Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Metrics can rule you -- but should they? The Workshop Entertainment's new design director and Free Realms veteran Laralyn McWilliams explains how a pivotal moment in her life showed her that overreliance on analytics and friction in social games isn't the answer.

March 11, 2013

Author: by Laralyn McWilliams

Metrics can rule you -- but should they? The Workshop Entertainment's new design director and Free Realms veteran Laralyn McWilliams explains how a pivotal moment in her life showed her that overreliance on analytics and friction in social games isn't the answer.

This article isn't about whether free-to-play games are bad, or social games are evil. For the record, I don't believe either case is true.

This, like life and like metrics, is about evolution. It's about change. It's about picking new behaviors based on the results of previous behaviors. It's about how an understanding of the end game can change the way you play.

It started back in 2006, when I began working on Free Realms. There really weren't many free-to-play games outside of a few upstarts from Asia, so the whole space felt brand new. I was lucky enough to work with a great group of developers at Sony Online Entertainment with an unprecedented amount of experience in online games. As a team, we understood how to make a great MMORPG, but free-to-play was the Wild West.

After launch, we started gathering data and looking at metrics. Although tracking and logging player choices had been an important part of online games for years, we quickly realized we needed better information and we needed it more quickly. This kicked off a frantic but exciting year of post-launch changes, and metrics played the key role.

Metrics gave me information, but they also let players talk to me directly and honestly. This wasn't the "guess, ship, and pray" design process of console games. I wasn't making decisions in a void anymore. With a combination of understanding the game, tracking changes, watching metrics, and listening to players, we made significant improvements to the player experience. We also significantly improved the amount of money we made.

This was free-to-play at its best: happy players, happy development team, happy businesspeople and execs.

I started speaking about metrics at conferences. I talked about what an important design tool they provide, and how they can guide your decisions on a live game (or on the game before launch via usability testing). I shared some metrics about play patterns among casual players, including some findings that were genuinely surprising to the development team.

Then I entered the world of social games.

Development of social games revolves around three core concepts:

Metrics are the basis for all decisions.

Monetization is based on friction.

Metrics and monetization are tuned to optimize the output of whales.

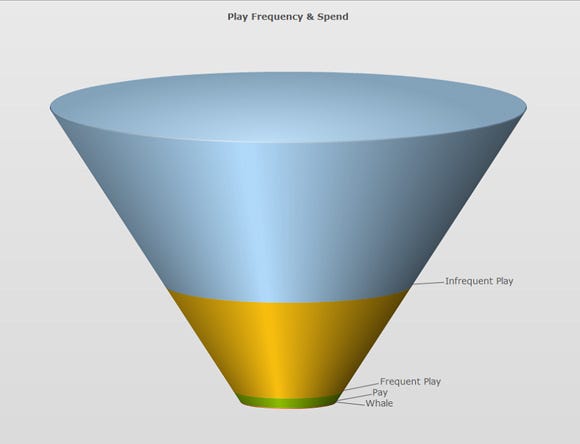

A common way to look at metrics for online games is using a funnel. The typical funnel for user retention and monetization looks like this:

The funnel would have to be scaled larger than your monitor for you to actually see the whales down there at the bottom. That’s the size of a group they represent when viewed in context with the rest of the player base.

For many companies, modern free-to-play design -- especially in social and social/mobile -- focuses on the whales. The game is tuned to please the whales, even though the personality that lends itself to the highest spend in a game is certainly an edge case.

The games aren't just tuned to please the whales, though: they're tuned to squeeze the maximum amount of revenue out of them. Since the monetization is based on friction -- on players paying to bypass elements that stop them from playing, completing, or enjoying aspects of the game -- squeezing the most money out of the whales means continually turning up the friction until you hit the "sweet spot" where they pay regularly.

With the increase in friction comes the increase of players who hit the wall where the session gets so short or the grind gets so tedious that they quit playing. Online games have always had a certain amount of players quitting (called churn). The churn in social games is tremendous because the friction curve quickly gets so steep it curves most players right out of the game.

I'd entered the world of social game design with strong experience in free-to-play design and as an outspoken advocate for metrics as a part of the design process. As I tried to understand social game "best practices," I watched as people made decisions based purely on metrics with no interpretation. I watched as they made changes that increased short-term revenue without regard to the churn consequences of those changes on the larger player base.

I continued to speak at conferences about the importance of metrics as an information source for designers, but when I met someone at a dinner and he said, "Oh, you're the metrics lady," I felt unsettled. I believed in metrics... as a source of information. I'd always said that metrics aren't the answer -- they're one step in discovering the answer. Yet I was seeing metrics used without any attempt to understand the long-term effects of change, or the emotional side of the play experience.

So here I was working on social games, faced with changes required to increase the friction. These changes would get the small group of paying players to pay more but they would also increase the churn across the rest of the player base. I was adding elements to disrupt the play experience -- to knock the player out of the Zen state of connection with our game -- to get him to pay money.

These changes would almost certainly generate more revenue for the company. The company wasn't evil. No one was twirling the ends of his moustache while tying helpless players to the railroad tracks. On the contrary, this company was filled with great people who wanted to make great games. Company growth -- and to some extent company salaries -- depended on the game making money.

As I struggled with these decisions, I watched the industry and I played other social and social/mobile games. I saw players struggling to try to stick to games they genuinely liked. My friends and I were even paying money in some games... just not at the whale level. I watched those games churn us all out. I saw the heart of any online game -- the community of players -- start to flounder as the friction curve increased.

Even as players struggled to stay connected to games that seemed determined to churn them out, I saw companies start to struggle because the "time to churn" was getting shorter. There was more competition in the space and the monetization mechanics in the games were so similar that the games started to feel the same regardless of gameplay mechanics.

Yet the production values were rising, so given the short churn time, even the big companies couldn't put out games quickly enough to churn players into another one of their games.

Friends got laid off. The games didn't change. The companies didn't change. Despite my misgivings and doubts, I didn't change.

Then in late March 2012, I was diagnosed with Stage IV throat cancer.

As you would expect of "the metrics lady," I did a lot of research. At first, it was dumb research because I didn't know any better. I looked at outdated studies or ones based on a different type of cancer. When I started doing better research, I looked at statistical outcomes, survival odds, and other data points. Despite everything I believed, I looked to metrics for answers. And I started to despair because the "answers" weren't promising.

Luckily, I stumbled upon The Median isn't the Message by Stephen Jay Gould, the noted biologist. He'd been diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, and his doctor refused to give him statistics. When he did the research himself, he understood why: the survival odds were terrible, with a median life expectancy of eight months.

When I learned about the eight-month median, my first intellectual reaction was: fine, half the people will live longer; now what are my chances of being in that half. I read for a furious and nervous hour and concluded, with relief: damned good. I possessed every one of the characteristics conferring a probability of longer life: I was young; my disease had been recognized in a relatively early stage; I would receive the nation's best medical treatment; I had the world to live for; I knew how to read the data properly and not despair.

Suddenly I remembered what I already knew: metrics aren't the answer. They're just a source of information and, like all information, they have to be interpreted. Some of that interpretation -- and even the outcome itself -- requires emotional context. Even as a scientist, Gould recognized that "...attitude clearly matters in fighting cancer."

I worked from home during chemotherapy and radiation, but when I was well enough to return to the office, I had changed. The pivotal moment came when a designer asked me if he could add more quests to the game. In this specific game, quests clearly made the game more fun for players. They were motivating and moved the story forward. They reduced -- or in some cases eliminated -- the tedium of grind.

Except paying to skip the grind was a core monetization element. Making a change that was clearly in the player's benefit would be against the benefit of the company. In a premium game, a subscription game, or even a free-to-play game like League of Legends, there would be no question. But in the friction-based monetization world of social games, anything that removes friction also removes monetization. It's not about having a happy player base: it's about having a paying player base.

That moment -- the act of telling the designer not to add quests and soften the grind -- cemented my decision to leave social games.

I still believe in the social game space, and in the players. If anyone needs more great games, it's the huge Facebook audience that so rarely gets them. They've only just begun to see how games can be a meaningful part of your life.

I still believe in the power of metrics as an information source. Metrics are the most direct and honest communication from your players. Even more, I believe in free-to-play games. They force us to get us out of our own heads as developers and design for players rather than for ourselves.

But when it comes to social/mobile game "best practices" and especially friction-based monetization, I believe there's a better way. Players stick with your game because they made an emotional connection. They pay money for your game because that emotional connection is meaningful to them.

There are emotional consequences to basing a game's monetization around steadily increasing friction. Just because players are willing to spend money for something doesn't mean they want to, they like to, or that you haven't just eroded whatever good will they had toward you and your game.

We have models that show huge success, like League of Legends, The Lord of the Rings Online, World of Tanks, and Free Realms. Players will pay to save time, to have unique and visually appealing items, or to customize their experience. They'll pay for fun, they'll pay for coolness, they'll pay for status, and they'll pay for more content in the game.

We don't have to beat them over the head with bricks just so they'll pay us to stop beating them.

Social and social/mobile companies are trapped. Faced with an aggressive marketplace and skyrocketing costs, jobs and even whole companies are at stake. It's hard to justify turning your back on a proven model. To do that, you have to take risks. You have to look beyond data and understand its emotional context. You have to be in the game for the long haul and not for whatever increases tomorrow's profit. You have to see players as your allies instead of test subjects.

You have to stop thinking like GLaDOS and start thinking more like Stephen Jay Gould.

You have to stop thinking like GLaDOS and start thinking more like Stephen Jay Gould.

Our endgame isn't a player who's burned out after paying the maximum we can get out of him for three months. Our endgame is a happy, consistent player who sees the game improving, the community growing, and positive ways for him to spend his money with us over the years. Our endgame is a player who feels like the game community is his home.

Our endgame isn't just about whales. Our endgame is to better the play experience for the whole funnel.

My PET scan in September was all clear. As of now, I'm in remission. I see a specialist once a month to have a scope stuck down my throat so he can see if the cancer's back. I'll have ongoing PET scans and checkups for five years, and after that I'll be called "cured." When I feel a tickle in the back of my throat, like I have the past few weeks, I have trouble sleeping.

I still find myself looking at statistics from time to time. Many say there's a 90 percent cure rate for this specific type of cancer. It's a fairly new area of research, though, and there's a small set of evidence that it may have a much higher than expected rate of metastasis to the lungs. Lung metastasis is tricky business, even if you can have radiation a second time.

But this isn't about survival statistics, and the median isn't the message. This, like life and like metrics, is about evolution. It's about change. It's about picking new behaviors based on the results of previous behaviors.

It's about how an understanding of the endgame can change the way you play.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like