Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A look at games from the dual processes of bringing order and wreaking chaos.

Many, many video games can be seen as the interplay between order and chaos. Some games are all about creating order from a chaotic play field, while others center on wreaking destructive chaos on an ordered world. Players understand this inherently, and I think we even expect it. Many sophisticated games balance the two extremes to create a satisfying experience, and I believe it helps us to consider games from this perspective.

When analyzing gameplay along an order/chaos spectrum, we find that lots of engagement happens when players move the state of the game from one end to the other. It’s often not delightful to stay in one extreme—our sense of agency is stroked when we move between them.

Nature itself tends toward chaos, and it’s part of the human condition to organize it. On the other hand, we become bored with too much structure, and thus feel empowered when we can wreak chaos. Since life is such an interplay between these two states, it’s fitting that so many games hinge on the same concept. Order and chaos are deep-rooted motivations, so they can be channeled into great game dynamics and objectives.

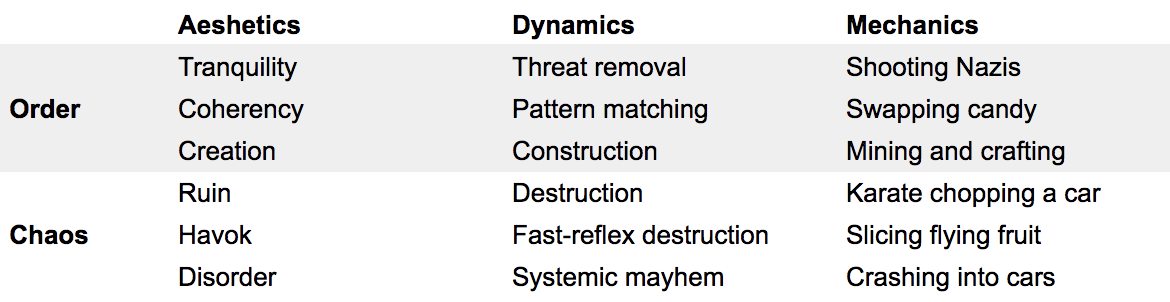

Let’s consider this gameplay spectrum formally. Here is a breakdown of some common examples in MDA form:

MDA structure of examples on order/chaos spectrum

How do order and chaos feel? The aesthetics of this spectrum are calming and safe on one end, but exciting and powerful on the other. Plenty of game ideas are spawned from these aesthetics alone: “I want to build my own civilization from scratch!” “What if you could single-handedly destroy a whole samurai army?!” High-level aesthetics like this are commonly found in intrinsic human motivations (survival, collection, etc.), which explains this tendency in design.

What are some systems that will deliver these experience? The dynamics of chaos-to-order are all about simplification. Players are presented with a jumble of information or a dangerous situation, and are given the opportunity to reduce or streamline. The dynamics of order-to-chaos work in the opposite way: a structured game state is just begging for change, and the player is rewarded for complicating it or even tearing it apart.

These are very recognizable high-level systems, and we all know the building blocks. These are game design’s go-to mechanics: shooting, jumping, combat, mining, crafting, arranging, customization, etc. These are the visceral parts of order and chaos, and they come in many flavors. It’s worth mentioning that a given mechanic can be used to create order or chaos. This suggests that the spectrum is most important at the aesthetic and dynamic levels, whereas player agency and game rules are in service of it.

Games can be seen as voluntary work. It’s the idea that players are signing up to spend energy, thought, and frustration doing something for the fun of it. Real-life work—solving problems, forming plans, putting stuff together—is the stuff of games. From food service to a government desk job, a lot of satisfaction comes from bringing order out of chaos. It’s no wonder that games can harness this well, and we’re reminded how useful it is to base game design in core human motivations.

Games can be seen as playful learning. People are driven from an early age to master concepts, and we feel good doing it. To build a working mental model, we bring order out of chaos. The pattern matching found in match-three games is only a visual distillation of this process—think of pareidolia as the degenerative case. Over millions of years humans have had to pass on hunting and self-defense skills. These became games of controlled chaos for children in every culture, and now we model them in digital form.

Games can be seen as machines for expression. They reduce the friction of the real world, making it easy to do what is normally difficult or frowned-upon. Taboos against violence and destruction can be safely ignored in a game, allowing us to channel our need for chaos. Games can also streamline and bolster the process of creation, letting us reshape or create amazing things from our couch. They can accelerate time or minimize the esoteric, and in playing them we can focus on order and chaos in a secure environment.

While very simple games can get away with only changing order to chaos or vice-versa, larger games harness both directions. Pacing is often strongly coupled with this spectrum. As a game becomes more complex, it’s important to manage the relationships between subsystems. Order and chaos are convenient sides of the same coin, so devs often set them up in feedback loops to keep the play experience predictable and varied.

For example, most first-person shooters usually boil down to sections of high-adrenaline action and low-intensity movement. These correspond to moments of chaos (how efficiently the player can destroy a collection of enemies) in service of order (reducing the local threat level for exploration). Between encounters, players bring order to their experience by picking up loot, deciding weapon loadouts, discussing strategy, and otherwise preparing for chaos. Guns are pure chaos, whereas environmental puzzles are pure order.

Real-time strategy games begin in a state of virgin order. Players carve up the landscape to reshape the terrain and construct buildings. This is done in the service of building units to express their own winning solution. At this point the game tilts toward chaos, as players attack each other with what they’ve created. Players are rewarded for causing disorder among their opponents’ order, and this is a lynchpin of many competitive games. When battles are over, players again return to their bases to incorporate what they’ve learned, rebuild, and readying for more destruction.

Construction-heavy games are inherently expressive, and this often stems from bouncing along the order/chaos spectrum. Mining is the destructive action that enables crafting. Building towers is the creative action that allows us to kill enemy creeps. Persistent user-generated worlds are a pure expression of a player’s unique vision. They survive as inarguable proof of his or her will over chaos.

Order and chaos are heavily influenced by multiplayer dynamics, and even voice communication takes place along the order/chaos spectrum. In team-oriented games, players can speak during engagements and in between them. Successful teams can adapt their tactics as the enemy changes theirs, effectively bringing a behavioral order to the chaos of the battlefield. Good game designs are systems that can be well-understood and predicted in this way, and often feature chaos/order feedback loops.

Games continue to evolve, slowly but surely. Today’s gamer landscape has better technology and a larger audience than it did thirty years ago, but the foundations of great design remain the same. It’s fun and reassuring to see that arcade machines and apps both rely on our inherent hunger for order and chaos. Streaming a speed-run is a relatively new phenomenon, but is it not just a super meta way of displaying order in an otherwise chaotic game?

Devs will continue adding more troops to the battlefield, and they’ll add more options to character creation tools. But while player motivation and alignment is fundamental to the experience, order and chaos will always matter more. Let’s build our games with this in mind.

Check out my blog at medium.com/@johnnelsonrose

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like