Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Multifaceted theories of motivation propose a fixed number of basic desires that motivate human behavior. Is your game tapping into them?

From Motivate. Play.

7 Habits of Highly Effective People. The 8 Essential Steps to Conflict Resolution. I’ll be the first to agree that including an arbitrary number in a headline makes an article sound like something that you’d find in the bargain bin of your local bookstore, but in this case there’s a rationale.

In a series of studies from 1995 to 1998 that investigated fundamental human drives/motives for action (status, hunger, sex, etc.), Dr. Steven Reiss and colleagues started with a list of “every motive they could imagine,” including hundreds of possibilities drawn from psychological studies, psychiatric classification manuals, and other sources.

They whittled this down to a mere 384, and distributed a survey designed to measure the importance that survey-takers assigned to each motive to over 2,500 people.

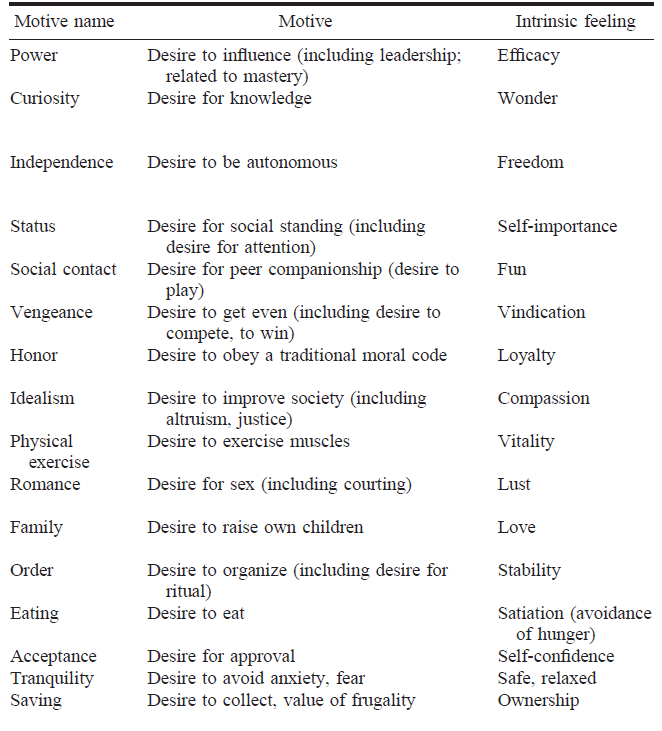

Plugging the results into a factor analysis to find out how many distinct underlying dimensions were necessary to account for the majority of variance yielded 15 distinct clusters of motives that people rated as of particularly high importance. (They added one more in 1998). In no particular order, they are:

Reiss' 15 Fundamental Motives

Based on Multifaceted Nature of Intrinsic Motivation: The Theory of 16 Basic Desires, Table 1.

This is at odds with the reigning approach of dividing motivations up into extrinsic vs. intrinsic, and is much messier from a theoretical perspective. But as the psychologists who conducted the studies argue, there’s no reason to expect that an adequate theory of something as complex as human motivation should be anything but messy.

We have over 50 distinct cortical regions, over 100 different neurotransmitters, and thousands of proteins. Why not at least a handful of innate motivational categories?

Certainly, the theory has its flaws. There is ample evidence that people don’t have a good grasp of what really motivates them (which puts limits on what we can learn from surveys), and the theory doesn’t do justice to fact that our reactions to “things we want” vs. “things we want to avoid” are subserved by different neural systems. But it certainly provides an interesting perspective.

Many designers were astounded at the popularity of Farmville, whose key mechanics flew in the face of received game design wisdom, and Zynga’s continuing demise has been heralded by some as proof that the intrinsic motivation provided by a good game ultimately trumps the extrinsic motivation of praise and badges. Maybe so.

But it’s also possible that the motives that Farmville’s core mechanics tap into—accumulating items (Reiss’ “saving” motive) and the desire to give a Green Whatsit to someone who gave you a Blue Doohickey (reciprocal altruism, which falls under Reiss’ “idealism” motive)—are not inherently ‘worse’ than other motives, just hard to sustain in the long term in the absence of other motivating features. Arguably, many good MMOs take ample advantage of both of these motives and many more besides.

My previous post highlighted some of the difficulties of designing intrinsic motivators into a game. Even if the intrinsic/extrinsic distinction is a meaningful and important one to make, the difficulties of navigating this space in a real-world game may make multi-factor theories more useful to game designers in practical terms.

In particular, they can be used as “lenses” in the sense of Jesse Schell in The Art of Game Design, which contains 100 thought-provoking lenses through which one’s game can be viewed and improved. One can imagine developing corresponding lenses for each of Reiss’ fundamental motives (e.g. “The Lens of Independence: Does my game make people feel autonomous? Do players have a sense of control over their actions? Do they feel free to select from meaningful choices?”)—and in fact, Schell’s list already includes several that are relevant to some of the motives above (The Lens of Competition, The Lens of Cooperation, The Lens of Needs, The Lens of Control, The Lens of Community).

(Drawing up lens cards for Reiss’ remaining motives, and designing a game that satisfies the motives of “desire to eat,” “desire for sex,” and “desire to raise own children” is left as an exercise to the reader.)

Although most designers already have a sense of what motivates their audience, focusing one’s attention on the sixteen dimensions that have emerged as particularly important in large-scale studies of human motivation may be a worthy endeavor, if for no other reason than to identify which motives one’s game already addresses best, and to evaluate whether ramping those up even more would improve it further.

In addition to features that conventional wisdom suggests are motivating to players (rewards for skill development, compelling narrative, gradually increasing difficulty, etc.), ’16 Basic Desires’ theory may inspire further ideas for underappreciated features worthy of consideration.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like