Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How did user-created content start? Bill Budge's classic 1983 Pinball Construction Kit was one of the earliest titles to focus on it, and this Gamasutra article looks at its genesis in-depth.

[Gamasutra presents its second exclusive web-only bonus chapter from Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton's forthcoming book Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time.

Here, the duo presents a history of Pinball Construction Set, one of the earliest and most accessible examples of a game that engenders user-created content.]

In 1981, when it was still possible to sell commercial computer games in plastic baggies,[1] Bill Budge released his latest game, Raster Blaster, for the Apple II. It was published through his own company, BudgeCo Inc., a cooperative venture formed with his sister.

Raster Blaster was a fast-paced, single-screen pinball game inspired by Williams's Firepower pinball machine. Although Raster Blaster was a critical and commercial success, its greatest claim to fame was that it provided Budge with the experience necessary to develop his legendary follow-up, Pinball Construction Set (PCS), subtitled "A video construction set from BudgeCo".

BudgeCo's Raster Blaster.

BudgeCo's Raster Blaster.

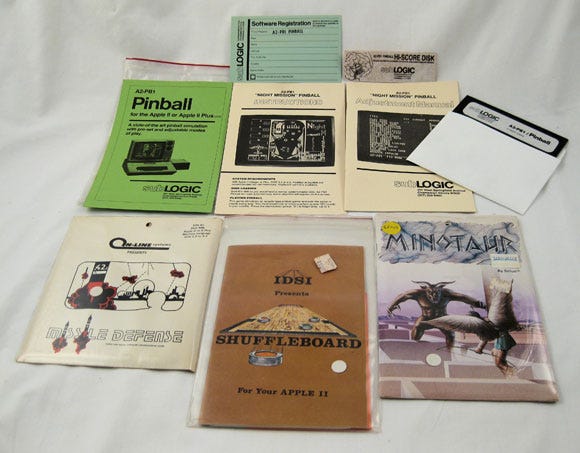

Right up to the early 1980s, commercial computer software often came in plastic baggies or small cardboard folders. Note the expanded contents from the zipper storage bag of subLOGIC's configurable Pinball (also known as Night Mission Pinball, 1982) game from Bruce Artwick of Flight Simulator fame.

Right up to the early 1980s, commercial computer software often came in plastic baggies or small cardboard folders. Note the expanded contents from the zipper storage bag of subLOGIC's configurable Pinball (also known as Night Mission Pinball, 1982) game from Bruce Artwick of Flight Simulator fame.

The small cardboard folder included with the disk describes the game well: "The Pinball Construction Set contains the pieces and tools to make millions of hi-res video pinball games. No programming or typing is necessary. Just take parts from the set and put them on the game board. Press a button to play! Use the video tools to make borders and obstacles. Add game logic and scoring rules with the wiring kit. Create hi-res designs and logos using the BudgeCo magnifier. Color your designs with the paint brush."

The fact that Budge's own Raster Blaster could be recreated and even surpassed with PCS was enticing to anyone who had dreamed of making a virtual pinball game. Exciting stuff even today, it was downright groundbreaking in 1982 -- particularly considering that the Apple II had just 48K of RAM.

Partial scan of the exterior folder from BudgeCo's original release of Pinball Construction Set, featuring a very literal cover design.

Partial scan of the exterior folder from BudgeCo's original release of Pinball Construction Set, featuring a very literal cover design.

Although PCS was another critical and commercial success for BudgeCo, Budge and his sister were soon overwhelmed with the demands of running a software publishing business in an increasingly sophisticated and competitive marketplace.

Budge agreed to work with Trip Hawkins and his fledgling startup, Electronic Arts (EA), whose goal at the time was to promote the idea of developer as "software artist" (or superstar), while at the same time presenting computer games in attractive, professional packaging. Computer games had remained on the margins of popular culture, and Hawkins's goal was not just to sell his own games but to sell gaming as a worthwhile medium.

Thus, in 1983, Electronic Arts published Pinball Construction Set in the company's iconic record album-style packaging with slick cover art, complete with a greatly expanded (though arguably superfluous) instruction manual. The game was eventually ported to the Apple Macintosh, Atari 8-bit, Coleco Adam,[2] Commodore 64, and PC. It was a big success for EA and instrumental in establishing the publisher's reputation for quality products.

Exterior (top) and interior (bottom) views of the unfolded album-style packaging for the Electronic Arts version of Pinball Construction Set, which portrayed Budge as an artistic superstar and his product as the revolution that it was.

Exterior (top) and interior (bottom) views of the unfolded album-style packaging for the Electronic Arts version of Pinball Construction Set, which portrayed Budge as an artistic superstar and his product as the revolution that it was.

---

[1] The Ziploc® brand or plastic zipper storage bags.

[2] As part of The Best of Electronic Arts, along with platformer Hard Hat Mack.

How did one go about constructing a virtual pinball game with these humble machines? Budge took a pragmatic and surprisingly modern approach to PCS' interface, allowing for intuitive drag-and-drop construction, primarily with a joystick, though keyboard and other control options -- like the KoalaPad graphics tablet[3] -- were available on some platforms.[4]

As Budge recalls, "I was exposed to GUIs at Apple, and I had the pinball simulation from Raster Blaster. I saw that it would be a small step to do a construction set. This was the kind of program I liked, since there was no game to write. But it was a lot of work, since I had to implement file saving, a mini sound editor and a mini paint program."[5]

The player simply guided a disembodied hand, complete with pointing finger for selection, to draw, color, and drag and drop the various table elements onto the board.

As Armchair Arcade member "Rowdy Rob" recalls, "PCS was, back then, a groundbreaking program. It had an easy, intuitive, and Mac-like interface, and even without a mouse, it was a snap to place various targets, bumpers, and flippers on the table. The flexibility of the program allowed you to create very odd-looking pinball games, and was a great experimental tool. This 'game' was definitely a high point in the history of Apple II games. You could 'snap together' a cool pinball game in under an hour, and your friends could play your games for longer than it took you to create the game! How rare is that?"[6]

Most conversions, like the Commodore 64 version pictured on the right, were straight ports from the Apple II version (left), and -- although they played the same -- often suffered visually.

Most conversions, like the Commodore 64 version pictured on the right, were straight ports from the Apple II version (left), and -- although they played the same -- often suffered visually.

PCS was one of the very first "software toys," a "game" in which the fun is exploring one's own creative possibilities.[7] It also established several precedents that made it easier for novice users to achieve their vision. Everything took place from a single screen with a consolidated interface, and users could play-test their boards at any point in the development process.

The title also came with a complement of sample tables for immediate play or inspiration. Though a bit clunky by modern standards, the tables featured physics-based rules and allowed for many realistic and interesting features like multiple balls.

There were also more fanciful options. Rowdy Rob reminisces, "I remember creating a pinball game where, instead of launching the ball up the right side (which is standard pinball procedure), I created a table where the ball launched up the middle of the table, and most of the action took place on either side of the ball-launcher. My computer club compatriots liked the idea so much that they copied the idea in several of their own pinball creations, which irritated me back then ('they ripped off my idea!'), but looking back, I should have been flattered. The point is that the program was that flexible; crazy pinball tables could be created and playtested without fear of crashing the program."

Mirroring EA's future business model, the company tried to build on the basic ideas established by the success of PCS and released titles with similar functionality from other developers, including Music Construction Set (1984; Apple II, Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64, PC, and others), Racing Destruction Set (1985; Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64), and Adventure Construction Set (1985; Apple II, Commodore 64, Commodore Amiga, PC).

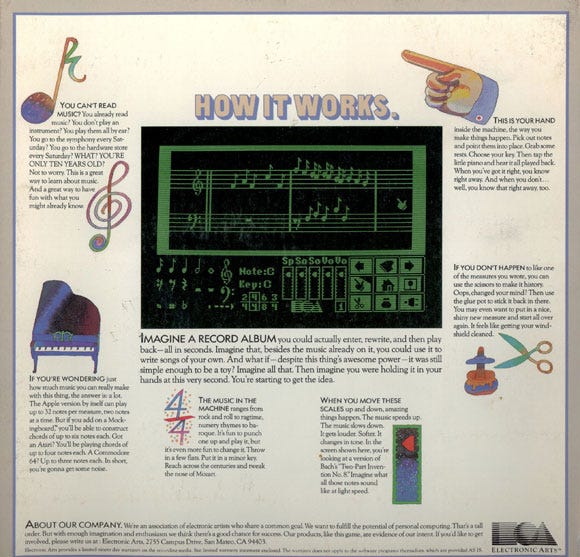

Back of the box for Music Construction Set, Apple II version.

Back of the box for Music Construction Set, Apple II version.

Will Harvey's Music Construction Set (MCS) was really intended more for education than entertainment, but nevertheless was sold alongside the top such titles of the day and proved a popular diversion. Today, we'd probably call it "edutainment." As a music composition notation program, users could drag and drop notes right onto the staff, play back their creations, and print them out. What PCS did for approachable game development, MCS did for approachable song creation, spawning a series of increasingly sophisticated knock-offs.

Back of the box for Racing Destruction Set, Commodore 64 version.

Back of the box for Racing Destruction Set, Commodore 64 version.

Rich Koenig's Racing Destruction Set (RDS), was a split-screen, isometric-perspective racing game that could be played in either racing or destruction modes, the latter allowing for offensive weapons like oil slicks and landmines in order to impede opponents' progress. Available vehicles included a variety of cars, including a jeep and lunar rover, as well as motorcycles. Where RDS really shined, however, was the ability to modify various in-game elements, like gravity and vehicle components, as well as designing full courses with choice of terrain.

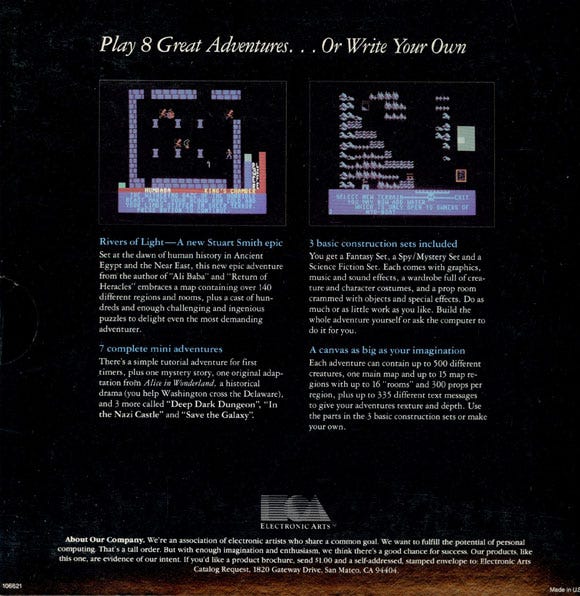

Back of the box for Adventure Construction Set, Commodore 64 version.

Back of the box for Adventure Construction Set, Commodore 64 version.

Finally, Stuart Smith's Adventure Construction Set (ACS), the most advanced release in this class from EA, allowed gamers to craft complete role-playing games. ACS came with various toolkits to allow the creation of science fiction, spy or fantasy-themed games, and included some sample games to get users started.

Although naturally not as accessible as PCS, ACS nevertheless succeeded in its goal of allowing anyone with enough gumption to create their own top-down, side-perspective[8] RPGs, similar to Ultima (book Chapter 23, "Ultima (1980): The Immaculate Conception of the Computer Role-Playing Game") or Smith's earlier creations, like Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (Quality Software, 1981; Apple II, Atari 8-bit).

For those who either didn't want to make their own games or gave up in the middle of the process, ACS could either create a game from scratch or finish building a game already started.

---

[3] The KoalaPad could work with the included stylus or a user's finger.

[4] The Apple Macintosh platform could make use of that system's standard mouse for a more modern analog.

[5] http://www.dadgum.com/halcyon/BOOK/BUDGE.HTM.

[6] http://www.armchairarcade.com/neo/node/1966#comment-5170.

[7] More specifically, a software toy's primary goal is to provide either the parts or allow the creation of the parts to build a game. Compare this to a "virtual playground," like The Sims in Chapter 22, "The Sims (2000): Who Let the Sims Out?" where the primary goal is to essentially play with or manipulate premade elements, with less focus on creativity and creation, and "sandbox" games, like Grand Theft Auto III in Chapter 9, "Grand Theft Auto III (2001): The Consolejacking Life," where the player is able to move about a large environment and perform a wide range of typically realistic activities, but with a primary focus on accomplishing various goals and activities over any type of creative or creation possibilities.

[8] As in Castle Wolfenstein; see Chapter 2, "Castle Wolfenstein (1981): Achtung! Stealth Gaming Steps out of the Shadows."

Of course, in the mid 1980s, nearly every personal computer came with a default programming language. At this time, many computer manufacturers hyped up these features as a key selling point. Typically, a personal computer shipped with BASIC,[9] which offered virtually unlimited development possibilities for those willing to put the time into learning its syntax and program structure.

Unfortunately, BASIC -- an interpreted language -- is designed to make programming easier, but not necessarily more efficient. Though far easier to master than a platform's respective machine or assembly language, BASIC is often slow and unsuitable for games with sophisticated audiovisuals.

Early on, however, clever developers released software to help augment users' programming efforts, like Bruce Artwick's subLOGIC A2-3D1 Animation System (1979) for the Apple II, a powerful assembly language package containing three development modules useful in the creation of Flight Simulator (see book Chapter 8, "Flight Simulator (1980): Digital Reality"); Penguin's The Graphics Magician (1982; Apple II, Commodore 64, and others), aimed at those who wanted to integrate high-quality graphics into their own code; and Epyx's similar Programmers' BASIC Toolkit (1985) for the Commodore 64, which promised, "Assembly Language Graphics with BASIC Convenience."

Unfortunately, none of this multitude of often-useful products was targeted at the more casual enthusiast who wanted to make games.

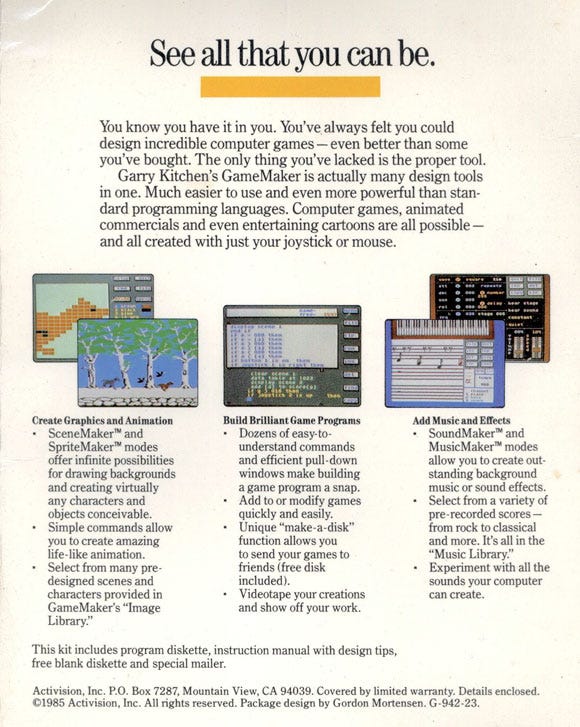

Back of the box for Gary Kitchen's GameMaker, Commodore 64 version.

Back of the box for Gary Kitchen's GameMaker, Commodore 64 version.

Fortunately, a series of later titles took the concepts in PCS and applied them to other types of game development. These included Adventure Master (1984; Apple II, Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64) from CBS Software, for creating simple text and text and graphics adventures (or "interactive fiction"; see book Chapter 25, "Zork (1980): Text Imps versus Graphics Grues"); Adventure Creator (1984; Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64, and others) from Spinnaker Software, a simplified version of Smith's later ACS; and Gary Kitchen's GameMaker (1985; Apple II, Commodore 64) from Activision, which consisted of a series of intuitive development modules for nearly any type of game (additional libraries like "Sports" were sold separately).

As with PCS, all of these products faced technical limitations that restricted the sophistication of the users' creations, but they nonetheless provided a welcome avenue for creative individuals unwilling or unable to master traditional programming languages.

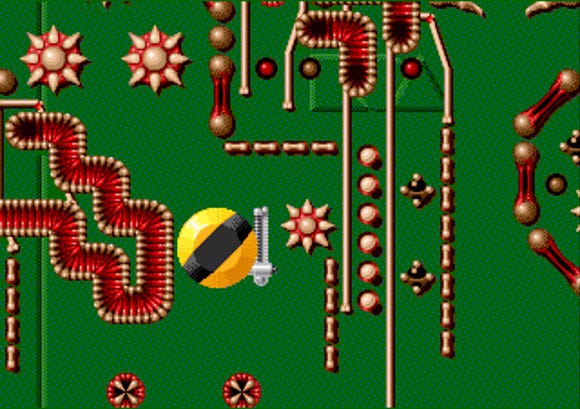

Screenshot from Virtual Pinball for the Sega Genesis, showcasing the unusual design aesthetic.

Screenshot from Virtual Pinball for the Sega Genesis, showcasing the unusual design aesthetic.

After retiring from videogame creation in the mid 1980s after burning out from the overwhelming pressure of trying to outdo PCS, Budge tried again with BudgeCo through EA with the 1993 release of Virtual Pinball for the Sega Genesis.

Says Budge, "I wanted to get back into game programming. EA and I thought this might do okay on the Genesis. I liked the challenge of the restrictions (no keyboard, disk, mouse) and the power (fast graphics, 68000 processor) and thought I could do a good job. It turned out great, in my opinion. I made the collision detection and physics more robust and it got me started on my current path, to develop technology for 3D graphics and modeling."[10]

Unfortunately, Budge's program was at the wrong place at the wrong time. Audiovisual expectations were higher than ever before, and the Sega Genesis already featured several excellent pinball titles. Virtual Pinball went straight down the middle and into the drain. A review by Benjamin Galway describes some of the downsides:

Being able to design unique pinball tables is the real draw of the game, even if the actual pinball play isn't up to snuff. Players can take any of the eighteen preloaded tables into the game's Workshop or start from scratch, then save their creations in the cartridge's generous ten memory slots. Tables are assembled via a cursor that can drop or destroy objects, selected via a basic menu. There is a handful of bumpers, flippers, walls, targets, and other items to be placed at the user's discretion along with six different styles available for the parts (Blueprint, Classic, Pool, Gore, Classic II, and Droid) and a dozen backgrounds adding some variety to the tables. Unfortunately, it's just not enough to sustain any long-term interest in the game. Enjoyment rests largely on one's ability to be creative with the construction tools, so anyone lacking an imagination will be at a loss. The Workshop is a bit lacking as well with its inability to allow for curved ramps and walls, grouping of targets instead of lumping them all together, and most any other concept to help add depth to the tables.[11]

---

[9] Standing for Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code.

[10] http://www.dadgum.com/halcyon/BOOK/BUDGE.HTM.

[11] http://www.sega-16.com/review_page.php?id=952&title=Virtual%20Pinball.

Interplay's The Bard's Tale Construction Set (1991) put all the creative flexibility of The Bard's Tale series of popular role-playing games at a player's fingertips. Finally, virtual dungeon masters could easily create high-quality adventures for their friends.

Interplay's The Bard's Tale Construction Set (1991) put all the creative flexibility of The Bard's Tale series of popular role-playing games at a player's fingertips. Finally, virtual dungeon masters could easily create high-quality adventures for their friends.

Semipro development tools have often allowed sophisticated users to do amazing work with popular titles. Examples include Doom's fan-made Doom Editing Utility (DEU) from 1994, which was useful for making the game's WADs,[12] or file packages that contained levels, graphics and other game data, and Bioware's RPG Neverwinter Nights (2002; Apple Macintosh, Linux, PC), which came with the Aurora toolset for complete custom module creation.

However, these tools -- though certainly powerful -- still represented a daunting challenge for the average computer gamer.

Further, although there have certainly been occasional console games that have allowed level creation or modification, like the course designer in Nintendo's Excitebike (1984; Arcade, Nintendo Entertainment System, and others), or even complete game creation, as in Agetec's RPG Maker 3 (2005; Sony PlayStation 2), there have been few attempts other than the failed Virtual Pinball to bridge the middle ground that PCS so successfully made its own -- that is, until the 2008 release of Sony's LittleBigPlanet for its PlayStation 3 system.

Sony's LittleBigPlanet offers robust construction and collaboration features.

Sony's LittleBigPlanet offers robust construction and collaboration features.

Superficially, LittleBigPlanet is an attractive but simple side-scrolling platformer[13] starring a cute, anthropomorphic beanbag. However, the game's true potential is realized in its level editing and sharing tools, which let up to four simultaneous players create original stages, objects, and enemies in real time, either together in person or online.

Ultimately, it's the platform's online capabilities and ubiquitous hard drive that help bridge the gap between the inability to share creations and the limits of cartridge-based storage of the past, paving the way for a bright future for software toys in general, regardless of platform.

Screenshot from the flexible Game Maker, version 7, which allows for both drag-and-drop construction and more traditional programming techniques.

Screenshot from the flexible Game Maker, version 7, which allows for both drag-and-drop construction and more traditional programming techniques.

Still recognized today, Budge and EA received a belated Technology & Engineering Emmy Award in 2008 for PCS, alongside first-person shooter Quake (see book Chapter 5, "Doom (1993): The First-Person Shooter Takes Control") and virtual world Second Life (see book Chapter 24, "Ultima Online (1997): Putting the Role-Play Back in Computer Role-Playing Games"), in the User-Generated Content -- Game Modification category.

Nevertheless, we've yet to realize Budge's dream of a "construction kit construction kit," with which even a total novice could produce a professional-quality product.

Nevertheless, we seem to be getting closer with newer programs like ClickTeam's The Games Factory 2 (2006; PC) and Mark Overmars' Game Maker (starting in 1999; PC), both of which offer a combination of drag-and-drop object-/event-based programming with traditional coding and scripting techniques.

Perhaps one day soon it will be someone's creative vision -- not their mastery of programming -- that brings the next winning game idea to fruition.

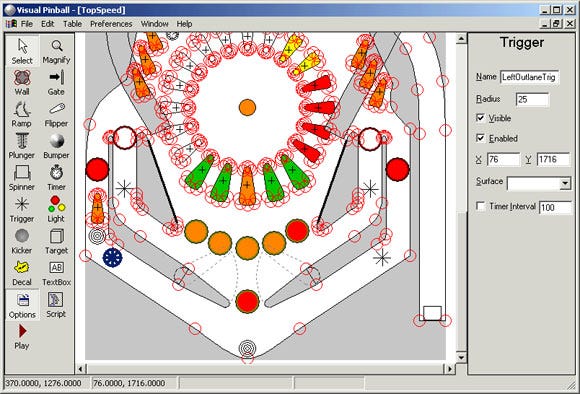

Visual Pinball is the most popular of the modern day successors to Pinball Construction Set, and consists of an emulator, simulator and editor (shown) that allows users to create and play recreations of pinball machines. Despite having something of a high learning curve for everything from setup to construction, this non-commercial application is extremely flexible, inspiring the creation and recreation of thousands of tables.

Visual Pinball is the most popular of the modern day successors to Pinball Construction Set, and consists of an emulator, simulator and editor (shown) that allows users to create and play recreations of pinball machines. Despite having something of a high learning curve for everything from setup to construction, this non-commercial application is extremely flexible, inspiring the creation and recreation of thousands of tables.

To read the first chapter in this series, The History of Pong, please click here.

---

[12] As previously mentioned, this stands for "Where's All the Data?". See book Chapter 5, "Doom (1993): The First-Person Shooter Takes Control," for more on Doom.

[13] See book Chapter 19, "Super Mario Bros. (1985): How High Can Jumpman Get?" for more on the platforming genre.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like