Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

"The death of the author." It's a concept used in literary criticism, and it means that whatever the author intended to say when he or she wrote the work, it doesn't matter to the reader. But how could this apply to game storytelling?

Previously published on my personal blog.

For many years, there has been this long-standing debate among game studies academics called “ludology versus narratology.” Basically, it’s an argument between people who see gameplay as the most important part of a game (ludologists), and those who think that games should be treated as a new form of narrative (narratologists). Personally, I would call myself a narratologist, but I think it’s best to keep both viewpoints - the unique nature of games gives them many different ways they can present stories, characters, and narrative within gameplay.

Obviously, some games are made to tell a story and the gameplay elements are designed around it, such as Telltale’s The Walking Dead adventure game (which I love dearly and will talk about another time, I promise). But most games, it seems, don’t bother with a story (or much of one) at all and no one begrudges them for it. Even so, some really well designed games will give the player the tools to create their own narrative, one that could be better than the one the game gave the player in the first place.

That sounds stupid, right? How can a player’s own personal roleplaying in a game like Minecraft or Animal Crossing or Super Smash Bros. Melée be better than narratives crafted by professionals? Well, the obvious reason is that right now, most game stories are about on the level of your average children’s cereal commercial. But more importantly, if a game puts a huge amount of effort into creating a unique world to explore, it really doesn’t need to do anything else to get the player’s creative juices flowing. Even if the result is against the original intent of the developer.

Take Animal Crossing: Wild World, for example. Pretty straightforward, right? You’re a dopey kid who lives in a small village filled with talking animal people whose sole motivation for getting up in the morning seems to be to pelt you with more and more obnoxious fetch quests. Not a lot more to it than that. But somebody on SomethingAwful noticed that the town seemed awfully secluded and the animals’ behavior was a little bit creepy. This wasn’t the designer’s intent, but the environment that they created was so idyllic and richly detailed that author Chewbot took that setting and turned it into one of the most famous Let’s Plays ever.

On a similar note, Super Smash Bros. Melée was a game that my brother and I played almost constantly between 2001 and 2008. Yes, it had a story of sorts, but the fact that so many disparate characters were together in these richly detailed environments led to so many possibilities for storytelling. My brother and I would play a game we called “The Adventures of Kirby and Kirsy” where he would play as the pink Kirby and I would be the yellow Kirby (who we decided was Kirby’s sister, Kirsy). We would always start out at the Fountain of Dreams stage and decide what adventure we were going to have, voicing our characters and the rivals they would come across. We turned the “evil” Metal Mario back to the side of good, rescued our brainwashed friends who attacked us, fought the robotic wireframe army, and came home to rest at the fountain again. In game, this was just a series of multiplayer battles we set up, but to us it was a far more engaging story than the standard fighting game set-up the game handed to us.

That might sound like nothing more than kids making stuff up while they played a video game, but keep in mind that the popular webcomics Awkward Zombie and Brawl in the Family are, or started out as, emergent narratives of the Super Smash Bros. series.

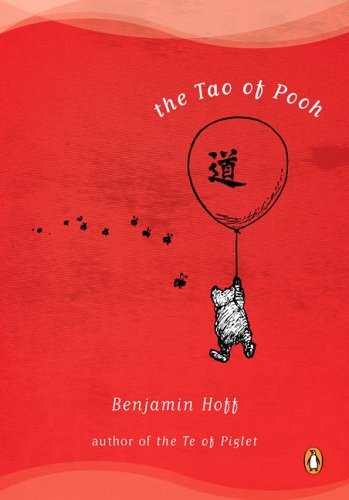

There’s this concept in literature studies called “the death of the author,” which means that whatever the author intended to say in the work has no bearing on what the reader can actually take away from the experience. For example, there are all kinds of books and articles that interpret Winnie the Pooh as an exploration of Tao philosophy, a representation of a child’s grief, or a positive portrayal of characters with mental disorders. Whether A. A. Milne ever intended any of that to come across while he was writing doesn’t matter from the perspective of “the death of the author.” What matters is that the work sparked discussion and can be used as a tool to explore different points of view.

I think that that’s true of video games, too. I like to call it “the death of the designer.” Whatever the designers of a game intended, the player can create whatever they want from what they’re given. And what they create can actually be better than the story the game already may have had.

This is kind of where narratology gets a bit of a bad rap, though. I don’t think that every game has a story – I think that every game can have a story. But one of the most prominent narratologists, Janet Murray, seems to have the opposite viewpoint. She says that Tetris is “a perfect enactment of the over tasked lives of Americans in the 1990s - of the constant bombardment of tasks that demand our attention and that we must somehow fit into our overcrowded schedules and clear off our desks in order to make room for the next onslaught” in her 1997 book Hamlet on the Holodeck.

Well, it’s a Russian game and it was made in 1984, so we can safely assume that the designers didn’t intend that unless they could see into the future. So no, that isn’t the story of Tetris like Murray says it is. What it is, however, is her own emergent narrative from playing Tetris. And with the “death of the designer” concept in tow, we can call her interpretation just as valid as anyone else’s, including whatever the designers wanted to say (if anything) when they created the game. So she’s right, but not in the way she thinks she is. …Wait, what?

Sorry that this article wasn’t that funny. I wanted to clarify what I believe to be one of the primary sources of engagement that video games can offer. Even if the player doesn’t have such a fully formed narrative in their head while they’re playing a game, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t investing themselves into it. Every person is going to have a different reaction to a game, and because of the rich and expansive worlds that some games create, we’ve gotten such great works as “The Terrible Secret of Animal Crossing” and even “Twitch Plays Pokémon.”

So what do you think? What emergent narrative experiences have you had with your favorite games? Do you think I’m completely wrong? Just let me know, and I’ll see you next time.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like