Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Neils Clark examines the intimate bond between psychology and play, and how games might tap into the recesses of the ancient human brain in order to reach new levels of immersion.

[In this in-depth analysis, Neils Clark examines the intimate bond between psychology and play, and how games might tap into the recesses of the ancient human brain in order to reach new levels of immersion.]

What many works heretofore miss about immersion is the physiological. Specific senses have specific effects.

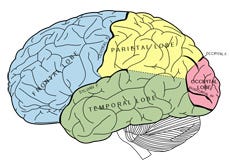

When the reds, greens, and blues of television images careen in through your retinas, and then bang back and forth between your amygdala and your prefrontal cortex, you're having a certain type of experience. When sounds, smells, or even tastes hit varied sensory receptors, you're having other types of experience.

The nature of such input, as well as how it's processed, has an effect on the final product. As games could hypothetically throw together near every other traditional method for presenting media experiences -- from poetry to painting -- it makes sense for developers to understand a great deal about how we sense and perceive them.

Topics like "flow", "theories of fun", culture (online and off), the psychology of identity, operant conditioning, and self-actualization -- more the culture and psychology of media experience -- relate to its physiology as light relates to dark in the Tao; each is fundamentally reliant on the other.

What follows, then, is a mega-abbreviated exploration of how the game experience slaps together a patchwork of elements, in the senses and in the mind, thereby forging something desirable. Something that the brain takes as a convincing-enough pastiche. Something that's still a medium, but which, while in its clutches, the mind might be forgiven for mistaking as real.

Scholars in the field of visual communication, combining theories in fields ranging from evolutionary psychology to neurobiology (Nobel Laureate-types -- not fringe wackos) write that visual media cannot help but be both immediate and convincing.

Much of our visual learning is "prewired by evolution to detect and respond to danger," writes Anne Marie Barry, Associate Professor of Communication at Boston College, saying that while that wiring hasn't changed in millions of years, visual media has.

Much of our visual learning is "prewired by evolution to detect and respond to danger," writes Anne Marie Barry, Associate Professor of Communication at Boston College, saying that while that wiring hasn't changed in millions of years, visual media has.

"For the brain's perceptual system, visual experience in the form of the fine arts, mass media, virtual reality, or even video games is merely a new stimulus we have inherited as part of our brain potential and is processed in the same way." While it doesn't take 18 WIS to know that a television is a television, the implication here is that our visual system taps the forgotten Congo of the brain.

Those ancient, reptilian areas have no physical way of recognizing the difference between everyday experience and the flashing phosphor of a screen. Considering this, Barry suggests that visual media aren't some event. A kid playing violent games, let alone an adult, won't have some Mysterious Black Switch of Menace flipped in their brains. Rather, the brain's visual system files it as one apparently real experience among the many that we might have as we learn and grow.

And yet, visual media may flip a different kind of switch. These theories suggest that convincing visuals draw in a TV watcher, or a gamer, by virtue of simply being visual. Before we can think about our sight, we feel and respond. Optical impulses sent through the "quick and dirty" thalamo-amygdala pathway rush to the amygdala, where they're quickly matched against low-resolution images from this ancient emotional center.

By the time a more fulsome image can be sent down the cortical pathway for conscious, thoughtful awareness, we've already had some type of response. Visual experience that constantly yanks on these visceral puppet-strings, engaging old responses for (for instance) danger or mating, may keep players deeply engaged without their full mental awareness.

Distraction, visual, aural or otherwise, likely also lowers our physical awareness of outside stimuli while gaming. Of course, 'gaming' encompasses a wide variety of designs and experiences. Harry Potter Scene It! is meant to be a wholly different experience than Lego Harry Potter. Paying only physical attention to a board game (not the people, the snacks, or the spilled beer) would be a bit ridiculous. On the flip side, full solitary adhesion to a console game when you're home alone -- that's the ideal.

We want to find an interest-worthy world inside. As we may not even cognitively process inputs that occur while attending especially attractive stimuli, it's possible that some gamers forget near all of what's happened in their apartment during gaming (if it was even processed). They may also forget much of what flew at them in a game (if the game offers too many stimuli to process).

In that sense, though games may be designed as somewhat different than any common experience we're having in everyday life, how we process the gaming experience is physically no different than how our senses process any other experience in day-to-day life.

The human brain has no inborn mechanism separating photorealistic visuals on a screen from the visuals in reality. Sound and vision hold human attention within that frame of experience. In neither case has our fundamental processing changed simply because we've sat down for a little gaming. Physiologically, our Stone Age brains seem helpless but to fall into worlds. Does this imply that in passive media showing realistic scenes, that the barrier for passive immersion is almost zero? What, then, would be the barrier to interactive immersion?

In Rules of Play, game designers Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman argue that much of the games development community wallows in believing an immersive fallacy. They see two major points as fallacious: that the sensual transport is what a person finds pleasurable, and that a media experience can be complete to the point that, "...the frame falls away so that the player truly believes that he or she is part of the imaginary world."

Their argument is based primarily in the philosophy of mind; Salen and Zimmerman draw on theories of metacommunication, remediation, and identity to feel out the reasons that play is too cognitively complex to yield to the immersive fallacy.

Metacommunication was one of the major ideas coined by Gregory Bateson as he explored "the Ecology of Mind". For their purposes, Salen and Zimmerman explain metacommunication as Bateson does, through two dogs play-fighting.

Though they're nipping at each other, there's also this extra communication that says, "We're not fighting; this is fun." Rules of Play takes it deeper, asserting that players can simultaneously know they're only playing, but paradoxically also enter into and believe a media experience. They call it "a double-consciousness in which the player is well aware of the artificiality of the play situation."

"In the case of play," they continue, "we know that metacommunication is always in operation. A teen kissing another teen in Spin the Bottle or a Gran Turismo player driving a virtual race car each understands that their play references other realities... To play a game is to take part in a complex interplay of meaning. But this kind of immersion is quite different from the sensory transport promised by the immersive fallacy."

This paradoxical double-consciousness, always active during play, is further bolstered by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin's remediation, which states that there are always intermedia frames. The theory explores relationships between different kinds of media -- it's also used by Zimmerman and Salen to show how the framing of something like a game interface, inside of an operating system, on a computer monitor, is always providing the user clues to the separation between the medium and reality.

In effect, Rules of Play uses remediation in much the same way as it uses metacommunication -- something which both reminds and yet does not -- leaving play as a complex paradox of the mind.

These theories, along with others illustrating the complexity of paper-and-dice role play, suggest that it's impossible for a player to become the character they play. In other words, Rules of Play appears to argue that a player in, say, Street Fighter, can never fully become Chun-Li, or any of the game's other characters.

While we could certainly deploy metacommunication, remediation, and identity theories in certain play situations, human physiology accurately processes what's put in front of it. Immersion doesn't have to be pleasurable, nor pull us to the other side of the screen, to be effective.

Any non-schizoid gamer, even while roleplaying, will know that they aren't Chun-Li. It's our latent physiology which doesn't make any distinction between real and virtual... if such a distinction were even warranted to begin with.

In ways beyond just the sensual, gamers increasingly take in their pastime like they would any other place. What's more, treating "play" or "virtual" as something separate from "work" or "real", invokes connotations that don't bode well for the burgeoning form.

Anthropologist Thomas Malaby avoids acknowledging the assumptions folks often make for "play" specifically, that it's by nature separable from everyday life, safe, and fun. Though games can be all three, divorcing games from reality keeps their significance at a distance.

In the article Beyond Play, which appeared in the journal Games & Culture, Malaby writes, "This perspective allows some to hold games at arm's length from what matters, from where 'real' things happen, while others cast them as potential utopias promising new transformative possibilities for society, but ultimately just as removed from everyday experience."

Malaby suggests that games have begun to "...approach the texture of everyday experience." Like reality, games have unpredictable outcomes. Like reality, many are always-available. Pepper the game experience with real people, and some games also become working social spheres, another place we go to interact.

Games like Linden Labs' Second Life and Blizzard's World of Warcraft, have become less an Oldenburgian Third Place, more just another place: like the inside of your car, a classroom or even a coffee shop. On a profound level, for some users these technologies have become as rote as writing, using a telephone, or reading a book. "...games," writes Malaby, "by their design, can achieve at best only a relative separation from other parts of experience."

Metacommunication may make sense for certain gaming contexts, perhaps playing Rock Band at a party. Certain gestures or statements, made to other partygoers, add a level of metacommunication to the experience. "Quit tamboreening the microphone on my cat, bro." Remediation may act as a distraction. "You don't have enough points to buy that song? This marketplace stuff is bullshit."

Even in cases where sensual immersion is in constant interruption and the neighbors would kindly like it turned down from 11, the game experience is fluid with reality. There's no need for a co-existing duality that only activates when games are near. We process games as we would any other experience, which is why immersion in games can be so powerful. More than any form heretofore, they look and act like a tangible part of the world; like every form heretofore, they are a tangible part of the world.

Games Literacy (figuring out how the hell you play a set game) likely acts as a better predictor of whether a player is sinking into the murky waters of the gaming double-consciousness. When our senses are first learning to process any new media experience, there's always going to be some learning. Sometimes a game system is restrictively archaic -- or just difficult -- it's perceived as too high a barrier for entry. Raise your hand if you know someone who "only plays Wii."

The icons, gauges, and text that fills the screen in your average World of Warcraft raid interface would probably evoke panic in most normal folks -- probably even in some gamers. World of Goo would similarly strike my grandma as a perniciously perplexing. But as players learn new conventions, just as a driver must learn to automatically process icons that explain speed limits, road warnings, or stopping conventions, play seems to mature into just another experience got through media or reality, as ingrained as the next.

Like the driver who remembers nothing of his trip, so rote is the route, so automatic his reflexes, learning the conventions in new games invites the instantaneity of sensual immersion.

J.R.R. Tolkien's On Fairy-Stories gives an account of literary immersion which is surprisingly (or perhaps unsurprisingly) fluid with contemporary linguistic and neurological theories. "To ask what is the origin of stories," he wrote, "is to ask what is the origin of language and of the mind." Tolkien also pondered a powerful yet then-nonexistent medium, Faërian in nature (yet perhaps suspiciously like gaming), which could "produce Fantasy with a realism and immediacy beyond the compass of any human mechanism."

While vision is the forte of our ancient reptilian brain, it's currently understood that we process grammar and thought in relatively separate areas in the brain. Evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker believes that the mind -- language specifically -- sits in a separate module than processing sensations like sight.

Four modules identified by Pinker are imagery, phonology, grammar, and 'mentalese,' the mind's internal conceptual language. By all accounts it would seem that weaving sound and image from letters requires not only learned literacy from the reader, but art and craft from the writer.

This is why Tolkien supposed that where the odd, spindly letters of literature are able to create the textured, desirable world, what he called a Secondary World, at play is a higher form of immersion he named Enchantment. Our senses in the Primary World fall away.

No dual consciousness, suspension, or other challenge to belief can be tolerated in such Enchantment. Tolkien notes, "The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside. If you are obligated, by kindliness or circumstance, to stay, then disbelief must be suspended..."

Primarily because Tolkien felt stage drama to be a bastard form concerning deep immersion, Enchantment was best left to literature. The sight of a human being dressed as a donkey required a tertiary world -- a world too many. And yet he also claimed perusal of elvish lore pertaining to an odd thing: Faërian Drama.

If you are present at a Faërian drama you yourself are, or think that you are, bodily inside its Secondary World. The experience may be very similar to Dreaming and has (it would seem) sometimes (by men) been confounded with it.

But in Faërian drama you are in a dream that some other mind is weaving, and the knowledge of that alarming fact may slip from your grasp. To experience directly a Secondary World: the potion is too strong, and you give to it Primary Belief, however marvelous the events... Enchantment produces a Secondary World into which both designer and spectator can enter, to the satisfaction of their senses while they are inside; but in its purity it is artistic in desire and purpose.

Even when media taps only some sense processes, be they visual or grammatical in nature, human beings learn to combine disparate elements into reasonable wholes. We experience worlds. Even before we get to the millions of examples out there of what does and doesn't make the stuff of a world desirable, that world must osmose through our eyes, ears, and brain.

When the craft being plied combines as many as a contemporary game, and when we're literate enough in such a form to see, hear, believe, and find what we desire, an immersion unlike any seen in previous mediums becomes possible. "Secondary World" takes on a new meaning, and odd double-consciousnesses seem all the less likely.

Media Experience seems a more accurate, although perhaps imperfect moniker for what we're doing until four AM, while our British model girlfriends walk out the door. As a concept it connects some of the dots that have traditionally separated games from other mediums. Every form through history -- from the Quran to City of Heroes and CNN to the War of the Worlds radio broadcast -- plies certain art and craft to evoke some experience in the mind of the user.

At its best, the purpose of this art and craft is less exiting from the Primary World (though escape can be needful), but rather experiencing a Secondary World. Enjoying a part of our world made by somebody else (or even a group of somebodies).

At its best, the purpose of this art and craft is less exiting from the Primary World (though escape can be needful), but rather experiencing a Secondary World. Enjoying a part of our world made by somebody else (or even a group of somebodies).

This is a point worth highlighting, one made by Tolkien, among many others, on the purpose of such experiences. Though it may seem a tangent (and it could well be one) let Stephen King tell you about his desk -- a desk obtained amidst a long haze of alcoholism and drug addiction, as he discusses in his On Writing.

For years I dreamed of having the sort of massive oak slab that would dominate a room -- no more child's desk in a trailer laundry-closet, no more cramped kneehole in a rented house. In 1981 I got the one I wanted and placed it in the middle of a spacious, skylighted study (it's a converted stable loft at the rear of the house). For six years I sat behind that desk either drunk or wrecked out of my mind, like a ship's captain in charge of a voyage to nowhere.

King's advice on his craft begins with this: "put your desk in the corner, and every time you sit down there to write, remind yourself why it isn't in the middle of the room. Life isn't a support-system for art. It's the other way around."

The poet, arguably the first designer of experience, used all the ordinance that was his craft for evoking certain experience. In plying many tools, he could draw together previously disparate ideas, questioning old notions while creating new ones.

If more powerful immersion lessens the jump, if realistic media experiences shrink the space for using tools of allusion, expression or social comment, then are the goals of Art made more elusive in today's games? How different a beast is Milton's Lycidias from Shadow of the Colossus? What are we evoking? In answering such questions, this medium will continue to both excavate the parts of its soul still-buried in antiquity, simultaneously carving out those that lie beyond the imagination of the past.

This physiological side of immersion is intimately bound to the psychological and cultural reasons for play. In its use of our senses, in its relationship to texture of reality, in exercising our literacy and imagination, it invites us to experience worlds. We've never left the Primary, the Secondary being simply one of its manifestations. And yet we can believe.

[Photos by Felipe Skroski, foshie, used under Creative Commons license.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like