Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra's Christian Nutt speaks to a swath of developers about the "Metroidvania" genre -- what drew them to it, and its potential. Includes new comments from Symphony of the Night's Koji Igarashi, too.

Metroidvania. What image did that word create in your mind? Super Metroid? Castlevania: Symphony of the Night? Or a newer title from an independent developer, like Chasm or Axiom Verge?

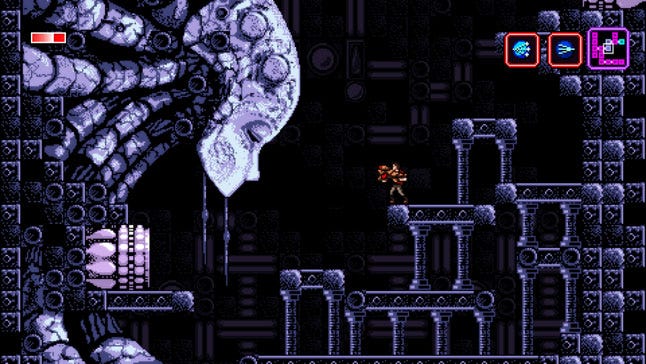

1986's Metroid and its SNES sequel, in particular, are touchstone titles in what has now unquestionably become its own genre. The first in the series introduced many console gamers to the idea of a large, explorable 2D platforming world; in 1994, Super Metroid refined that gameplay immensely while adding deft storytelling. Three years after that, Symphony of the Night expanded this formula in all directions, adding both complexity and depth at every turn.

"First off, I didn't like the state of action games at the time," says Koji "IGA" Igarashi, when asked where 1997's Symphony of the Night came from. "Titles divided into discrete stages were tending to get more and more difficult, leading to the situation where good players quickly finished them and beginners were no longer getting their money's worth. There was also the fact that the people on our team, including myself, really liked The Legend of Zelda, so we wanted to create a game in that style."

In retrospect, it's little surprise that this game launched a genre; it was a clear attempt to break away and create a holistically enjoyable game for a wide audience. The result worked too well to remain unique.

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night

Though retro game fans can point out any number of similar titles, Igarashi and his team arrived at a functional, repeatable design -- and Symphony of the Night came quickly enough on the heels of the acclaimed Super Metroid that it could become entrenched as a formula.

"I think it wasn't until Symphony of the Night and its sequels melded Super Metroid and Castlevania that the classification narrowed to mean something like, 'Side scrolling action-adventures with a obstacles in a continuous map that you can surmount only after finding the requisite items and backtracking,'" says Tom Happ, whose upcoming Axiom Verge is one of the most promising new titles in the genre.

The next turning point for the Metroidvania was the seminal 2004 indie title Cave Story, created by Daisuke "Pixel" Amaya all on his own. It wasn't just a highly creative evolution of the genre; Amaya's ethos of building the game by himself made it a title that is inextricably linked with the rise of the indie movement, and the game's art and design have proved as influential as Amaya's D.I.Y. production style.

Cave Story+

Cave Story+

2009's Shadow Complex, developed by Chair Entertainment for Microsoft, is also worth mentioning. Its massive commercial success as the console market for independently developed games began to take off showed that the genre had a viable future.

That's not the only reason it's notable. "One moment that always stood out to me was when Donald Mustard said (to you, no less) that Super Metroid was 'the pinnacle of 2D game design'; I kind of feel that was the first moment somebody really tried intentionally to make a 'Metroidvania' rather than just an action-adventure with aspects of Super Metroid or Symphony of the Night," Happ says, referencing my 2009 interview with the Shadow Complex creative lead.

Now that it's an entrenched genre, developers are trying to capture the essence of the Metroidvania -- and to extend it further. I spoke to a number of them to find out why and how they're doing it.

My first stop was to ask these developers what makes the genre so enduring -- why does it fascinate today's independent teams? After all, it's been a niche for years and years; it's only recently, post-indie boom, that the number of games exploded.

"The concept is universal," declares Erik Umenhofer, developer of Temporus. James Petruzzi, of Chasm developer Discord Games, agrees: "I think the core mechanics are timeless: exploration, character improvement, platforming, and combat."

Chasm

"I figure it's the excitement of enjoying the adventure, mixed with gameplay that's easy to get comfortable with. I think the exploration element makes you feel like you're moving the story along yourself a lot better than with titles divided into stages. That, and I think having character-growth elements allows gamers to enjoy the story right up to the end," says Igarashi, when discussing the genre's appeal.

"Platformers have always been an easy, up-front genre to get into... Compounded to those simple mechanics, the addition of backtracking, upgrading, power-upping and accessing new areas... adds a lot of spice to how the adventure opens itself up for the player, giving her/him the impression (even if it's a false one) of being inside a very big context that's ready to be explored in a multitude of ways," says Alonso Martin, developer of Heart Forth, Alicia.

"You are the story. You are the adventure. It is up to you to discover where to go and unearth the mysteries of the world you're stuck in," says Renegade Kid's Jools Watsham, who recently launched his own Metroidvania, Xeodrifter. He sees the genre as a way to offer players a game that focuses on "exploration, freedom, self-improvement, and overcoming previously impossible challenges."

It's the genre's blend of elements that has made the Metroidvania so enticing to players and developers both, says Umenhofer: "It's everything that you want out of an indie game. Not a huge time commitment, easy to play, fun and challenging, and usually relatively cheap to make and buy."

Symphony of the Night's map screen. Source: GameFAQs

The focus on exploration that Watsham touched on is a major part of the genre's appeal, if the words of these developers are anything to go by.

"In this genre the phrase 'knowledge is power' -- something we are taught all our childhood -- is true in a literal sense," says Andrew Bado, developer of the upcoming Legend of Iya. "At least that's why I love the genre -- to explore and discover and learn about the world I'm let loose upon by the creators."

"I think it's extremely important that players guide themselves because, ultimately, it is something the player should do. Personally, I prefer, instead of going to a park to play, I would rather go to ruins to play. Because you can think, feel, and search, for yourself, your own way to play," Cave Story creator Daisuke Amaya told me in 2011.

"Nothing is more exciting than possibility," says Matt White, developer of Ghost Song. "True discovery is only possible if you can find things that you may not have, and have experiences within a game that you may not have."

"I like it when you play through the game and learn things piece-by-piece, and that's very important. There's things like the gameplay system that you just learn it as you go along," Amaya says.

"Giving the player a sense of discovery is a crucial part of good game design, even if it's a 'fake' sense of discovery. ... Metroidvanias are at their best when the players are progressing on their own accord, or at least that's what I think," says Jo-Remi Madsen, of D-Pad Studio, developer of Owlboy.

Happ concurs: "The semi-openness of the map design gives it the feeling that you're not just experiencing a scripted sequence of events, but causing the events (in some cases not always in the same order)." And that "allows players to really get lost in the world," says Petruzzi.

Guacamelee

There's a long-term advantage to this kind of design, too: These "labyrinthine worlds filled with secrets encourage healthy communities of dedicated players who continue to play for years," says Jason Canam, game designer at Guacamelee developer DrinkBox Studios. And that capacity for replayability "is where a game can go from fun to legend," Umenhofer says.

"Well, certainly, when we were making Super Metroid, I thought, 'I want to make something lasting that will be fun even if played much later.' All I can say is I'm really happy that we succeeded in that goal. But, if I had to take a guess as to what the lasting appeal is, perhaps it's the impression left on people by the drama of the game," longtime Metroid series developer Yoshio Sakamoto told me in 2010.

If anything, Super Metroid's reputation has actually increased since 1994. That natural drive toward replayability -- which anybody who's given Super Metroid or Symphony of the Night a second, third, or fourth spin knows well -- energizes hardcore communities, says Canam: "The genre lends itself quite well to speed-running and gameplay optimization... These games are continuously mined for new strategies, exploits and shortcuts."

A Super Metroid speedrun race, from Awesome Games Done Quick 2014

While the developers I spoke to are fans of classic titles in the genre, that's not the only thing that drives them toward developing new Metroidvania games.

"The child-like sense of wonder and exploration is something that can be very magical. That is what draws me to the Metroidvania genre. It can be exciting, scary, thrilling, and extremely rewarding," says Watsham. His approach to designing Xeodrifter was a case of "looking inside and seeing what my inner child wants."

Xeodrifter

Xeodrifter

As White has it, "I want to pretend the game world I'm playing in is indifferent to my presence -- I want it to feel as though I'm just a guest in this world, and it'd go on existing and being there whether I set foot in it or not."

Happ also makes a subtle but significant point about how these gameworlds function for players: "In a way the beaten path of the game exists just as an established baseline to allow off-the-beaten-path exploration."

The world-structure of the Metroidvania allows designers to add a variety of ideas, Amaya says: Cave Story is "everything that I like; whether it fits the world or not is secondary, and comes after I decide. That's why there are so many different elements to those caves. I really like how the fans see all of those different elements and reconstruct a world for themselves."

Canam offers another perspective on what the gameworld can be: "Level design is, at its core, all about how the player interacts with an area or locale, but in a Metroidvania game, since the storytelling is related to the player's progression, then the level gets to be a character in its own right. I think of the level as an adversary that the player will encounter, explore and eventually overcome. It's very satisfying to create and (hopefully) very satisfying to play!"

Canam and Amaya aren't the only ones who argue that the genre offers a rewarding space for designers to work in: "The creation of the genre is a lot of brain candy from a design perspective -- a pain, a challenge, but a lot of fun. It's an excuse to draw copious amounts of paper diagrams, create maps and compile spreadsheets balancing all the moving pieces that are inherent in a Metroidvania," says Chris McQuinn, game designer on Guacamelee.

Watsham suggests that while the design challenge is large, cracking it pays creative dividends: "It's you against the odds, and when done right, it can feel more real than many other genres due to the mysteries and challenges you overcome with your own personal growth and progression made over the course of the game. The Metroidvania genre is a microcosm of life's journey itself."

"For myself, as a developer, it largely comes down to what would be most enjoyable to develop. I like exploration, and designing hidden rooms with secret items," says Happ. But there's more to it than that, he says. "There is a real danger that you can get discouraged and quit if the actual work of making a game becomes tedious. So this genre accomplishes most of what I like while still being a viable thing to do all day long."

Igarashi offers these up-and-comers some words of advice: "What it comes down to, I think, is this question: As the people making the game, how are you going to take what you think is interesting about the game and communicate that to other people? With games, even if you create an interesting and fun concept, that's not going to come across if the controls make it impossible for others to realize it. Thus, I think it's important to remember that the core of any game lies on top of how it's controlled by gamers."

"One thing I'll say is that if you don't think that your game is fun, I doubt anyone else playing it will find it fun either. Feedback from other people is vital! Take in this feedback, and, if you can make it work with your own vision, implement it. If you can't, make sure you have a clear reason why."

Sakamoto had these words, when discussing keeping the Metroid franchise alive across a variety of different studio collaborations through the years: "What you're dealing with is a large vessel that is very firm and can hold all of those elements and still retain its own identity. The best way to accomplish that, to find that sort of firmament that you can then put different arranged elements into, is to find the things that you can't budge on -- find the things that are essential, important, and you don't want to change."

These words seem apt to designing any game in the genre.

Given these designers' faith in the genre and its flexibility, it's no surprise they think there's a lot of design space left to unearth.

White suggests one concrete way to move the genre forward: "I think de-emphasizing 'hard progress locks' (e.g., you cannot get to Area 2 until you have the high jump boots because you simply can't jump up to it without them) and placing more emphasis on 'soft locks' (this area is really, really tough until you get stronger, but you can technically go there any time you want) is a good way to go for Metroidvania games, especially those in the tradition of Metroid, and it's a direction I personally plan to embrace more in the future."

Though it's rarely mentioned in connection with the genre, the original Dark Souls is essentially a 3D Metroidvania, structurally speaking; however, progress is primarily bounded by the player's ability to both find new areas and survive in them.

If the key of the Metroidvania is its world, then White sees plenty of room to grow: "I think the best way to look forward is to increasingly incorporate dynamic content, at least in part, into Metroidvania games. A world that seems to think and operate on its own leads to further immersion: I think this is the future."

Unepic

Unepic

But there are simpler ways to inch forward: Francisco Tellez de Meneses extended the Metroidvania with Unepic by fusing it with tabletop RPG mechanics and telling "a funny story not seen before" in the genre, he says. The resulting game very much has its own personality.

"In terms of the games themselves, of course, the ways you can think about it are limitless. If developers can find more ways to present it, then they'll be able to do more things. I think there's a lot of space to keep going," says Igarashi.

But how to find that space? Of course, developers are looking backward for inspiration. But they're also looking side-to-side -- and, of course, outside games, too.

"I think it is possible to continue making new experiences in the Metroidvania genre that stay true to its roots while providing something fresh, and I also think there are even more possibilities for the strengths of the genre to be combined with other genres to create interesting and exciting experiences," Watsham observes.

"Luckily, with so many Metroidvania games coming out, it's helpful that we are able to look laterally as well as forward. You can get inspiration from lots of games that are doing great things with the genre," says Canam.

"Most of what is new is just well-forgotten old, no?" asks Bado, who plans to bring gameplay ideas from non-Metroidvania classics into his game. Martin is adamant, meanwhile, that playing games is essential for designers: "Studying other people's work teaches you things that would take you much longer to learn on your own." Otherwise, you end up "learning to reinvent the wheel."

"Ideas are all about their execution and their context," he says.

Heart Forth, Alicia

Heart Forth, Alicia

To that end, Umenhofer plans to pick "a few games and just shoot for a 'vibe' instead of a replication" of their gameplay. "I ask questions like 'how did Cave Story make me feel in this particular part?' instead of going frame-by-frame analyzing a scene."

Happ believes that, like any creative work, inspiration for a Metroidvania can extend to "books, movies, things in nature, things that happened in my life."

"What makes me curious? What makes me anxious? What situations made me feel helpless? What situations made me feel triumphant?" he asks. Those are fodder for Axiom Verge.

For a genre with a name steeped in nostalgia (the term "Metroidvania" itself being a portmanteau of two classic games, after all) the developers I spoke to are all interested in what they can bring to it -- "more concepts around time travel and how that impacts your landscape in a 2D world," levels that are "procedurally assembled from hand-designed rooms," to bring variety for players who choose to replay the game, or a "self-reflexive take" on the genre "in an interesting, David Lynch kind of way" (Umenhofer's Temporus, Petruzzi on Chasm, and Happ's Axiom Verge, respectively.) These developers do not lack ambition, even if their road has been well-tread.

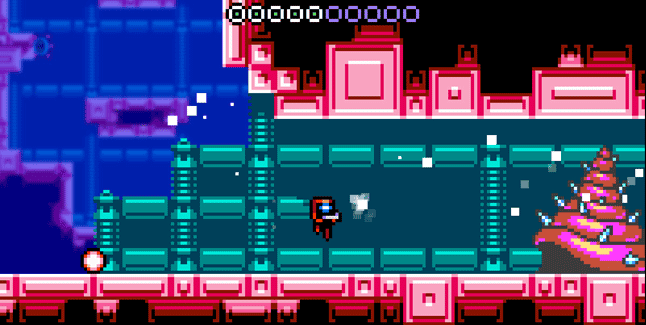

Axiom Verge

Axiom Verge

However, Petruzzi cautions that "players are looking for new experiences that feel fresh, but don't ignore all their favorite games from the past."

In respect to that, Happ sees some problems with the genre's popular appellation: "It's a bit too limiting, I think, to be a movement. I don't want to set out and say, 'Okay, what kind of Metroidvania can I make next?'"

"Being able to explain your game in as few words as possible can be very powerful," is Watsham's take, however -- and a valid counterpoint.

Happ sees "a lot more" potential, if we're willing to widen the genre back up: "Basically, infinite. I think we're kind of tentatively probing the boundaries to see what's possible.

"I mean, take Fez -- it's basically a Metroidvania without combat or upgrades. And then Hohokum, which abstracts it even further. It actually has a very similar layout to Fez with doors and hubs and also doesn't have combat, but when you're playing it, Metroid and Castlevania are the furthest things from your mind. But there is that core."

There's no doubt the genre will continue, and that developers have embraced it. The next step in its evolution will be a broad one that will show us what its true potential is.

Want more? Christian Nutt spoke to a number of developers about the roguelike genre.

You May Also Like