Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Jason Johnson looks to the mythological Egyptian god Osiris to draw an inconspicuous parallel between the story of the supernatural being and the practice of collecting objects in video games.

Despite nurturing a myriad of iconic symbols, Egyptian mythology has enjoyed little celebration in the gaming world. Mario stomped on a Sphinx's head or two in the Game Boy's bizarre rendition of the Mario universe, and Lara Croft has excavated Egyptian ruins a few times over. Capcom's overhead shooter Legendary Wings allowed players to transform into a flaming Phoenix, and mummies are an old stand-in in horror-themed game camp. Still, the impact of Egyptian lore on video games seems miniscule whenc ompared to the widespread influences of its Norse and Greek counterparts. But is it?

The dismemberment of Osiris, though not an event from Assassin's Creed's compelling plot line, is nonetheless essential to it. This is due to the influence of an Egyptian myth on the video game medium. This myth has become a gaming archetype, and its implementation can be traced across all genres and generations of interactive entertainment.

The importance of acknowledging this archetype is that it often benefits the design and storytelling of the games it is implemented in. These benefits include a more directed player experience, a better cohesion of gameplay and narrative, and a heightened possibility of establishing a game's own mythology, i.e., a world the player identifies with and cares about.

Video games and collecting things go hand in hand, and the Isis and Osiris archetype is an archetype about collecting. In the myth, Osiris, the supreme, benevolent Egyptian god and also the king of Egypt, is murdered by his brother Set -- who also just happens to the Egyptian god of supreme evil -- and Set usurps the throne.

Dismayed by Osiris's necrophilic ability to produce an heir after his death, Set cuts Osiris's corpse into many pieces and scatters them across Egypt. Isis, Osiris's loving wife (and also a fertility goddess) then begins her quest to retrieve these pieces. Upon her quest's completion, Osiris is resurrected, as he is also a god of resurrection and the afterlife. Osiris returns to aid in vanquishing Set and evil from the kingdom. Echoes of this myth can be heard not just in today's religions, but also in video games, where it could be argued that their influence resounds even more strongly.

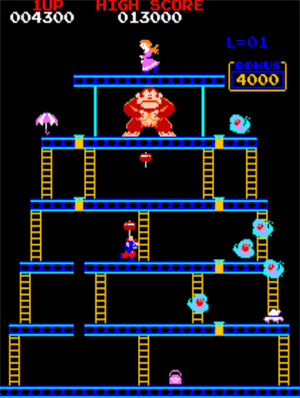

The idea of gathering scattered pieces in order to rectify or avert some malevolence has permeated video game lore. A rudimentary example can be found in the "Rivet" board of Nintendo's arcade classic Donkey Kong. Here, we find Jumpman (or Mario, if you like) playing the archetypal role of Isis as he traverses the board, collecting the eight rivets which connect the girders.

Donkey Kong's "Rivet" board demonstrates a precocious knowledge of the Isis and Osiris archetype.

These rivets are the metaphorical pieces of Osiris's body, and upon their removal, the girders collapse, toppling Donkey Kong, who has taken on the role of Set in the scenario, and restoring tranquility to the construction site. This is comparable to Set's downfall, and the return of the rightful heir to Egypt after the pieces of Osiris's body had been reunited.

The benefits of the incorporated archetype are manifold. One, a more directed player experience is offered. On previous boards, players can choose less risky routes, but the necessity of collecting rivets directs the player through difficult paths while still allowing for freedom in how the player chooses to navigate the board. In this instance, the archetype assists in fundamental game design, enabling a balance to be struck between what a game requires of a player and how a player chooses to accomplish the requirement.

Two, there is a strong sense of cohesion between narrative and gameplay in Donkey Kong. The story is a direct consequence ofthe player's actions. Simply, the player collects the pieces, and Jumpman removes the rivets to defeat Donkey Kong. In broader words, as the player fulfills elements of the archetype, the archetype naturally imparts the narrative of the myth. An archetype can function as the intersection point of story and gameplay, a common ground which both sides are built upon. This concept can be expressed simply in a hypothetical syllogism:

Gameplay = Archetype.

Narrative = Archetype.

Therefore, Gameplay = Narrative.

The benefit of having unified gameplay and narrative is that the player becomes an active participant in the game's world rather than a passive observer of it, which leads to a more satisfactory experience.

Three, there is a heightened possibility of establishing a game's own mythology and creating a world that the player cares about. Archetypes have an underlying connection to the architecture of consciousness, and tend to strike a chord with people on a fundamental level. They convey unspoken and sometimes ineffable ideas. Requiring a player to complete an archetype can help the game connect with the player at the same fundamental level.

This connection gives players satisfaction beyond that of narrative simply overlaying gameplay. Donkey Kong's success ultimately lies not only in its fun gameplay nor in its pioneering narrative, but in how it melds these components into a game that is more than the sum of its parts.

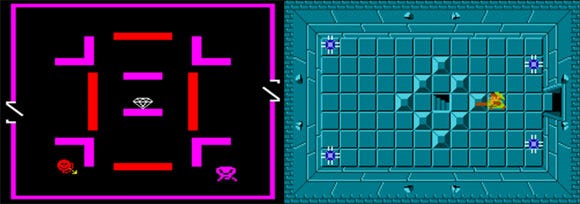

Exidy's Venture, an early dungeon crawler, utilizes a collection aspect similar to that of Donkey Kong's "Rivet" board, and, in the process, evokes the Osiris archetype at the fundamental level of interaction.

The object of the game is to move a character around the board collecting the four treasures, which are guarded by dangerous foes. This very basic invocation of the Osiris archetype -- simply collect the pieces and live to see the next screen -- benefits gameplay by allowing the player freedom of movement in a nonlinear environment, and, at the same time, requiring the player to navigate the more challenging sections of the board.

This is reminiscent of Donkey Kong's collection quest and its resulting directed player experience. Both games serve as examples of the Isis and Osiris myth in microcosm.

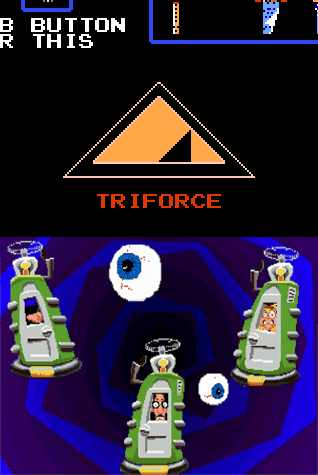

Combining the gameplay of Venture and the narrative of Donkey Kong, The Legend of Zelda incorporates the Osiris archetype into something all together more epic than its inspirations. In Zelda's plot, the hero Link is tasked with reassembling the Triforce, sacred pieces of an artifact, in order to defeat Ganon, rid Hyrule of evil, and rescue Princess Zelda, the rightful heir to the throne.

The most significant aspect of this narrative is that, similar to Donkey Kong, it is relayed almost entirely through gameplay with very little dialog and no cutscenes. The story is easily understood, memorable, even impactful; yet it never detracts from the gameplay. This can be attributed to the archetype, which helps to instill cohesion between gameplay and narrative by having the player enact a direct representation of the story line.

Again, the benefit of cohesive narrative and gameplay is that the player feels directly involved with the progression of the narrative, which serves to pull the player into the game. This illusion of having direct responsibility for the advancement of the narrative is the first step toward immersive gameplay, not hyperrealisitic graphics nor a first person perspective.

Like Venture before it, The Legend of Zelda's gameplay is directed by a collection quest that contains remnants of an Egyptian Myth.

Again, the archetype's role in accomplishing cohesion between gameplay and narrative is that it provides a template for coupling them.

A decade after Donkey Kong, video games had matured to the point where narrative and gameplay could stand on equal footing. Released in 1993, Square's Secret of Mana is a good landmark for the increasing emphasis on narratives in games. Secret of Mana combines action-adventure elements from Zelda and RPG elements from Square's own Final Fantasy series, and, in the process, fuses the Osiris archetype with their narrative style.

While it's true that Square games predating Mana bear resemblance to the myth -- early Final Fantasy plots often revolve around gathering crystals to ensure victory of light over dark -- Zelda's inspiration on Mana brings a fuller realization of the archetype to the game.

To begin with, both games involve a legendary sword: Zelda's Master Sword and the Mana Sword. While Link must collect eight Triforce shards, Mana's Hero must seal the eight Mana Seeds to restore power to the Mana Sword. Here, the Mana Seeds are analogous to the severed pieces of Osiris's body, and the restored Mana Sword is symbolic of the resurrected Osiris.

Likewise, Mana's antagonist Thanatos, whose "life force is growing darker, [who] feeds on hatred and destruction," is the stereotypical Set. Just as Ganon uses the power of the opposing Triforce to rule Hyrule, Thanatos uses the power of Mana, the source of all life, to destroy the Mana Tree, the protector of life, and to rule the world. This establishes a theme of good being used against itself to commit evil, which is analogous to Set using the armed forces of Egypt to combat Osiris's army in the battles that followed Osiris's resurrection.

These situations imply some complex ideas regarding the duality of good and evil. Namely, that good and evil are two sides of the same coin; they originate from the same place. Both Osiris and Set were born of Nu and Nut, the Egyptian manifestations of the ocean and the heavens. Likewise, the similarities in appearance of the Triforce of Wisdom and the Triforce of Power suggest a similar origin. Similarly, the Mana Tree and Mana Fortress are both comprised of Mana.

These ideas will likely go unconsidered in a playthrough of the game, but nevertheless penetrate the player's subconscious and assists in establishing a game world that the player is genuinely curious of and cares about. An asset of narratives based on mythological archetypes is that they impart subtle complexity beneath the surface of a game, so that the story seems neither dogmatic nor fluffy.

Together with RPGs, adventure games paved the way for the blossoming of game narratives. It just so happens that one of the adventure genre's crowning achievements is cast from the Osirian mold. LucasArts' Maniac Mansion: Day of the Tentacle contains all of the respective elements of the archetype, while putting its own unique spin on it.

DOTT's variation is that, instead of one hero collecting the pieces, three heroes do. Hoagie, Bernard, and Laverne, the threep layable characters, each take on the role of Isis. They are stuck in three separate time periods, and must repair their time machines in order to reunite.

Here, time itself plays the Osiris role, as the past, present, and future must be reassembled into one stream. The efarious Purple Tentacle functions as Osiris's nemesis Set. Interestingly, when Hoagie, Bernard, and Laverne reunite in the same time, they are actually physically united, as Purple Tentacle zaps them with a ray gun, combining the three into a single body. This is excellent symbolization of Osiris's reunified body.

Also worth mentioning is the variation on the theme of good being used against itself to commit evil. In DOTT, mad science is used against itself to commit good, to comic effect.

DOTT is a game of interconnected parts, as the past, present, and future settings exist concurrently. Considering that the past, present, and future are identifiable with the severed and scattered pieces of Osiris's body, one can see how the structure of DOTT is presented in the Osiris archetype's format.

The Osiris myth can act not only as a gameplay objective and narrative guide, but also as the framework for an entire game. In comparing DOTT to its older sibling Maniac Mansion, a great game in its own right, some structural benefits can be observed.

MM and DOTT exhibit the same basic gameplay, but while DOTT is divided into four distinct parts, MM has only one, wide open, sprawling gameworld. The end result is that DOTT is much more user-friendly, because it offers a more directed player experience. Wandering around aimlessly is not much fun thing, and it happens far less frequently in DOTT.

Another advantage of the Osiris archetype's structure is it gives the player a greater sense of progression. In DOTT, each reenergized time machine indicates a cleared section and serves as an incremental reward for the player throughout the course of the game.

These checkpoints can make lengthy games less daunting and give players motivation to keep playing. These pieces can also mark a player's progression in a game. For example, a diagram of collected Triforce pieces on The Legend of Zelda's item selection screen displays how close the player is to the endgame.

The pieces of Osiris can serve as milestones in the progression of a game, indicating how near or far the player is to the ending.

A phenomenon inherent in archetypes is that the further they are disseminated, the more

they change in the process. Storytellers add and subtract elements to better suit their audience. Details are misconstrued. Parts are forgotten. These changes occur again and again as the story is passed on, and eventually the archetype evolves into something else.

This occurrence is no different for gaming, and the Osiris archetype's course of evolution can already begin to be seen in the previous examples. Mana's Hero slays a dragon after Set has fallen. DOTT has three Isis types. Still, these variations on the archetype are followed by more profound departures.

One common variant on the Osiris myth in gaming is the theft type. Theft types involve the typical collection quest, but near the end of the quest, the Set figure emerges to steal the pieces from the Isis figure, usually in pursuit of power or to bring about world destruction.

Sega's Skies of Arcadia is an apt example. In Skies, the adventurers are tasked with assembling six Moon Crystals, but before their quest is complete, Ramirez appears and steals the crystals, leading to a battle in which the fate of the world is determined.

Some Tomb Raider games also adhere to this variation. In Tomb Raider 3, for example, Lara discovers four mystical artifacts only to have them stolen by Dr. Willard, who intends to use their power to mutate the human race into monsters.

Such variations diverge from the archetype at the point where an evil force manipulates a good entity to oppose a good force, i.e. where Set uses the Egyptian army against Osiris's army. These variations were likely first enlisted to preserve the theme of heroes fighting against benevolent forces that have fallen under the influence of evil.

It's possible that some game narrative lacked the necessary elements to follow the archetype verbatim, yet its creators still wanted to include the epic ending, so they came up with the work around of having the villain steal the collected pieces in order to let the traditional ending remain.

In these situations, the hero must overcome the villain who has gained the power of the benevolent pieces. Lara battles a venomous Dr. Willard who has used the power of the artifacts to transform into a hideous spider. Vyse and company confront Ramirez, who uses the crystals to summon and merge with the doomsday device Zelos. Improvisations like these are how variations on myths are born.

Another common variation on the Osiris archetype is the twin mission kind. This variant places both the hero and villain on conflicting quests, which typically cross one another at the culmination of the narrative.

Square's Kingdom Hearts is the quintessential example of the twin mission type. Building on the traditions of Secret of Mana, Kingdom Hearts places a lad named Sora in Isis's shoes as he sets out to seal the scattered Keyholes and thereby prevent darkness from entering their worlds. Meanwhile, Ansem, the game's Set type, is on a collection quest of his own, kidnapping the seven Princesses of Heart in order to use the collective power of their Hearts to open the door to Kingdom Hearts, which will unleash darkness unto all worlds.

This is interesting not only due to the emergence of the Osirian theme in which forces of good are used for evil, but also because the villain's collection quest more closely resembles the collection of Osiris's body than the hero's does. The Princesses of Heart are required to congregate in order to resurrect the power that unlocks the door to Kingdom Hearts, just as the pieces of Osiris's body must be recombined in order for him to beresurrected.

Sora's quest is more structural. He simply seals each Keyhole, leading him to his confrontation with Ansem when their quests cross at the climax of the game. Ansem successfully unites the Princesses of Heart so that he may open the door to Kingdom Hearts. At the same time, Sora must seal the final Keyhole, locking the door to Kingdom Hearts, in order to prevent darkness from consuming the world. These two paths set the hero and villain on a collision course and result in the final struggle of good and evil.

Ubisoft's Assassin's Creed follows a similar twin mission structure. Assassin's Creed's narrative features parallel plotlines, and contrary collection quests can be found within them. One of the twin quests takes place in the Holy Land during the Third Crusade, where the assassin Altaïr is tasked with enacting nine assassinations in order to regain standing in his clan.

Each assassination lends him insight into the true nature of his mission, and at last he learns that he has been deceived by his leader Al Mualim into carrying out a nefarious agenda. Altaïr then returns to confront Al Mualim.

In this plot line, Altaïr serves as Isis, collecting the pieces of Osiris -- the insights into the intrigues of the Crusade, which he learns of by enacting each assassination. Al Mualim plays a near flawless role as Set, sending Altaïr about his quest in a scheme for power.

A concurrent quest unfolds in the laboratories of Abstergo Industries, a modern incarnation of a secret society seeking to shroud humanity in illusion. The organization has imprisoned Desmond Miles so that scientists can scan Desmond's mind for memories of his ancestor Altaïr.

In specific, the scientists seek a memory involving a Piece of Eden, an artifact Altaïr took from Al Mualim after he killed him. This artifact contains the power to create illusion, and Abstergo intends to use it to create the illusion of peace -- therefore putting an end to world conflict. This dual plotline presents the scientists of Abstergo as Isis, collecting pieces of Desmond's hereditary memories, which are the scattered pieces of Osiris, in order to put an end to world conflict -- which can be personified as Set.

These parallel plot lines overlap at the Piece of Eden. Altaïr defeats Al Mualim, preventing him from using the Piece of Eden to cast an illusion of peace upon the world. In the future, the scientists of Abstergo use this very memory to help locate a Piece of Eden in hopes of casting that illusion of peace upon the world.

But the comparisons between Assassin's Creed and the Osiris archetype don't end there. Assassin's Creed possesses yet another overarching plot line which links it to its upcoming sequels and, at the same time, links it to the relics of mythology. See, the Piece of Eden is but one piece of many, and, hypothetically, Abstergo will discover a new piece in each consecutive sequel, effecting a collection quest across multiple games.

Just as Assassin's Creed's sequels will continue to replicate the Isis and Osiris archetype, entirely new entries in interactive entertainment will as well. Though the archetype will continue to be divided and mutate along the way, its core principles will remain, connecting whatever games experiences that exist in the future to the gameplay and narratives of games from the past.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like