Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"In life, we all learn through failure and not just through success. It was important for our characters to survive these confrontations and face their adversaries again." - Greg Kasavin, Creative Director at Supergiant.

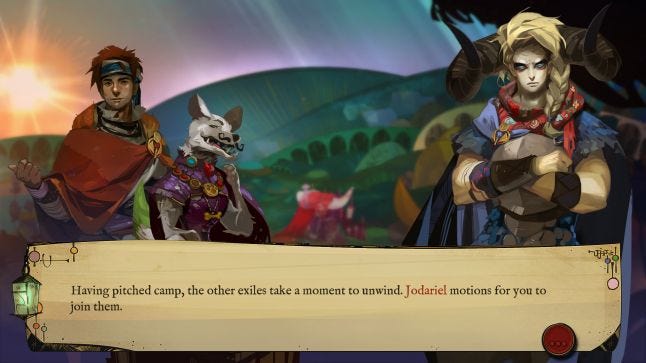

Pyre, the latest from Supergiant Games is something of a departure for the indie studio. Its latest title eschews a single protagonist, the formula that the team successfully employed in previous games Bastion and Transistor, for a team of outcasts forced to compete in competitions in order to win salvation.

The development team wanted to try something different this time around, envisioning a game with an ensemble cast where characters would have to rely on teamwork to earn their way out of the mysterious realm in which they found themselves trapped. It’s also a game with no real fail-state in the traditional sense -- if your party loses a competition, or in the world of Pyre, a Rite, they must dust themselves off and simply try harder next time.

Greg Kasavin, creative director at Supergiant, believes that this system fits perfectly with the inherent ups and downs of competition, and allows for a more natural connection between gameplay and Pyre’s narrative.

“The idea of these characters, their path to enlightenment, their attempt to regain their freedom from this mystical purgatory,” Kasavin says. “It all was very appealing to us because in life, we all learn through failure and not just through success. It was important for our characters to survive these confrontations and face their adversaries again at a later time and have those other characters remember the outcome of their last encounter.”

Of course, abandoning a foundational game mechanic since the medium’s inception is not without its risks. The majority of games we are familiar with have a clear cut win/lose condition. If you take enough damage, or you fail in a task, you must simply start over from a previous stage. Supergiant was well aware that trying something new in this regard could very well backfire.

“We knew that making a game where it would be okay to fail at any point would, if nothing else, make a lot more work for us,” Kasavin admitted.

"In life, we all learn through failure and not just through success. It was important for our characters to survive these confrontations and face their adversaries again."

The team would have to see how they could support the mechanic as a path for players while still allowing for a viable story that made sense. Of course, there’s also the issue of player acceptance. Change does not necessarily always come easily in the video game industry.

“Players are very conditioned to expect to win and they inherently don't naturally feel good about losing,” Kasavin says. “So the game itself bears a certain burden of making players understand that those types of outcomes, in the context of Pyre, are actually okay.”

Yet the team at Supergiant thought the risk was worth it, and were curious to see what would happen.

“We know that some players will just save/load every time until they win, just like in a traditional game,” Kasavin considers. “But we didn't make this decision for those players. We made the decision for everyone else who's willing to have that experience. And we think for those players, it'll be that much more of an interesting experience.”

Before players get to take part in that experience, though, the team had to make a lot of considerations in building this innovative new model. Without a clear-cut fail state, for example, how does the game build tension?

"We knew that making a game where it would be okay to fail at any point would, if nothing else, make a lot more work for us."

“A very big part of the development of the game is making the stakes of these competitions feel high,” Kasavin explains. “We want to set up a situation where the player understands that it's this purgatory setting where all these characters are essentially trapped and competing to regain their freedom.”

The actions the player takes determine who will regain freedom and who will get left behind. That’s no simple task when you’re forming bonds with these characters, both allies and opponents, over time, coming to understand their varied histories and motivations.

“We like to . . . present stories from different points of view and put players into situations where they can make expressive choices,” Kasavin notes. “Not necessarily moral choices, where there's like a right and a wrong decision, but choices where they can internalize whatever the outcome is and feel okay about it. We want for those choices to align with hopefully a wide enough range of what the player might be thinking at the time as opposed to what we want out of the story specifically.”

These expressive choices, and the number of ways a player can fail throughout the game, means that there are innumerable paths the story can take before the game is through. Kasavin says this was an especially challenging aspect of the design process.

“There's a situation we had to handle in the game for most of development. At many points throughout the game, we just don't know who is still there, who is still part of your group,” Kasavin says.

"We like to present stories from different points of view and put players into situations where they can make expressive choices. Not necessarily moral choices, but choices where they can internalize whatever the outcome is and feel okay about it."

In both Bastion and Transistor, there is only one major protagonist. If, say, the Kid in Bastion isn’t there, the game really doesn’t have a way to move the story forward. In Pyre, however, members of the huge ensemble cast can come in and out of the story, and in different orders, depending on the player’s actions in the game.

Kasavin explains how he accounted for this problem:� “One of the ways we solve for it is we write for every possible permutation. So in scenes with character dialogue, I have to write how every character would respond to this situation, even though the player will only experience one of those permutations, if any."

"So the player will experience one or zero, and I will have to write many more times that," he adds. "So the outcome is, the player will definitely not see a lot of the content of this game playing it through once, but we're super okay with that because we think the result is an experience that feels much more personal to the player as a result.”

The softer fail mechanic also accommodates Pyre’s organic storytelling. Because you aren’t forced to fight an especially difficult enemy over and over again until you win, the story flows more naturally, and makes for a more personal experience. The developers also sought to make Rites feel somewhat like sports competitions rather than simply all-out war.

“The stuff where there's no Game Over means that you won't get stuck bashing your head against a really difficult boss that you can't possibly get past,” Kasavin says. “So our narrative goals of having hopefully a tightly written, interesting story that feels personal to the player doesn't have to come into conflict with the gameplay goals of these high stakes competitions that you're getting into.”

This is an interesting approach to an age-old problem in video games -- the eternal conflict between essential gameplay and the story the game is trying to tell. It’s Supergiant’s hope that with the Rites so heavily embedded in Pyre’s world, the sports-inspired elements of the game and the lack of a cut and dry fail-state will blend smoothly into the narrative the team is trying to weave.

It also aligns with Pyre’s accessibility. While Amir Rao, the studio’s director, tunes each game the team makes for accessibility, Pyre almost naturally became a game that players of all sorts could enjoy.

“It felt so in theme with the type of story we wanted to tell, and it also opened up so much more possibility in how we could tune it, because players' mileage could vary for sure,” Kasavin remembers. “But it made it possible for us to make a given encounter as difficult we wanted without fear, because even if the player failed, the story would still go on.”

All of these considerations -- the narrative, the competitive mechanics, and accessibility, also ensure that Pyre is closely aligned with Supergiant’s core game design values.

“I think for us, exploring what it means to fail in a video game is really valuable no matter what form the game takes,” Kasavin reflects. “I personally really value when games justify the player's failure loop in the game context -- whether it's part of the story or part of the flow in general.”

Failure in games is often taken for granted -- it’s just part of the experience. But what if developers took the time to ponder this oft-glossed over mechanic?

“Really closely examining that -- how the player gets back into the flow of the experience after having failed is really valuable as part of thinking about a game, thinking about what makes it distinct and interesting, rather than sort of just taking it for granted,” Kasavin says. “I appreciate when games are more introspective about the conventions they use, and we've certainly always tried to do that here despite following many conventions well established by previous games. I think conventions exist for a reason, but should always be examined.”

You May Also Like