in stories of conflict, deceit, and revenge. While the concept of love is often at the core of his plays, it is the cost of love that often leads to the tragic events of the characters, the kingdoms, and legacies that may fall in its wake. Violence and death are main ingredients of tragedy and are often justified or glorified by Shakespeare to build engaging narratives.

While modern society holds the works of Shakespeare in the high regard of classic and influential literature, it is interesting that controversy often surrounds the violence and gore in today’s storytelling experiences of video games. Looking at Shakespeare’s goriest play, the role of violence and death will be examined as artistic storytelling platforms in which to compare and contrast with modern game narratives to reveal the importance of these controversial themes as dramatic elements of quality storytelling. Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Titus Andronicus provides inspirational purpose to the themes of death and gore in the modern storytelling genre of video games through the investment of tragedy driven plotlines, fueling deeper character development, and creating elements of spectacle for today’s desensitized audience.

A good plot can be driven by conflict and a character’s need to overcome challenges. Revenge is usually a good catalyst to set protagonists on a journey to right the wrongs that have been done unto them or those closest to them since “the mode of violence that has attracted most critical attention is revenge, which, in transferring a desire for retribution from a murdered character to survivors, raises questions of duty, justice, and loyalty,” (Foakes, 16).

Whether the protagonist’s role is one of a hero or anti-hero, the concepts of revenge and vengeance are often presented as a justifiable reason to seek retribution, and usually match or exceed the original sin. Thus, a violent act often promotes a violent response. The Tragedy of Titus Andronicus consistently reaffirms its theme of revenge, beginning with the vengeance launched against Titus for sacrificing Tamora’s son, a death of dismemberment which, in itself, is a form of retribution for the loss of his own sons during previous battles in the play’s backstory. It is Demetrius’ words that first signal this intent stating “madam, stand resolved; but hope withal the selfsame gods that armed the Queen of Troy with opportunity of sharp revenge upon the Thracian tyrant in his tent, may favour Tamora, the Queen of Goths,” (I, I, 138-142). Upon the capture and death of Titus’ sons as a result of Tamora’s vengeful schemes, the response by Titus is first voiced by the character of Marcus, saying “we will prosecute, by good advice, mortal revenge upon these traitorous Goths, and see their blood, or die with this reproach,” (IV, I, 91-93). Many deaths and violent acts occur based on plotlines of revenge and disparity and we can see in these examples that it is a reoccurring theme.

Storytelling in video games is an evolving art form and growing in expectation. While there are many games that that feature weak stories, or no stories, violence can end up having no narrative purpose at all…senseless. Yet, as narratives grow in importance, many games are adopting plot driven themes of revenge. In keeping with Roman mythology, God of War features the anti-hero, Kratos, a violent warrior, who upon meeting a coming defeat, praises to Ares, the God of War for redemption. It is an act that turns Kratos into Ares’ weapon of carnage. In a fit of uncontrollable rage, Kratos slays his innocent wife and child. From that point on, Kratos is set upon a journey of dismembering his adversaries to exact his revenge upon Ares. Hacking and slashing of epic proportions.

Storytelling in video games is an evolving art form and growing in expectation. While there are many games that that feature weak stories, or no stories, violence can end up having no narrative purpose at all…senseless. Yet, as narratives grow in importance, many games are adopting plot driven themes of revenge. In keeping with Roman mythology, God of War features the anti-hero, Kratos, a violent warrior, who upon meeting a coming defeat, praises to Ares, the God of War for redemption. It is an act that turns Kratos into Ares’ weapon of carnage. In a fit of uncontrollable rage, Kratos slays his innocent wife and child. From that point on, Kratos is set upon a journey of dismembering his adversaries to exact his revenge upon Ares. Hacking and slashing of epic proportions.

The Last of Us (spoiler - first level ending) is a game that features a character, a father who in the opening chapter of the game’s story, witnesses the death of his young daughter as she takes her last breath in his sorrowful arms, a victim of an accidental shooting. The experience shapes how the character reacts and perceives the events that he faces throughout the rest of the story, haunted by the past. It isn’t revenge that fuels the character, it is the pain of loss that alters his perception of the world and future characters that fill out the story’s cast. Rather than the motivation of vengeance, his actions become more preventative than offensive and the role of protector is formed through desperation. Either way, it is a reactionary evolution based on the influence of personal loss, the death of his child.

Character development is well-served by acts of violence and death in a story, and The Tragedy of Titus Andronicus is no exception. While revenge can provide character motivation, as experienced by Tamora and Titus, it is interesting to see the personified character of Revenge, imitated by Tamora, in an attempt to exploit what appears to be Titus’s madness for the purposes of manipulating him to convince his son to stop his Goth army’s attack upon Rome. Yet, it is Titus’s tragic journey of lost lives and violent acts that stirs and changes his character over the course of the play. While there are many scenes to choose from, the concept of dismemberment plays a central role in the play. A defining moment is when Titus seeks to have his two son’s freed and Aaron the Moor announces to him that his amputated hand will secure their release. As his companions evaluate who’s hand it shall be, Titus states, “My hand hath been but idle; let it serve to ransom my two nephews from their death, then have I kept it to a worthy end,” (III, I, 171-173). Then Aaron chops off his hand and the play’s viewing audience begins to witness the extraordinary lengths Titus will go to for his family through self-sacrifice, and perhaps flirt with insanity. As the story unfolds, Titus’s madness is unveiled as a ruse and the revenge-fueled monster is released when a scene of spectacular violence unfolds towards the end of the play. Before exploring this role of spectacle, the specific act of dismemberment, is a familiar scene in some popular games.

Character development is well-served by acts of violence and death in a story, and The Tragedy of Titus Andronicus is no exception. While revenge can provide character motivation, as experienced by Tamora and Titus, it is interesting to see the personified character of Revenge, imitated by Tamora, in an attempt to exploit what appears to be Titus’s madness for the purposes of manipulating him to convince his son to stop his Goth army’s attack upon Rome. Yet, it is Titus’s tragic journey of lost lives and violent acts that stirs and changes his character over the course of the play. While there are many scenes to choose from, the concept of dismemberment plays a central role in the play. A defining moment is when Titus seeks to have his two son’s freed and Aaron the Moor announces to him that his amputated hand will secure their release. As his companions evaluate who’s hand it shall be, Titus states, “My hand hath been but idle; let it serve to ransom my two nephews from their death, then have I kept it to a worthy end,” (III, I, 171-173). Then Aaron chops off his hand and the play’s viewing audience begins to witness the extraordinary lengths Titus will go to for his family through self-sacrifice, and perhaps flirt with insanity. As the story unfolds, Titus’s madness is unveiled as a ruse and the revenge-fueled monster is released when a scene of spectacular violence unfolds towards the end of the play. Before exploring this role of spectacle, the specific act of dismemberment, is a familiar scene in some popular games.

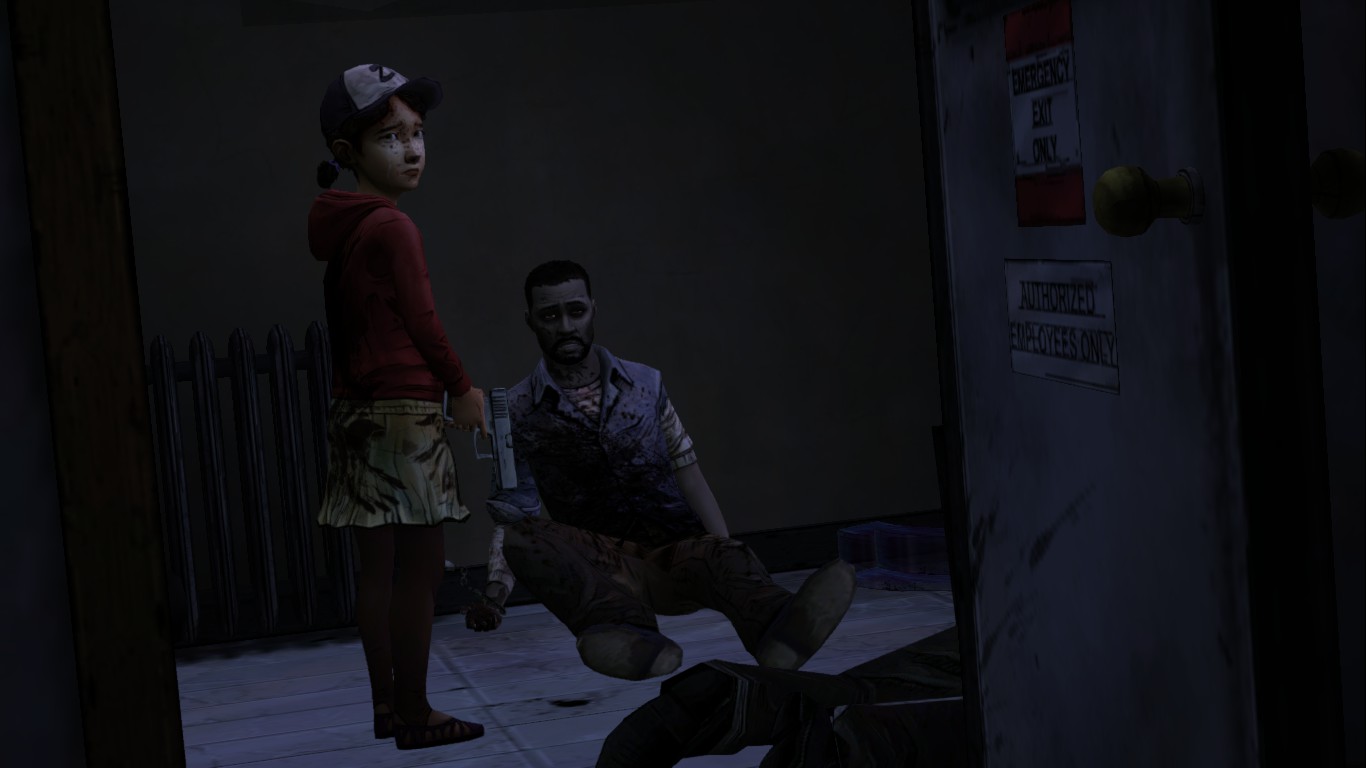

The Walking Dead, (spoiler - Ep 5, plot element), a popular franchise in various forms of media, is very successful in the genre of video games as well, and carries its own original narratives. The protagonist character, Lee Everett, is a good man in a zombie apocalypse. In a world ripe with death and dismemberment, he takes a young girl under his wing and protects her as they embark on a journey of survival. Like the common zombie consequence, Lee eventually ends up bitten in the hand, an event that could cause him to eventually join the roaming corpses as a zombie. In a dramatic moment of gore (and player decisions), Lee’s hand is cut off in an attempt to delay the inevitable, only to ensure the continuance of protection for the young girl, for as long as he can. While gory and disturbing, the scene solidifies and grows the determination of Lee’s character, yet also leads to the strengthening of the young girl as she prepares to survive the hostility of a tainted life. This scene is not your common hack and slash, it’s emotional, and its purpose feels meaningful for the characters and the player.

Similarly, the game Heavy Rain (mild spoiler - plot element) is not so much about revenge, but of desperation, much like Titus longed to have his son’s freed and willingness to suffer unimaginable pain in the process. In this game, the protagonist has had his last surviving son abducted by a serial murderer known as the Origami Killer. The villain orchestrates trials the player character must endure, in hopes to save his precious son. Among the violent acts he must face, out of the love for his son, one task resorts to self-mutilation. The character sits at a table which displays multiple tools such as wire cutters, saws, and other intimidating artifacts. A tool must be chosen which indicates which form of self-mutilation the player will face, including amputation.  While horrific, the scene is certainly a story builder and changes the character as the goal is beyond the self, and rather lies with saving the life of another, a son, just like the sacrifice of Titus’s hand. This is a deep storytelling experience for the player since there is a life in the balance, and an unthinkable choice to make. Offering the player choice in the matter escalates the immersion and, ultimately, the commitment to the brave the torturous scene. It leaves an impact; it’s not a cartoon.

While horrific, the scene is certainly a story builder and changes the character as the goal is beyond the self, and rather lies with saving the life of another, a son, just like the sacrifice of Titus’s hand. This is a deep storytelling experience for the player since there is a life in the balance, and an unthinkable choice to make. Offering the player choice in the matter escalates the immersion and, ultimately, the commitment to the brave the torturous scene. It leaves an impact; it’s not a cartoon.

Spectacle, according the Aristotle, is one of main components of narrative, and The Tragedy of Titus Andronicus sets the bar among Shakespeare’s works. Two main scenes capture the role of spectacle at its grandest in this play. The tragedy of Lavinia, Titus’ daughter, provides a gruesome, haunting scene where, after being raped by two degenerates, Demetrius and Chiron, Shakespeare “pushes the boundaries of such spectacle further. Not only are Lavinia’s hands cut off, and her tongue cut out, but Marcus draws attention to the blood that pours from her,” (Foakes, 55). This is a scene that captures the horror of tortured innocence and a grotesque display of mutilation. The film adaptation presents the character with branches protruding from her bloody stumps, mocking where hands once were, and she stands in the middle of a field like a sacrificial scarecrow of suffering. In attempting to speak, blood spews from her mouth like vomitus death. Upon identifying her attackers, the event becomes the catalyst that fuels Titus’s rage and leaves such an impact on an audience, that empathy can almost be felt for the atrocities yet to be committed by Titus in retaliation.

Another impactful spectacle is the famous dinner banquet at the end of the play, and the events leading up to the brutal scene. Titus captures his daughter’s attackers, kills them, and bakes their bodies into pies. In an act of deceived cannibalism, Tamora eats the pies containing both her son’s meaty remains, a scene that is as uncomfortable for the viewers as it is the characters of the story, when Titus gleefully reveals the human ingredients. Titus then draws a blade and kills his daughter, Lavinia, in shame of the family name, and follows by killing Tamora. The deaths continue with medieval intent, including Titus, and few at the banquet remain alive. The scene has been such a disturbing spectacle in live performances that a “spokesman for the Globe confirmed five members of the audience fainted in a particularly gory five-minute scene,” (Furness). The scene is certainly gory, yet provides a solid climactic purpose for all the events that produced such a spectacle. Some video games provide similar instances as these, but the gratuitous nature of violence in games tends to stir controversy.

Many games take the spectacle violence too far, at least for some people, and make it a constant act rather than impactful storytelling moments. For example, Dead Rising 3 requires players to constantly hack and slash enemy characters, and actually tallies the count of deaths and dismemberments achieved by the player, into the thousands. While Shakespeare may have explored violence as entertainment, we certainly don’t see it at this level. The Witcher 3 and other similar games such as the Fallout series, Ryse: Son of Rome, and Sniper Elite 3, have features that actually slow down the moments of action where death and dismemberment take place to glorify each gruesome and bloody death which involve decapitations and dismemberments. Games such as Dead Space and The Evil Within, also include slow motion, cinematic, horrible player character death sequences that showcase the macabre of player error. These are gratuitous violent scenes that can be argued in support of those concerned about the level of violence in games today, especially considering the interactive elements of players controlling the action. It does provide the element of spectacle none the less and some thoroughly enjoy the embellished, fantasy gore. However, there are games that explore the spectacles of specific intense scenes and imagery to further the depth and impact of story.

The Bioshock series, as well as The Evil Within, are two very different games that use violently posed scenes of death and dismemberment to fuel a sense of spectacle when exploring the environments of the game world. Often staged with lighting, brief messages scrawled on the walls, and artistically positioned corpses, these scenes are not ones of action, but of environmental storytelling. The scenes mimic the tortuous events of Lavinia’s tragic mutilation and are often used to leave an emotive impact on players to heighten a sense of discomfort and fear. Some can be quite disturbing and unusual and can have a direct impact on how players perceive their surroundings, or how they proceed.

While games usually avoid grand death scenes of multiple cast members for the sake of potential sequels, and the amount of expensive development necessary to create such characters, they still use character deaths as a form of spectacle. Where the Game of Thrones books and television series might have been influenced by Shakespeare’s banquet scene, games often span out the high level character deaths to promote the rollercoaster of emotion that spans many hours of gameplay. Big deaths can have a dramatic impact, especially considering the investment and participation players have had in how the game’s story unfolds. Revisiting The Walking Dead game (spoiler - ending), the final act of season one sees the protagonist character facing the unfortunate horror of turning into a zombie. In successfully protecting the young girl, Clementine, for as long as he could, an emotional goodbye is delivered. In a final moment of spectacle, Lee hands Clementine the gun and asks to be relieved. The player then plays anew, as Clementine, and emotionally, compassionately, makes a difficult choice. One option takes the life of the fallen protector. It is a very impactful and sad scene for players to see such a hero that they have guided through the story fall, but the story is better for it. It’s tremendously better because a player can feel the lump in the throat, the heaviness of the chest…it means something and the player feels it.

There is no denying that many games exploit the role of violence and death to attract audiences to the product. Considering the level of violence in today’s television shows, movies, cartoons, comic books, and even in the news, society has become desensitized to the role death plays in works of fiction. Yet, when looking at how Shakespeare utilized violence and death as dramatic methods of storytelling to build upon plot, develop character motivations, and provide significant moments of spectacle, modern games can continue to learn from his narrative approach. As game storytelling improves, violence in games may begin to be recognized as art, rather than considered elements of controversy and concern.

Written by Gregory Wells

Works Cited

Bajovic, Mirjana. “Violent Video Game Playing, Moral Reasoning, and Attitudes Towards Violence in Adolescents: Is There a Connection?” Faculty of Education, Brock University. 2011. Web. 20 October. 2015.

Foakes, R. A. “Shakespeare and Violence. New York.” Cambridge University Press, 2003. Web. 20 October. 2015.

Furness, Hannah. “Globe audience faints at ‘grotesquely violent’ Titus Andronicus.” The Telegraph. 2014. Web. 27 Sept., 2014.

Gregg, Steven. “Titus Andronicus and the Nightmares of Violence and Consumption.” University College London. 2010. Web. 8 Oct., 2015.

Griffiths, Mark. “Violent Video Games and Aggression: A Review of the Literature.” Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol 4, No 2. USA: Elsevier Science Ltd, 1998. Print.

Marquardt, Anne-Kathrin. “The Spectacle of Violence in Julie Taymor’s Titus: Ethics and Aesthetics.” Societe Francaise Shakespeare. 2010. Web. 8 Oct., 2015.

Parkin, Simon. “Beyond the Shoot-em-up: How Gaming Got Killer Stories.” The Guardian. 2014. Web. 7 Oct.., 2015.

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of Titus Andronicus. Amazon Digital Services Inc. (n.d).

SparkNotes Editors. “SparkNote on Titus Andronicus.” SparkNotes.com. SparkNotes LLC. n.d.. Web. 23 Oct. 2015.

Tria, Jaya. “Shakespeare in Video Games.” Transmedial Shakespeare. Ateneo de Manila University. 2011. Web. 22 Oct. 2015.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like