Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This article concerns the dramatic value of player-character motivation and in story-driven games. The featured case studies illustrate techniques for adding a second narrative layer to game objectives, and how this layer can heighten player immersion.

Copyright ©2017 Chris Solarski (SOLARSKI STUDIO)

My second book was recently published by CRC Press. Titled, Interactive Stories and Video Game Art, I'm very proud that it has been described as gaming's equivalent to Story, the classic book on screenwriting by Robert McKee, and endorsed by film director, Marc Forster. This article—kindly sponsored by the SAE Institute Zurich—explores a key concept that I developed in the book called the unreliable gamemaster. This article concerns the dramatic value of player-character motivation and in story-driven games. The featured case studies illustrate techniques for adding a second narrative layer to game objectives, and how this layer can heighten player immersion.

SPOILER ALERT: before proceeding, readers should be aware that the article contains spoilers for the following films and games: Wreck-It Ralph (2012), Halo 4 (2012), Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016), The Beginner’s Guide (2015), Firewatch (2016), Gone Home (2013), and The Usual Suspects (1995).

Making a distinction between a protagonist’s wants and needs is a basic consideration for anybody who has studied screenwriting. To paraphrase artist, writer and filmmaker, Iain McCaig:

“Someone has a want, but obstacles must be overcome to achieve that desire, with the toughest being a hidden obstacle inside them (their need). In the end, the protagonist gets what they need but not necessarily what they want.”

Wreck-It Ralph’s greatest obstacle is overcoming his material want and realising his spiritual need in Wreck-It Ralph (2012), Walt Disney Pictures, directed by Rich Moore.

These motivations (wants and needs) are aptly illustrated by Wreck-It Ralph, directed by Rich Moore. The film makes for an interesting reference for the way in which storytelling is generally handled in games because it’s a satire of game design tropes. In a world where good is always good and evil is always evil, Wreck-It Ralph, a villain, dares to defy convention and become a hero. This want, he dreams, can be achieved by winning a medal. However, at the end of the film he overcomes his biggest obstacle, himself, and learns to become selfless and care for others—the true traits of a hero—which he achieves by helping Vanellope von Schweetz win a medal. This final show of empathy is Wreck-It Ralph’s hidden need, which gives emotional value to all his preceding, self-centred deeds. Based on this example we can refine our concept of wants vs. needs with the following statement:

This is a general theme of most stories in film and literature because the internal conflict between a protagonist’s wants and needs is a powerful catalyst for overt drama—adding depth to a simple risk-and-reward narrative structure. You can also reference The Matrix (1999) and Neo's want to remain a regular guy versus his need to accept that he's The One; or Jaws (1975) and chief, Martin Brody's, want to catch the killer shark versus his need to confront his fear of water. If a narrative focuses too much on fullfilling the want and not enough on the need, the audience will perhaps experience visceral gratification, but little spiritual fullfillment. In game design we must also acknowledge the wants and needs of the player when structuring a story. The motivations of the player and playable character need not be the same but the intended aesthetic experience should align if the story is to deliver its intended message. I will therefore refer to both the player and playable character as the player-character—a single entity—wherever applicable.

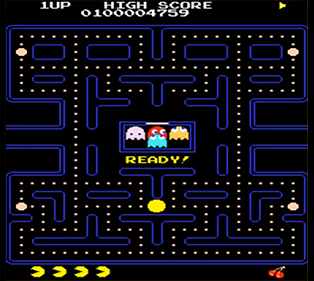

The overachieving gameplay objective (the player’s want) in PAC-MAN (1980), by Namco, is clearly depicted atop the screen.

Classic video games like PAC-MAN (1980) have a fairly simple task of aligning the motivations of players and playable characters. We must assume that Pac-Man wants to avoid ghosts and stay alive. The want of players is usually reflected in gameplay objectives—the overarching task players are given to perform. Objectives in classic games tend to be communicated through the user-interface (UI). PAC-MAN’s designer, Toru Iwatani (1955-2017), boldly stated the game’s overarching objective by inserting the word “HIGHSCORE” and an accompanying counter at the top of the screen. This objective is clearly a material want that encourages players to keep Pac-Man alive to better their score and jostle for the #1 spot on the leaderboard. While the player’s need—the hidden obstacle inside the player—is the time and dedication needed to master PAC-MAN’s gameplay.

The dialogue between a game’s designer and the player—as illustrated by PAC-MAN—is deliberately straightforward. PAC-MAN is a formal game so the objective of play must be communicated clearly if players are to understand the game's rules and objectives and respond with correct inputs to win. The purpose here is pure play from which emergent stories are generated ("I was cornered by Pac-Man Ghosts but just managed to escape through a tiny gab!"). If a scripted narrative features in such a game it is merely a wrapper. The narrative could be interchanged with any other and the emergent stories would remain largely unchanged—such as the stories that emerge when playing Chess with medieval-themed versus Star Wars-themed pieces.

Echoes of this structure that consists of formal gameplay with a narrative wrapper is evidenced in many contemporary story-driven games, even though gameplay has a different status compared to games like PAC-MAN. In the case of story-driven games the narrative should dictate the shape of gameplay—not serve as a mere dressing—if the intented dramatic experience is to be evoked.

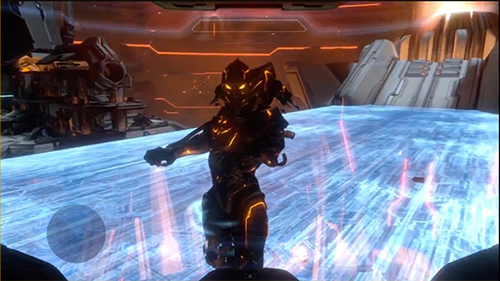

In Halo 4 (2012), by 343 Industries, the AI companion, Cortana, serves as the game designer’s mouthpiece—communicating a breadcrumb trail of objectives that players must overcome.

Take for instance Halo 4, which features Cortana—the player’s AI companion in the single player campaign. Cortana serves a similar purpose to a narrator by providing backstory and tactical information. More importantly, in the context of this article, she serves the same function as Iwatani’s “HIGHSCORE” because we can likewise perceive the game designer’s disguised voice when Cortana gives commands such as:

“They found the opening. You better get up to that relay, and fast.”

“Power core down. Shield’s weak, but still online. Take out the other two power cores and we can access the pylon.”

“Second power core offline. Good job, Chief.”

[…and so on.]

The player’s want is fulfilled in the final gameplay moments of Halo 4 (2012), by 343 Industries, when the Didact is defeated.

What is the player-character’s overarching motivation in Halo 4? The want is to defeat the Didact—the game’s primary antagonist who Master Chief (the player) unwittingly awakens early in the game. This want is, unsurprisingly, fulfilled at the game’s end, with the help of Cortana who sacrifices herself to save Master Chief. This unquestionable route to victory is a general trait of formal game design, which is humorously expressed in the trailer for Insomniac Games’, Sunset Overdrive (2014):

"Can you save Sunset City? Of course you can! It’s a f@*king video game!”

You could replace “Sunset City” with the overarching objective of most story-driven games. The rationale is clear: with a formal game design structure there must be a payoff. Players can't be expected to play through X hours of gameplay and not be rewarded with their want. However, the downside of this structure is a loss in dramatic tension since the outcome is instinctively known to players from the outset.

But what about the player-character’s need in Halo 4? If we examine the in-game action, alone, we find that Halo 4 demonstrates little concern for aligning the motivations of players and the playable character, Master Chief. Based on the formal structure of the game we can deduce that the need of players is time and dedication to master Halo 4’s gameplay and “unlock” all cutscenes. Does Master Chief share the same need?

The profound need in Halo 4 (2012), by 343 Industries, is revealed after the players want has been fulfilled—thus rendering it ineffective to the player’s own experiences.

We find that Master Chief’s need is much more profound, however, it’s mostly set-up and delivered through cutscenes—such as mid-game scene in which Cortana pleads: “...before this is all over, promise me you'll figure out which one of us is the machine.” Another crucial point is that the need finds closure in an epilogue cutscene after the player’s final encounter with the Didact. During a sombre discussion with Captain Lasky, a battle-worn Master Chief laments the loss of his AI companion:

Master Chief: “Our duty as soldiers is to protect humanity. Whatever the cost.”

Lasky: “You say that like soldiers and humanity are two different things. Soldiers aren't machines. We're just people.”

[Dramatic music begins playing…]

Unlike Wreck-It Ralph’s toughest trial, which is the external staging of his internal conflict, the player-character’s need—to question their humanity—is absent in the gameplay finale. Instead, the decision is made on behalf of the player, rendering the need’s revelation completely ineffective as a dramatic device. A significantly more compelling solution would have demanded that players must choose between sacrificing themselves to defeat the Didact, or allowing Cortana to sacrifice herself for a greater good—thus placing the “big question” in the hands of the player.

Players of Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016), by Naughty Dog, achieve their want of finding Avery’s treasure at the end of the final mission in a boss fight with primary antagonist, Rafe Adler.

The interactive narrative in Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End shares many of the same shortcomings as Halo 4. Objectives are similarly implied, through the banter between Nate and his comrades—Elena, Sam, and Scully—during cutscenes and in-game action. The following are a few excerpts:

Prologue

[In-game] Sam: “Keep heading towards the island. I’ll try to hold them off.”

Chapter 1: The Lure of Adventure

[In-game] Nate: “Up and around we go […] Okay…nice and quiet […] Gotta get to that window.”

Chapter 10: The Twelve Towers

[Cutscene] Nate: “Alright, this route here should take us straight to the volcano.”

[…]

[In-game] Scully: “So, what are we looking for out here?”

Nate: “Well, the map shows all these structures around the volcano. Some abandoned outposts, a handful of watch towers. […] One of those towers is right on the volcano.

Scully: “With Avery’s treasure?”

Sam: “Fingers crossed.”

As with the commands issued by Cortana in Halo 4, the banter represents the disguised voice of the game designer, which defines the player’s objectives. And, as with Halo 4, there is a misalignment between the motivations of the player and playable character. The banter between in-game characters generates in players the want to find Avery’s treasure. During Chapter 20: No Escape, this want is substituted by the want to save Nate’s brother, Sam, but the narrative leads player’s to the treasure anyway, so the original objective is achieved. With such an objective-driven structure, the player’s need is, once again, time and dedication to master Uncharted 4’s gameplay and unlock all cutscenes.

A mostly forgettable cutscene during Chapter 19: Avery's Descent, in Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016), by Naughty Dog, is actually an important dramatic moment where players witness the awakening of Nate’s hidden need when he finds his wife, Elena, feigning death.

Uncharted 4’s narrative does feature a profound need, which is reserved for the playable character, Nate, and his tenuous commitment to married life with his wife, Elena—a commitment that conflicts with his loyalty to his brother. Nate who, like Sam, doesn’t know when to quit, “no matter the cost to others around him,” must put his love for Elena before treasure hunting. This need is ineffectively conveyed to players through cutscenes, with Nate inconspicuously making the important realisation long before the player’s final battle at the end of Chapter 19: Avery's Descent.

A more fitting ending for Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016), by Naughty Dog, would have challenged the player-character’s need during Chapter 20: No Escape when Nate is ready to give-up on treasure hunting.

Uncharted 4 could have challenged the player-character’s need in a more meaningful manner if the game had ended at an earlier juncture—during Chapter 20: No Escape—when Nate is ready to give-up on finding Avery’s treasure but his brother, Sam, wishes to fight-on. At this point Nate reflects on Sam’s want as if simultaneously commenting on the game industry's preoccupation with reward-driven objectives: “We're not those kids anymore. And we’ve got nothing to prove.” What if at this point gameplay demanded that players choose between destroying the mountain and forever losing the treasure, or going after the treasure and forever losing Elena?

By comparison, action films like Iron Man 3 (2013) are no better at challenging the spiritual needs of the protagonist (Tony Stark's want to defeat the enemy versus his need to devote himself to Pepper Pots). Here, also, visceral gratification trumps spiritual fullfillment. We should therefore be aware of the standards that we're setting by championing games like Uncharted 4 for their story when they're structural comparible to an Avenger's movie. Instead, such honours should go to the games explored in the following sections.

Having reviewed the wants and needs of players and playable characters in Halo 4, and Uncharted 4 it is worthwhile adjusting our original definition of motivation it to fit narrative structure of these two games:

“The player-character is given a want, but obstacles must be overcome to achieve that desire, with the toughest being the final level or boss fight. In the end, the player-character gets what they want while the need is experienced by the playable character, only—not the player.”

This is true of many AAA titles that prioritise formal game design over narrative even though their promotional trailers and cinematics suggest an emotionally-complex narrative experience. Games are about player agency—not passive viewing—so the backstory of such games should be central to the player-character's experience and expressed through their actions.

The reason why we studied how player objectives are communicated—via Cortana in Halo 4, and through cutscenes and in-game banter in Uncharted 4—is to highlight the game designer’s in-game communication with players, which is a key concept for understanding how the misalignment between the wants and needs of player’s and playable character’s can be solved for story-driven games. Halo 4, and Uncharted 4 are examples of a formal dialogue between the game designer and player based on explicit objectives and consistent rules with escalating difficulty for dramatic effect. The term I use for the role of such a game designer is the reliable gamemaster—an entity perceived within the game world that guides players to fulfil their want with fair and open communication of the game’s objectives and winning conditions.

Forrest Gump (1994), and The Usual Suspects (1995) exemplify the unreliable narrator device.

A key to solving the want vs. need conundrum (academically referred to as ludo-narrative dissonance) takes inspiration from a traditional literary device called the unreliable narrator. An unreliable narrator is a narrator—whether in literature, film, or theatre—whose credibility is questionable. Sometimes the narrator's unreliability is made immediately evident, such as the slow-witted Forrest in Forrest Gump (1994), whose observations of the Watergate scandal and description of Apple Computers as a "fruit company" are clearly not accurate. Alternatively, the narrator’s unreliability can be revealed at the story’s end for greater dramatic effect—such as the spectacular revelation at the end of The Usual Suspects (1995). The gaming equivalent of the unreliable narrator, as used in Forrest Gump, and The Usual Suspects is experienced in two video game masterpieces by designer, Davey Wreden: The Stanley Parable (2013), and The Beginner’s Guide (2015), respectively.

The Stanley Parable (2011), designed by Davey Wreden and published under Galactic Cafe, is an exceptional critique of formal game design where players can actively question the game designer’s authority.

Players of The Stanley Parable are accompanied by an off-screen narrator who attempts to guide the them through a sequence of actions. However, the game’s level design allows players to “misbehave” and choose their own path—to the exasperation of the narrator who responds with comic effect. The tense dynamic between narrator and player is illustrated by the above scene where the narrator is heard saying:

Narrator: “When Stanley came to a set of two open doors, he entered the door on his left.”

At this point the player can choose to follow the narrator’s instructions, or disobey and choose the door on the right. If the player chooses the door on the right, the narrator reacts accordingly:

Narrator: “This was not the correct way to the meeting room, and Stanley knew it perfectly well. Perhaps he wanted to stop by the employee lounge first, just to admire it.”

The narrator in The Stanley Parable is, of course, the game designer in disguise—much like Cortana in Halo 4. Only the important difference here is that the game designer’s motives are questionable and players have the option to act against designated objectives. The narrator’s reliability in The Stanley Parable is questionable from the outset while Davey Wreden’s next game, The Beginner’s Guide, reveals the narrator’s untrustworthiness at the end. In both cases, the role taken by Davey Wreden is that of an unreliable gamemaster—an entity perceived within the game world that conducts an informal dialogue between the game designer and player based on vague or questionable objectives for dramatic effect.

How does the unreliable gamemaster concept solve our want vs. need conundrum, which must consolidate the objectivity of formal game design’s emphasis on winning conditions, and storytelling’s emphasis on the player-character’s internal conflicts? By using this approach, players are encouraged to actively question their purpose in the game, which awakens their senses and makes them feel more present within the virtual world. Designers can misdirect players to a false objective (a want) without appearing unfair, while secretly embedding the real objective—the player-character’s need—into gameplay. An additional benefit of the unreliable gamemaster is that the informal dialogue between the game designer and player can generate dramatic tension as a result of the narrative’s ambiguity, without resorting to escalating gameplay difficulty.

The player-character in Firewatch (2016), by Campo Santo, wants to solve the game’s explicit objective concerning the mysterious figure that torments Henry and Delilah.

Take for instance Firewatch, by Campo Santo, which exemplifies the unreliable gamemaster concept in the form of Delilah who guides the player from one objective to the next. Unlike Cortana in Halo 4, Delilah remains a mysterious character that the player never meets. Her role is that of a fellow victim struggling alongside the player-character to make sense of the mysterious happenings. A dialogue excerpt between Delilah and the player-character goes as follows:

Delilah: Hey. You…you didn’t actually make that call, right? To the other lookout? It just stuck in my craw. I let myself imagine how f@*ked I would be if you’d if you’d been lying to me. But now that I’ve asked I kinda just wish I hadn’t.”

Henry (player-character): “Of course I didn’t. No way. They’re just trying to pit us against each other.”

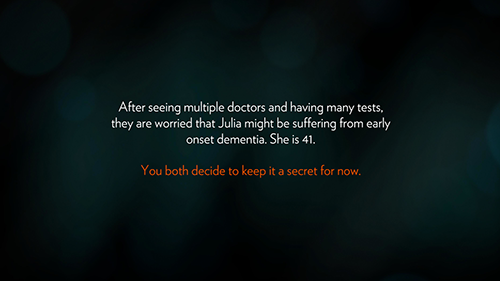

The player-character’s need in Firewatch (2016), by Campo Santo, is planted at the beginning of the game but soon forgotten when the want becomes the primary objective of gameplay.

Delilah assists the player-character in solving Firewatch’s explicit objective, which is to solve the mystery of the strange figure who torments the two characters with actions that include ransacking Henry’s watch tower, and framing them for starting a forest fire. This want is fulfilled by the game’s end and the mystery is solved. However, on reflection, players of Firewatch will realise that the ultimate goal is not the explicit objective that they’ve been pursuing. The objective is, in fact, a need to empathise with victims of dementia—a fact that was hidden in plane sight all along.

In the heartrending opening of Firewatch, players learn that Henry’s wife, Julia, falls victim to an early onset of dementia. The eventual fate of Julia is what leads Henry to become a fire watch lookout. Framed in this context, the player’s experience of dislocation, fear and confusion as a victim of the mysterious figure is analogous to somebody experiencing dementia. Player’s therefore experience empathy through a gameplay form of allegory, because the playable character, Henry, can be said to represent his wife, Julia. The ability to interactively experience themes as complex as dementia is what makes video games such a powerful artistic medium.

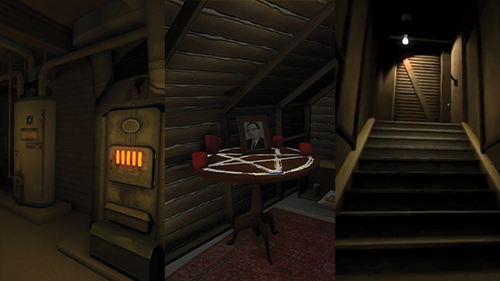

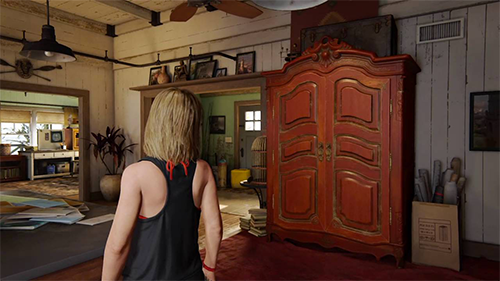

The setting of Gone Home (2013), by The Fullbright Company, is used to misdirect players into thinking their objective is to discover the dead bodies of Sam and Lonnie.

Gone Home, by The Fullbright Company, also uses a variation of the unreliable gamemaster to misdirect players towards a false objective. The game has players following a breadcrumb trail of audio diaries and written notes that gradually reveal a love story afflicted with teenage angst, social pressure and parental disapproval. Fairly unremarkable storytelling. What makes the experience special is that the game’s setting resembles a haunted house, replete with a spooky boiler in the basement, empty hallways and occult motifs. Immersed in this setting, players expect to experience the hallmarks of a horror story, such as jump scares and a bloody ending. However, by the game’s end they are rewarded with genuine catharsis when they fulfil the explicit objective—the want—and learn that the love story has a happy ending. The hidden need is revealed to be the overarching experience of navigating the haunted house-style setting (an “unreliable environment,” to put it another way), which generates feelings of fear and isolation that are analogous to the experiences of an 18 year-old girl experiencing the uncertainty of her first love and sexuality.

What Firewatch, and Gone Home have in common is an explicit objective that motivates players to act and a second, more meaningful hidden objective. In hindsight, players realise this latter, hidden objective, was embedded in gameplay and evident all along—like a successful plot twist. The unreliable gamemaster therefore allows us to successfully reconcile the original definition of character motivation—as demonstrated by Wreck-It Ralph—with story-driven game design:

“The player-character is given a want, but obstacles must be overcome to achieve that desire, with the final obstacle heralding the player’s hidden need (such as empathy for the playable character). In the end, the player-character experiences what they need but not necessarily what they want.”

INSIDE (2016), by Playdead, demonstrates another variant of the unreliable gamemaster in which exposition is avoided altogether—leaving the task of interpretation entirely to players.

Another effective variation of the unreliable gamemaster is to remain silent, as in INSIDE (2016), by Playdead, which generates many questions through it’s visual design and staging but offers no answers. Irrespective of the exact techniques employed, you’ll find that a large majority of emotionally meaningful games to have emerged in recent years—including Braid, The Last of Us, Portal 2, The Beginner’s Guide, and Her Story—utilize the unreliable gamemaster concept.

But, to be fair to 343 Industries and Naughty Dog—the developers of Halo 4, and the Uncharted series, respectively—developing multi-million dollar games is very risky business considering the work involved to produce such high quality gameplay and graphics. Which is why it makes for a safer financial bet to stick to tried and tested formulas to meet the target audience’s expectations of big boss fights, action set pieces and explicit rewards. Additionally, imagine the difficulty of developing a sequel to Uncharted 4 if Naughty Dog had indeed given players two options to finish the game—requiring narrative designers to account for both outcomes. Series like Call of Duty, Assassin’s Creed, and Batman Arkham all fall into this same category of video game storytelling, consisting of a narrative wrapped around what is clearly a formal game design structure. This works for formal gameplay franchises like the Mario series, but not in self-proclaimed story-driven games. No matter how glossy the cinematics and set pieces may appear—the formal roots of these games are very much intact.

Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016), by Naughty Dog, bravely features gameplay vignettes that offer players a more emotionally-rounded experience than if the game focused purely on action-adventure.

It is of no surprise that innovation in storytelling is strongest within the indie game scene where development costs are significantly lower and target audiences more open to new and surprising experiences. AAA is taking note, nonetheless, as evidenced with the gameplay vignettes scattered at a few points in Uncharted 4 (the salvage diving, and Crash Bandicoot sections, for instance). These vignettes give players a more rounded and emotionally-meaningful interactive peak into Nathan Drake’s family life—particularly the ending where players take control of Nate’s daughter, Cassie. Gameplay moments like these are an important primer for the existing target audience of such games—opening-up player expectations to the direction that storytelling in games will inevitably take as game development and the player audience matures.

Formal game design focuses on objective (as opposed to subjective) rules and player goals. These game mechanics are great at motivating players to action—to explore and interact with the game world. However, in the context storytelling, game mechanics also have their shortcomings because they gratify the player’s material wants by virtue of their tangible qualities.

Storytellers in mediums such as film are well aware that the greatest narrative tool is the audience’s imagination. The same is true of video games where the player’s imagination has the greatest freedom to subjectively (mis-)interpret the rigid structure of game rules. While game mechanics are great at motivating players to act, it’s game art (visual design, voice acting, music, etc.) that can make something as simple as going from point A to point B feel treacherous, cheerful, solemn, lonely…

The next generation of game designers should therefore aspire to develop a greater understanding of traditional art forms; their aesthetic scope and interconnectedness; to appreciate the strengths of informal game design for stimulating the player’s imagination; to enable player-choice; and avoid exposition where possible. In essence, to be unreliable gamemasters—using storytelling techniques inspired by the above case studies to antagonize, mislead and silently direct players towards experiencing a hidden need at the game’s dramatic climax. In hindsight, player’s will come to reflect on a gameplay experience and realise that clues hinting at their need were embedded in gameplay all along—directly beneath their noses—in the same way that Wreck-It Ralph’s want blindly guides him towards the realisation that a medal doesn’t make a hero. In storytelling it’s more often the journey, not the destination, that matters.

Thanks again to the generous support of SAE Institute Zurich, and game designers, Claudia Molinari and Matteo Pozzi (We Are Müesli), and Madlaina Kalunder for their invaluable feedback. To stay updated about my latest work you’re welcome to follow me on Facebook and Twitter.

---

Chris Solarski (SOLARSKI STUDIO) is an expert on art and storytelling in video games. His first book—Drawing Basics and Video Game Art (Watson-Guptill 2012) is endorsed by id cofounder, John Romero, and has been translated into Japanese and Korean. His second book—Interactive Stories and Video Game Art (CRC Press 2016)—has been described as gaming's equivalent to Story, the classic book on screenwriting by Robert McKee, and endorsed by Hollywood film director, Marc Forster. Chris has given talks worldwide, including the Smithsonian's landmark The Art of Video Games exhibition, SXSW, GDC Europe, and FMX. He is currently collaborating with internationally renowned artist, Phil Hale, to develop an indie game based on the Johnny Badhair series of paintings.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like