Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

We made an educational game that the general public seems to like. Here's what we did.

This post is also available on my site, lockandkeychain.net.

A while back, my friend Connor Fallon came to me with an idea: a game that uses Ace Attorney style mechanics to teach players philosophy. It sounded ridiculous, but something about the idea just felt right. That idea eventually became Socrates Jones: Pro Philosopher, a game we released on Kongregate last month.

Our promotional poster

Of course we hoped the game would be successful, but we knew better than to expect miracles. After all, Socrates Jones is pretty different from the typical Flash game – it’s an adventure game that requires a lot of reading, it’s story-driven, and it’s meant to teach. Which is why we were blown away by the amount of positive feedback we received. But while some players liked our story, our characters or our visual style, the real reason I think of Socrates Jones as a huge success is comments like these:

“It actually does a wonderful job of teaching critical thinking and philosophy as well as just being fun.” -FugitiveUnknown

“I love how it makes it so easy to understand some of the most complicated theories in moral philosophy while maintaining comical elements.” -noandpickles

“I feel that if the education systems tried to present more material this way, people would absorb it alot easier.” -Nogixoxo

We didn’t advertise Socrates Jones as educational, yet a large number of players picked up on those elements and liked our game more because of them. Though we intended the game to be a learning tool from the start, we approached it from a game design standpoint rather than an educational one. Here is a bit about the process we went through.

Teaching through Mechanics

When I hear the term “educational game,” I immediately think back to Jump Start 5th Grade, in which I once solved many a division problem to unlock a door. I often played these kinds of games growing up – adventures occasionally interrupted by “learning.” The idea is that the “fun” parts keep you motivated enough to get through the boring stuff.

Anyone else remember this?

Whether or not they were effective, these games framed learning as a necessary evil that players had to suffer through to earn their fun. I don’t know how much the edutainment scene has changed since I was in 5th grade, but I still see a lot of scoffing at the concept. My sense is that a large number of people are wary of anything that tries to trick them into learning.

But there is another perspective on games as teaching tools – one described by Raph Koster in A Theory of Fun for Game Design almost ten years ago: “Fun is another word for learning.” At least one aspect of fun arises from understanding and mastering systems. We get better at games by poking at and learning the systems that drive them. From this perspective, the notion that learning isn’t fun makes no sense; games already teach us something. The question is how useful that something is in the real world.

It turned out that combining Ace Attorney mechanics with philosophical debate lent itself very naturally to teaching through a system. Because at the core, those mechanics are about conversation, we were able to refine them into a system that modeled a very real, everyday skill: debate.

The goal of Socrates Jones is to use the Socratic Method to find problems with an opponent’s argument. Instead of using a contextual dialogue tree, we give players three questions which they can ask about any statement in an argument:

Can you clarify what you mean?

Can you provide supporting evidence for that?

How is that relevant to your conclusion?

As in the game, these are questions we can ask of anyone making a statement. In a real debate, they cover most of what we might want to know when we apply them to specifics. The skill – in the game and in real life – comes from knowing when to ask which question. Socrates Jones encourages players to explore arguments by asking questions, putting them in the frame of mind to analyze real-world arguments.

These options are always available

Understanding as a Goal

So we made a system that kind of models debate. But that wouldn’t have meant much if the system wasn’t interesting or fun to interact with. This is where blatant theft enters the picture.

It’s no secret that we borrowed a lot from the Ace Attorney series. In addition to the overall structure of questioning and objecting to specific statements, we copied a good chunk of those games’ atmosphere. Much of the fun in Socrates Jones comes from the ah-hah! factor of discovering a flaw and drawing attention to it. We have upbeat music that plays when Socrates tears an argument to pieces, and “nonsense!” is our “objection!”

But Socrates Jones isn’t about tearing down lying criminals masquerading as witnesses. At its core, it’s about understanding. Early in the game, the player is tasked with finding the true nature of morality and confronted with a queue of philosophers claiming to know it. We never give the player an “I accept this argument” button, implying that each answer is in some way flawed.

The player is able to point out flaws in an argument by presenting counterpoints. While counterpoints in a real debate could come from anywhere, we mostly let players draw counterpoints from their opponents’ arguments.

For the purposes of teaching, this ended up being a good decision. Because most counterpoints come from the arguments themselves, many of the flaws arise from internal contradictions in opponents’ logic. Looking for problems within arguments forces players to understand those arguments inside and out rather than trying to bring their own views into the picture. We believe this encourages players to listen critically – a skill sometimes forgotten in an era overwhelmed with vocal opinions.

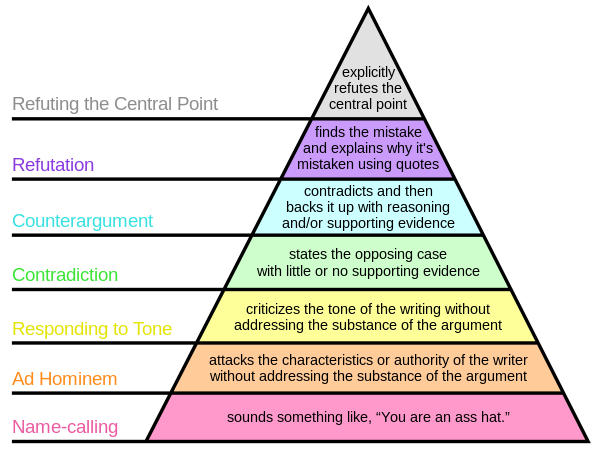

All of the arguments we allow players to make against their opponents fall into the top three tiers of Paul Graham’s hierarchy of disagreement. We also give players the option of name-calling the opponent at any point, but doing so always lowers their credibility, bringing them closer to losing the argument.

The full hierarchy

In Socrates Jones, most of the opponents are based on real historic philosophers who present their actual views. The flaws in those views are based on actual criticisms. While Ace Attorney players are tasked with learning the details of a fictional crime, ours must understand and internalize ideas taught in Introduction to Philosophy classes to progress through the game.

I think this is where the true strengths of Socrates Jones lie. Playing the game and learning philosophical arguments are closely related. As long as players are motivated to put in the effort and think through the arguments, they will likely understand and remember them.

The Role of Narrative

Speaking of motivation – we wanted to believe that our mechanics were inherently fun, but we knew that Socrates Jones was not without its problems. Since much of the game involves reasoning, we could only do so much to push players toward answers without giving them away altogether. As it turned out, our narrative ended up going a long way in keeping players’ interest.

While the story in Socrates Jones was never meant to be the main driving force, we wanted it to be compelling in an Ace Attorney way. It took much iteration, but we ended up with a high-stakes story full of quirky humor.

Using real philosophers in our game worked out particularly well because many of them were already interesting people. We were easily able to distill some of their more outstanding traits into memorable caricatures. Our hope was that by playing their idiosyncrasies for humor, we would help players remember the philosophers (and their arguments) long after they were done with the game. We added a final educational layer by giving some context about each philosopher and weaving his actual quotes into the dialogue.

Finally, we tried to use our story to address one of the inherent dangers with treating debate as a game. We didn’t want players to adopt a sense of superiority from winning arguments and take that into the real world. Instead, we wanted them to be open-minded and question their own opinions along with everyone else’s. “Question everything” became one of the central themes we explored by taking Socrates on a rocky journey from hopeless sheep to skilled debater.

If you want to know the context, you'll have to play the game!

Conclusion

We’re really proud of how well these elements came together. At the time of this writing, Socrates Jones has been played almost 200,000 times on Kongregate and is somehow maintaining a 4(of 5)-star rating. Despite being educational, it was the second-highest-rated game uploaded in August.

But more than anything else, we’re proud of hearing from players who didn’t expect philosophy to be fun or interesting. Many of them have said that they are picking up philosophy books for the first time because of our game.

As with any other genre, I don’t think there is a single “best” approach to designing for educational games. But I think we can do some really interesting things if we stop assuming that learning is inherently boring.

If you want to hear more from us, you can follow me and Connor on Twitter.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like