Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Erik Svedäng and Niklas Åkerblad talk Else Heartbreak, a story-driven game set in the fictional harbor town of Dorisburg: "a strange kind of homemade Grand Theft Auto, without any guns or cars."

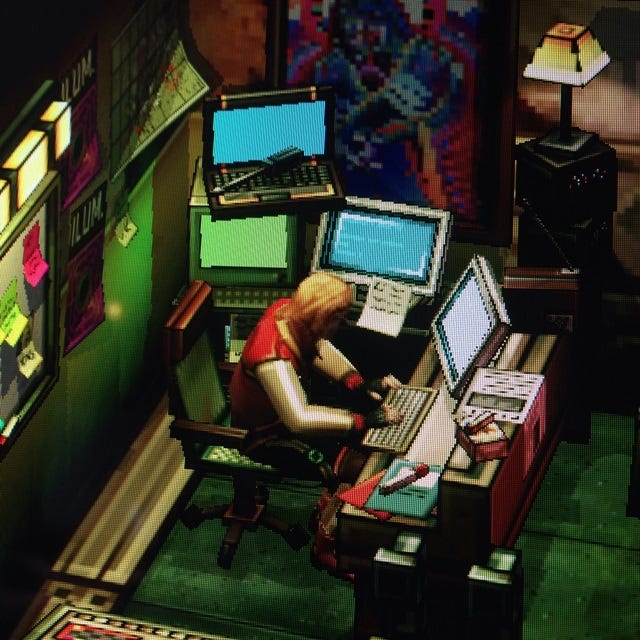

Gothenburg resident Niklas Akerblad says his town's a typical Swedish town: "It has long been home to proletarians, with a strong socialist movement. It is a harbor, but perhaps not a very international one." "It also rains often, and people drink a lot of beer and smoke a lot of cigarettes. There are lots of nooks and crannies everywhere, if you know how to look for them, and also the architecture is mostly old, with a few brutally modern structures built in the middle of everything without any sense of unity. The people are kind but maybe not very open; it takes a while to peel off the layers." I saw a place like that recently, in a sense. Akerblad is the art director on stylishly-titled else { Heart.break() }, whose fictional setting of Dorisburg is based on Gothenburg. The game saw a video demo at the Horizon conference just after this year's E3, and it's been on my mind since then -- simultaneously softly-colorful and faintly grim, but enticing almost in the way only the dense 3D city atmospheres of late-era PSX games can be to me. I've been paging through the visually-intensive development blog, Postcards from Dorisburg, frequently since, longing to visit Dorisburg myself. "We added a lot of rain and loads of scruffy buildings, with a huge amount of pipes everywhere," says Akerblad. "Then there is the presence of modern buildings here and there obstructing the overall picturesque flow of the city. Gothenburg has a large casino, so we felt we needed one as well. Finally, the harbor aspect is very important so we got dockworkers hanging about, and the ocean is an ever-present aspect." Akerblad builds Dorisberg, as well as its animation and concept art, and composes the music for Else Heartbreak; his friend Tobias Sjogren designs all the characters, and Oscar Rydelius is the sound designer. Programmer Johannes Gotlen and animator Ebba Edenstrom have also worked on the project. But its designer, writer and main programmer is Erik Svedang, of games like Slice & Dice, Clairvoyance and Shot Shot Shoot. Svedang's Blueberry Garden won the 2009 Independent Games Festival grand prize. Since its release, Svedang says he's been dreaming of Else Heartbreak in some form or another; his test collaboration with Akerblad would become the iOS game Kometen, and the pair began working on Else Heartbreak after that.

"The original idea came from that I wanted to make a game where the player got access to the code that makes up the game itself," Svedang says. "This evolved into a kind of story-driven adventure about a boy who has to become a hacker to win the heart of a girl he falls in love with. The drama takes place in a city 'where bits have replaced atoms', and politicians and activists fight over the control of the game’s source code." Hacking and coding as a central gameplay conceit seems to be a popular idea right now; it's part of why I'm excited about Else Heartbreak, and part of why I've recently fallen head over heels in love with Blendo Games' Quadrilateral Cowboy. In a 2013 blog post, Svedang wrote of his dismay as he read about Quadrilateral Cowboy's tiny computer-within-a-game, and found it so similar to his own feature idea. But Svedang drew an interesting conclusion from there: Games can no longer thrive on singular "features" alone; no single "gameplay innovation" distinguishes nor defines a work any more. Multiple designers can be expected to step forward to address player demand for "hacking" interactions with games that went beyond matching puzzles and minigames -- "to actually make the machine work 'for real' was a very exciting thought," he wrote. "I hope that in the end people who play games will not be too obsessed with features -- getting hung up on whoever thought of something first, or that something which perhaps seemed like a very novel and weird idea pops up in several people’s work around the same time," he continued in his post. "In the end, each game is its own little world of themes, ideas and things to experience."

"I hope that our approach to interactive story telling will allow players to experience really surprising and interesting things that they will remember for a long time."

Else Heartbreak will be defined by its storytelling -- Svedang tells me that while the team set out to make a puzzle-driven experience, their desire for "telling stories and putting the player in interesting situations" was stronger, and shapes the game. "The gameplay elements like the programming and modification of the game world are very much still there, but their main purpose is to make the world more believable and cool, not only to act as obstacles that need to be passed to make the story progress," he says. "Failure to accomplish something isn’t necessarily bad, and will just create a different kind of story, sometimes an even more engaging one." In Else Heartbreak, the player takes the role of Sebastian, a young man who moves away from home for the first time to take "a crappy job in a city no-one's heard of, a worn-down and rainy place called Dorisburg," Svedang explains. "In the city he gets to know lots of different people and has to grow up quickly to handle the situations he’s put into. Friendship, love, and life-threatening computer programs, to be somewhat more detailed." He describes the game as somewhat like a point-and-click adventure, but in a dynamic world. "There is a richness of simulation that encompasses everything from the characters you meet and interact with to various things like computers, the public transportation system, and the in-game internet. Our goal has been that the world has a strong sense of self-sufficiency to it, and that the player character is not the centre of the universe." "Actually, most things to experience in the game exists mainly because they are beautiful, funny or interesting," he continues. "Else Heartbreak is designed to encourage free-form roleplaying where it should be fun to just go for a walk in the park, smoke a cigarette or visit the casino. So perhaps it could be described as a strange kind of homemade Grand Theft Auto, without any guns or cars."

Akerblad says the main influence for the game's art is a Swedish television puppet show from the 1980s, called Skrot-Nisse. "It’s about a man who lives in a scrapyard and hangs out with a hermit inventor called Bertil Enstoring," he says. "Together they try to escape the clutches of Ture Bjorkman, the mayor of the city, who wants to lay hands on Bertil’s inventions." "The creators of the show built a a very intricate set for the show with loads and loads of details," enthuses Akerblad. "It almost looks like the most ambitious dollhouse you've ever seen, so we wanted to try and capture that. Since the game is in 3D we decided to build everything the way you would build with cardboard boxes and stuff in real life, avoiding advanced shaders and complex geometry, but instead focusing on painting textures like you would with a brush. All in low resolution to still maintain a very graphic feel, not trying to directly copy the real analog thing straight off." Else Heartbreak has been growing slowly and quietly since 2010, and has no set release date yet, though it recently showed at the Nordic Game Indie Night; last year, the Nordic Game Program awarded the team 300, 000 DKK to continue its development. "I’m really excited for the people who will actually take the time to investigate the world that we’ve built," says Svedang. "It has a depth and detail of simulation that I think some people might miss simply because of impatience, or that it’s usually not worth looking for. I also hope that our approach to interactive story telling will allow players to experience really surprising and interesting things that they will remember for a long time."

You May Also Like