Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Github has done a phenomenal job at making Git the law of the land. But when it comes to version control systems, Git is not always the right answer.

April 10, 2017

Sponsored by Assembla

Author: by Jacek Materna, CTO, Assembla

From managing software development teams to being a game development hobbyist, I understand how version control systems are used for different jobs and why. My developers work both in Git and SVN but on the gaming development side, Git is not always the right answer.

For this particular post, I’d like to take a deep dive into why Subversion is a great version control system for game development. This post is not meant to create a flame war between DVCS and non-DVCS as Git is a preferred VCS for most software development tasks out there today, just not all.

Github has done a phenomenal job at making Git the law of the land. It was able to do what many companies failed to do with other competing technologies by corralling a community around a certain way of thinking, building and storing text based source files. It was immensely successful at spreading the Golden Hammer model of version control for all new developers. As Maslow said,

"I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail."

This is a fundamental problem with the conversation around version control; it quickly becomes a religious debate versus looking at the practical reasons and questions around what the best tool for the job is.

I’ve been in plenty conversations that lead with “So [repo technology] is really good for developing in Node.Js so it’s great for developing xyz, right?” What’s happening is that developers are taught in college, or maybe it’s a company culture, that because Git is the best choice for one thing, it’s the best choice for everything. After all, not all version control systems are created equal.

For game studios, although many use distributed VCS, most don’t and there are clear reasons on why, based on their workflow or even type of game. So why use Subversion when developing games? Let’s get into a few interesting topics in and around this central thesis.

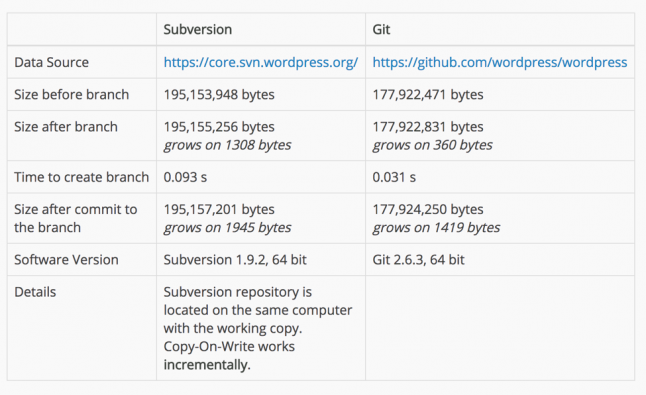

Remember the good old days when Linus was secure copying tarballs to kernel.org for years while Git was the new hotness on the street? Why was he doing that if Git was in play and could merge release branches with ease? It’s because his particular release workflow was done better and cleaner without branching. That’s OK! Bottom line is that just because a tool can merge well doesn’t necessarily mean game studios need to merge a lot; it’s a subtle difference. Game workflows are different and they come in all sorts of flavors. Subversion is actually great at merging, it’s lightweight and fast, but that’s not really the point here. On the notion that Subversion is not good at branching and merging, take a look at this example data from svnvsgit.com on the common “it’s too fat” comment.

There is no practical difference. The moral of this story is that choosing a tool based on it’s merging prowess when merging is not a first class citizen in your workflow is counterproductive. For example, Subversion is a hammer you want use to solve real challenges in game development like how to handle big files.

One of the biggest challenges Git users have faced is the poor management of large files. Git simply falls over after 1GB for a repo which is why developers create more repos and split the code into a web of repos. Games have lots of binary assets ranging anywhere from a few Gigabytes to many Terabytes so this is a major obstacle for game developers. One of the solutions to the big files problem is Git LFS. It was designed to bandaid the architectural limitation of Git as a DVCS around binary files. Git LFS is definitely an answer, but it’s an answer to a problem created by Git.

Another solution to the big files problem that I’ve seen, is to use Git for code and Subversion for assets. While it’s a solution, is it really an ideal one? At some point you have to ask yourself: if you have to implement a separate solution for binary assets, maybe I'm using the wrong version control system?

Another solution is to add your assets to a file storage platform like Dropbox. I’d like to reiterate the central lesson in this article: versioning your assets separately then your code is a terrible idea. Using an add-on like Dropbox is a solution, but is it really a good solution for the awesome game your amazing team is building?

Aside from the proposed solutions, I’ve seen a lot of chatter on many Reddit forums that quote, “you shouldn’ be committing game assets to version control.” These comments really highlight the mentality that all developers are created equal. In a lot of ways, this really hones in on exactly what makes game development different than general software development. Game assets and code should be one. Code is tightly coupled to data in games, and that’s not a bug. Splitting them is a disaster when it comes to real world game development pipelines.

Games by default will have a lot of characters, models and images - way more than source code in many cases. Assets are by their very nature non-mergeable. Git, Subversion and a lot of other repo technologies use what is called the copy-modify-merge model. Essentially this model assumes everything is mergeable. Unfortunately, this model has zero value for assets that can’t be merged. So why would you use anything except a tool which can support both?

Git has no locking. Subversion has had locking native for years. If you need to work on a character and don’t want a member of your team to touch it, you can easily get the file, lock it, work on it and only when you’re done, commit it and unlock it for others to get the new version.

This process represents 90% of the workflow that technical animators, artists, engine programmers and the like do when building games in a project pipeline. There are a number of developers on a large team which spend their entire life in C++ and Visual Studio but let’s remember that they’re part of a larger team. The version control system for the team should cover all cases, not just the minority and this is where Subversion reigns. SVN has locking built in, and it’s intuitive for all users especially when coupled to a native app like Tortoise SVN.

For game development, never ever use a VCS that has no locking natively built in. Your creators will thank you later!

Humans make mistakes all the time, it’s impossible to prevent. People will do things like commit 300MB zip files to version control (and of course all the files in the zip next to it) having everyone download that zip forever and ever in a DCVS because it’s now stuck forever in the history. It was never designed for this use case. The Linux Kernel was thousands of text files managed by a lot of people that may not have had any connectivity to each other until “the very end.” I call this private or non collaborative development. It’s roots came from this model.

On the contrary, Subversion is the most collaborative version control system out there. It was designed around the concept of monolithic repositories and central collaboration. For example, some of the advantages of the use of monolithic repositories are:

Better code visibility

Atomic large-scale refactorings

Better dependency management and collaboration across teams

In fact, companies like Facebook and Google, who have the largest codebases on the planet, still use the monolithic model.

DVCS users see having the entire repository locally on their computer as a great feature. It helps with redundancy and backups in the event data is lost. Likewise, it’s great that you can commit immediately and it’s super fast (because it’s local to your computer). When you’re grabbing someone’s mega ZIP of stock image textures, shaving a few seconds off a commit is like shaving 30 seconds off a marathon time for a novice runner - it doesn’t matter.

When using a DVCS, the expectation is that you have the entire repo for that module/component you’re working on. If you have a 100GB repo then this means you have a 100GB checkout on your hard drive. If you’re using Subversion you just have the current checkout. If the current version or even subset of the current version (i.e. Checkout only the folder you need) of what you’re working on is 2GB then that’s what you pull down. Do I need everything? Likely never but I can grab it all if I want.

Game development has some of the most heterogeneous teams out there. You have artists, animators, developers, designers, producers and directors. Technical and non-technical personas alike. It is super important that choosing a Version Control System is not done in isolation. Even Subversion, which in my opinion is a great VCS for game development, is just a repo. A real team needs a way to manage tasks, communicate (Slack for example), conduct code and asset reviews and needs everything to be tracked together easily in one platform to ensure your team can work as effectively and efficiently as possible which will enable you to ship your game on time.

Don’t just get a Repo and plan for collaboration later in the project. Bake the decision in at the same time. Your team will thank you for it later.

What type of game would make DVCS a good choice?

When you have a tiny game with no intent of growing large, small mobile apps for example.

Your art assets are minimal. Pixel art, procedural assets, or a text adventure.

It’s just you on the game - who cares what happens to the history? Good luck!

Your ENTIRE team knows DVCS like Git - that means not just the few developers. The team including developers, artists, designers.

When is it bad choice?

You’ve got a lot of assets (which is pretty likely!) if you’re making a modern game in 3D or even a complex game in 2D.

You have non-technical users who need access to the project.

Subversion is fast, secure, reliable and just works for game development. Not all software development projects are the same - it’s ok to have different hammers.

Happy game building!

Jacek Materna

CTO

Assembla

Read more about:

Sponsor Resource CenterYou May Also Like