Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

A small practical study into whether or not fighting games provide sufficient learning tools to introduce new players to their archaic control schemes.

“Over the years, I personally feel that fighting games became too technical. Most people don’t want to study a game before they start having fun. While there is certainly an audience for that technical part, the reality is, is that people should have fun when they first start playing the game. We’re just trying to make things more accessible and easier to do so that more people can enjoy it. That was also our biggest challenge, appealing to both demographics. The hardcore tournament guys are the ones that are the most vocal online and the loudest.”

– (Boon, 2013) co-creator of ‘Mortal Kombat’

Fighting games certainly don’t have the reputation for being all about learning, but when one breaks down the appealing factors of the genre, it’s apparent that the sense of fulfilment they provide is based entirely on mastery. The selling point of the entire fighting game genre is its immediacy of player v player competition. To an outsider, the games may appear overly simplistic, featuring just two characters that only move depending on the position of the opponent. Despite the lack of context-altering factors such as equippable items and the inclusion of more than two players, a well made fighting game still requires the players to make rapid judgements, adapt to different situations and understand the nature of every character. What really separates fighting games from other competition-driven genres is their almost stubborn reliance on antiquated control schemes which all have roots in the arcade systems of the early 90s. The genre's most famous breakthrough- Street Fighter II- featured an eight-way joystick with 6 buttons (which at the time was considered excessive). Grab any modern fighting game that has a competitive scene and it will be able to work with this out-dated controller. Fighting game design has not evolved with controller changes. Rather than utilise a dedicated button for special attacks, fighting games still use quarter-circle joystick motions for throwing projectiles etc. These unusual control commands seem to be one of the largest factors for alienating newcomers. First person shooters translate the mouse/joystick movements into head movements to look around the world. Games that feature in-direct unit control (such as in an RTS) mimic the interface used by desktop operating systems. While there is logic to fighting game control schemes, the question is why developers choose not to change with the times and use something most modern players will recognise and understand and utilise the buttons available on a modern controller.

The most basic explanation is that by changing controls, developers risk alienating the audience they already have. Veterans of the genre are well adjusted to these schemes. Any attempt to deviate from the norm may be met with accusations of 'dumbing-down' and make take credibility away from competitive play. Fighting game commands often cross different franchises as well. Despite not reaching the budgetary highs of games like DOTA2, fighting game competitions are also thriving from the ease of Internet streaming to reach an audience of new spectators. One advantage fighting games like Street Fighter IV and Tekken Tag Tournament 2 have over DOTA2 is that their immediacy makes them more accessible to viewers. One may not understand the importance of every combo and counter-attack but it is very easy to understand that the two large lifebars at the top of the screen determine who is winning. These streams are a good source of exposure and if accepted by the fighting game community can spread positive word-of-mouth. For developers, it is probably safer to appease those already invested than risk losing them to attract a new market. The one exception is the Super Smash Brothers series which most likely managed to still capture an audience with the strength of Nintendo brand recognition. With this scenario in mind, it is clear that rather than change the traditional controls, the games must introduce new players to the traditional controls.

For the casual player entering the genre with little to no experience, the control scheme seems to exist in its own bubble of techniques rarely seen in other genres. To truly appreciate a fighting game, one must surmount a learning curve; and fighting games seem at odds with this notion as they rarely provide decent tutorials in game. While most genres seem to have extensive tutorials (many of which are forced upon the player during story progression) even the most popular fighting game franchises seem to be very lacklustre in providing the same introductory tools for the player. To actually investigate the legitimacy of this observation I conducted a small study. Using the games that appeared in the Evolution Fighting Game Tournament in 2013 as a sample, I had two novice fighting game players work their way through any tools that were available. These games were Super Street Fighter IV: Arcade Edition 2012 ver, Tekken Tag Tournament 2, Mortal Kombat (9), Injustice: Gods Among Us, Persona 4 Arena, Street Fighter X Tekken, Ultimate Marvel Vs Capcom 3 and The King of Fighters XIII.

Methodology

The games were played by two people with an active interest in gaming as a form of entertainment but also with somewhat little experience with the fighting game genre. This is not intended to be a full-scale practical study to represent the entire gaming market but rather an attempt to obtain the perspective of a novice when analysing the game modes. With this being said, it must be made clear that these players are not wholly inexperienced all fighting games but rather representations of the ‘casual’ fan with a passing interest at most, which differentiates them from the more avid members which make up the fighting game community.

Some games in the sample have multiple teaching tools. I shall use the most ‘base’ tutorial system available. For example although it has a mode teaching character-specific combos, the game Injustice will ignore this in favour of the basic tutorial as it teaches more fundamental skills than elaborate combos. Likewise, some games also lack basic tutorials. In these games the closest mode to a tutorial will be used instead such as Street Fighter IV’s combo trials.

All of the play sessions will be recorded as videos for future reference. A consent form will permit the use of this footage for the study. The consent form will also include a multiple-choice question to determine what their prior experience with each game is.

Each participant will play the games in a randomised order as skills learnt in one game can potentially transfer to another. The sessions will have a 15-minute ‘dedication time’. This means that the sessions will run for a minimum of 15 minutes. At this point I will ask the participant if they wish to continue or not. This is to roughly simulate the dedication a player may have trying a new game after deciding to pay for it. The option to freely quit at any time could potentially make some sessions end prematurely at the first obstacle.

After the session, the participant will attempt a run of the game’s arcade mode (or closest equivalent) on the default difficulty to see what and how they used the features taught to them. Despite my personal belief that this genre thrives with human competition, CPU fights will be used for an even level of opposition. The arcade run will end once they reach the end or lose a fight. This is less about their success rate (as no default difficulty level is consistent across multiple franchises) but rather about how they cope with the game’s mechanics after the game has attempted to teach them.

All of the games in the sample will use a Sony Dual Shock 3 controller, including those being played on PC. This is to acknowledge the fact that a person attempting the genre for the first time would unlikely have invested in a specialised controller such as a fightpad or arcade stick. The platform being used in the training sessions will be in bold.

My experience with the genre has resulted in me taking many fighting game fundamentals for granted, such as the various joystick motions and the ‘fighting game grammar’ present across most 2D games (discussed later). The main purpose of this practical investigation is to offer an alternate perspective on these games.

As mentioned, the sample is of all of the games played at Evolution 2013 as their inclusion in this prestigious event is evidence that they have been accepted as competitive-worthy games. While EVO 2013 also featured a tournament for ‘Super Smash Brothers Melee’, it is not included in this study on the basis that its inclusion was the result of a charity drive and not the immediate choice of the FGC (Fighting Game Community).

Game: Super Street Fighter IV Arcade Edition 2012 ver. (SFIV)

Developer: Dimps and Capcom

Publisher: Capcom

UK release date: 20 February 2009

Platform: Arcade, PS3, Xbox 360, PC

Game synopsis: The latest in the Street Fighter series and unofficially the flagship game of Evolution with its grand finals being used as the finale of EVO 2013. This is 2012 revision of Super and is set to be replaced by ‘Hyper Street Fighter IV’ in 2014 which was announced at the event. The original 2009 home release was considered by many to mark the start of the ‘fighting game renaissance’. The game relied on lifting elements from SFII in order to achieve mainstream success after the multiple versions of Street Fighter III all failed at becoming a household name (although SFIII 3rd Strike was highly popular in the FGC). Replaced by Ultra Street Fighter IV at EVO 2014.

Player prior experience:

JW: Unowned but experienced

MP: Unplayed but familiar

Teaching mode: Trial mode

Topics covered: Special attacks, combos

Character choice?: All

Story association?: None

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-iEFzZyaSY

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y3t9IPEPYc8

Teaching analysis:

JW: (5th) JW was initially shocked to see the game’s notion for a shoryuken (seen by pressing the back/select button) and still struggled with the motion after realising what it was. He also had trouble with the ‘metsu hadoken’ ultra attack which requires 3 simultaneous button presses. It was finally achieved when the ‘PPP’ button shortcut was discovered. The game provides no explanation on timing or how certain moves require meter, leaving the player with nothing more than a sequence of moves to perform.

MP: (6th) MP at this point had mastered the execution of special attacks. Like JW, problems arose when asked to connect moves with very specific timing. He began to skip missions once it started asking for these very specific combos but because the trials increase with difficulty, no more progress was made. The timing could be solved if the game demonstrated what the combo looks like. Progress resumed when MP changed from Ryu to El Fuerte but ceased again at a similar stage which demanded very specific input timing.

Arcade mode analysis:

JW: Choosing Oni, JW mostly just used normals, only attempting to use special attacks when it occurred to him. These special attacks were used at in-opportune moments such as throwing fireballs at point blank range. At one point he decided to check Oni’s super attack in the start menu command list. Unfortunately his choice of character had a very unorthodox super (LP, LP, LK, HP) that didn’t use any of the motions he had been practicing.

MP: As reflected in the study, MP was much more confident in using special attacks than JW. Playing as ‘glass cannon’ Seth, he was appropriately less aggressive and appeared to consider his opponents actions more carefully and throw when they were blocking. MP also managed some 3-4 hit jab combos although this was by his own confession the result of mindless button bashing. The run ended when facing Zangief’s command throws to which MP wasn’t aware of how to counter.

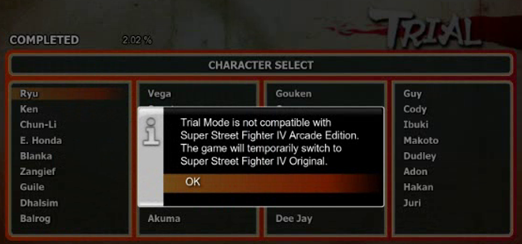

Conclusion: Despite being renowned by critics for being an accessible Street Fighter (by modelling itself on 2 and having less complex mechanics) SFIV falters by having no real tutorial system. No part of the game explains the base systems such as ex attacks and the ultra meter. For a game that is designed to reintroduce casual players into the genre, it seems strange that they would omit a mode which explains the basics as the trial mode seems more about learning specific characters rather than the game in general. The most baffling problem with the trial system is that it teaches possibly redundant combos that may not necessarily work in Arcade Edition:

Game: Tekken Tag Tournament 2 (TTT2)

Developer: Namco Bandai Games

Publisher: Namco Bandai Games

UK release date: 14 September 2012

Platform: Arcade, PS3, Xbox 360, Wii U

Game synopsis: Sequel to the original spin-off released in 1999. This is a non-canonical ‘dream-match’ with a roster that includes almost every character that has ever been playable in the franchise. Unlike most tag games, you only need to KO a single character in order to win a round. The tension of trying to make a weak character tag out has created some welcome tension for matches. The game introduces deeper tag mechanics than the original such as tag crashes and tag assaults. This is TTT2s debut year at EVO and the only fully-3D (z-axis) game at EVO 2013. Also appeared at EVO 2014.

Player prior experience:

JW: Owned

MP: Unplayed but familiar

Teaching modes: Fight lab

Topics covered: Basic movement, high/mid/low attacks, homing attacks, tagging, basic moves

Character choice?: Combot, which the player can customize

Story association?: Philanthropist Lee Chaolan has created ‘Combot’, a robot fighter. Under his supervision, the player must reprogram Combot by learning the basics of fighting. Players can earn currency by playing this mode and use it to customise Combot for use in other modes (apart from online ranked matches from which he is banned).

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CimZuBsn44g

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7jok0HVOOk

Teaching analysis:

JW: (1st) Owning TTT2, JW had little trouble with the tasks presented. After the commitment time expired, he chose to continue playing a bit longer. He also pointed out to me that despite having played the game many times, this was his first exposure to the Fight Lab mode.

MP: (8th) MP struggled with the inputs for motion, having trouble distinguishing between ‘tap’ and ‘hold’. He appeared frustrated with the ‘boss battles’ which are attempts at turning each step into a mini game that assesses whether or not the lessons have been learnt correctly. While having a ‘fail state’ was good to make sure the systems were understood before advancing, it was clearly irritating for MP to fail. In the section in which the player must use specific attacks, MP repeatedly used a kick which didn’t count as the ‘high’ requested by the game.

Arcade mode analysis:

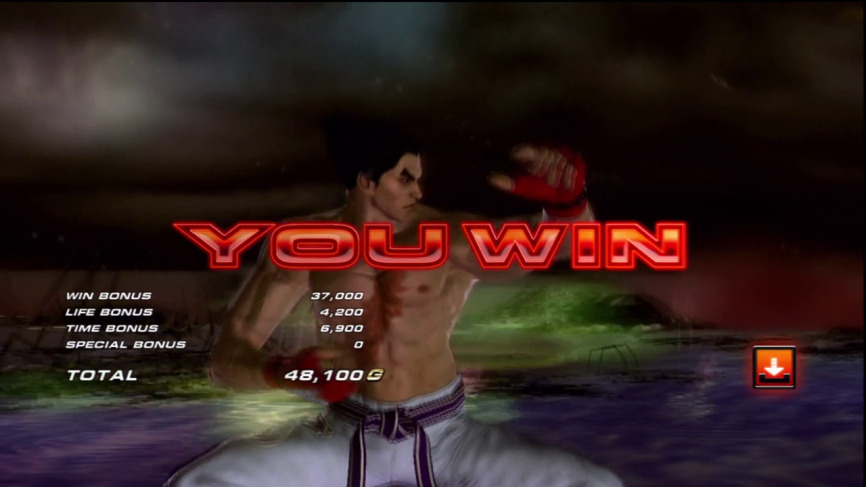

JW: Interestingly JW decided to ignore the game’s tag feature and play the game with a solo character. By doing this I couldn’t assess his awareness of TTT2’s tag features but I couldn’t disallow him from choosing this valid option either. Choosing his favourite character Kazuya, JW completed the arcade mode with ease. He regularly used signature moves such as the ‘electric wind god fist’ but never used any actual juggle combos, playing the game more like Tekken 2 or 3 than its later iterations. Clearly a fan of the game, he managed to complete the arcade mode without a single loss, the only occurrence of this happening in the study.

MP: MP chooses animal characters Roger and Alex at near random. Clearly just button bashing with these wholly-foreign characters, MP loses the first fight, ending his attempt at the arcade mode almost immediately. Having never reached any information on tagging, MP is unaware that a single KO means failure and isn’t even aware of which button is used for the action. I also attribute this first level failure due to a level of fatigue and lack of motivation as this was his final game to play.

Conclusion: Fight Lab was a deliberate effort by Namco to teach players the fundamentals of the game as a method of introducing newcomers in a way that still felt like a game rather than a series of instructions.

“In Fight Lab, we’ve created a series of mini-games that help improve players’ skills without it feeling like a tutorial,” (Tekken lead designer Harada, 2012)

While as an experienced player of this game, JW enjoyed the tasks, MP was frustrated by trying to understand their relevancy in an actual fight. Indeed while it does one of the best attempts at explaining concepts at their most base level (such as high, mid and low attacks) it does arguably dwell on them too long for some player’s patience. Fight lab is a long experience, more comparable to a story mode than a simple tutorial. While a decent way of making learning the game ‘fun’ it is perhaps too much of a time investment for players that just want to get into some actual fights.

Game: Mortal Kombat (AKA Mortal Kombat 9, MK9)

Developer: NetherRealm Studios

Publisher: Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment

UK release date: 21 April 2011

Platform: Xbox 360, PS3, PS Vita, PC

Game synopsis: The first game in the highly popular series to be taken ‘seriously’ by the FGC. Unlike the other MK games of the past decade (‘Deadly Alliance’, ‘Deception’ and ‘Armageddon’), MK9 was consciously developed with competitive play in mind. This was achieved through serious attempts at character balancing, a return to a 2D perspective and the addition of a meter which governs EX attacks, combo breakers and the ultra combo-like x-ray move.

Player prior experience:

JW: Unplayed but familiar

MP: Unplayed but familiar

Teaching modes: Tutorial

Topics covered: Basic movement, normals, special moves, ex attacks, x-rays, tag combos

Character choice?: Johnny Cage and Sonya

Story association?: None

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e1xoVDMA_XA

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=07FwB_imdmo

Teaching analysis:

JW: (7th) Being a very straightforward tutorial, progression was relatively seamless. JW told me that he much preferred MK9s method of commands over those by Capcom (down, forward rather than QCF) and this was apparent from his improvement in being able to execute specials. He did get stuck on EX moves as he quickly skipped through the initial descriptions. He got stuck when asked to execute the numerous types of tag combos to proceed.

MP: (1st) This was a similar experience as JW which also ended at the test which required multiple specific types of tag moves. Even when looking at the command list, MP could not determine what he needed to do. The inclusion of tagging in the tutorial is interesting as it isn’t the standard and more of an alternative optional mode. He also had issues with chain combos which require more specific inputs than the other games in the sample (not allowing inputs based on the character animation).

Arcade mode analysis:

JW: Choosing Scorpion, JW mostly used basic attacks only connecting combo links apparently by accident. Not considering the command list, he didn’t perform any special attacks instead preferring to rely on throws.

MP: Playing as Reptile, MP used considerably more special moves but appeared to have issues with defence. This may be the result of MK9 being the only game in the sample that has a block button (as opposed to holding back). Surprisingly, despite being thorough in other areas, the tutorial only casually runs by high and low blocking and never tests the player with it.

Conclusion: MK9 has a fully featured tutorial system that teaches the basics. It does however skip over the basics in a manner that diminishes the importance of the fundamentals. It is also unusual and almost distracting that it dedicates a large part of the tutorial to the systems related to the tag mode which isn’t the core of the game (as it is in SFXT, UMVC3 or TTT2). One positive is that it tests understanding, so players must demonstrate they know how to use an ability before they are allowed to proceed.

Game: Injustice: Gods Among Us (IJ)

Developer: NetherRealm Studios

Publisher: Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment

UK release date: 19 April 2013

Platform: Xbox 360, PS3, Wii U, Xbox One, PS4, PS Vita, PC

Game synopsis: The Mortal Kombat team’s second attempt to make a game with the DC Comics licence after 2008s ‘Mortal Kombat Vs DC Universe’. The game’s main distinction is the ability to interact with the stages, including a button dedicated to ‘interaction’. The game features familiar characters such as Batman and Superman, each of whom have a unique ‘trait’ button. The results of pressing this button are varied including a counter for The Joker, a canned combo for Catwoman and super armour for Lex Luthor. Debut year at EVO, also appeared at EVO 2014.

Player prior experience:

JW: Unplayed but familiar

MP: Owned

Teaching modes: Tutorial

Topics covered: Basic movement, blocking, basic attacks, throws, throw escapes, special attacks, combos, special cancelling, launchers, overhead moves, juggles, trait ability, clash, reversals, tech rolls, wakeup attacks, super attack, intractables

Character choice?: Batman (and Superman briefly)

Story association?: None

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L1y57EaRaRo

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YcRACMMPmbA

Teaching analysis:

JW: (8th) JW had problems with the combo strings as they are handled very differently to Tekken. In that game, button inputs are read once the character has finished the previous attack animation. Injustice is much more literal, requiring the player to input first, then watch the animation be performed. This was also a factor in MK9 but less obvious as the tutorial combos in that game were shorter. He did however find executing special moves in general easier in this than he did with other 2D games in the sample. This is more likely attributed to the commands being down, forward rather than a circular motion much like MK9.

MP: (4th) Having once owned the game, MP had less trouble with the timing of combos and throw escapes. Unlike JW, MP managed to complete the tutorial rather than quit out. The biggest problem was with the need to perform a block escape. Due to the positioning of the characters, MP could not reliably block without backing away from the opponent.

Arcade mode analysis:

JW: Playing as Bane (basing his choice on his fondness of The Dark Knight Rises) JW plays the game in an aggressive and simple manner, relying on normals and throws and apparently only using combos by accident. Likely due to his experience with Tekken, it does not occur to him to look up key special moves in the start menu (which actually shows them first without having to browse the command list). JW does however use a super attack, most likely because it only requires two buttons to activate and isn’t character-specific. Bane uses charge commands, something not covered in the tutorial.

MP: With more experience under his belt, MP chooses The Flash. He plays very similarly to JW, attacking aggressively and without any pre-planned combos (which MP had the opportunity to learn). The main difference is MPs greater awareness of the meter, featuring a more liberal use of supers. His aggression proves to be a hindrance however as he frequently finds himself on the receiving end of somewhat predictable enemy supers.

Conclusion: Injustice is a decent refinement of the tutorial system NetherRealm created for MK9 and undoubtedly one of the best provided by the sample. It explains core concepts including the nature of juggling and the more unique elements such as stage interactions and the clash system. As normal however the game still expects the player to learn much by their own initiative. The juggle combos are fairly easy to execute once one learns the standard combo chains for a character and the game promotes the special moves in the pause menu without making the player scroll through the command list for them. Beyond the base tutorial there are character specific ‘missions’ the player can try.

Game: Persona 4 Arena (P4A)

Developer: Arc System Works

Publisher: Atlus

UK release date: 10 May 2013

Platform: Arcade, PS3, Xbox 360

Game synopsis: Fighting game adaptation of the popular JRPG created by Atlus. Handled by the developers of ‘Guilty Gear’ and ‘Blazblue’, this game is considered a simplified form of them. Featuring an incredibly stylised anime-art style, the game includes many of the tropes from their previous fighters such as a ‘burst’ (combo breaker), instant-kill techniques and the developer’s trademark air-dashes. It also replicates parts of the original RPG with ‘all-out attacks’, ‘awakenings’ and different status effects. Debut year at EVO.

Player prior experience:

JW: Never heard of it

MP: Never heard of it

Teaching modes: Lesson

Topics covered: Movement, basic attacks, persona attacks, combos, easy combos, dodging, all-out attacks, furious actions, throws, throw escapes, supers, super cancels, awakenings, bursts, negative edge, instant block, instant kills

Character choice?: Yu Narukami

Story association?: None

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I_nCCBy4zU8

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YeWv9wIDO7k

Teaching analysis:

JW: (2nd) Initially shocked by the number of lessons in the menu list, JW quickly became at ease once he realised how short each one is. This tutorial system is very specific and leaves little to interpretation. Progress through the lessons was uneventful until JW became stuck on the need to perform a special>super cancel which he couldn’t get the timing of until the 15 minutes expired. An earlier issue was an occurrence in which JW accidentally ‘broke’ the persona he was instructed to block against. This meant that JW had to wait about ten seconds for the enemy persona to regenerate so he could complete the lesson.

MP: (5th) Despite getting stuck on the timing-specific super cancel (a problem MP attributed to physically being unable to input the controller command fast enough) MP managed to complete the tutorial mode before the 15 minutes expired.

Arcade mode analysis:

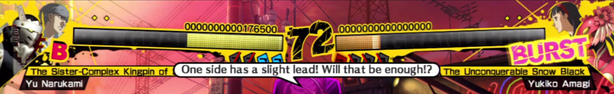

JW: Knowing literally nothing about this game prior to the study, JW elects to use the character he controlled in Lesson mode. He relies on the easy combos (square repeatedly) to perform a high damaging canned combo which ends with a super attack if he has the meter for it. JW also uses some of the ‘two-button techniques’ such as all-out attacks, throws and dodges. As usual for him, JW avoids using many command attacks. JW later told me that he was distracted by the sheer volume of things on screen which was dense with flashy effects and text. The lifebars are very dense with text, some of which is simply story-side fluff:

MP: Briefly glancing through the character select screen, MP gravitates to the highly unusual looking Teddie. MP doesn’t use the easy combos as much as JW and instead mixes up more high and low attacks as well and performing a useful command attack. He also recognises when the enemy is blocking and throws to counter it. MP is also much more active with his movement, jumping into and out of combat.

Conclusion: This is arguably the most ‘complete’ tutorial covering every system in the game aside from actual character-specific combos. The only real criticism available is that it teaches ‘how’ rather than ‘why’. The game does hint at this with brief mentions in text that launchers can be followed up with an air combo but both of my participants only quickly scanned the messages for the actions they were expected to perform. The easy to use canned combo is a reliable way for new players to execute an impressive looking offense with the balance being that it isn’t the optimal combo to use. Fascinatingly, the most inaccessible area of P4A for newcomers is actually the game’s story. Having played the game’s story mode myself, it is obvious that the audience is expected to have played the RPG in order to understand the context for the fighting game.

Game: Street Fighter X Tekken (SFXT)

Developer: Dimps / Capcom

Publisher: Capcom

UK release date: 9 March 2012

Platform: PS3, PS Vita, Xbox 360, PC, iOS

Game synopsis: Capcom’s take on a crossover with Namco’s Tekken franchise, modelled heavily on the Street Fighter IV engine. It was met with initial controversy with its DLC ‘gems’ which created some game-breaking infinite combos and seemed to threaten balance with its ‘pay to win’ scheme despite Capcom’s insistence it was simply a tool to aid newcomers. SFXT is a tag game where, like Tekken Tag 2, one need only KO a single character in order to win. The game utilises a combo system universal to all characters (weak to strong attacks will link) and encourages character synergy. Namco’s ‘Tekken X Street Fighter’ is currently in development.

Player prior experience:

JW: Unplayed but familiar

MP: Unplayed but familiar

Teaching modes: Tutorial

Topics covered: Movement, basic attacks, special attacks, launchers, juggles, charge specials, EX specials, supers, boost combos, combo rush

Character choice?: Ryu and Ken

Story association?: The tutorial is delivered by joke Street Fighter character Dan Hibiki including many story-related jokes and references to the Street Fighter and Tekken franchises.

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYn8nxzIE1Q

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uuqOIlNSysw

Teaching analysis:

JW: (4th) Progress is slow but steady. It is because of this pace that JW only reaches the lesson on super moves before he can be taught about the more advanced tag attacks. Its possible that the tutorial took longer that it should have been needed because of the need to reach several text boxes at the start. As many are just humorous filler, JW eventually found himself scanning the text for the relevant information for the next task.

MP: (7th) It was in MPs tutorial run where one of SFXTs more unique features emerged. After repeatedly failing to perform a throw escape, the game recognised this and offered assistance in the form of the controversial ‘gems’. This is a selectable bonus that can either give a buff under certain circumstances, or make basic actions easier for novice player. In the tutorial run the mission restarted with the ‘throw-escape gem’ active. This makes it so that all throws by the opponent are automatically broken. The balance comes from the fact that the automatic breaking takes some of the valuable super meter. This is a particularly interesting take on balance as a novice player would have less reliance on super meter to string together elaborate tag combos.

Arcade mode analysis:

JW: JW once again opts to use his favourite Tekken character, Kazuya, along with Yoshimitsu. It is important to note that this Capcom-developed game is based on Street Fighter IV and so his skills with TTT2 do not transfer over. Although SFXT has many of the moves JW used heavily in his play of TTT2, they do not use the same controls as SFXT. His play ends up being very similar to SFIV using almost exclusively normal attacks and seemingly forgetting about special moves or looking up the command list.

MP: Despite the existence of gems, MP cannot use any of them as they must be chosen through a special option on the menu. It is worth noting that my purchase of SFXT on Steam included all of the paid DLC gems, suggesting that new players must pay extra to get this helping hand. Arguably an oversight on my part (or the developer’s failure to push the gem customisation feature) MP has to use default sets, none of which provide any actual context for their usage. Gameplay again over-relies on normal pokes and jabs, although MP does successfully use tag supers and tag assaults.

Conclusion: SFXT is a significant improvement over the teaching tools Capcom produced for Marvel Vs Capcom 3 and the different versions of Street Fighter IV. The game does a good job of recognising when a player is stuck, an issue that plagued all of the other tutorials; either slowing them down or just halting progress altogether. A decent tutorial, the more interesting aspect of SFXT that attempts to draw in inexperienced players has to be the gem system. The gems don’t pose too many potential issues for competitive players as they could ban them from tournaments (which they did in EVO 2012). Players can bring three gems into a fight and a power buff would be more useful to an experienced player than a gem that simplifies the commands. The biggest controversy for the beginners is the fact that these ‘assist gems’ cost real world money. This is a double edged sword, as it could bring in extra revenue for Capcom but could just as easily make the new players give up the game altogether. In either case, it certainly is an interesting new approach for the genre much like the free to play model.

Game: Ultimate Marvel Vs Capcom 3 (UMVC3)

Developer: Capcom / Eighting

Publisher: Capcom

UK release date: 18 November 2011

Platform: PS3, Xbox 360, PS Vita

Game synopsis: The latest in Capcom’s long running crossover with Marvel Comics. It is undoubtedly one of the most popular games at EVO due to its spectacle of unpredictable combos, screen-filling super attacks and over-the-top nature spawning many memes in the FGC such as “when’s Marvel”. The game is known for its lengthy combos, requirement to coordinate teams of three characters and surprise comebacks thanks to the game’s ‘X-factor’ buff. UMVC3 is an incredibly fast-paced game with a large (unbalanced) roster of characters many of whom feature unique gimmicks such as Phoenix’s ability to resurrect herself when she has full meter. Also appeared at EVO 2014.

Player prior experience:

JW: Unplayed but familiar

MP: Unplayed but familiar

Teaching modes: Mission

Topics covered: Special moves, combos

Character choice?: All

Story association?: None

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Yb9KlS0s04

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hxdc7wNQ25A

Teaching analysis:

JW: (3rd) Having selected Wolverine, the game requests that they perform a ‘beserker barrage’ with no context or assistance whatsoever. The only way to learn the input at first appears to be to pause the game and check the command list which gives the notation D, DF, F + ‘atk’. However even after learning this the move wouldn’t register. This was fustrating for JW and much time was wasted until he realised that it specified the ‘H’ version of it. To learn what the ‘H’ button was, he had to check the button configuration menu. Despite wishing to stay imparial to the proceedings, I pointed out that he could turn on ‘input display’ so he could tell what buttons were being registed. It was later realised that there was a pause menu option to show the mission input directly. After pushing through some basic combos, JW hit a difficulty wall where he was stuck with a certain mission until the 15 minutes expired and he could quit.

MP: (3rd) Predictably, MP had the same problems with MVC3s limited ‘mission mode’ which is the closest thing the game has to a tutorial. The most obvious difficulty was ‘cancelling moves’ which requires not only a specific set of inputs but also highly specific timing on their entry. Again, an actual demonstration of the combo would help immensely. Once stuck, MP changed character from Ironman to Magneto but got stuck at a similarly demanding stage.

Arcade mode analysis:

JW: It was very obvious how ill-equipped the mission mode left JW for his arcade run. Core concepts had been used (such as basic combos) but they weren’t explained in detail or reinforced in any meaningful way. While he did perform a standard four-hit launcher combo (L,M,H,S), in the mission mode it just seemed like a series random buttons to press in order rather than part of the game’s systems for dealing significant damage.

MP: Picking a combination of Spider-Man, Wolverine and M.O.D.O.K I am reminded that this game doesn’t just require detailed knowledge of a single character in order to succeed but rather three. In addition to this, the team of characters must be able to play off each other to maximize combo potential. This game is less about finding a ‘main’ but rather a ‘main team’. Not fully understanding how the game works, MPs playthrough also devolved into a series of basic jabs and jumping.

Conclusion: Even if one accepts that this is a mode solely for players that already know the basics and want to learn some useful character-specific combos, the mission mode is very poorly designed. Beyond never explaining the core controls or combo system (such as the fact that moves can link from weak to strong) the game hides the actual inputs for moves behind a menu. The only information present on screen are the actual move names which are only helpful once a player is already highly familiar with a particular character. Like SFIV, MVC3 was a simplification of the previous games which makes Capcom’s omission of a standard tutorial particularly odd from a design perspective. Much of this game’s appeal is the ability to create original combos through various means but exposure to this only seems possible through experience with other human opponents (or higher difficulty AI).

Game: The King of Fighters XIII (KOFXIII)

Developer: SNK Playmore

Publisher: Rising Star Games

UK release date: 25 November 2011

Platform: Arcade, PS3, Xbox 360, PC

Game synopsis: Despite some experimentation in the past with tag mechanics and assist characters, KOFXIII adheres to the original turn-based team of three structure. After KOFXII was met with a mixed reception (the game was more focused on introducing a new sprite style than refine the mechanics) this new game is considered one of the most exciting to watch at EVO having become a sleeper-hit of sorts in 2012. The game has two meters- a standard super meter and another dedicated to cancelling moves for extended combos. The characters are very manoeuvrable capable of different types of jumps and evasive rolls making KOF a very defensive game. The need to select three characters results in some varied character match-ups, a welcome feature for spectators. Also appeared at EVO 2014.

Player prior experience:

JW: Unplayed but familiar

MP: Never heard of it

Teaching modes: Tutorial (base system + gauge system)

Topics covered: Basic movement, jump types, basic attacks, special attacks, EX special attacks, guard cancels,

Character choice?: Kyo

Story association?: The tutorial is presented by story NPC Rose Bernstein, host of the KOF tournament.

YouTube URLs:

JW: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kt5H1tVt-Wk

MP: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SCb6Nfa4lJo

Teaching analysis:

JW: (6th) The tutorial had a gradual pacing to it that was very good at easing the player in, even dividing basic attacks from more complex meter use. The game was fairly good at explaining its inputs in plain English such as explaining a hyperhop as “down briefly followed by up briefly”. While still not perfect it does take the usually overlooked timing into account. Another aspect worthy of praise was the ‘explanation’ option present when viewing the command menu which spells out the game’s notion system.

MP: (2nd) The only problem that arose was MP being unable to perform a guard cancel (forwards, triangle and circle simultaneously while blocking). MP was unsure how to input forwards while he had to hold back to block. Despite wishing to stay neutral, I pointed out that he can block while crouching (which keeps him stationary) to ease his frustration. Despite providing an explanation of the notation system, MP eventually hit a far too complex combo string for him to continue.

Arcade mode analysis:

JW: One unique aspect to KOFXIII is its inclusion of ‘target actions’ which appear in single player modes. These give the player a task (such as ‘perform 3 jumps’) and gives them cancel meter if they can accomplish it. It seems like a useful way to make the player experiment with the mechanics and familiarise themselves with the game’s terminology but at the same time it seems counter-intuitive to make a player jump repeatedly in the middle of a fight just for the sake of it. Much like all 2D games in the sample, JW didn’t bother looking up any of the special commands in the pause menu (a constant feature of all the games in the sample) which may be a response to only having a familiarly with Tekken which has no separate category for special moves.

MP: MP plays more conservatively than JW, being more conscious of defence than just running in to perform punches, kicks and throws. MP plays KOF similarly to SFIV with decent attempts at spacing and pokes. If I were to recommend a game for him, it would be either this or SFIV as they are more about careful counter attacks rather than the 100+ combo strings of MVC3. Progress in KOFXIII is decent until MP is defeated by sub-boss Billy Kane which marks a notable increase in AI difficulty.

Conclusion: While I am familiar with this franchise’s history and lineage and can appreciate it for them, I can imagine that in the eyes of my two participants this game appears relatively mundane, lacking the style of P4A, the familiar characters of IJ/MVC3 or the bloody violence of MK9. While KOFXIII does have a decent tutorial, it still expects the player to learn a great deal on their own, especially in regards to move cancelling. One must also remember that the tutorial is limited to main protagonist Kyo Kusanagi and it is up to the player to try and learn the intricacies of the other characters. Like Injustice, there are also character-specific trials beyond the tutorial.

Analysis conclusion:

While still not perfect, it is clear that more and more games are creating decent tutorial systems. This is especially evident in the difference between SFIV and SFXT which were made by the same team at Capcom. In game-tutorials aren’t a new feature for the genre with most SNK games on the Neo Geo featuring a ‘how to play’ demonstration at the start of a new game.

The King of Fighters 2000 (Neo Geo), SNK

While some games do teach the basic controls and abilities of the characters, they very rarely instruct the player on why certain moves should be used beyond a casual mention that throws should be used against blocking opponents. If a player wants to play a game at a higher level, external research is required. Thankfully this is readily supplied by the FGC in the form of FAQs and guides.

Perhaps the more interesting design choices are the ‘shortcuts’ games like SFXT and MVC3 use to bypass learning altogether. MVC3 has a ‘beginner mode’ that devolves all of the combos and special moves into simplified button inputs and SFXT has a DLC gem that achieves the same effect. Both hamstring the player by making some special attacks inaccessible in MVC3 and using up gem slots in SFXT (which other obvious downside being that it costs extra money). These shortcuts seem to make the controls adhere to more modern design sensibilities but don’t really help a player as they are no longer exposed to the unorthodox controls they ideally need to master to play the game as intended.

From this study, I believe that most fighting games, including those that include more comprehensive tutorials, overestimate the player’s familiarity with the genre as a whole. They should perhaps also explain the pros and cons of certain manoeuvres when they are taught in the context of playing against another person.

If I were to do this practical study again, I would make it the crux of my fighting game investigation and include a larger sample. I would also like to devise a quantitive measurement of their skill (such as a win/loss record online).

The Biggest Hurdle: Controls

The investigation made it clear to me that the controls are the biggest hurdle to players to understand. This is due to their almost stubborn following of the past. Despite the fact that most of the games in the sample do not have an arcade counterpart, they still insist on using nothing more than 8 directions and 4/6 buttons. As described in part one, developers would be unwilling (and probably foolish) to alienate the existing consumers of the genre. The FGC are fixated on the values of the arcade even though modern controllers have more than enough buttons to dedicate to special moves without the need to combine fewer buttons to achieve the same effect. A notable popular exception is Nintendo’s ‘Super Smash Bros’ franchise. The original released in 1999 was clearly designed around the N64 controller featuring analogue movement and only two main attack buttons. Special attacks were achieved by pressing a direction with the ‘special’ button. This clearly made it accessible for many players. The FGC and its traditional game values still view the franchise with suspicion and frequently argue that it isn’t a fighting game at all.

The standards of fighting game controls are comparatively abstract compared to most other genres. A first person shooter lets the player move in a three dimensional space to point a gun and pull the controller trigger to fire. Even on a joypad a driving game is a familiar recreation of the act of driving a car. Even an RTS game pulls from the interface controls any computer user will be familiar with from their operating system (labelled buttons, drag to select multiple files/units, etc).

Fighting games as defined by this study take place from a 2D side perspective. Even those with three dimensional movement like ‘Tekken’ and ‘Soul Calibur’ place the camera in a side perspective and the game controls relative to the 2D plane. Control over a martial artist is considerably less obvious than recreating the act of shooting a gun or even running around in a third person action game.

“In a FPS game, players can fully identify with game characters represented only by weapons or hands, shown as virtual prostheses that reach into the game environment (Grimshaw, 2008). This means that players virtually turn into game characters in a FPS game, since they feel like they are acting directly in the virtual game world. In addition to the FPS perspective, the consequence and meaning of player action within the environment and its impact on gameplay greatly influence the feeling of immersion (Nacke & Lindley, 2010)

The most unusual inputs are usually for special attacks which were designed to maximize the number of attacks with a limited number of buttons.

These complex inputs are the reserve of the vital ‘special attacks’. Surman stresses that this is a fundamental part of the pleasure of fighting games for two reasons:

“They are characterized by two pleasure registers; first in viewing the spectacular representation of the special move (hurling a fireball, belching a ball of flame) and secondly in a sense of reward or gratification – a confirmation of the player’s successful mastery of the videogame control inputs.” (Surman, 2007)

I believe that the properties of these special moves (such as Ryu’s signature anti-air shoryuken) should be stressed more in tutorials and even go as far to instruct the player on the actual physicality of how to input them on a controller.

Genre Uniformity and Game Grammar

Based on my experience I believe that all of the games in this genre have a common ‘game grammar’. Recognising this can greatly benefit a player. As mentioned in the methodology, skills learnt in one game can transfer over to another and it is my belief that making the effort to understand one fighting game can make all fighting games more accessible. I shall now discuss some of these shared characteristics in relation to how they may help a beginner. Once mastered, the quarter circle motions could become simple ‘muscle memory’-

“For game analysis, this suggests the possibility of closely studying the relations between input device design, and player actions. It would allow, for instance, the study of how in some fighting games, one mechanic is not triggered by one button, but by a combination of input processes. Thus, it could be argued from a formal perspective that mastery in fighting games comes from the mapping (Norman, 2002, pp. 17, 75-77), of one mechanic with a set of input procedures, which leads to both psychological and physiological mappings - how the "body" of a player learns to forget about the remembering the illogical sequence of inputs, and maps one mechanic to one set of coordinated, not necessarily conscious moves.” - (Sicart, 2008)

Some common 2D command inputs include:

Quarter Circle Forward or Backwards + Attack Button

Back, Forwards + Attack Button

Back, Back or Forward, Forward + Attack Button

360 Motion + Attack Button

Simultaneous button presses

For a player with no attachment to arcades or sticks, these controls are unusual and demanding. (Surman, 2007) places great emphasis on these special moves stating the successful execution is how they excite the player (when combined with visual effects). Mastering a special move has as a similar sensation to mastering a martial art technique in real life.

As polygonal games don’t have to rely on sprites they can have far more extensive command lists. Every character in Tekken has over 100 different attacks. As such, the value of some ‘special’ moves is diminished. In these games some characters may have a number of more useful signature moves as demonstrated in JWs run of TTT2. While not given any special priority in the game, players may consider Devil Jin’s unique laser attacks or Paul’s infamous Phoenix Smasher to be ‘special’ moves as they have almost trademark usage by these characters. Some of these attacks may be shared by multiple characters for storyline purposes such as the members of the Mishima family having some shared uppercuts and axe kicks.

Each button on the controller should ideally have a scheme that makes sense. This can result in Sicart’s psychological support which aids executing input commands. This makes memorising moves significantly easier and cuts down on any abstractions when learning commands resulting in what some may call ‘muscle memory’. These control schemes are largely based how many buttons the game utilizes, the original ‘Street Fighter’ being considered extreme in the late 80s for requiring 6 buttons (as a replacement for the pressure-sensitive punch pads which were prone to malfunction). Some franchise-based controls schemes include-

Street Fighter (6 buttons)

Light Punch, Medium Punch, Strong Punch, Light Kick, Medium Kick, Strong Kick

Tekken (4 buttons)

Left Arm, Right Arm, Left Leg, Right Leg

Virtua Fighter (3 buttons)

Guard, Punch, Kick

Mortal Kombat (5 buttons)

High Punch, Low Punch, Block, High Kick, Low Kick

Injustice: Gods Among Us (6 buttons)

Light, Medium, Heavy, Trait, Interaction

Marvel Vs Capcom 3 (6 buttons)

Light, Medium, Heavy, Launcher, Tag 1, Tag 2

Mortal Kombat Deadly Alliance (6 buttons)

Punch 1, Punch 2, Kick 1, Kick 2, Style Change, Special

Guilty Gear X (6 buttons)

Punch, Kick, Slash, H-Slash, Dust, Respect

A MadCatz produced arcade-stick

These button labels make it easy to understand what the responses will be like.Power strength and punch/kick combinations have been reoccurring ever since ‘Street Fighter 1’. Franchises rarely diverge from their set control schemes even as they evolve. At most a franchise may introduce another button for a new ability such as ‘Tekken Tag Tournament’s’ fifth ‘Tag’ button or ‘Mortal Kombat 3’s’ sixth ‘Run’ button. Constants when designing controls help the player predict what will happen with each press and create a subconscious understanding of the control lists. A player that recalls a move where a Tekken character dashes forward and then kicks with the right leg will probably be able to guess that the command input is forward, forward, circle on a PlayStation replicating the movement forward followed by the right kick button. The ambiguous ‘1 and 2’ punch/kick types in ‘Mortal Kombat Deadly Alliance’ (as well as all other sixth generation Mortal Kombat games) make it less clear what the result of each button press will be and so relies on the player’s rote memorisation of the commands. Very few tutorials actually state what these buttons are outside of a control configuration screen.

Beyond the basic attacks, each fighting game has its own systems of offense and defence. These apply to all the characters in the game. Games may have a unique combo system such as ‘Darkstalker’s’ zig-zag system which is universal and applies to the entire cast. In this franchise, all normals will combo when used in acceding strength. As soon as this rule is learnt, it allows the player to perform basic combos with any character.

Growing experience alongside a franchise

Besides adding new characters and minor tweaks for balance, evolving and developing systems is main way a fighting game franchise can grow. Using the main releases of the Tekken franchise as an example-

Tekken (1994/1995)- base game, establishes characters and limb-based combat system

Tekken 2 (1996)- gameplay made notably faster, adds back throws

Tekken 3 (1998)- adds side-step ability, jumps are more realistic, adds side throws

Tekken Tag Tournament (1999)- direct upgrade to Tekken 3 adding tag mechanic

Tekken 4 (2001)- experimental entry in the series; adds walls, uneven floors and positional swaps

Tekken 5 (2005)- removes the less successful additions from Tekken 4 (uneven floors, positional swaps) but keeps walls which are made less exploitable for high damaging combos

Tekken 6 (2008/2009)- adds bound system to extend juggle combos, rage system, stage transitions

Tekken Tag Tournament 2 (2011/2012)- turns Tag into a spin-off franchise, adds tag crash, tag assault and tag throws as well as a solo option, Tekken 6's rage and stage systems are adapted for team-based gameplay

This is not including ‘quantative’ improvements such as more characters and move moves. For a learning curve Tekken has built upon its foundations since its inception in 1994. Its arguable that to get the best learning experience for Tekken Tag Tournament 2, a player should play through each entry in the series. The first game has the basics and each new entry gradually expands the complexity of the controls, combos and defence systems. Even with the changes since Tekken 1 however, Tekken Tag Tournament 2 is still recognisably Tekken because it still adheres to the original limb-based control scheme thus defining the franchise. It is interesting to note that JW never utilized the bound combos introduced in Tekken 6- suggesting a point where the game becomes too complex for certain fans.

Likewise, moving away from these core systems are necessary to provide a new franchise with a USP. According to lead designer Ed Boon, when creating Injustice, Netherrealm Studios deliberately avoided including a block button in order to differentiate it from their existing ‘Mortal Kombat’ franchise.

“So, certain things—fundamental things—like the attack buttons and what they do, adding the power button that's unique to each character, holding away to block, getting rid of round 1/round 2 all of these fundamental, staple things in Mortal Kombat. We wanted to establish a whole new feel for this game.” - (Boon, 2013)

This combined with the stage interaction helped establish Injustice as a new IP (albeit based on existing comic books). This ‘franchise-building’ means that the learning curve of a game can spread over a decade’s worth of games publishing.

The Demands of Online Multiplayer

Fighting games have ‘lagged behind’ so to speak compared to many other genres in their adoption of online multiplayer. One reason is the fact that these are (often) Japanese-developed games for consoles, a country with less need for online competition as arcades are still plentiful. A second likely reason as to why fighting games were slower to include online than other contemporary genres is the greater need for a fast connection. While lag is certainly an issue in ‘Counter-Strike’ and ‘Unreal Tournament’, fighting games have a far lower tolerance for input delay on moves. This is because a single frame can decide a match and lag on the controls can upset the specific timing needed for combos (Goren, 2013). To bring in online multiplayer, the world had to catch up with its adoption of broadband internet speeds. Some critics complained that in 2005 ‘Soul Calibur III’ for the PS2 didn’t include online play, Namco countering that average global internet speeds and console infrastructures simply were not reliable enough at the time.

“Well, we're trying to make a product towards a global audience. The online infrastructure is not developed in many regions so the online aspect would be unplayable for many gamers. So we decided to not go online this time, instead concentrating on upgrading the content and characters to provide a game that can be played by everyone.” - (Yotoriyama, 2005)

While previously Tekken 3 would have satisfied casual fans with CPU matches, the option to play against other people on demand has introduced this wholly different experience to many who would have otherwise had no human competition. Fighting games are designed to accommodate two human players and the experience of fighting against AI loses some of the major appeal of the genre. Essentially, by including online play, more people were introduced to the competitive value of human competition- including the simple ‘mind-game’. The human element can radically change the game experience. For example, people are often impulsive, so one may predict a novice opponent that currently has low life to simply throw out a meter-consuming super combo out of sheer desperation. A player that recognises this desperation can bait it out and counter for the win much like an effective game of poker. Compared to experiences like this, a single player match is nothing more than responding to the random actions of a computer. Nowadays the greatest consideration with fighting games isn’t whether or not they’ll include online play but rather how reliable the netcode will be, the PC ports of Mortal Kombat 9 and The King of Fighters XIII recently getting attention for theirs (Sanchez, 2013) (Dias, 2013). Decent netcode is another consideration for the multiplayer-focused FGC.

One of the benefits, coinciding with Surman’s reward spectacle is the feeling of accomplishment once a player manages to master a difficult system or defeat a skilled opponent. To distil a command into a single button press could have ramifications that alienate the FGC- the avid consumers of games you’re trying to sell. Players like known entities and developers trying to invest in a new game may fear taking that risk. Super Smash Bros is one of the few games that gambled with a new take and succeeded (no doubt partially thanks to its all-star cast of characters). The job of a modern fighting game developer perhaps isn’t to redefine these traditional mechanics but rather to teach the existing ones (archaic as they may be) to a new market where ‘Call of Duty’ and ‘Grand Theft Auto’ rule supreme.

Genre divergence

This notion of control grammar obviously doesn’t mean all fighting games are universal in their rules and systems. Each game also has its own terminology with different words often meaning the exact same thing. Street Fighter’s ‘Perfect’ is identical to ‘Mortal Kombat’s’ ‘Flawless Victory’ or ‘Virtua Fighter’s’ ‘Excellent’. This jargon can also change by region. The Japanese version of ‘Street Fighter III’ refers to blocking as ‘guarding’ and parrying as ‘blocking’. These ambiguous terms could potentially cause confusion. Some of the Japanese takes on English words are also somewhat confusing such as ‘just defence’ meaning pressing block ‘just’ in time. A more subtle difference between games is how they handle input. A game like Tekken reads input after the animation for each part of a combo is complete. Injustice on the other hand reads all of the inputs before the linear animation begins. In my study the experienced Tekken player had trouble executing a very simple Injustice combo because of the dissonance of what (Swink, 2009) refers to as ‘ADSR’ (Attack, Delay, Sustain, Release). Injustice feels very ‘fluid’ whereas the Tekken inputs feel more responsive. Both types of game feel successfully replicate the feel of a martial arts fight despite doing so in different ways. The actual input reading was not acknowledged by the tutorials of either TTT2 or IJ.

One must consider the scale of skill levels for new players to go against. Sirlin suggests new players should gradually pace themselves against similar players. He also claims that playing against experts can also provide a feedback mechanism for teaching the player what not to do. In this scenario, incorrect moves will be punished appropriately by an expert opponent. The novice player will also be exposed to combos which may expand their understanding of the game. The problem with this is that it may leave a player in a state of helplessness akin to a game being frustratingly difficult.

External research for the player

Inevitably when starting a new game failure will sometimes occur. What’s important is that a player can recognise where they made a mistake and learn from it. This is best taken from experience but the problem is making sure the player can stick with the game through these hardships long enough to eventually learn and improve. Some games such as SSFIV and TTT2 support feedback by letting players save replays and even watch others online. This is a reflection of perhaps the FGCs biggest role- teaching. It has been made clear that the FGC enjoy deconstructing mechanics in order to become better at the game. This has resulted in the creation of countless guides and teaching material that new players can use to improve play. One of the best ways to show off you know a game exceedingly well is to teach others. Sirlin stresses that all competitive games are coupled with a feeling of awkwardness when first starting. A mentor can be highly beneficial. One could state that the countless community made tutorials and guides could provide this mentoring role. These exist on sites such as Shoryuken.com and EventHubs.

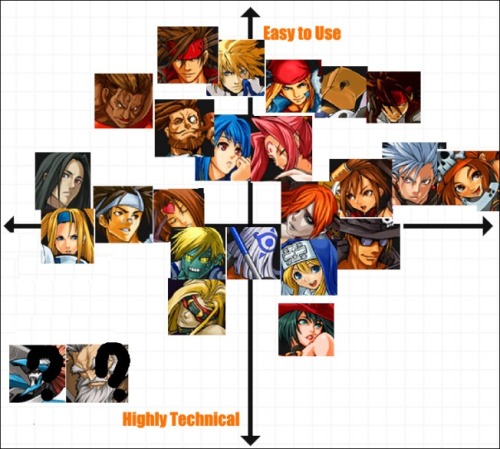

An ‘ease of use’ tier list for ‘Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Reload’ created by player ‘Nerdjosh’ as found on EventHubs (Jodoin, 2013)

If fighting games have lacklustre teaching features, it’s likely because developers are aware the fighting game community will fill the gap. This is still a problem for players that don’t have the initiative to look them up.

Conclusion

It seems that to keep the market already invested in the genre, fighting games are incredibly reliant on traditional features and those that attempt to take advantage of modern controllers are met with distrust. It is these mismatched values that are the biggest divider between new players and those with experience. The original ‘Super Smash Bros’ was clearly designed around the N64 controller. Amongst the games that can easily be labelled as fighters (the dual lifebar interface is uniform) there exist a handful of unconventional fighting games such as ‘Super Smash Brothers’ and ‘Bushido Blade’. It seems that the only factor that separates these games from the traditional-fare is that they were designed with a willingness to step away from the genre’s arcade heritage. Other than Smash Brothers (likely due to its all-star cast of characters), none of these games ever became major hits thus setting a willingness to appeal to the traditional views of the FGC. With this being the scenario the only way to adapt is to make new players understand these arcade values.

Fighting games remain relatively unchanged from their inception and given that one of the most successful games (SFIV) models itself on the very original genre-definer, it is clear that people like known-quantities with their favourite genres. This isn’t to say joystick motions are illogical features added simply for tradition’s sake as Surman argued that overcoming the learning curve is a major reason why these skill-based games are fulfilling from managing to defeat a high-ranked opponent to ‘hit-confirming’ your very first super combo.

The FGC enjoy deconstructing the games and continuously bettering themselves. Essentially this means that the players enjoy continuously learning (including through FGC guides and videos). According to Chris Crawford in 1984, learning from video game experiences is one of the activity’s key appealing factors-

"I claim that the fundamental motivation for all game-playing is to learn. This is the original motivation for game-playing, and surely retains much of its importance...I must qualify my claim that the fundamental motivation for all game-play is to learn. First, the educational motivation may not be conscious. Indeed, it may well take the form of a vague predilection to play games. The fact that this motivation may be unconscious does not lessen its import; indeed, the fact would lend credence to the assertion that learning is a truly fundamental motivation." (Crawford, 1984)

I have discovered that by appealing to the hardcore players (which is already a guaranteed market for the genre) fighting game developers can rely on them to bring in newcomers. Exposure on tournament streams can help attract new players who enjoy the spectacle and these players who now invest in a new game can then refer to the FGC made content to keep them playing and possibly even become brand-loyal. This explains why a lot of the core systems are not explained to the player; they are best learnt through experience. In an era where hardcore gamers protest that modern games are far too eager to hold player’s hands through the game experience (Bandah, 2010) fighting games differ in that they only lay out the absolute essentials (and sometimes not even that) and just leave players to learn by themselves. I believe this is main driving force for those passionate about fighting games. With no world to explore or complex mystery plot to uncover, the point of fighting games is to endlessly improve oneself. This has been reinforced by the rise of online multiplayer which has compensated for death of human competition in arcades. This motivation to better one’s self, reinforced through reward mechanisms as simple as a win/loss record is the perfect motivator for a set of games based on martial arts.

Fighting games have a simple to understand rule set for mass-appeal achieved through the straightforwardness of combat and the system level depth that allows the experienced players to experiment and find new avenues of enjoyment with the endless goal of bettering oneself. The development of internet streams has helped competitive play find an audience and developers are willing to use them to show off their latest products. By fulfilling the needs of this high-level audience, they can fill the gap to help introduce new consumers. Fighting game players are very much like the Street Fighter character Ryu- endlessly seeking the next challenge and willing to help beginners on their own journey of fighting self-discovery. For developers, perhaps the most radical and effective way to teach players in-game is to integrate the teaching content fans enjoy producing. With the advent of the PS4s 'share' button and the overall integration of social networks into games, this seems like a logical step to elevate fighting games to more mainstream success.

Street Fighter II (arcade) Ryu ending

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like