Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The Relationship between Engaging Games and Mental Health

Every time I seen an Xbox 360, I turn 360 degrees and walk away. Why? Because I feel nauseous when looking at the rapid leg movement in Street Fighter, overwhelmed when I am being chased by a hoard of zombies in Left 4 Dead, and particularly dizzy when I am witnessing what is derived from the social community in Call of Duty as the internet-famous “360 MLG No-Scope”. There are too many actions occurring at the same time, to the point where I am feeling distressed. I feel the need to stop, take a deep breath, and find some other task to do that is not as demanding physically and mentally. Video games should be a source of entertainment, joy, inspiration, and comfort, not some burdensome task that takes away from our happiness. This article will examine the relationship between stress and engagement in games, the impact stress has on different players, and the way good games are designed based on the foundation of eustress.

Stress and the Player

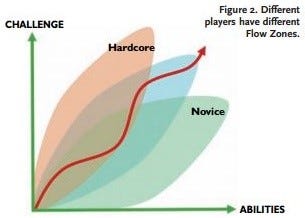

When multiple people are asked to recall a stressful, anxiety-inducing game they have played, many of their responses will vary. Video games do not generate stress alone, but rather it is the player’s own interaction with those games that results in an overwhelming, or even underwhelming, personal experience. For instance, a veteran player who has been gaming since the retro era of the 20th century may find a shoot-em-up game like Doom soothing to their preferences. From the rhythm of the gunshots to the pacing of the footsteps, this gamer is at harmony with their play experience, often losing themselves in a world they are so much engrossed in exploring. On the other hand, a novice player may also pick up a copy of Doom and immediately find themselves confused as to how the controls work, what the complex series of icons on the user interface are supposed to represent, and why they are suddenly dead. This player may try to play the game again and end up dying over and over, resulting in frustration and a disinterest in continuing game play. A player’s skills may be the verdict for whether a game is or is not an appeal to them.

As games are associated with rating systems and different genres, players are also categorized based on the abilities and assets they bring to these games, which ultimately affect their game play experience. One simplistic classification of gamers as casual and hardcore players is described by Jesper Juul in his novel A Casual Revolution (2010). In examining players of different skill levels, Juul stereotypes hardcore players as those who invest a lot of time and resources into the games they play. These games tend to challenge the player’s extensive skills and are often too difficult for casual players, whom Juul stereotypes as those who are willing to commit little time and few resources towards playing games. Many games tend to be out of reach of the casual player’s level of skill, but while this is the case, there are still many games that will match their play style, as there are rigorous games fit for only the toughest of the tough.

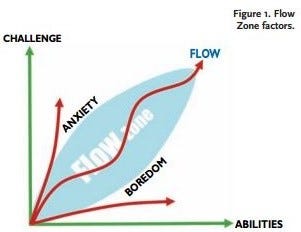

The games that best appeal to each player generally align with their skill set, creating a balance of challenge that is not too easy nor too hard, but rather is at a harmonious equilibrium in-between that encourages and enables the player to engage in the game they are playing. This immersive experience is known as flow, a term coined by psychology professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, which “represents the feeling of complete and energized focus in an activity, with a high level of enjoyment, and fulfillment” (2002). Players in a flow state will often forget about their surroundings in the real world, as they are so absorbed into the task at hand within their game. A player remains in a flow state as long as they are continually being challenged at an appropriate pace; a player will leave the flow state if the challenge is too hard, resulting in frustration and an increased level of anxiety, but they will also leave the flow state if the challenge is too simple, resulting in a loss of interest (Chen, 2007). A lack of stress can result in boredom and loss of motivation, while too much stress can

(Diagrams by Jenova Chen)

cause the player to suffer from anxiety. A person’s mental and physical well-being can be affected by stress, so it is important to keep it at a balanced level. Stress energizes a person’s mentality to both think and act − two crucial skills that are tested not only in games, but in real world every day applications. A game positively serves its purpose as a valuable artifact and an influential health device when it allows a player to ease into the flow mentality.

Aesthetics of Stress-Relief Games

With the rise of the technology revolution in the 21st century came the rise of online social networks, innovative computer technology, improved artificial intelligence, billions of mobile apps, the Oculus Rift, and giant robot sharks (a boy can dream right?). There was also the demand of skilled labor to meet the needs of an ever-technologically-advancing society, and with this demand came higher expectations in professional matter, heightened competition in schools for a shot at the Ivies, and even increased productivity in one’s own household. With all of these pressing expectations from society, stress is surely bound to snowball and become a massive burden on our ability to complete daily tasks. One solution to reducing stress was through the adaptation of casual games into society’s norms and values. As of 2009, there were “more than 200 million casual gamers worldwide” (Russoniello, O’Brien, Parks). Not only were more people playing these games, many of them were seeing reductions in stress levels. The Casual Games Association conducted a survey of gamers in 2006, and the survey found that over “88% of respondents derived stress relief” (Russoniello, O’Brien, Parks) from playing casual games, demonstrating how casual games can remedy anxiety.

One profound casual game that has reached out to me personally is Flower, developed in 2009 by Thatgamecompany and coincidentally designed by Jenova Chen (whom I mentioned previously in the Flow section) and Nicholas Clark. The objective of this game is straight forward: the avatar is a single petal; the player controls the wind; the player must guide the petal across luscious landscapes, collecting more petals in the process. At the end of the level the player enters a swirling vortex where the petals disperse across the land, purifying it from the corruption of man’s careless waste.

Level 1 from Flower: "Life as a Flower"

Flower is designed primarily to address audiences suffering from anxiety and depression through spiritual healing with nature. Having played this game myself, I recall experiencing an exhilarating rush of joy, freedom, and motivation to explore the game’s space. I felt empowered by the idea that I was curing the environment, as if I had a significant impact on the world and had served my purpose in life. My stress melted away as I was engaged by the positive values and motives within the game.

Aside from my view, there are many other interpretations and metaphorical constructions of Flower’s message. Marientina Gotsis is a Research Assistant Professor specializing in applications of interactive entertainment in health, happiness and rehabilitation, and her stance on Flower concentrates on the correlation between nature and happiness:

“In the past, we tried to improve our health by segregating ourselves from nature. This plan has backfired because humans are inescapably embedded in nature. Technology has sheltered us from the storm, and science has healed some of our ills, but in doing so we seem to have contributed to nature’s demise, which in turn has affected our health and happiness” (Gotsis, 2009).

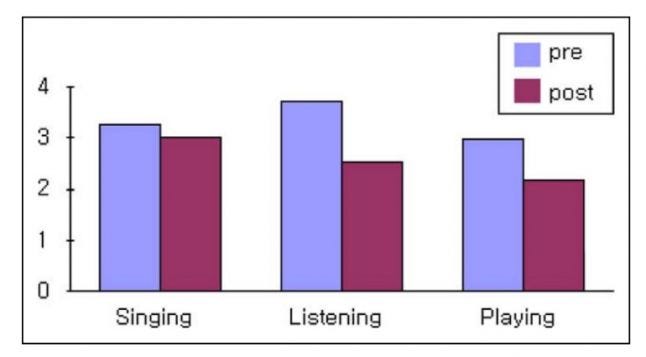

The concept of Flower has led to many inspirational ideas on how to improve society has a whole. Not only does the game contain a compelling player-driven narrative, the aesthetics are strongly reinforced by the beautiful visual scenery and, in particular, the audio. Music therapy has been seen as an effective method of reducing stress. In an experiment, researchers Eun-Young Hwang and Sun-Hwa analyzed the emotional status of individuals before and after music therapy. These individuals consisted of Alcohol-Dependent Clients that had been suffering depression.

Average Score of Anger by Activities (Diagram by Hwang and Hwa)

After a series of music therapy sessions, Hwang and Hwa discovered that the largest decrease in stress was from after listening to relaxing music ranging from the classical genre of Vivaldi and Beethoven to smooth jazz and even to some rock and roll from the Beatles (2013). Similarly enough, the soundtrack in Flower contains many meditative wind and string instruments accompanied by a lone piano, all of which, along with the vivid visuals and empowering narrative, serve as a foundation for a stress-free environment. Casual games are not simply small past-time hobbies that can be ignored, they are necessary for social and mental recuperation in a harsh unforgiving world.

Level 4 from Flower: "Nighttime Excursion"

Aesthetics of High-Energy Games

Why was F-Zero GX given the name it has? Because there is a zero percent chance that any normal person would beat this difficult game! As opposed to a laid back game like Flower, F-Zero GX exemplifies an intense game requiring skill and strategy in a demanding environment. Nintendo published this game in 2003, and it is still one of the few games to date that I personally own and have not been able to complete (and that is saying a lot, not to brag). It is a game that revolves around racing fast cars in dangerous environments that consist of lightning storms, giant boulders crushing everything in their path, and even flaming lava pits of death. Not only is the game environment intimidating for a casual player, the entry level into this game is extremely low.

A shot of Captain Falcon racing on the track "Fire Field"

The campaign mode of F-Zero GX is notorious for its sharp difficulty curve. The player begins by taking on the role of Captain Falcon in his training simulator, where they are given the objective of collecting a certain number of items on the presented racetrack in a limited amount of time. If the player does not collect enough of these items, as well as pass the final lap within the time limit, they will fail and have to retry the course again. Very quickly will the player realize that they are being asked by the game to perform many tasks at the same time, and the pressure does not stop there. Once the player completes the course on the normal difficulty, they have to complete the course again on the harder difficulty, and only then will they be able to progress to the second level of the game. This game only has three difficulties: Normal, Hard, and Very Hard (which I recommend avoiding). Indeed, there is no Novice difficulty, for the game is targeted towards more skilled players who can handle situations a casual gamer may find too stressful.

While the gameplay itself is demanding, the culture embedded within F-Zero GX is also demanding in the sense that it reflects the competitive nature of the real world. Racing within the game is viewed as a worshipped practice and the only valuable commodity life has to offer, as made fact by the existence of omnipotent Racing Gods that oversee Captain Falcon’s races (the story line is rather cheesy). Racing is not simply a sport of entertainment, but rather a demonstration of status and power over one’s adversaries in the form of deep play (Bentham, 1840). Symbolic anthropologist Clifford Geertz adopted Bentham’s concept of deep play in his Notes on the Balinese Cockfight, describing it as a form of “play in which the stakes are so high that it is…irrational for men to engage in it at all” (1973). Cockfighting to the Balinese villagers is a game of high stakes involving not only bets of money but also reputation and social status. The social hierarchy in this village revolves around the man with the dominant cock, just as to how the most glorified racer in F-Zero GX is the character who dominates on the track. These racers could die during the race, and the fact that they are putting their lives at stake for social status really emphasizes the value of racing in that game’s culture. A lot of pressure is put on those characters to rise up to the expectations of their own society – pressure of which gets converted into additional stress for the player to not let their avatar down.

F-Zero GX is an intense, energetic game that caters to hardcore audiences. These players are not overwhelmed by the level of skill required, yet the challenge the game has to offer is still difficult enough to engage these players, keeping them in the flow state (Chen, 2007). Such a fast-paced game would, however, generate anxiety for casual gamers and have a negative impact on their gameplay experience, resulting in frustration and possibly depression. This may seem trivial, but it is important that the player understands what category of games they enjoy playing and what type of game they intend to play so that they can maximize their happiness.

Conclusion

When thinking about game design, try thinking first about what emotions you want to evoke in the player, then build the game world around that concept. The target audience for that game, and any game in general, is the category of players who respond accordingly to the game designer’s intentions, and if that game designer is engrossed in the game they are developing, their audience will likely be engrossed in the game as well. Video games are meant to be a haven from the stress of reality; they should allow us to free our minds and enter a world of our own desire, providing us with comfort, happiness, motivation, and inspiration to take action and show the world our true potential.

Bibliography

Hwang, E., Hwa, S. (2013). “A Comparison of the Effects of Music Therapy Interventions on Depression, Anxiety, Anger, and Stress on Alcohol-Dependent Clients: A Pilot Study”. Sage Journals. Retrieved from http://mmd.sagepub.com/content/5/3/136.full.pdf+html

Russoniello, C. V., O’Brien, K., Parks, J. M. (2009). “The Effectiveness of Casual Video Games in Improving Mood and Decreasing Stress”. Virtual Reality Medical Institute. Retrieved from https://bioinformatics.ecu.edu/cs-hhp/biofeedback/upload/The-Effectiveness-of-Casual-Video-Games-in-Improving-Mood-and-Decreasing-Stress.pdf

Juul, J. (2010). “A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and their Players”. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=r4vRa7MGbYIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Qualities+of+casual+video+games&ots=7vXJ-Cetr2&sig=wmhgmZUfxrYgA6JdLKpuEHt2c8Q#v=onepage&q=Qualities%20of%20casual%20video%20games&f=false

Chen, J. (2007). “Flow in Games (and Everything Else)”. ACM Digital Library. Retrieved from http://www.jenovachen.com/flowingames/p31-chen.pdf

Gotsis, Marientina. “Games, Virtual Reality, and the Pursuit of Happiness”. ACM Digital Library. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1669324

Geertz, C. (1973) “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight”. In “The Interpretation of Cultures”. Retrieved from http://itu.dk/~miguel/ddp/Deep%20play%20Notes%20on%20the%20Balinese%20cockfight.pdf

Bentham, J. (1840) “The Theory of Legislation”. The North American Review. Volume 0051. Issue 109. Retrieved from http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=nora;cc=nora;rgn=full%20text;idno=nora0051-2;didno=nora0051-2;view=image;seq=00396;node=nora0051-2%3A1

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like