Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What goes into writing for a game without a linear narrative? A lot, say Valve and Madden veterans, who explain the keys to writing for games which will be played again and again.

What goes into writing for a game without a linear narrative? A lot, say Valve and Madden veterans, who explain the keys to writing for games which will be played again and again.

Games need writing. We often think of game writing as exclusively related to storytelling, rooted in Aristotelean maxims of time, place, and prescribed resolutions, which makes it hard to see the value of writing in games without a single player story mode. But for many games the art of embellishing play with writing has helped add depth and drama to systems that might otherwise have seemed pointlessly repetitive or cyclical. Even without a single story to tell, writing can be an essential creative tool for games that would rather be about fun and competition than allegories and plot twists.

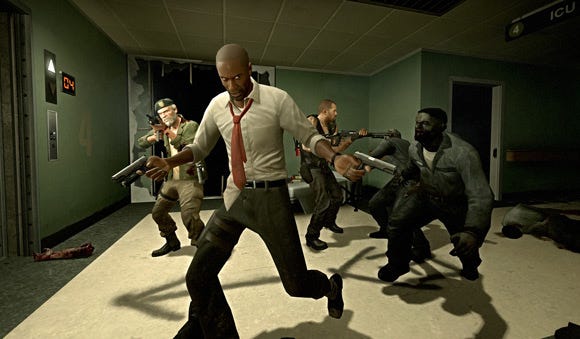

Valve's Dota 2 is an ideal balance of written characterizations and lore, which merge with a system of competing against other players in perpetuity. The Madden series has made particular but effective use of writing for years, adding small bits of contextual flourish to a dropped pass or a missed career mode goal. Valve's Left 4 Dead games merged an infinitely replayable multiplayer shooter with lush interpersonal drama written into each level.

In these cases writing is less storytelling than a tool that enables players to tell their own stories, using the context and plotted consequence chains planned for them. They represent a model for dramatic interaction that can be applied to many different games. The point is not to weave a particular story but to characterize the available choices and consequences for players in a way that takes them beyond simple mechanism, something as applicable to multiplayer shooters as it is brain trainers and exercise games.

Valve's Dota 2 has many of the same elements of a traditional story game, yet they're left in an unassembled state. It doesn't aim to tell any one particular story but instead dramatizes and deepens the player's experience within each round with artfully deployed writing.

"I don't feel that Dota 2 is a narrative game in any sense -- not even in an open sense," Valve's Marc Laidlaw said. "It doesn't feel like a narrative to me because there is no possibility of development. It starts and ends the same way every time, with only two possible outcomes, although the various ways of reaching those endings are infinite. We might compose some bits of narrative around it, such as the comic, 'Tales From the Secret Shop,' but no sort of recognizably narrative thinking goes into the way we write dialog."

"We do try to identify a moment or turning point in a hero's background that would have been the key moment that thrust them into the spotlight and made a hero of them. But that moment is always somewhere in the hero's background. We assume the big personality-shaping crisis for each individual hero is somewhere in their past. The game itself is more of a crisis for the entire world and every hero in it, it's less of an individual's story."

According to Laidlaw, 95 percent of the energy spent on writing Dota 2 went to dialog, a process which begins by working with the game artists to understand the visual design and broad personality types of each hero.

"One of the tough parts was coming up with a few hundred lines for each character when each hero has only one or two major traits," Laidlaw said. "Initially this led to a heavy reliance on -- ahem -- well, some would call them puns, others would call them motifs. In a lot of cases, these themes were our lifeline -- they were the only thing we had to work with when it came to distinguishing one hero from another."

"Over time we have gotten better at making our dialog thematic without making it simply groan-inducing. This is the result of both practice and of growing confidence in the role of lore, and how much of that can inform the moment to moment responses a hero can make to player clicks. What surprised me a little is that it has gotten easier to write dialog for the same repetitive categories of responses; you would think that after 90 heroes, it would be impossible to find more ways of saying, 'Onward!' or 'I go!' But in fact we usually have enough new ideas that we almost never feel compelled to repeat old ones."

Dialogue in round-based games like Dota 2 can also cue the player to how they're performing. "Feedback is the core of a good experience, and the way in which you provide that depends upon the hero," Laidlaw said. "Some heroes can easily turn and address the player without breaking out of character; others are too serious, too much a part of the world, to do something silly like that, but they still have ways of letting the player know their decisions are meaningful."

The RTS game Majesty was an especially helpful reference point for Valve in modeling just how iconic dialogue can enhance gameplay. For a while Laidlaw wondered if they might actually hurt the overall experience by adding too much dialog. "I was worried that having too many lines per character would dilute the impact, and make it less likely that any one line would become iconic," he admitted.

"This turned out to be less of a concern because so many people play Dota 2, for so many hours, and in so many possible combinations of characters, that even its great variety effectively gets ground down to a small set for any one individual. Each fan can still connect to a few favorite iconic lines, even if they're different for everyone."

Having announcers in the game also adds an element where players can control their own preferences for how chatty the game will be. "We are starting to add custom announcers to the mix, and because these voices sit somewhere above the world of the game, they have the chance to address the player directly -- as well as talking down to the heroes in the game," Laidlaw said. "We're just starting to play with that, and we are already seeing fans creating their own announcers. I think we will see a lot of fan-made announcers talking directly to the player. It seems to be something people want."

Approaching the development of the game's written elements in this way provided a natural opportunity for Valve to involve series fans into the development process. "The toughest part is working with a set of characters with whom the Dota community has such a long and lasting relationship already," Laidlaw explained.

"We are simultaneously creating and recreating characters. The fans love and appreciate and even demand originality, at the same time that they want clear and faithful connections to the heroes they loved in DotA 1. In some cases this is fairly easy to achieve, in other cases it is just impossible. At this point we have started erring on the side of creating our own universe, but it took us a while to feel confident in doing that, and that the fans were truly open to this."

For Madden NFL 13, EA Tiburon has embellished their already sprawling Superstar Mode with between-game Twitter commentary from real world sports reporters and analysts. As a simulation of a professional sport, Madden enhances its drama by attempting to mirror the post-game analysis and opinion-jockeying that accompanies the physical sport. In addition to playing for stats and league position, one feels the sting of pride when being hectored in public by a familiar persona, or else enjoys the prideful satisfaction of having made an infamous curmudgeon say something nice.

"We really wanted to capture each person’s Twitter usage accurately, so the early task was to figure out was what did each person talk about," Mike Young, Creative Director at EA Tiburon said. "Adam Schefter focuses on breaking the news about signings, trades, and things like that in a very dry way. Some personalities are opinionated about the news. Others, like Todd McShay, mostly talk about draft prospects."

"Then we had to figure out how each personality actually translates on Twitter. Do they use exclamation points, hashtags, all caps? Do they talk about a certain team more than others? Are they snarky, corny, witty? Mark Schlereth talks about his chile company all the time. Studying them really was the key to making it as authentic as possible."

With a reasonable sense of how each of these people appear through the keyhole of Twitter, the focus shifted to a question of scale, creating characterizations to address the huge number of possible situations that come up during a 30 year Superstar Mode.

"So many permutations can happen in our game, so it is a real challenge to cover all the scenarios and not be repetitive," Young said."Often we would find the real Tweets for similar situations and use that as inspiration.For example, we would see something like Curtis Martin elected to the Hall of Fame."

"Skip Bayless said 'he had to think twice' about him going into the Hall of Fame. How do we make our Skip Bayless say something like that about a similar player? When we were done with the scripts the media personalities reviewed the content and gave feedback. For a couple of the personalities we were able to show them the feature in person which really helped."

The story in a given playthrough of Superstar Mode can be almost anything: the underachiever, overachiever, the veteran who couldn't face retirement, the journeymen who went from team to team, or the mythic legend who changed the game forever. The addition of Twitter is not meant to favor one over the other but to deepen the emotional context of each choice the player makes for themselves.

"For any one event it will be factoring in a ton of criteria," Young explained. "Is the player a former high draft pick?A future Hall of Famer? Age? A starter? That way when something like an injury happens we can be pretty specific. So if the event happens to Tom Brady it will feel like a much bigger deal than if it were Kyle Orton."

"That brings to the surface things that you wouldn’t normally hear about. It makes the world feel real, the players feel special. I actually felt sad when Ray Lewis retired in the game because of how we bring it to life. Seeing the entire Twitterverse talk about his career and if he is a Hall of Famer or not makes it much bigger than a digital guy disappearing from the roster."

Before turning its attention to the Dota revival, Valve re-conceived the multi-player FPS with the two Left 4 Dead games, combining the manic intensity of competitive shooters like Quake with the lush story atmospherics of Half-Life. The games are ideal examples of how, in moment-to-moment experience, a perpetually replayable game, multiplayer or otherwise, can be as full of drama, character, and emotion as a traditional single-player story game.

As with Dota, a huge amount of the emotion in Left 4 Dead comes from character dialogue that must both comment on the immediate objectives and hint at a larger story. "We never try and say everything in one playthrough, because we know people will play the same campaign multiple times, so we can leak out bits of story each time," Valve's Chet Faliszek said.

"For campaign specific lines, we go through the maps and mark up areas for the players to mention or to talk about. We can control the chance of them speaking when they see it and how far the player can be from the object before they speak. So for the maps of The Parish, if you get Coach close to most signs and look at it -- he will often read it. Other times you will notice, characters will talk about a plot point -- these bodies don’t look infected -- when they are in a general area."

The games' flexible approach to dialogue most not only hint at broad narrative pieces but account for momentary circumstances that aren't necessarily broad or narrative. "Other times we take that piece of data and then compare it to other data," Faliszek said. "If Nick is going to talk about a horse -- is he by the statue? Is Ellis alive? How close is Ellis? Are they out of combat? All of these conditions help control how often a campaign specific line will play. So while there may be fewer of them, the campaign specific lines end up taking the bulk of the work."

"'Clever' lines can become tiresome if you hear them too often, but if you choose to only have Nick make a comment about his suit while in one map and only 10 percent of the time -- players won’t become irritated by the line. We also always make sure the characters are saying something, if nothing else at least, 'reloading'. This gives a bed for all the lines to live in and become part of the world. That way the story points don’t stick out of the silence."

The AI Director was a major part of what made Left 4 Dead so replayable, creating new spikes in difficulty and varied enemy encounters throughout each level. It might seem like the technology could have been applied to the game's dialog system, but Valve discovered it was actually important to keep the AI Director confined to combat.

"We never link the lines to actual Director code because players play for hundreds if not thousands of hours, they would learn what those warnings meant and be tipped off to what is next," Faliszek explained. "To keep players in the world, your character only knows what you know about the creatures around them."

"We do use the Director to give us a clue on one state; what is the player’s intensity level. We often use that in conjunction with health and other states to pick a line. You can get away with saying a quiet line in a loud situation but it doesn’t work when your character is screaming at high intensity while the character is experiencing a low intensity situation."

Valve was likewise careful to not use dialog to comment too directly on player performance for fear of breaking the dramatic illusion built up with the environments and characterizations. "Guessing intent is really scary and something we try and avoid," Faliszek said.

"We also try and not break the fourth wall with dialogue, but the characters do react to friendly fire and often offer suggestions like use a health kit or pills to other players as a way to bring attention to a character state. Coach will even actually 'coach' other characters to hang in there when they are injured."

Another major concern for games that stitch together thousands and thousands of lines of dialog, plot, and characterization on the fly is how to blend lines together without them sounding disconnected. "While it may sound like fragments, we actually record various versions of a paragraph worth of text and then programmatically piece them together at run time," Faliszek said.

"If the audio is going to play right next to each other, it is always worth picking up the duplicated audio in each take just so the actor flows with the various versions. Sometimes we need to use the entire take and sometimes we can just use the various stubs. To make sure it will work we test it outside the game and then we play through with a setting to force the audio to play so we can test even the rare occurrences. For the 10,000-plus lines of dialogue in the game, I have probably heard each one 50 times by the time we ship."

It has been easiest to understand game dramatics in terms of film and novel, plots and progression serving as structural pillars in between constrained arenas of play. This structure has a kind of baroque purity that distinguishes its two parts: here is the story and here is the game. While the two compliment one another, they are essentially counterpoints that must play against each other.

There is nothing inherently bad about this approach to game design, but there are many other possible forms, many of which have no particular need for story but which can still benefit from writing. In the same way that Tetris benefits from music and art even while it cannot be called a symphony or a great painting, there is a world of expressive possibility that can come from writing, even when it does not intend to be taken as a traditional story.

"We've just scratched the surface with reflecting the personality of players," said Young, regarding Madden's Twitter embellishments. "We have stories about players and teams being far apart during negotiations or players being on the trade block, things like that. There are still plenty of ways for us to expand this feature down the road by giving you a way to have a voice."

Games have the extraordinary capacity to combine all of these creative forms -- the dramatic, visual, auditory, and performative -- into an amalgamated whole. In the rush to find a set of best practices it's often forgotten that what defines "best" is relative. Instead of thinking about formal restrictions that must be adhered to, it would be more productive to imagine all the things you might do with the rich palette of tools available.

"I've always felt the strength of the game industry is the staggering amount of variety in types of games, the fact that there are games to suit every possible interest," Laidlaw said. "I've also always felt that good games can be made even better with good writing, even if that is not the game's real emphasis, and that entertaining writing is appreciated no matter where it appears."

"I never felt like we ought to work any less hard on our dialog just because the game is not a narrative one. Valve is known for creating great characters, and we didn't want to compromise any of that just because this time our characters were these tiny little critters you mostly saw in a top-down perspective."

Games do not always have to be about storytelling but it is hard to imagine them without the art of writing, from Rock Band to Wii Fit and from BioShock to Madden. Writing can help give depth and context to a system that might otherwise be a flatter and duller arrangement of rules for the purpose of determining a winner and loser. It's the human in the system who finds the distinction between winning and losing so dramatic. Writing can be a powerful tool to make that person return again and again to a game, whether it's because of the subtle encouragement of a trainer, or the arch cries of a mystical hero in the heat of combat.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like