Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Originally presented as part of GDC 2013's Level Design in a Day bootcamp, this talk covers the how and the why of Bethesda Game Studios' approach to creating the modular art used in level design.

We recently realized that there are many unspoken understandings we and our colleagues share; expectations and assumptions taken for granted as part of our process. We've struggled to explain ourselves in detail for new artists and designers who had joined our team. This talk was a way for us to explore and articulate this accumulated knowledge. To understand our approach, it’s useful to know where we’re coming from as developers, and where Bethesda Game Studios is coming from as a whole.

Let's begin with a pretty simple observation: our games are big. If you've played or read about Skyrim, Fallout 3 or any of our other open-world games, scope is a big part of them. It’s an integral part of our games and our DNA as a studio. You couldn't boil Skyrim down to a six-hour game and expect to provide the same experience. Scope isn't a random attribute of our games; it’s a major feature.

When you play a Bethesda game (or when you work on one) you know this going in. The games are big! This influences everything we do at the studio. Production methodologies, tech and tools, workflow, pipeline - it’s all informed by a need for efficiency. We need high bang-for-buck on everything we do. Games like Skyrim take a few years to make, even moving as efficiently as possible. With a game that big, missteps aren’t measured in hours or days, but scale to weeks and months.

These core values, along with the circumstances of team size, and our collective experience making games together all adds up to what you’d commonly refer to as studio culture. Even if your team or your game isn’t driven by the same forces as ours, chances are you could take a lesson from us, just as we could probably take a lesson from you.

With that in mind, consider this a case study. The modular approach to level design we’re analyzing here is just one manifestation of the BGS studio culture.

Before getting too far into things, let's me define what a “kit” is. Kits, first and foremost, are systems. A basic pipe kit, like the one from Fallout 3, may only be four simple pieces of art which can be used together. This kit, as most, snaps together using a grid system. The most important attribute of a kit is that it adds up to far more than the sum of its parts. This artist hasn't just given us four pieces, but a system with which we can create infinite configurations of pipes, all on the editor side.

While the pipe kit is a good example of a simple art kit, our primary topic here is architectural kit creation. Examples of architectural kits would include the Nord Crypts in Skyrim, or the Vaults from Fallout 3. This is important to topic for gameplay, because kits are the primary building blocks of level design at Bethesda Game Studios. Kits aren't a new idea. They aren’t unique to Bethesda or to the types of games we make. Consider the board game Carcassone. Unlike Monopoly or Scrabble, the board changes every time you play Carcassone. The tiles are arranged so that roads meet roads, rivers meet rivers, and so on, creating an effectively randomized yet visually cohesive whole. It’s easy to see the grid when looking at a Carcassone table, and how this system of art works together to make a unique play field. The board tiles are themselves an excellent example of an environmental art kit.

Many sprite-based, 2D games make heavy use of similar ideas and techniques to those we’ll be discussing today. Sprite sheet or texture atlas technology lies at the heart of many 2D game systems, so it’s easy to see how those games lend themselves to repeatable tiles of a uniform size. Thanks to this, it’s not necessary to paint the entire world by hand. Designers and artists can use art systems of repeated tiles to draw out the map quickly and with less of memory footprint.

Back in November of 2002, Lee Perry (then of Epic, now BitMonster) authored an article in Game Developer magazine which explored a modular approach to level design and world building, specifically as a way to help cope with the increased fidelity of games at that time. Bethesda has been at this for quite some time - 18 year as of this writing. Terminator: Future Shock and the Elder Scrolls 2: Daggerfall, both games which far pre-date our (Nate and Joel's) tenure at the studio, embraced a modular approach to world-building, which would become the foundation upon which much of our current thinking and technology are built.

So remember - the concepts discussed today are far more than the product of our work together over the past decade. Many influences and ideas have contributed to our current workflow, and there are many lessons yet to be learned.

As mentioned earlier, many developers understand the principles behind modular level design, but we hope to offer insights gained from our extensive exploration of this topic. To do this, we’ll go over the various benefits and drawbacks we've found over the years, with an emphasis on how to get the most out of the workflow.

The first, most self-evident benefit of working with modular art is that it’s reusable. Reusing art helps us mitigate the huge scope of our games. There’s a massive amount of world-building to be done in Skyrim, and not having to specifically create and export every fence post and doorway becomes very important to us. We try to be smart about where we spend our time and attention, reusing art where it makes sense, and investing time where we want something more unique.

Consider this list of features, which together make up the rough measure of Skyrim’s world-building needs:

16 sq. mile Overworld

5 Major Cities

2 Hidden Worldspaces

300+ Dungeons

140+ Points of Interest

37 Towns, Farms & Villages

Now consider that alongside this photograph of the Skyrim development team. There are 90 people in the photograph below. With the exception of a small number of outsourced assets, you’re looking at the entirety of the dev team across all disciplines. We've resisted the temptation to grow into a multi-studio team of hundreds, such as you often find behind games of similar scope to those we make.

Today we're focused on what you’d most typically associate with traditional level design at Bethesda; the dungeons component of that world-building work. Only ten people out of the 90 in that photograph are directly responsible for those dungeons. The rest of the team is focused on the myriad other features, content, systems and support needed to build a game like Skyrim. You can begin to appreciate how small our dev team really is when you consider how much responsibility each person needs to shoulder.

Sooner or later while reading this, you may think that the scope of the game is a restriction that limits our ability in some way, that it’s a burden we wish we could shrug off. The thing is - even if our circumstances were different, and we had infinite time, resources, or talent - I don’t think the way we make games would look all that different We've found a way that works for us.

Consider the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, famous in particular for his work in Paris during the 1920’s. You may not know Mondrian by name, but you’re likely to recognize his work, such as the piece seen below. Mondrian had access to more than four colors of paint, and was certainly capable of more technically complex work. Yet he chose to self-impose restrictions which led him to pioneer a style he may not have otherwise discovered. The influence of that style is still felt today in art and fashion.

Look throughout the history of science, technology, music, anywhere people are creating, and you’ll find examples of restrictions not limiting creativity, but focusing it and leading people toward new discoveries and innovations. I think our workflow is like that. To change it because of a shift in circumstance would be ignoring the belief systems and experience that led us to that conclusion.

Getting back to the topic at hand, we should also acknowledge the most self-evident drawback of using modular art: the fact that resused art can become repetitive. This leads to what we commonly refer to as “art fatigue”. The median play time of Skyrim on Steam has peaked at well over 100 hours, which is a huge compliment . With that kind of time spent, however, players are bound to notice the same rock or farmhouse or tapestry used again and again. And another two dozen times after. Art fatigue sets in where this repetition becomes obvious and erodes the authenticity of the world.

We've found some ways to delay the onset of Art Fatigue. One of the big ones is simply doing away with copy and paste design as much as possible. When I first joined Bethesda, Oblivion was poised for the home stretch of its development cycle. Oblivion was of similar scope to Skyrim, yet built by a team of about half the size. One of the ways the dungeon art team coped with this disparity was to create a number of “warehouse” cells in the editor. These warehouses contained fully lit and cluttered rooms to copy, paste, and then arrange to create "new" dungeons. While efficient, this method left much to be desired, and many players rightfully called Oblivion dungeons out as being “cookie-cutter”.

One thing we noticed was that players were quicker to react negatively to repeated detail elements, as opposed to broad architectural repetition. Consider the following three screenshots, each taken from a separate Oblivion Dungeon.

In each, you’re more likely to pick up on repeated clutter first, then the repeated architecture. This is especially true in actual gameplay from a first-person perspective. To minimize needless repetition, we abolished the use of warehouse cells as they existed in Oblivion. Beginning with Fallout 3, we staffed up a group of level designers and got tool support to make sure we were able to build spaces more quickly, and with the most granular art available, reducing the amount of repetition as much as we possibly could.

You can also fight art fatigue at a more fundamental level. It’s common at the start of a project to strongly associate a particular setting with specific types of inhabitants or gameplay. You may want to only see soldiers in military bases, and zombies in crypts, for example. Resist this. Think of your kits as the architectural identity of the space, and allow other elements to establish the specific identity of any given space in which it’s used. The more you’re able to divorce these things, the more you’ll be able to mix elements up and keep the settings fresh.

This also applies to the kits themselves - try to actively encourage the notion of mix-and-matching your kits. This is sometimes called kit-bashing, kit-jamming, or a kit mashup.

Look the following examples of Dwarven dungeons from Skyrim. The first delivers on the expectation of any Dwemer dungeon in an Elder Scrolls game. There’s a chunkiness of proportion, an emphasis on brass highlights and clockwork elements which are all hallmarks of that style. Skyrim features around ten of these dungeons, however, and they’re all pretty big. If they were all the same, it’d be a dull, one-note experience, and take the thrill out of discovering one.

To try and mix things up, we started playing around with ideas like combining exterior elements. In the second example we've introduced some lightweight unique assets and enemies you’ll only encounter in this particular Dwarven dungeon. This twist on visual and gameplay expectation helps keep the setting fresh and combats art fatigue.

In the third example, the level designer simply tried bashing Dwarven hallways with ice caves. What he achieved was an instant shift in tone and atmosphere. Some artists will be uncomfortable with this idea. The notion of your art being used in unforeseen ways could lead to bad intersections or lighting issues, for example. To work on this kind of game, however, you need to take a couple of steps back and be open to this. Allow for this kind of experimentation and have it in mind when you’re creating the art to begin with. Not every combination will look good or make sense, but you can be part of a conversation about what works, what doesn't - and most importantly, what almost works, but could work great - with a little tweak from you.

Looking again towards the benefits of working modular, one of the big bonuses (especially from a production viewpoint) is that a modular approach helps if your team has a low ratio of artists to designers. Remember the ten people responsible for the dungeon content in Skyrim? Eight of them are the level designers, and only two represent the entirety of our full-time kit art team. They generated seven kits, which the level design team used to create well over 400 cells, or unique loaded interiors, of dungeon content. And those dungeons were built in about two and a half years, from start to finish.

To put this into proportion, the infographic shown here represents the kit art team as yellow, level design as orange, and the blue-gray area as a conservative estimate of the dungeon content created by that collective group.

There are two points to make here. The first and most obvious: this approach allows a small number of artists to support a much larger team of designers, who can in turn generate a lot more content than those two artists otherwise could. The example provided by Skyrim shows just how effective this approach can be, when only two artists were required to provide the core art behind so much content.

The second, less-obvious point is the more important one, however. Think of the other 80 people in that team photograph. Because such a relatively small group was able to handle the dungeon component of the game, it allowed the rest to focus on the myriad other needs of the game, whether it was landscaping the massive world, writing and scripting the many quests, contributing to character art and animation, working in the guts of our game code.

Of course, there’s another reason that Skyrim had only two full-time kit artists; kits are really complicated things to work on. Kits require not only the artistic ability to produce high quality visuals, but also a technical competency in their art tool, a deep understanding of the editor and design workflow, and so on. This unique blend of left and right brain is somewhat at odds with what many art professionals value. I've worked with great artists who make excellent kits but hate working on them - so they don't.

So when you’re trying to identify somebody with the the aptitude and interest to be a great kit artist, you’re basically looking for a unicorn. They're rare.

Another example of the problematic complexity of kits is the process of identifying and fixing bugs with them. Kits aren't like other art assets, for which you might be asked to fix a bad pivot point or texture seam, but are otherwise fire-and-forget. It’s important and necessary that a kit artist can keep the entire system of rules in her head throughout the entire project. Kit pieces are instantiated dozens or even hundreds of times throughout the game. Making an obvious fix to something like a bad pivot point may address a specific bug but create new problems in those hundreds of instances elsewhere that you may not have thought to check.

This does bring us to one of the other benefits or our approach, however, which is the very fact that kit pieces are heavily instantiated. When a change goes into a kit, those changes are instantly viewable across the whole game. As an artist, performing an export is like a fly-by deployment of new art, whether the level designers were waiting with bated breath or don’t really care.

For artists this allows you to see your art in real-world use cases right away. There's no need to construct a test area. Just load up any level making use of your art and check it out. See how it really appears in game instantly.

This deployment process also has minimal impact on the design workflow, which is not free, but something we work very hard towards. We’ll go into more detail later, but consider this. It’s often been the case that early in a project, art is trying to answer a lot of questions about how the game should look, and kits are no exception. This aesthetic process can be unstructured and time-consuming. The trouble is - design is often twiddling their thumbs at this stage, waiting for something to work with. This can result in art rushing through their process too quickly, sometimes making decisions they’ll change later, in ways that can drastically effect level design and force work to be thrown out or heavily revised.

To avoid this, we get our kits to a "functional-but-ugly" state as soon as possible. This is discussed in more detail later, but the high-level idea is that we figure out as much as we can about how kits work first, which allows design to get working while art then can focus on their visual direction without being rushed.

This is one of the contributing factors to another perk we enjoy; Bethesda level designers are quite fast. Because we’re working editor-side with pre-established kits, our level designers are able to iterate on layout extremely quickly. We can sketch with kits right in the editor and push those to the game, playing the results immediately.

In fact, we’d go so far as to suggest that a level designer working with a good kit that she understands is able to iterate faster and truer to final gameplay than any other designer with any other editor or workflow in the industry. This is because she's using the actual, final art and playing it almost as fast as she can work. We don’t have turnaround with art, we don’t have to bake textures or compile geometry, and our markup is fairly minimal.

Ah, but there’s a catch, and it’s one of the major downsides of our approach. When we say that a Bethesda level designer is the fastest, it’s with a big caveat. We specify that she’s working with a good kit. Without that, she’s not just the slowest LD in the industry - she’s a non-starter. We’re totally dependent on the art we work with, which is why the relationship between art and design is so important.

Consider an all-too-common tale from throughout the game industry. There are many variations of this story, but it’s typical that early in a project, designers are figuring out how their levels should play out. They may do this with editor BSP, external art and previs tools, or through paper maps and documentation. Whatever the method, design works on this until they’re happy enough with it to hand it off to art.

Hopefully this process has been well communicated - but in practice it often isn't and the art team ends up in the difficult position of trying to polish something they weren't very involved with. They’ll do an art pass, though, and make the level visually appealing Once they’re at a place they’re happy with, they send it back to design for final markup and scripting. Once design has done that, the level should theoretically be done - right?

Not usually. Level designers often inherit a litany of unforeseen problems when receiving final art for their levels. Cover along a street has been converted into poles too thin to take cover behind. A wall intended as a visual blocker is now a see-though chain-link fence. A bridge now has support beams which occlude sight lines in a major gunfight you had planned.

When work is handed off like this, it's often one of the main fault-lines of communication This story plays out again and again across all manner of games and teams. At best it’s non-optimal. At worst it can be downright toxic and create an atmosphere of hostility between art and design.

We’re no strangers to this. We've had our share of communication problems and finger-pointing, and have sought out ways to avoid the whole mess. This has come largely from seeking more open communication and collaboration.

Some users who download our Creation Kit comment that kits seem impersonal. To these people, our kit-based approach probably seems like anything except collaborative. Kits can seem restrictive when you’re an end-user - and in many ways they are. But this is one area in which the experience of a Bethesda developer differs greatly from that of a Bethesda modder.

Kits don’t simply appear in the editor one day, fully formed from the mind of the artist and complete, with no further pieces coming along. There’s a process we've worked out to establish any kit, and it takes place over a period of time during which a level designer and artist are in full collaboration.

This begins the technical portion, and it's worth establishing a few items. We’ll be referring to abstract units on occasion. If you’re familiar with Unreal units, for example, these are much the same. All you really need to know is that a character is usually about 128 units, or six feet, tall. We are also accustomed to a Z-up environment. If you’re used to Y as the vertical axis, keep this in mind.

There are a number of things you want to establish at a game-wide level before you begin on kits. As mentioned - you want to do this as early as possible. One thing we've found very useful is to determine a uniform dimension for door frames. This has a few benefits. It allows us to transition from kit to kit without unique pieces, as well as allowing easy re-use of doors between kits. More importantly, it gives AI and animation a fixed standard to work from, which can be reinforced throughout the game.

It’s also worth figuring out the most narrow traversable space in the game. We usually stick to a minimum of two character widths. This allows us to avoid pathing problems by ensuring there’s at least enough space for two AI characters to path around each other in any given space. You should also know how steep of an incline your AI can navigate. In our case this has usually been 60 degrees, but you should also know what looks good. The full incline often looks bad for animation, and you may want to embrace 30-45 degree slopes in your kits.

Finally, if you’re making a game with environmentally contextual gameplay, like a cover shooter or platformer, figure out some important gameplay measurements early on. If you’re making a platformer, figure out how far the player can jump. How far can the player fall before dying or taking damage? If a cover shooter, know what height of cover I can shoot out from.

Keeping this kind of information in mind early will allow you to build kits that make the game look and play its best throughout.

With that, we’re ready to get into what happens once we’re ready to actually start building a kit.

When we're ready to begin any kit at Bethesda, a kit artist and a level designer are both assigned to that kit. There are several stages they'll go through in the initial establishment of that kit.

1) The Concept Phase

The first stage of building a kit is what we call the concept phase. This doesn't literally mean "concept art", although that is often involved. Rather, this is the stage at which we're first deciding upon the main ideas that will drive the kit.

The main goal of this phase is to figure out the big picture ideas of the kit and how it fits in with the rest of the game. This usually takes a relatively short period of time because it doesn't involve any actual content creation. Instead, you're mainly answering questions. What is the visual theme of the kit? How is it different from other areas in the game? What kinds of spaces do you want to build with it? How will be it be used? How often will it be used? Some of these answers will be driven by design, others by art - it's important that both voices are being represented from the very beginning.

Much of the visual process at this stage consists of gathering reference, working with concept art when applicable, and making sure we're all on the same page with the art direction for this kit. There are workflow and logistical questions we start asking at this stage as well, however.

Probably the most important question to answer is this: How widely-used will the kit be? This drives almost every decision when it comes to kit creation. For instance, the Cave Kit in Skyrim is used over 200 times, but the Ratway kit is only used twice. Consequently, the scopes of these two kits are very different.

This also influences the number of "Sub-Kits" that each kit has. A sub-kit is what we call each part of the kit that works with the rest of it. Common examples include a "small room" sub-kit, or a "large hallway" sub-kit. The cave kit has seven sub-kits, while the Ratway has only three. The number of pieces in each of these sub-kits also varies between kits. The "small hallway" cave sub-kit has around 50 pieces. The Ratway hall sub-kit has only seven pieces. Knowing the scope of a kit will help you make good decisions about how robust the kit will need to be, and how much time should be spent building it.

2) The Proof Phase

Once we're satisfied that we understand the big ideas driving the kit, we need to prove those ideas out. This is called the "Proof Phase".

The point of this phase is to start to test out the major concepts of the kit, and it's the first point at which we'll begin building actual assets to bring into the editor.

We're still keeping everything fairly high-level and not getting too deeply involved with building the art, however. Proof pieces have almost no mesh detail and usually no textures at all. Instead, we'll be playing with proportions, kit logic, naming conventions, and other basic needs. Because of that, this stage of the process is also relatively quick, often only 1-3 weeks, depending on the scope of the kit, and how many failed iterations of the proof pieces end up being created and disposed of.

Before we can create the first mesh, however, there are several important details you have to know about kit-building.

First, we have to agree upon one of the most important details for any kit - its footprint. The footprint is the foundation of the entire kit. The most common footprints for kits are equilateral, but other proportions can lead to kits with their own distinct feel. These fundamental decisions are very important, as it will influence the visual identity of the final kit. In this image, the green grid represents the footprint of several pieces used to build a simple room from Skyrim's completed cave kit.

It's important to note that although the various sub-kits of one kit do not have to share the same footprint, those footprints should be multiples of each other. Otherwise, even if the kit pieces initially snap together, as a kit loops back around on itself, it will no longer line up. For example, a 512x512x512 room will always tile nicely with a 256x256x256 hallway, but a 384x384x384 room will eventually create gaps and/or overlaps.

It is also very important to have your grid snap sizes as large as possible. Level designers tend to build on a grid snap setting of one-half the size of the footprint. If the default snap size is large, it is very easy to work with a kit. Pieces line up quickly and easily, and large gaps make it obvious to spot where pieces aren't lined up.

Avoid attempting to create a kit which tiles on all axes. Hallways kits tend to tile on only one axis, while rooms typically tile on two. An all-axis tiling kit is able to create spaces which stretch out not only horizontally, but also vertically stack and tile on themselves. This kind of kit allows a great deal of building freedom, but is very complex to build and use. When vertical tiling is desired, it's generally wiser to build a separate sub-kit with a fixed horizontal plane size. (See Skyrim's cave and Nordic "shaft" sub-kits for examples)

It's extremely important to note that the footprint is the full bounds of the piece, and not the traversable space of the piece. It is the imaginary grid that things line up on. Pieces always exist within the footprint. The only time a piece is at the edge of the footprint is when it is actually snapping together with another kit piece. Avoid the temptation to build to the edge of the footprint, or even worse, outside of it.

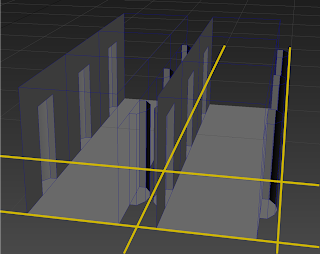

This is most evident in something like a hallway kit. If the walls of the hallway are along the edge of the footprint, there is no room for the walls themselves to exist; they will be co-planar. In the example pieces shown here, a hallway is built using the full extents of the footprint. The alcoves set into each wall extend outside the footprint area, creating an overlap which prohibits hallways running adjacent to each other.

The second diagram shows a revised version of the same piece in which the hallway alcoves are planned and accounted for - they now exist within the footprint, allowing the hallways to run adjacent without incident. Note that level designers could have worked around the overlapping version, but doing so would be placing arbitrary and sometimes-awkward restrictions on layout.

The proof process will help you identify and solve these problems early - save art and design untold hours of work, bugs and frustration that may have come later if we dived too quickly into building visually-complete pieces.

Sidebar: The role of the Level Designer

Let's step away for a moment before continuing to the next phase of kit development. With all this emphasis on art, you may wonder what the role of the level designer is through these phases.

Remember that this isn't something the artist does in isolation and hands off to design later. The process is best when the kit artist and level designer are interfacing on a daily basis. Each is an ambassador of a sort, representing different sets of needs and interests - the shared goal is to preemptively identify these differences and make them topics of conversation. They can otherwise become points of confusion and contention later.

The level designer should be constantly stress testing throughout these stages. The artist should deliver pieces as soon as they are even rudimentarily functional, and the level designer should use them in non-ideal conditions. Only testing a kit as it was intended won’t teach us anything useful. The level designer should anticipate likely (and unlikely) use cases and attempt them, being sure to discuss the ramifications with the kit artist as these expose gaps in kit functionality.

Ultimately, the kit will not be able to support every use case and eventuality. The level designer must choose what the kit does and doesn't support in concert with the kit artist. The idea here is that other designers will eventually discover these limitations first-hand, and the original designer and artist should have answers whenever possible.

Here are a few specific things that the level designer can look for while stress-testing a kit.

One of the big things to do is loop the kit back on itself, usually through various sub-kits. In this example, we’re testing a room and hallway sub-kit. Small hallways tile from the west end of the room and looped around to the south wall. Notice that the southern door fails to line up. It looks like it’s about a half-footprint away from where it should be. A common reaction to this may be to request a half-length hallway. This would fix the specific instance, but it’s what we call a “patch-up” piece, which is really just a band-aid over a deeper problem.

We don’t really care about fixing this specific case; we want to prevent this problem from recurring during normal workflow. So if we look harder, it becomes apparent that we've got a footprint issue with the “2-way”, or hallway corner piece. Notice how it’s longer on one side than the other? That stub is what’s creating the problem. The correct way to fix this problem is to rework that piece so it fits within the intended footprint. It’s good to resist adding patch-up pieces, as they can bloat your kit, add arbitrary and non-obvious usage rules, are usually just symptoms of problems with your core kit.

Something else to try is stacking kits on top of each other. In this example we've placed to hallways right on top of each other. We earlier covered footprint bounds existing within the footprint, and it applies vertically as well as horizontally. This kit uses the entire vertical footprint, creating a co-planar ceiling/floor. This is problematic for a number of reasons: The lack of thickness will be a visual issue if you can ever see it, say from a stairwell or if there’s a hole. It can also cause z-fighting flicker, make optimization and trigger placement very difficult, and generally create a confusing editor view for you.

Instead, predetermine how thick floors should be. This is especially useful with highly architectural kits - something we especially appreciated building the highly architectural, destroyed environments in Fallout 3.

One more common test is to create a pillared room from hall pieces. If you’re a level designer with experience using kits, you probably know were this is going. In this example we've placed a few hallway corners along with several 3-way intersections. In doing so, we've created three "pillars", highlighted in green. This is a classic example of level design using a kit in a way that wasn't intended. These unintended pillars often look bad, but that doesn't mean somebody won’t try it. Somebody always does. This underscores the role of a level designer in the kit development process - the LD should raise these conversations early on and work with the artist to determine what the kit can and cannot support.

The stress-testing process can at times seem combative, it’s important that parties both remember that the end goal is creating a great kit that will produce levels which look great and play great.

3) The Graybox Phase

The next stage is "Graybox". By now, we've figured out the big ideas of the kit and proven that the kit will function. The goal of the graybox phase is to flesh out a kit and to figure out what the most common pieces will be.

Just like the proof phase, the artist is not doing final texture work, keeping piece iteration a relatively quick process. This typically takes 1-4 weeks, depending on the complexity of the kit.

The first graybox should be of the primary sub-kit, or whichever sub-kit we expect to be used most frequently. This helps to figure out the problems early on and enables the kit's level designer to start stress-testing with "real" layout.

Remember to focus on how the kit functions, not how it looks. However; certain visual elements will have an impact and should be roughed in at this stage - usually any visual component that needs to tile across multiple footprints. Each kit has different needs, and you'll have to rely upon your collective vision (established during the concept phase) to figure out which elements these are. If you are making a room kit that has a pipe running down the center, put that in. If you want to build an asymmetrical cave kit, start building obvious asymmetry into the graybox pieces. If you make your graybox too generic, you do not actually solve any problems.

At this point, the level designer and the artist work together to figure out the naming convention. This can be a tedious exercise, but it's important to sort out early.

The key to good naming is balancing brevity with readability.Try to choose naming conventions that will make sense to someone who has never seen it before. If you over-abbreviate, things can quickly become an encoded mess that require a decoder ring to decipher. This can put stumbling blocks in creative process later, as level designers can stumble over looking for the piece they need.

When you have naming conventions that you're happy with, be sure to consistently use them across all kits. This builds a common studio language and makes it easier for level designers to learn and transition to new kits, even across multiple projects.

As an example, let's analyze a piece from Fallout 3, named "UtlBayCorInMidPRTT01L01". If we break the naming convention down, it consists of the following components:

Utl - This indicates that it's a piece of the Utility Kit.

Bay - Indicates it's a member of the Bay sub-kit.

Cor - Cor is our shorthand for "Corner", usually followed by "In" or "Out"

In - This tells us it's an "Inside" corner. "Outside" corners bend the opposite way.

Mid - This is common shorthand for a tiling piece, usually a floor. In this case the bay sub-kit tiles vertically.

PRTT01 - No clue.

L - "Left" We often use L/R at the end of a name to indicate mirrored versions of a piece.

01 - Indicates that this may have visual variants. Discussed in detail later.

Most of the name is easily decoded and consistent with other kits. The "PRTT01" component is indecipherable, however. It was intended to help indicate what the piece will tile with above, below, and on each side - but because it was so difficult to internalize, the kit was underutilized. Which is a real shame, because this kit had a great deal of potential that wasn't tapped for the core game, making some of the effort put into it a waste.

The extreme case of UtlBayCorInMidPRTT01L01 is a useful cautionary tale, but some naming conventions won't fulfill the obvious-to-an-outsider rule. For example, we call a straight hallway piece a "1Way", and a hallway turn/corner is usually called a "2way". More obvious are "3way" and "4way" junctions. We chose this convention because it groups these functionally-similar pieces together in the list, making them easy to get to. Once you understand this name, you'll understand it across all hallway sub-kits because we use it consistently. This is just one case where a slightly obtuse naming convention is justified by the iteration speed benefits and offset by consistent usage.

As briefly mentioned above, It's wise to add 01 as a suffix to any piece which will feature visual variants but otherwise fill an identical role and occupy the same footprint. Even if you are only starting with one of each piece in the beginning, the 01/02/03 suffix format will become useful later, because those pieces will sort together in the list and be easy to find and swap for.

At this point, pivot placement should also be decided upon. Generally, the pivots of our kit pieces are at the ground plane of the kit and in the center. Exceptions do exist however. For instance a pipe kit might have a pivot at the edge of the pipe so that it can hinge like an arm, which makes it easier to line up. A platform kit might have its pivot at the base of the platform instead of the "ground plane" so that it can snap to other areas easier. Changing pivots later can be a huge problem, requiring manual updates to hundreds of instances, especially if the pivot has changed before.

4) The Build-Out Phase

Next up is the "Build-Out" phase. This is when the kit starts to become real art, and can be introduced to the team at large.

With the core pieces proven out and functionally capable of laying out basic levels, the artist can begin developing those pieces visually and adding less-critical pieces and variants in response to usage cases as they present themselves.

This is also a good time for the level designer who has been working on the kit so far to introduce the kit to the rest of the level design team, and give an overview of the thinking behind the kit, its current status and future plans. This is the first stage at which it's a good idea to have other level designers start using the kit for their own layouts, which will generate a lot of useful feedback.

This stage can take much longer because actual textures and geometry are being made. This can take a few months, especially if there are a lot of sub-kits. If the graybox phase was successful, however, level design shouldn't be held up very much: the art can be swapped out seamlessly once the final art exists. This isn't always the case though, so be aware that unforeseen problems can undermine layout being done during build-out.

Even though this article won't go into this in much depth, one very important thing to note is to build out one visually-complete piece before beginning the variants. If adjustments must be made based on art direction feedback, it is much easier to adjust one piece (or a small number of pieces) instead of an entire kit. This can be a massive time savings. Kits will get a lot of polish over time - you're primarily trying to anticipate and avoid changes which will impact functional factors such as footprint, snap rules and pivot point.

Something to watch out for is the temptation to start working on "Hero Pieces". This is a piece that has a lot of fancy unique art, such as a hallway piece with an embedded statue, or a one-off setpiece for a specific event. Even though these pieces seem important, can look really nice and impress everyone on the team, they are ultimately not what is important early on. The hero piece is only used a few times, your normal piece is used hundreds if not thousands of times. Focus on what is actually important; the standard pieces. The hero piece can always come later, and will only be a bottleneck for the handful of specific instances in which they are needed.

Something we've only discovered on our current, unannounced work are what we call "Helper Markers". This is editor-only markup that can help convey meaningful information about the kit. Some examples of this are markers to show how a kit should snap together, where the doorways are or markers for the ceiling so that you don't have to flip the camera upside down to select those pieces. It's good to think about these markers as the level design team starts using the kit, as they can help make usage more intuitive and straightforward.

5) The Polish Phase

Finally we are ready for the polish phase, which is really an ongoing process and that exists (to some extent) throughout the rest of the project. Over the coming months, the kit artist can respond to real usage cases, fix bugs, and additional functionality. Additional art polish will go in as needed, and due to the way that kit art is deployed, this should be a seamless process.

It is important for the level designer and the artist to talk critically about all the requests that come up throughout the process. It is very easy for an artist to say "yes" to every request that comes up. This can quickly lead to a kit that is bloated and unmanageable. Remember the reasons decisions were made while establishing the kit, and make sure that each additional piece is worth it. When adding pieces for a specific use case, see if there is a reasonable alternative, if something else exists already, if the use case is actually worth expanding the kit. The answer won't always be "no", but it can't always be "yes", either. Choose your battles.

During the initial process the artist usually worked with one level designer on a limited set of areas. Throughout the course of the game lots of different level designers will make lots of different levels. No matter how thorough the initial phases were, this always brings up unexpected issues. Assume that this will be the case and plan for additional kit polish time for course-corrections down the road.

At this point you know how to make a rules-based kit on the grid which works as a system. Things snap together, there are corner pieces, straight pieces, doorways, rooms, etc.

The problem with this kind of kit is that it will always feel like a kit. Things are always at 90 degree angles, the player will sense the system and art fatigue can set in. Modular levels often feel like modular levels.

Starting with Fallout 3 we started to push kits beyond this to see how we could make a kit not feel like a kit. We had spent our careers thus far learning the rules; now we needed to break them.

When you start to bend the rules, always keep in mind the reason they were rules in the first place. These ideas exist for a reason, and it can be hard to appreciate why until you've made certain mistakes firsthand.

If you find a way to bend kit logic, you shouldn't necessarily apply that to all kits you make in the future. It is best if you embrace one particular logic quirk for each kit, otherwise things will quickly spiral out of control. It is also extremely important to remember the cost of bending the rules. Art has to spend more time making more pieces and the art is a lot more complicated. The level design process is also usually more complicated and its easier to make mistakes. Make sure these trade-offs are worth it on a case-by-case basis.

One of the key technologies that let us start building more complicated kits was something called "Snap to Reference". With snap to reference the editor can treat any object as the origin for things to snap for. This way, things don't have to be aligned to rigid 90 degree angles. You can rotate a piece and then use that as the new grid, so new pieces will snap together with this rotated piece. This obviously creates gaps between pieces rotated at different angles, but we bridge those gaps in a lot of ways.

One of the new kit types introduced in Skyrim was the "Pivot and Flange" system used for the Ratway. This is a hallway kit that acts almost like a pipe kit. All of the hallway pieces can be rotated at unique angles, allowing for a much more organic flow. Because these hallway pieces are all rotated at arbitrary angles, there is a gap created between each hallway piece.

We covered up this gap using an archway that follows the full curvature of the walls, ceiling and floor. There are a few issues with that you should be aware of. For starters, the level design process is more linear. Instead of knowing exactly how many pieces would be between a set of rooms, since things are rotated at strange angles, all of the numbers/angles are thrown off, which can make it harder to make adjustments.

It's also easy to create non-obvious errors. Because these archways can't snap to both halls, level designers may accidentally fail to align the gap-covering archway exactly right, which can lead to tiny holes that you might only see at just the right angle. (This underscores the importance of playing your work frequently, rather than staying editor-side for too long) It is also a bad system for highly specific architecture. Since it is inherently organic and relies on jamming things together, the visuals break down if you want clean, specific intersections. If you want organic naturally curving hallways however, this system is fantastic and does not require many kit pieces. Because the Ratway is supposed to feel like an ancient, decaying subterranean tunnel system, it's perfect.

We also found ourselves experimenting with our own rules when it came time to build the caves of Skyrim. Caves have always been problematic for modular building, as modular kits are highly rules-based and orthogonal but caves are highly freeform and organic. Another system that we started using in Skyrim is the Shell-Based Building system.

This is a system in which we build all of the standard kit pieces in the traditional way, but then layer in freely placed walls, pillars and balconies to break up the play space in an organic way. The diagram below shows a simple example where shell pieces are used to establish a room, and free walls and pillars are used to quickly create a more organic shape than the corner allowed by the strictly grid-snapped shell.

This allows level designers to build seamless levels with the exact shapes and flow that they want. Visually, it is very easy for things to never look the same. The amount of art that need is surprisingly minimal, due to the random, chaotic way the art can be combined. Some artists might worry about things like specific intersections not looking great. Try using an art-review process to monitor specific usage and provide constructive feedback when things aren't working. Good lighting and rendering features like ambient occlusion also work out very well and go a long way to hide any awkward intersections. The flexibility you can get from doing a level this way is astronomical. (Plus, no one really notices those little intersections.)

Delving further into our history, Directionally restricted kits are a technique we began in Fallout 3. Traditional kits can be rotated in any direction and still snap together. Directional kits do not allow this, as they require certain pieces be used in relationship to each other. This allows art to do things like asymmetrical halls, specific width rooms (such as a room spanned by a large arch) or room kits that have unique pieces for all of the cardinal directions.

This is a lot more work for both art and design, but it is extremely useful for organic kits, as it removes the need for surfaces and textures to tile in every direction. This can be a lot of extra work, and it changes some of the core logic of a kit. While extremely useful for creating natural kits, directional restrictions usually aren't worth the extra effort for something highly architectural. It can make the kit easier to understand if you start thinking of each unique surface differently, such as the A/B sides of the hallway pictured here.

One thing to watch out for when doing this is the need for what we call a "De-Twist" piece in the hallway kits. When an asymmetrical hallway flows in just one direction, it tiles just fine. Sometimes, however, another hallway will meet up that happens to be flipped the other way. A de-twist piece bridges this gap over the course of a single piece by flipping which side meets up with the other. Hence the "de-twist". The following diagram shows an example of an asymmetrical hallway looping back on itself, where it then requires a de-twist.

Another simple kit concept that can add a lot of flexibility is a "platform" kit. Platform kits are any that sit on top of other surfaces, and allow level design to cut up the horizontal planes of play. They can be very large or small, and both examples can be seen in Skyrim. These empower level designers to create interesting playspaces without needing to add a great deal of complex vertical logic to the kits. The number of pieces needed to create a platform kit is minimal, and they tend to work with almost any other sub-kit with the same visuall theme. These platform kits were even used independently in the exterior as points of interest.

Platform kits are a specific example of what we've started to call "Glue" kits. Beginning with our current project, we are now creating a number of small-scope kits which exist primarily to create transitions between multiple kinds of kits and sub-kits. Glue kits are essentially made with kit-bashing in mind, and could be just about anything from platforms to tunnels to ledges. They are so far giving us a good deal of mileage, and show how discoveries and innovations made along the way can begin to influence your formal workflow. Which is good, because an evolving workflow is proof that you're still learning.

There’s an awful lot more that we could cover if we were to get into the deeper details of kit-building, and you’re encouraged to reach out to us with any questions you may have. For now, however, let's wrap up.

When you get down to it, I do not believe our team could have built Skyrim except through our decision to explore and embrace workflows like the ones discussed here. We’re driven by a desire to explore our worlds via their creation, always aware that the time we spend polishing every edge off one idea takes away from what we could be doing with another, and the thing after that. We've said before that the worlds of our games are their own main characters. Those worlds come to life before our very eyes during development.

Don’t mistake these workflows for a compromise into which we have been forced. Rather, these are choices we have made in order to make the scope of our games possible while maintaining a working culture which keeps us happy and harmonious.

Because while I don’t believe our team could have built Skyrim any other way, I also believe that no other team could have made Skyrim. Other teams could have made a game like Skyrim, and perhaps have spent more time or money, or worked with more people, or embraced different ideologies. But any of those games would have been a different one that what we created, and we're proud of the games we've made.

At the end of the day, the games you create - the art you put out into the world - is an expression of yourself. If you’re working as part of a team, however, that art isn't just an expression of your own self, or even many individual selves. It’s an outward expression of your relationships, and who you are as a group of people. And these relationships are perhaps the most rewarding thing you’ll develop in your lifetimes. It's worth finding techniques that help grow those relationships and in turn improve the games you can make together.

Joel Burgess is a senior designer at Bethesda Game Studios, and Nathan Purkeypile is a senior environment artist. Their shared gameography includes Skyrim, Fallout 3, Aeon Flux, Bloodrayne 2, and an unannounced project currently in development. Nate and Joel were also co-leads on the Point Lookout DLC for Fallout 3. They can be reached on twitter via @JoelBurgess and @NPurkeypile, respectively.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like