Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the latest in a series of Gamasutra-exclusive bonus material originally to be included in Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton's new book Vintage Games, we examine classic twin-stick arcade shooter Robotron: 2084 and the sub-genre of frantic games it birthed.

[In the latest in a series of Gamasutra-exclusive bonus material originally to be included in Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton's new book Vintage Games, we examine classic twin-stick arcade shooter Robotron: 2084 and the sub-genre of frantic games it birthed. Previously in this 'bonus material' series: another classic Eugene Jarvis title, Defender, as well as Elite, Tony Hawk's Pro Skater, Pinball Construction Set, Pong, Rogue and Spacewar!.]

Robotron: 2084, an arcade game developed by Eugene Jarvis and Larry DeMar at Vid Kidz and released by Williams Electronics in 1982, is without doubt one of the most difficult games ever to grace the arcades.

In terms of sheer physical and mental challenge, it is second only to the popular Defender and direct sequel, Stargate, whose history and development are detailed in bonus chapter, "Defender (1980): The Joys of Difficult Games."

Indeed, it repurposed the technology found in those games, offering a graphical style, sound effects, pacing, and difficulty familiar to fans of these earlier titles. What makes Robotron stand out from its predecessors, however, is its concrete gameplay and innovative control scheme.

Unlike Defender, where the player pilots a spaceship across an abstract, scrolling planet, Robotron is more down-to-Earth, putting the player in the shoes of an avatar whose movement is limited by the edges of a single screen.

The player is tasked with the grim, desperate, and ultimately futile task of saving the last family of Humanoids.

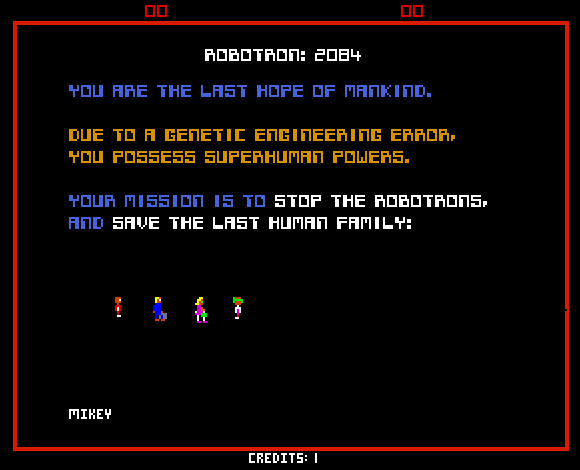

A scene from Robotron: 2084's lengthy attract screen, explaining the rather superfluous plot.

Unlike Defender's Humanoids, who were scarcely recognizable as such[1], Robotron's family is distinctly human, complete with clothing and accessories. However, perhaps the biggest differentiator from the earlier games is the breakthrough control scheme -- instead of a single joystick and multiple buttons, Robotron features two independent eight-way joysticks: one for movement and the other for shooting.

This control scheme is immediately intuitive -- a minimalist design and virtuoso implementation that stands in stark contrast to the somewhat bewildering scheme of Jarvis's earlier game.

Robotron features the same attract screen format as Defender, describing the story and how to play, though going into much greater detail. The quick version of the story casts you as a super-powered genetic engineering error, or mutant, whose job is to protect clones of the "last human family," consisting of "Mommy," "Daddy," and "Mikey" (young son). The family is being pursued by the Robotrons, a collection of robot enemies that includes "GRUNT,"[2] "Hulk," "Enforcer," "Brain," and "Tank" variations.

Although the detailed backstory is nice, it's really incidental to an action game that is not even winnable. The developers realized, though, that "all this mindless carnage would need to be held together by some sort of plot, and that's where the nuclear family and robots came in."[3]

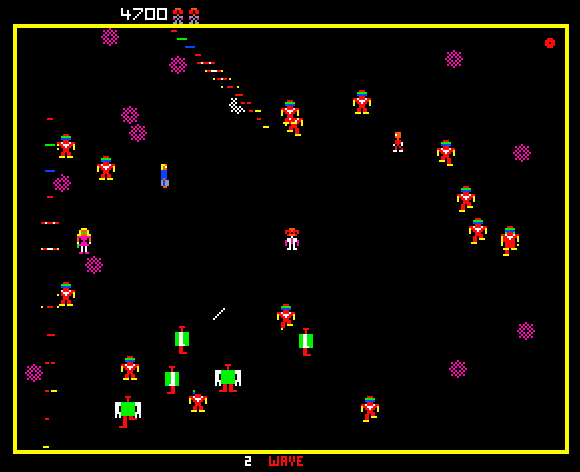

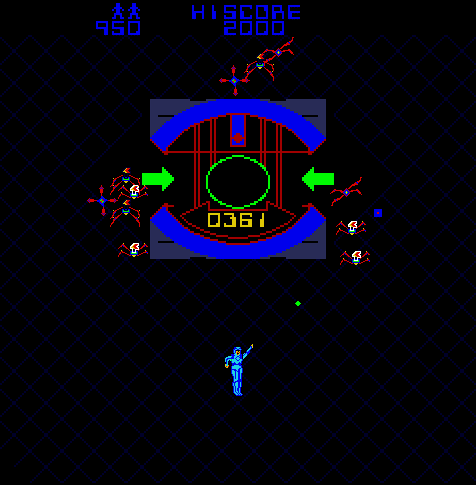

A typically intense scene from Robotron: 2084.

The game takes place on a single screen with random placement of Humanoids and Robotrons. The screen is also populated with both fixed (such as the deadly "Electrodes") and moving objects. The moving objects include units that create some of the Robotrons, like "Sphereoids," which produce Enforcers, and "Quarks," which produce Tanks. Humanoids are rescued whenever the player's character runs into them, but walking into pretty much anything else causes instant death.

Once all of the Humanoids have been rescued, play continues on a new, slightly more difficult level, with an increase in both speed and number of enemies. Most enemy types fire back and are deadly to the touch (for both the wandering Humanoids and the player), and some are simply invulnerable. The game is famous for its fast-paced, even frantic, intensity.

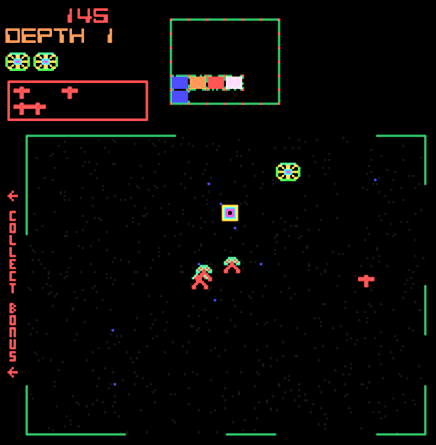

Screenshot from Taito's Space Dungeon arcade game from 1981, which used a dual-joystick configuration before Robotron: 2084, but failed to attract much gamer interest to its combined shooting and treasure-hunting gameplay.

[1] See Choplifter author Dan Gorlin's quip in bonus chapter, "Defender (1980): The Joys of Difficult Games".

[2] Standing for Ground Roving Unit Network Terminator.

[3] http://www.isomedia.com/homes/blutz/emurumor/rotw4.htm.

The basic gameplay of Robotron was most inspired by the Berzerk arcade game, which we discussed in the book's Chapter 2, "Castle Wolfenstein (1981): Achtung! Stealth Gaming Steps Out of the Shadows."[4]

According to Jarvis, "I was a great fan of the game Berzerk, and the frustration of that and all other single-joystick games was that you have to move toward an enemy in order to fire in that direction. Berzerk had a mode that alleviated that somewhat in that you held the fire button down, the character would stand still and then a bullet could be fired with the joystick in any direction. So essentially in that mode the joystick fires the bullet. I just put on a separate joystick to fire bullets."

Jarvis toyed with the idea of a more passive game with no firing, where you would kill the robots by making them walk into Electrodes, but soon realized that this was not the path to gaming enlightenment:

"It was fun for about fifteen minutes, running the robots into the electrodes. But pacifism has its limits. Gandhi, the video game, would have to wait; it was time for some killing action. We wired up the 'fire' joystick and the chaos was unbelievable. Next we dialed up the Robot count on the terminal. 10 was fun. How about 20? 30, 60, 90, 120! The tension of having the world converge on you from all sides simultaneously and the incredible body count created an unparalleled adrenalin rush. Add to it the mental overload of a truly ambidextrous control, and it was insanity at its best."[5]

The Atari 5200 received the only home conversion of Space Dungeon. The addition of the pictured joystick coupler made the experience more authentic and also worked great with the Robotron: 2084 cartridge.

The result was that Robotron was one of the very first, all-out, nonstop action games that truly resonated with the general public. Though unforgiving in its intensity and requiring an almost Zen-like state-of-mind to rack up a respectable score, the game was perhaps the first evolution of that elusive "perfect" twitch game, an all-you-can-kill buffet.

The nonstop action and wave after wave of enemies were balanced by the basic human need to nurture, in the form of rescuing the Humanoids. It perhaps speaks even more pointedly to the human condition that death is inevitable and unavoidable, as in the arcade classic nuclear missile defense game, Missile Command (Atari, 1980).

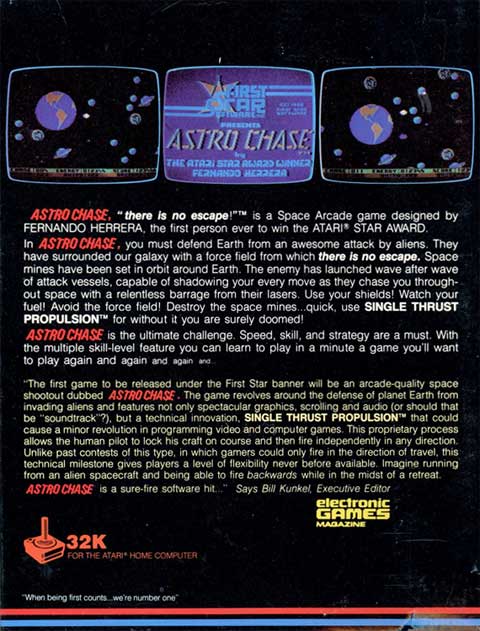

Box back for the Atari 8-bit version of First Star Software's Astro Chase, which offered what it claimed was revolutionary "single thrust propulsion," but was really just an option for the player to lock in a movement direction while firing in another. It was a nice concession to the limitations of home controllers, but still not an ideal replacement for the preferred Robotron dual joystick control scheme.

As described briefly in book Chapter 18, "Super Mario 64/Tomb Raider (1996): The Third Dimension," it wouldn't be until the idea (or discovery) of using dual analog sticks to control 3D games became an option in the late 1990s[6] -- often using one stick for movement and the other for aiming or camera control -- that using two controls simultaneously became common practice.[7]

Prior to that, dual, simultaneous controls were used sparingly outside of the arcade, for mostly practical reasons. As stated by Jarvis, "Robotron has always been frustrating in non-arcade versions because of the lack of the dual-joystick control. Because of the intensity of play the game is very athletic, and it is very nice to have a 300-pound arcade cabinet stabilizing your joysticks. Without true dual fixed joysticks, the game can be quite frustrating in console and PC versions."[8]

A scene from Bally Midway's arcade game, Tron, based on the cult favorite movie. Gameplay consisted of various scenes, including Light Cycles, MCP Cone, Tanks, and the pictured Grid Bugs. Tron made simultaneous use of a spinner and a joystick with a fire button trigger.

Nevertheless, home versions of Robotron-style dual-control games typically took one of two basic approaches to the challenge. Some games, like the home translations of Vanguard,[9] would simply combine movement and firing into one controller -- where you moved, you fired. This typically changed the basic gameplay. In the case of Vanguard, the arcade player was able to move with the joystick and fire separately in one of four cardinal points with the buttons.

[4] Other suggestions either from Jarvis himself or others include Chase on the Commodore PET computer and Robots for UNIX, each of which shares similarities with the later Berzerk.

[5] http://www.dadgum.com/halcyon/BOOK/JARVIS.HTM.

[6] More or less after the release of Sony's DualShock in 1998 for their PlayStation console.

[7] That is, outside of the mostly first-person shooter computer games from a few years earlier. Their interfaces eventually developed into the now-common mouse/keyboard combination. See book Chapter 5, "Doom (1993): The First-Person Shooter Takes Control," for more on this.

[8] http://www.dadgum.com/halcyon/BOOK/JARVIS.HTM.

[9] A 1981 Centuri release in the arcade, and a 1982 Atari release for the Atari 2600 VCS and 5200. The home versions would also allow the player to shoot forward continuously if they so chose.

Other games though, like Synapse's Survivor (1982; Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64), would offer a second option -- a second controller allowed independent firing. Unfortunately, without some way to hold the two controllers together, this meant a second player was needed to operate the controls. As described in Chapter 2 of the book, if you did have the benefit of a second player to work with, it could create some crazy fun and at the very least, with proper coordination, allow for higher scores, as players could properly evade in one direction, while firing in the other.

A scene from Tradewest's 1986 arcade game, Ikari Warriors, which made use of a rotary joystick, allowing for movement in eight directions and aiming rotation. Rotary joysticks can be considered a single-controller compromise from the dual-joystick format.

Of course, another option for an enterprising gamer was to build his or her own custom coupler, but so few games offered independent movement and firing options that it typically wasn't worth it. Although some third-party companies offered joystick stands and bases, these were not necessarily intended to hold the controller down in lieu of a player's second hand.

Atari released a coupler for its Atari 5200 console[10] along with cartridges like Robotron: 2084 and Space Dungeon,[11] but it too received little use otherwise. Around the same time, Coleco fans had holders for both of the ColecoVision's joystick controllers integrated into the platform's roller controller (trackball), but again, no software really took advantage of the setup.

Furthermore, the stiff joystick knobs offered too much resistance. This problem of resistance was not an issue on the Atari 5200, as that system's limp, non-self centering analog joysticks didn't require a great deal of weight to hold down when in motion.

A scene from Eugene Jarvis's and Mark Turmell's hit 1990 Williams arcade game, Smash T.V., which brought the dual-joystick gameplay of Robotron: 2084 to two simultaneous players in a violent game show competition set in 1999. Many home conversions of this popular game followed.

In the late 1980s, systems like the NES offered handheld gamepads with flat directional pads (d-pads) instead of raised joysticks, and coupling -- no matter how clever -- was no longer a viable option.[12] D-pads simply didn't offer the same type of stable rotational ability as joysticks did, so development of home games with independent movement and firing options was further stymied.

A scene from Mark Turmell's 1991 Midway arcade game Total Carnage, which played liked a more free-roaming Smash T.V.

[10] Released 1982.

[11] A superb translation of the obscure 1981 arcade game from Taito.

[12] Joysticks, often with weighted bases, were available, but were obviously no longer standard equipment.

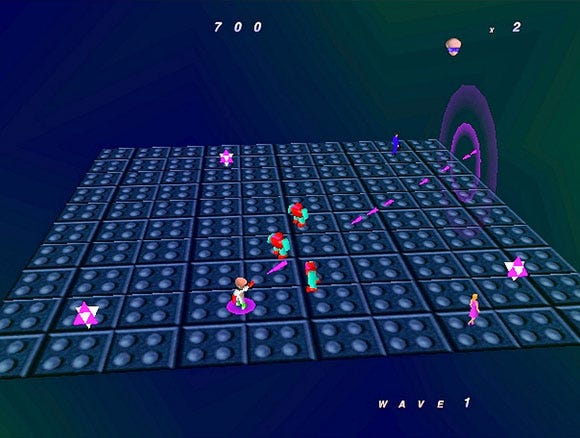

This would begin to change again in the 1990s, as systems with control pads featuring button layouts in the cardinal points, like the Super Nintendo and Sony PlayStation, began to appear. For instance, the direct-to-home sequel, Robotron X from Crave (1996; PC, Sony PlayStation),[13] not only took the visuals into 3D, but also allowed a single player to independently fire using the cardinal point button layout in place of a second joystick.

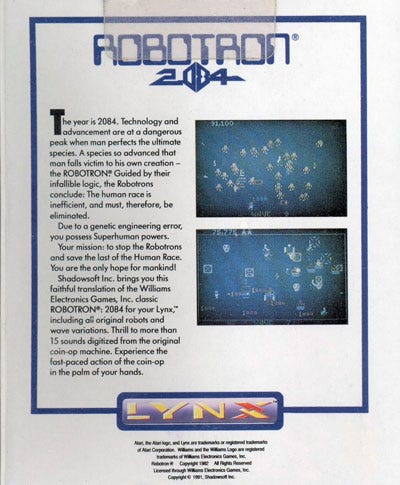

Box back for the 1991 Atari Lynx version of Robotron: 2084. The Lynx version, much like most other home conversions, offered several different control methods, but nothing approaching the quality of the original dual-joystick control scheme.

Of course, outside of the computer gaming world's favored mouse/keyboard combination, it would take the standardization on dual controls on the console side, and then another revolution of sorts -- downloadable games -- for the real explosion of games with simultaneous independent control to happen.

All three current consoles, Microsoft's Xbox 360 and Sony's PlayStation 3 with their standard controllers and respective Xbox Live and PlayStation Network services, and Nintendo's Wii with Wii Remote/Nunchuck combination and Wii Shop Channel, meet these basic criteria. It's a happy coincidence, of course, as modern controllers are designed (at least partially) for the many 3D games that require movement independent of aiming or looking.

Robotron 64 was the mostly improved Nintendo 64 update to the earlier Robotron X for PC and Sony PlayStation, which itself was a 3D reimagining of Robotron: 2084.

Screenshot from Sony's Jet Li: Rise to Honor for the Sony PlayStation 2, a mediocre action game from 2004 that was notable for primarily using the system's left analog stick to move and the right analog stick to attack.

The Xbox 360's Xbox Live Arcade seems to represent the natural evolution of the arcade. There have been an abundance of intense dual-joystick games like Assault Heroes (Wanako Studio, 2006), Crystal Quest (Stainless Games, 2006), Mutant Storm Empire (PomPom Games, 2007), Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved 2 (Bizarre Creations, 2008) and Wolf of the Battlefield: Commando 3 (Capcom, 2008).

Even Robotron: 2084 received a faithful emulation of the original on the service in 2005 from Midway, but also featured several updates, including a new online co-op mode.

Screenshot from 2005's Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved, found on the Microsoft Xbox 360's Xbox Live Arcade. The trippy shooter leads a wide range of games on the service that use a straightforward Robotron-style control scheme.

Despite the game's enduring popularity and adoption of both its control format and frenetic style in countless games, Robotron's legacy is broader still. Like Defender before it -- which proved that the public was ready for more complex games -- Robotron proved that the public was ready for the type of simultaneous control that is a hallmark of modern gaming, where controlling both movement and aiming or camera control have become requirements for effective play within today's 3D games.

Robotron may have been challenging and even intimidating, but gamers everywhere were ready to grasp the challenge -- with both hands.

[13] Released in 1998 as Robotron 64 for the Nintendo 64.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like