Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What sort of characters work best in video games? Iron Lore writer and designer Ben Schneider (Titan Quest) references Psychonauts, Greek mythology and Planescape: Torment in order to give insight into making playable characters that are “vibrant, real, and memorable.”

I’ve always enjoyed holding forth about how many limitations there are for stories in video games. Often to an audience of non-gamer friends, I’ll start by pointing out what you can’t do in a game with regards to the story. Most of it has to do with the protagonist. Because the hero is the player character, you can’t make that hero anything the player might balk at playing. For this reason, many of the most awesome main characters from film, fiction, and television don’t really work so well as a main game character.

For example, take Oedipus or Clytemnestra: the emotions that might make you gouge your own eyes out or stab your husband to death are one thing to witness, and another to do, even fictionally, even by proxy. Even Achilles doesn’t really fit the bill. There’s nothing wrong with being the world’s greatest warrior, but sitting and sulking in your tent – over some slave girl? Let’s say you begin the plot immediately after all the pouting – it’s still going to sit wrong. “Wait, why was I mad? Why was I being such an idiot? And now I’m suddenly supposed to be all mad about this friend who went and got himself killed?”

There’s no need to resort to antiquity, either. Add to the list Thelma and Louise, Travis Bickle, Holden Caulfield, Amelie, even good old Hamlet. What makes every one of these characters memorable depends on a key moment or characteristic that the player would resist and resent as an imposition on his free will.

And this is the root of the problem: the player wants a character to play, choose, act, and feel with. Being told how they should do those things is somehow, mysteriously, a violation of the contract. Perhaps it is interfering with a basic principle of agency. Maybe it’s the same principle that makes most of us hopelessly awkward and uncomfortable when we try to act.

The feelings and impressions that we create for the player must be earned by providing them with playable experiences, not by telling them who they are. Would you, in a game, opt to feign madness in order to get revenge, or construct an elaborate Easter egg hunt for the man you have a crush on, or make your grand finale at 70mph off the edge of a cliff?

The feelings and impressions that we create for the player must be earned by providing them with playable experiences, not by telling them who they are. Would you, in a game, opt to feign madness in order to get revenge, or construct an elaborate Easter egg hunt for the man you have a crush on, or make your grand finale at 70mph off the edge of a cliff?

Wouldn’t it bother you to think of the other choices you could have made? There is a steeper price of admission for choices that the player considers their own. Like the men and women of Greek legend, we gamers never want to be told our destinies. We insist on being our own masters – or at least the buzzed impression that we are.

As a result, if the player is going to accept the player character and invest in the game on more than a mechanical level, the limitations for what that character can be are real and formidable.

Many of the tools and examples that it’s tempting to steal from passive story-telling just won’t work. The hero cannot be so very stupid, daft, or brilliant that we can’t find ourselves in them. They can’t be so heartless or make such bad decisions that we push the mouse or controller away from us and wrinkle our noses. They cannot keep too many secrets or flip out at just anything, or miss obvious clues; there is a pretty small limit to the size and number of inner demons you can infest the hero with … at least in our current age of game storytelling.

If we want to create truly outstanding player characters, these constraints present us with some hard, specific questions. What sort of characters do work in video games? How do we create them, present them, and make them vibrant, real, and memorable?

There are two heroes in the Odyssey: Odysseus, the namesake, and Telemachus, his son. Now these are two gents who could step straight into a video game. After all, the Odyssey may well have been the original adventure story. Corresponding to the legendary, ingenious father and the good and loyal son, we can describe two general types of player character that are workable: the action hero and the everyman. These two tropes are rightly the staples of video game heroism.

The everyman is Dorothy of Oz and Frodo of Middle Earth. He or she is essentially the closest thing to who we ourselves are, thrown into the extraordinary circumstances of a ripping good tale. True, we often find the seeds of greatness in these characters, but, like Harry Potter and Luke Skywalker, they have humble beginnings.

Everyman characters are always a person stripped down to just their most sympathetic qualities. They are good, but not too good, and humbly average, at least at first and in outward appearance. Their most important feature is a highly polished surface, in which we can see our own faint reflections at all times. The everyman is never very proactive, at least to begin with. As with Dorothy, Frodo, Harry, and Luke, the action must come to them.

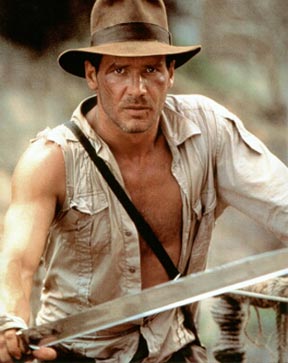

The action hero, on the other hand, is more about who we wish we could be. This type has never seen much point in depth or nuance. A look, a particular swagger, phrase, or other gesture is all it takes to get you Indiana Jones, the dusty cowboy, Batman, or the essential sardonic, hard-drinking ex-Green Beret. After all, there’s no need to clutter your fantasies with details. Unlike everyman characters, action heroes can jump into the action. They can jump onto your screen, fist flying, doing what they do best.

The action hero, on the other hand, is more about who we wish we could be. This type has never seen much point in depth or nuance. A look, a particular swagger, phrase, or other gesture is all it takes to get you Indiana Jones, the dusty cowboy, Batman, or the essential sardonic, hard-drinking ex-Green Beret. After all, there’s no need to clutter your fantasies with details. Unlike everyman characters, action heroes can jump into the action. They can jump onto your screen, fist flying, doing what they do best.

Note that the action hero and the everyman are really just flip sides of the same coin. The one is action, the other responds to it. The one arrives on the scene ready to do business, while the other must slowly learn and accept their fate and responsibility in the tale. In other words, both of them are ways of letting the story take precedence. They are both children of the plot.

James Bond and Feivel are twins, separated at birth. In video games, this form-follows-function character trait is even more important, where the protagonist steps aside not just for a good action-packed story, but for the many mechanics and systems of the game itself, which must always reign supreme.

Working from the template of the everyman and the action hero can help you achieve buy-in from the player, but it’ll take more than that to make your player character something special. In fact, making your protagonist safe is really directly at odds with making him or her original, evocative, or lifelike. There is a vital arm-wrestling match that goes on here between all those limitations and the creative goal of making a really good, memorable character. It may be that successfully walking that line is what gives the best game characters (and all formal creative endeavors) that elusive magic and vibrancy.

Be that as it may, we’re not done listing all the various constraints and limitations. The problem of finding an acceptable player character is followed directly by the problem of how to present that character to the player. The player only knows their avatar as presented, after all. And it’s an important distinction.

To give the cast of Psychonauts the level depth and individuality he wanted, Tim Schafer created mock-Friendster pages for each character. But this is not how we come to know the hero Razputin. Instead, we meet the be-goggled hero of the game when he crashes the opening ceremonies at a summer camp for psychically gifted children – and manages not to get kicked out. His charming bravado and sincerity come through in spades in the several minutes of the intro scene, without almost any of the personalities, relationships, and background information that Mr. Schafer so diligently prepared.

For Psychonauts, Doublefine created a charming and very well developed protagonist. This is by no means the industry standard, and, in fact, I’m not sure you could say that as an industry, we have all agreed that such definition is the goal. Most game developers do a pretty good job of finding that action hero/everyman sweet-spot, but far fewer take the time to make more out of the hero or find a compelling, striking way to introduce them.

For Psychonauts, Doublefine created a charming and very well developed protagonist. This is by no means the industry standard, and, in fact, I’m not sure you could say that as an industry, we have all agreed that such definition is the goal. Most game developers do a pretty good job of finding that action hero/everyman sweet-spot, but far fewer take the time to make more out of the hero or find a compelling, striking way to introduce them.

God of War, Max Payne, and Grand Theft Auto 3 (and 4, it appears!) stand out in this regard, simply for properly setting up the beginning of the game, even, in Max Payne’s and GTA’s cases, if the setup is a pastiche of pulp fiction clichés.

Other games approach the issue by defining the hero as little as humanly possible. Half Life 2 is an example of this category. Although you technically play as Gordon Freeman, it feels much more like you yourself have been sucked into Valve's beautiful, dynamic, lovingly crafted world. But in the end this hurts the story side a little – Alex’s role as a potential love-interest feels more like the developer flirting with its fan-base than a romantic sub-plot.

More peculiar, and, to my mind, problematic, is when a game hands the job of character creation over to the player. This is the standard in Western-style RPG's, inherited more or less wholesale from their pen-and-paper counterparts. But there is a big difference between Dungeons & Dragons and, er, Dungeons and Dragons Online. The table-top gamers ostensibly role-play – as in act – and player-crafted characters are a real element of that. We have not yet invented social AI that allows for the same sort of acting in computer RPG's.

Herein lies a notion I would love to try and dispel, that being that ninety-nine out of a hundred gamers will, under no circumstances, make up elaborate back-stories for their characters. They will not imagine a rich Tolkienian narrative on top of the game’s bare plot. They will do nothing at all like use the game’s narrative structure as a canvas on which to construct their own self-expressed meta-narratives. Story and character-development are our jobs. The gamer is not an aspiring actor or writer; he or she just wants to be entertained. More specifically, the gamer would be happiest to be able to step right up to the role of the dashing hero, with a full tank of gas, ready for the road.

The real reason that common Western RPG conventions such as character customization and multiple quest/career paths have persisted is that they make good gameplay. Customizing the appearance, alignment, and profession of a character belong to sandbox and sim styles of gameplay, not to game storytelling.

Having to deal with so many different configurations of player character makes storytelling harder, if anything. The color of your hair and whether you are a wizard or a warrior are not dramatically meaningful choices. And while choosing to between good and evil actions can be, if a bit crude, many games (such as Fable) manage to make it a purely customization-based affair. Now it is true that these customized characters fit the everyman bill, but they don’t accomplish much more than that. The player is bringing their own hero to the story, and the fit, not being tailored, is a poor one.

There is, in fact, an inherent credibility problem with introducing the player to their avatar. Imagine asking someone to play Neo in the beginning of the original Matrix movie. Unless we whisk you from scene to scene, you need to know how to get around your house, find your way to work, and act like you are doing your job.

Plenty of older games might have just left you to wander the city and get hopelessly lost – but at that point, you’re not playing as Neo, are you? And then when the action starts, you don’t have the layout of your office memorized, and you feel like you’re bumbling when you should be all reflex and adrenaline. Plunking the player into an unfamiliar character in an unfamiliar world is a double whammy. It’s hard to believe that you are really the character when you don’t know a damned thing. And how are you supposed to know a damned thing three minutes into the game? Ten page or twenty-minute introductions are, of course, out of the question.

One way to handle the problem is by getting out of one or both responsibilities. Once again, Western RPG’s have proven themselves kings of the weird compromise by coming up with any number of scenarios where you are truly a stranger in a strange land. In the Ultima series you are summoned out of this world as the Avatar of Virtue. The Elder Scrolls games always make you an unknown prisoner, who is somehow released into an unfamiliar land, and Knights of the Old Republic uses a similar device.

To be fair, as a genre RPG’s push the envelope in terms of letting the player interact with the story. If they fail often, it’s because they tried. All the same, the stranger in a strange land trick is not subtle and it’s already become a bad cliché. True, adventuring in exotic locales is a tried and true aspect of all storytelling, but it loses much of its punch if there is no home to provide contrast, and to fill in the Campbellian cycle.

And yet one of my all-time favorite games is the RPG Fallout, which spins its own version of an unknown hero in unfamiliar territory. There are some key differences, however. First, there is a sense of a safe home, and second, in a sense, you know exactly who you are. Home is an underground bunker, which has been sealed away from the world ever since the nuclear holocaust. But the bunker’s water-purification chip has failed, and somebody will have to venture outside and find a replacement. And that someone is you.

The feeling of wide-eyed naiveté as you step into the hot sunlight of the radioactively transformed surface-world feels natural and earned. The game simply and gracefully has given you an everyman character to play, and a plot with the urgency and drama to make it work. You are a messenger on whom lives depend, and, as you learn more about the looming threats lurking in the wasted world above, a potential savior. (The point belongs to some other article, but the familiar Mad Max setting makes your immersion into the world that much easier.)

In other words, Fallout doesn’t avoid back-story and character definition at all. Instead, the player character is properly defined by the circumstances of the story, a perfect everyman. Situation is everything, and Fallout isn’t just a good beginning. By largely eschewing simplified morality (you don’t have to be a good guy, and most of the people in the game aren’t stamp-mold bad guys), these interactions become more real and meaningful than in almost any other game I’ve played.

A more direct approach to starting the hero on familiar ground can be found in the new Zelda game, Twilight Princess. The game does an elegant job of placing you in a small village where everyone knows you. True, you have the freedom of an independent young man, but they still manage to conjure a mentor, a love-interest, a trusty steed and a number of other personalities in early stages of the game.

What are some of the tools Twilight Princess and other games have used to successfully introduce a character on familiar grounds? At least half the answer lies in successfully using UI to simulate knowledge. If maps are filled in as you explore, familiar areas should contain revealed and annotated maps. Both Twilight Princess and Indigo Prophecy do an excellent job of using early gameplay tasks to familiarize yourself with areas so that you can perform with more confidence later on.

What are some of the tools Twilight Princess and other games have used to successfully introduce a character on familiar grounds? At least half the answer lies in successfully using UI to simulate knowledge. If maps are filled in as you explore, familiar areas should contain revealed and annotated maps. Both Twilight Princess and Indigo Prophecy do an excellent job of using early gameplay tasks to familiarize yourself with areas so that you can perform with more confidence later on.

Both of these games also do a great job of using dialog with people you know to create, inform, and reinforce the information you need to feel like you know where you are. I am also of the opinion that internal monologue has great, if largely unused potential in this department, among others. By experimenting with techniques like these, we will, over the course of time, begin to assemble a vocabulary, in the semiotic sense used in film theory.

For instance, showing the hero’s home in the intro cinematic, or flashbacks and extra camera angles like those in Indigo Prophecy could slowly become familiar tricks of the trade. As the state of our art evolves, we should be able to put our audience in the shoes of more interesting, more original, and more powerful protagonists.

There is one technique for helping the player step into the role of the game’s hero that deserves special attention: giving the hero a real role in the story. Planescape: Torment famously places you in the role of an immortal amnesiac, who starts the game waking up on a mortuary slab with a splitting headache, no memory, and a note to himself gouged into the skin of his back. (You didn’t really think it was possible to write about story in games and not mention Torment, did you?)

A bold move, and one of the best stranger-in-a-strange-land introductions ever. All the same, this clever trick would ultimately have been a clever trick, and no more, if it had not also been a beautifully evocative prelude to the sophisticated and poetical central theme of the game.

The game whirls around the questions of your past and your nature, and then the nature of these very concepts. These aren’t just problems that the designer had to deal with – they are problems that you, as the Nameless One, grapple with, and which change you as you unravel the mysteries of your own past. I believe the fact that the hero of Torment grows and changes through his choices and experiences over the course of the story is one of the reasons many of us have found this game so powerful. We have changed and grown through the playing of it.

In a sense, it seems surprising how rarely you see heroes change and grow in games. It is, after all, such an important component to other forms of storytelling (not to mention the point of Joseph Campbell’s mythical journey, which he claimed was a representation of our inner lives). But a glance back over all the constraints placed on the player character make it pretty clear how hard it is to get to the point where you are even considering something so advanced.

And yet, as with Planescape: Torment, I think that the potential to give the player an experience of dramatically significant choices, leading to real and powerful character growth, might more or less be the holy grail of story-telling in games. From the whole-game view, in other words, this is what a really great player character can give you: the type of emotional investment in the game that takes it from fun to memorable, meaningful, and timeless.

When it comes to how to give the protagonist a character arc, Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey cycle is an excellent place to start. This cycle lays out the mechanics of the structure of, supposedly, all myths, and is described in detail in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Both everyman and action hero plug perfectly into the arduous journey from home into the Unknown, where (and this is the point here) he or she learns or grows in some vital and meaningful way, then struggles to return with that accomplishment to the home world once again, completing the cycle.

For the everyman, growth generally means rising to the challenge of becoming great. While in video games this will most often mean becoming the most powerful warrior in the ‘verse, it does not have to be that literal. Indeed, you can remain a simple hobbit and still rise to the duty and challenge of your destiny.

The important thing is that where you were just another person when the tale began, because of luck or fate or hidden virtues, you must come to accept and master a greater role. This involves sacrifice and difficult choices. The Buffy the Vampire Slayer series largely focused on this one aspect of hero growth, moving through it slowly and developing all the themes to be found in struggling to accept greatness and relinquish normalness.

Of course the action hero already knows he’s hot stuff. He can’t grow or change by doing what they do best. Instead, the action hero has two major paths for development. As with everything in the shades-of-gray land of story mechanics, these are actually the same thing.

One path of growth happens when the action hero encounters a problem that his powers don’t address. This is the classic “if all you have is a hammer, all your problems look like nails” scenario, where you come to something that hammers just don’t work on. One day the action hero meets the femme fatale or the villain who uses brains rather than brawn, and then must face his own shortcomings, struggle, adapt, and overcome them.

The other sort of development is when the hero meets a challenge that far exceeds her powers. Here a good setback is required to cut the hero down and give her a good sense of doubt to struggle with. After the doubt and the struggle and perhaps a glimpse at what the world will look like if she abandons her duty when she is needed most, then will return to the treadmill, train, get a good montage scene in, and push herself to be a worthy opponent of her foes.

Mysteries are good tools both for intriguing the player and matching character growth with plot development. For a good mystery to be more than a trick, it has to be personal: the truth about the death of your father, about the girl or boy that you love, about who you yourself are.

Mysteries are good tools both for intriguing the player and matching character growth with plot development. For a good mystery to be more than a trick, it has to be personal: the truth about the death of your father, about the girl or boy that you love, about who you yourself are.

As good as mysteries are, difficult choices are better. Case in point is the Train Job episode of Firefly: more than halfway into a problematic job for a shady employer, the crew realize that their actions are doing great harm (the stolen goods are needed medicine). The episode does a great job of conveying the difficulty in choosing to do the right thing. Difficult choices do not have to mean forking (or rubber-banding!) story paths. A choice with one option – could they not return the medicine? – as long as it is truly, morally difficult and not just a styrofoam zen koan, is still a choice. Perhaps one-option choices are even better for video games, as they do not interfere with the player’s desire to succeed at the game.

Sometimes when I talk about what’s possible for stories in games, my non-gamer friends ask me if games can ever be as good as books and movies. My answer is always that as limited as game stories seem to be (until someone proves us all wrong!), they have the potential to be the most powerful thing you could experience – because as the player, you are the main character. Every heartbreak and every revelation is that much closer to your jugular vein.

For what it’s worth, games are better when their heroes are good, strong characters who will grow and challenge the player during the time they spend together. While the protagonist is by no means the one make-or-break keystone of a game, it is the portal into the game for the player’s imagination – the term “avatar” is used for a reason. If the hero is bad enough, they could make an otherwise great experience hollow, and if the hero is awesome enough, doubt ye not its power to bring the game to life.

By and large, successful player characters will be either action heroes or everymans. That is, they will either be striking symbols of adventure wish fulfillment, or they will be sympathetic placeholders that let a firecracker plot do its work. Perusal of Hollywood blockbusters and adventure classics will reveal that these roles have their own grand traditions beyond the realm of games, and are in no sense limited, dramatically.

Dramatists should take heart for another reason: all of those limitations and constraints apply to the player character only. As we build better ways to interact with NPC’s, we can have our share of Iagos, Gollumses, and Kaizer Sözes. And like Shakespeare’s Iago or Brad Pit in Fight Club, I don’t know that it would be a bad thing for a truly outstanding NPC to steal the show.

Dramatists should take heart for another reason: all of those limitations and constraints apply to the player character only. As we build better ways to interact with NPC’s, we can have our share of Iagos, Gollumses, and Kaizer Sözes. And like Shakespeare’s Iago or Brad Pit in Fight Club, I don’t know that it would be a bad thing for a truly outstanding NPC to steal the show.

As we pioneer new ways to introduce and portray protagonists in video games, I hope that we begin to shuck off some of the awkward glitches of the first several nascent decades of game design. I believe we are already seeing the first signs of a new generation of game heroes – and they are, thank goodness, as unlike each other as Alan Wake, Razputin, Kratos, and whoever that woman is in Hard Rain.

These and all the other games yet to be made, all the manifestations of the everyman and the action hero, like so many multi-colored and luminous skins for the players to put over their own, and feel the thrill of the game tingle on the tips of their fingers and up their spines.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like