Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Open worlds and sandboxes are big, scary places for narrative designers. Whatever your mechanics may be, and however your tale is told, adhering to these four basic but essential mantras will help players better engage with and understand your story.

This blog post is adapted from a talk delivered during Playcrafting's Avalanche Month in July 2017. The original talk was disorganized and rambly; I hope this more polished version is useful to you!

At Avalanche Studio's NYC office. Photo credit Victoria Setian. Thanks to Dan Butchko and Playcrafting for the opportunity to chat with the NYC Gamedev community!

Anyone who’s taken a stab at it knows that storytelling in an Open World game can get complicated. We create crazy, systems-heavy sandboxes with the intent that anything can happen, then invite players to break sequence or step out of line or just ignore us completely.

The vastness of the player’s possibility space is daunting, so we find ways to make our stories modular or beat based or systemic. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution; if we do our jobs well, all games are different. But to properly narrate any Open World story, there are four basic things we need to really, really well.

In open-world games, we encourage players to run off and play without much care for advancing a sequence of missions. This makes following a traditional 3 or 4 or 5-act plot structure challenging. We give the player control of pacing, and so events transpire on the player’s clock, relying on what Pat Hollerman aptly calls “metonymic time” (these many missions ago, that many settlements later, this many collectibles until, etc...). Plots advance to the beat of statistics.

The stories we share with our players need to embrace these constraints. But how?

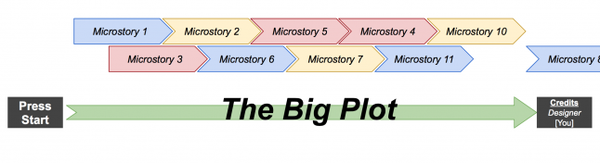

First off, the Big Plot - that mandated content that players chew through to hit the end credits - should be straightforward: crawl out of the crime world, drag down the dictator, scatter a mother’s ashes, or survive in a world gone mad. There’s a single, simple goal.

When a spectator asks, “So like, what’s the point of this game?” the player’s answer is ideally a concise statement of the Big Plot. “I’m trying to save the princess from a spikey dragonturtle” or “I have to use these little plant dudes to rebuild my ship before I run out of air.”

To help us streamline the Big Plot, additional complexity should be reserved for smaller story elements: Individual missions, quests, or encounters. Also, conversations, collectibles, documents, or environments. We’ll call these Microstories.

Microstories often have convenient beginnings and endings, or at least boundaries we can define. We can often control the player’s experience of pacing and progression during such Microstories. And because they can be enjoyed irrespective of the Big Plot, they’re a perfect fit for the Open World -- they feel like sandbox storytelling, rewarding the player for observation and engagement.

It’s also possible that a game doesn’t even need a Big Plot. Consider a game like Animal Crossing, which is comprised entirely of procedural Microstories.

By separating the simplicity of the Big Plot from the detailing of Microstories, story content becomes more digestible. Players can start, play, complete, and file away the experience without struggling to remember its finer points after every loading screen.

Yup.

People, places, and plot devices should be memorable, and not easily confused. In a typical Open World game, we want to avoid Sauron/Saruman situations wherever possible. We want our stuff to stick in our player’s brains, so we make it sticky.

Mad Max leverages the Wasteland’s weirdsmobile narrative landscape to great effect. Our hero, Max, travels across the Great White with his sidekick Chumbucket. He builds an incredible combat car called the Magnum Opus so that he can bring down Scabrous Scrotus.

Simple, memorable, weird words that catch in the crags of the brain.

Sleeping Dogs excellently invokes gang nicknames and the setting’s unique combination of English and Chinese verbiage. Undercover cop Wei Shen is hankering for a fight with Dog Eyes. He dates a woman from North Point, who is named Not Ping. He spends a lot of time working for Winston Chu, who serves as a Red Pole to Uncle Po.

Memorable.

Just as important as making things memorable is repeating them, drilling them into the player’s mind. Three is always the Good Number, but more never hurts, especially in games with tremendous scope. Characters, locations, concepts, and objects are the touchstones of a sprawling storyworld, so players should have opportunities to “touch” them often.

Check out how often we said Dimah’s name in her first two scenes in Just Cause 3:

Repetition, repetition, repetition!

As we said above, complex Big Plots can be difficult to remember and keep track of. But people are remarkably good at remembering people. Even if the main plot is convoluted or tricky or so open that it’s easily forgotten, players remember the characters they spend time with.

Consider Pagan Min, John Marston, Revolver Ocelot. Players may not remember their full arcs, but they will remember the person, and that person contributes to their overall experience of the narrative. They stick in the brain, players know what they’re about. They pursue desires and overcome challenges.

*

Stories are about people, so if we get nothing else right, we must get people right.

*GIF credit to KefkaticFanatic; original art, Square-Enix.

It’s a good goal for any Open World narrative designer to incorporate as much of the player’s activities as possible into the narrative framework.

This is (in part) why our stories often feature war-torn environments or dangerous wildernesses, and our characters are often criminals, miscreants, or rebels. These settings and occupations give them license to behave outside of the real world’s mores and codes of conduct.

Red Dead Redemption casts the player as John Marston, fairly ambiguous kinda-hero within a world of outlaws. The Wild West is untamed and dangerous, so the conventional social taboo against killing is compromised. Kill or be killed, all John cares about is getting his family back.

Mad Max features a fairly selfish hero undertaking barter-based work for other people, trying to survive long enough to build the Magnum Opus. In fact, the whole plot of the game focuses on Mad Max’s two key gameplay components: survival and vehicle combat. Awesome.

Just Cause 2 frames Rico as a violent criminal who uses his crime sprees to generate interest in local rebellious factions, then capitalizes on that to destabilize the local power structure of Panau.

In Just Cause 3, Rico takes on a more heroic bent, but his solution to the many problems he’s presented is generally, “So we blow it up!” The modus operandi of Rico’s rebellion is expressed early on: “Whatever you destroy, we’ll rebuild.” Because Di Ravello’s Medici sucks anyway, it’s a-okay with the island’s inhabitants that Rico blows up whatever needs blowing up in order to bring an end to his reign of terror.

This is the secret 5th rule - something all game developers must remember, something we often forget, especially when developing games that are all about mechanics and openness.

Gameplay is Story.

The player’s choices are the character’s choices. How do those choices affect the world? How do those choices reflect the characters? Game stories are at their best when we observe what players do, and we tell them we’re listening.

Recently, Open World games have really embraced this concept. Shadow of Mordor and Shadow of War are the most visible and recent examples. The Nemesis System embraces the player’s story, makes an effort to remember it, and sprinkles it with narrative flavor. The gameplay and these proceduralized Microstories are totally aligned. The world feels alive because the designers provide the player with even minor narrative and gameplay consequences for the actions they take.

This rule also thrives in the really small things. In Mad Max, Max and Chum talk to one another when Max runs away from the car. Totally unnecessary, but valuable for portraying the relationship between those two characters.

We should take advantage of every opportunity to show our players we’re listening to their actions and choices.

Story should be digestible so players can remember the essentials of the Big Plot and not get caught up in the tricky details. Save those for Microstories like audio logs, missions, or NPC chatter.

Story should be sticky so that the things and people and places that players need to remember will stay with them across sessions and even franchises.

Focus on memorable, engaging characters over plot. People contribute way more to the narrative experience than events.

Embrace the game’s verbs. Turn in to the things that make the game what it is, and tell the story it’s meant to tell.

Because, after all, the hidden lesson: Gameplay is story!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like