Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"We didn't take into account how much work there is with the interface in such a game. But we don't regret the choice."

Have you ever wondered what would happen if the bizarre beasts on medieval manuscripts gained sentience through the power of sorcery and threw down? The development team behind Inkulinati has.

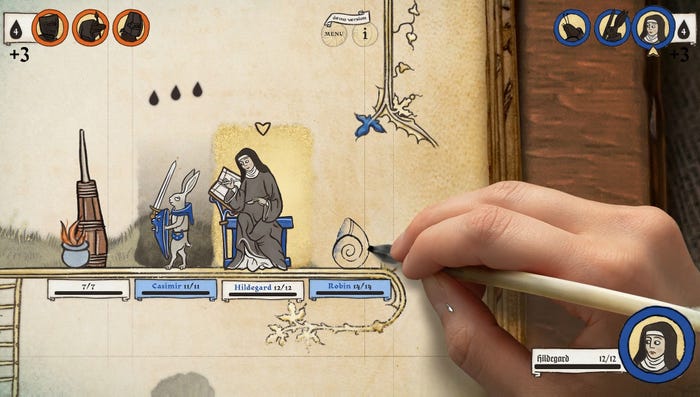

Yaza Games' unique strategy title is a turn-based battler that allows players to become Inkulinati, masters of living ink who are able to turn sword-wielding rabbits, human-eating snails, and other abstract apostils into fervent paper-bound fighters.

The game leans heavily on tactics, asking players to define their own style by building a bestiary from a selection of magnificent marginalia with their own strengths and weaknesses. The levels themselves also contain unique dangers and obstacles, but can be altered using special tide-turning actions performed by Inkulaniti themselves.

Although Yaza Games is still working on the title ahead of a planned 2022 release, lead designer Wojtek Janas and art director Dorota Halicka agreed to provide an extraordinarily in-depth look at Inkulinati's combat systems ahead of time.

Yaza Games disclaimer: At Yaza Games we are often not unanimous, which we think is one of the most important features of our team, because it allows us to analyze problems in more depth. As such, we prefer to point out that opinions are unique to individual game developers.

Game Developer: Why did you opt for turn-based combat? What was it about that system in particular that appealed to you?

Janas: Quite quickly we decided to make the game take place on the pages of medieval manuscripts. Then we looked through subsequent fragments of marginalia, i.e. decorations on the margins of medieval manuscripts, which Dorota, our art director, searched for. We had a few ideas for the genre, but when we saw the fragment with rabbits fighting dogs -- we immediately knew that a turn-based tactical game would be the best solution

Ms 107, Bréviaire de Renaud de Bar (1302-1304), fol.-89r-137v, Bibliothèque de Verdun

This setting is more suited to the slower pace of the game -- creating ornaments on actual manuscripts took a lot of time back in the day so the reflexes of a chess player are more suited here -- therefore a turn-based strategy seemed like a natural choice. It was also about the achievability of the challenge for a novice team. We thought a strategy game was easier to develop, though we didn't take into account how much work there is with the interface in such a game. But we don't regret the choice.

Most of the team liked turn-based games, and had played HOMM3, Worms or Civilization at one time. Not only was turn-based strategy the right genre for our project, but it certainly was something personally important to all our individual team members.

We also felt turn-based strategy would give us the opportunity to create more complex and original mechanics, and that creating real time strategy in a flat space limited to the pages of a manuscript might not give us as much opportunity to "go wild" creatively as a turn-based strategy. I still feel that this was the right track.

Finally, the choice left a lot of room for humor in a turn-based game. The idea of creating a hot-seat mode so players could celebrate that humor together was something very appealing.

Did you need to make any considerations to add complexity to combat in the 2D space?

Janas: We needed a lot of thought, but not to add complexity to the combat system. As novice developers, designing a system that was probably too complex came quite naturally.

Still, we needed a lot of iteration, discussion, and time to create a game that has depth and complexity, while still being easy to understand and play. It was also important that the mechanics create a cohesive experience. So it wasn't achieving complexity that was the challenge, but finding a way to keep that complexity from becoming overwhelming.

In pure design terms, we were heavily inspired by the scenes we found in the marginalia, which is why the beasts can perform various actions, often ones that are not associated with combat -- like pushing, praying, playing the trumpet. This made it very easy to create complexity, because mechanics like pushing or making music in games don't have very strong patterns, so there was room for original ideas that can surprise the player, which is one of the layers that make up the complexity of our combat system. The idea is that we're not so constrained by the habits of players from other games, which allows us to explore a slightly different approach to turn-based combat with more freedom.

It may seem that one of the biggest challenges was limiting the battlefield to the space of the book, but it wasn't really that difficult. By having a limited space we were able to focus on designing small battlefields from the beginning, before trying to exploit their potential by maximizing positional importance. So it was not a challenge, but a creative constraint.

Halicka: The starting point for the game were animal fights on the pages of medieval manuscripts. During the creation of the first prototypes, the whole game world and the so-called "meta" layer were also created. The inspiration to close the game world in the book was for me the solution from Hearthstone - the whole game is a kind of wooden box with a board and cards to play. In our case it is a book. During the research I also came across the so-called "Girdle book" -- portable books of small format, worn behind the belt. Since we had hot seat battles and animal fights on manuscripts in mind from the very beginning, we needed to explain the two sides of the conflict. That's how we landed on the idea of dueling Inkulinati -- members of a secret society, who duel by means of quill and living ink on the pages of medieval books.

The idea of enclosing everything in a book was a very important decision that strongly influenced the whole thing. We limited the battlefield in this way -- characters have a certain amount of space, the world is not "infinite." This made it easier to work on the game from a technical point of view -- setting the camera distance, the resolution of individual elements, the size of the board graphics, e.t.c. It also influenced the gameplay and the look of the interface. Menu screens are successive pages of the book, popups are scraps of parchment, gilding is highlighting the buttons, and so on.

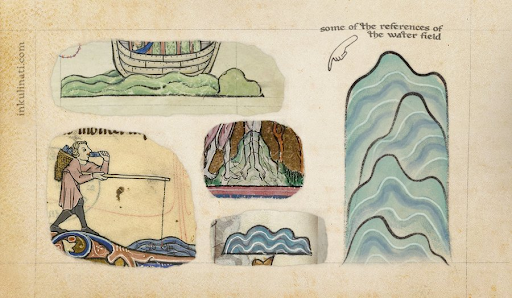

Anonymous medieval scribes and illuminators are our concept artists. Medieval marginalia turned out to be ready-to-use concepts for units, board elements, battle types and level design. The game world is built on references from the marginalia, which have their own visual rules. For example, most representations of medieval water in manuscripts resemble blue hills rather than our modern image of water:

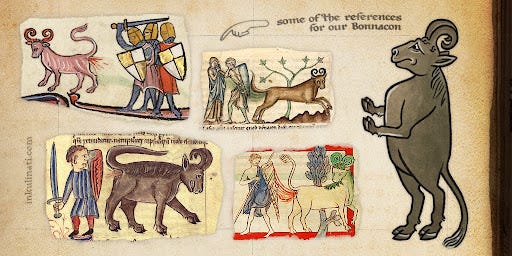

Also, each of the characters we find in the game have their origins in manuscript references, such as Bonnacon:

Some of the scenes seen in the digitized collections turned out to be ready-to-use battlefield inspirations:

Marginalia also has its own specific 2D gravity, similar to a Super Mario game; more on that in an interesting article here.

Using strictly public domain references, and delving into the beliefs and convictions of the time, we have created a unique and unusual game world. We try to make it coherent, both visually and in terms of content, while making sure that the game is accessible and understandable.

Where did you look for inspiration when designing Inkulinati's combat system, and how did you look to iterate on your own terms to ensure the game's skirmishes stand out from the crowd? Is this where Perks come in?

Janas: There were many, very different inspirations. We didn't want to make a copy of an existing game, and just put it in a medieval marginalia setting. I think we wanted to create an original game from the beginning, where the manuscript setting is the dominant inspiration. So we tried to sensibly combine a variety of inspirations -- primarily the marginalia, but also Monty Python’s humor, Worms, Homm3, Steamworld Heist, elements from Yoshi titles, and our own answers to the question: what could you do with Living Ink?

However, that sort of "cooking" takes a very long time. Part of the inspiration and mechanics we drew "with tweezers" from other games. We came up with many solutions based on manuscripts, and then we looked to see if something similar had already existed somewhere, and we didn't always find it. The process of creating a coherent combat mechanic for this reason took quite a long time, because we had the individual ingredients, but the recipe had to be created by ourselves on the fly.

A little more about the individual inspirations:

We associated animal fighting with the Worms series. The strategy-arcade nature of Worms seemed like an interesting lead for us.

SteamWorld Heist - because it's one of the few strategy games with a view and plane similar to our game.

Monty Python - the humor of the marginalia and that of Monty Python seemed to work for us, especially since I've been a big fan since childhood. Besides, Monty Python also took on the marginalia in the Holy Grail.

Heroes of Might and Magic 3 (HOMM3) - one of the most important games of my childhood, very popular in Poland, here we were primarily inspired by the combat system, although over time our game has evolved so much that most of the similarities are blurred, but I still think that you can feel the inspiration.

Yoshi - arcade mini-game mechanics. We felt that we needed some unexpected element in the combat system itself to make the combat mechanics as distinctive as the setting. This was also the reason why we included the push off board mechanic in the game.

How did you work on subsequent iterations on your own terms to make duels unique from other games? Did you introduce Perks into the game for this reason?

Janas: What did we do to make the game stand out from the crowd? We prioritized the compatibility of mechanics with the setting. The main thought for us here was "what could really happen in the manuscripts if the Living Ink existed and secret Masters met for legendary duels?"

The uniqueness always came from looking for solutions consistent with the manuscript references. If a problem arose we looked for solutions from other games, but also deeply analyzed source materials. We even read about beliefs from that period. This meant that we often came up with completely different ideas from those featured in other titles.

We also consulted regularly with a Medievalist, Lukasz Kozak, who would provide tips on the logic of marginalia or the Middle Ages. A lot of unique ideas came from his knowledge of the Middle Ages. Often the key factor in evaluating ideas for what to include in a game is historical consistency and whether the item contains specific marginalia humor. We consider whether the item can be found in manuscripts, or whether it was an important part of life in medieval times, or is something medieval people would have laughed at.

From there, we came to the conclusion that the game wouldn't be historically correct without the depiction of a trumpet in a butt. We had to be brave enough not to censor some elements of history for fear of people's reactions. That's why fecal jokes are still present in Inkulinati -- otherwise, we wouldn't have captured the spirit of medieval illuminators' work. And they would probably turn over in their graves and we simply couldn't let that happen!

Halicka: We abandoned some of the references that were too problematic thematically and symbolically. For example, Owls are today considered as symbols of wisdom, and back then during the medieval times they aroused much more negative connotations. Back then, marginalia pieces also often depicted male genitalia. You can find all sorts of such depictions, from flying penises to a tree on which penises grow, and they are picked up by none other than a nun. This is an idea that we unfortunately had to abandon. Ratings are important in the games industry and social media relies heavily on algorithms, so we had to make tough decisions and give up on this. But we are still considering it for optional adult DLC in the future.

We also have contacts with groups of enthusiasts of this historical period, with whom we can consult regarding, for example, the shape of the gauntlet, or other visual aspects. We also try, on our part, to be historically consistent, and certainly to make sure that elements of the game have their references in the manuscripts. Every element and every character has their source in the manuscripts.

In terms of references, rely primarily on European manuscripts from around the 11th-14th century. Most were based on Christian iconography; the entire construction of the depicted world referred to and intertwined with this religion. The blessing, the bishop, Hildegard, the heretics, the prayer, the altar, the bell tower, the cloud from heaven with the blessing -- these are some of the elements that we use in the game and that are based on manuscripts that were written in Christian Europe. We try to be consistent with that historical period.

For example, if we were making a game based on Japanese manuscripts -- we would take into account the iconography, religion and beliefs of that period and region. Also, the visual layer of the game would be different - it would be based on the graphic techniques existing in the given region and time.

Janas: We tried to draw the setting from the Margins in a variety of ways -- humor, appearance, but also the basics of combat mechanics. One example is the pushing system. Since there were a lot of different things going on in those marginalia pieces, we wanted actions other than attacking to be meaningful. So that when you play the game, you actually recreate different situations you can see on the manuscript pages, not just the standard weapon attack. Hence the idea of praying or pushing other beasts. In the beginning, it was supposed to be just a malicious action, without much strategic importance. However, when we added the possibility of pushing the enemy outside of the battlefield, the game took on a completely different dimension and depth, which directed us to completely different, more interesting paths for level design and the mechanical design of Beasts and Inkulinati. It increased the importance of level design and made the different shapes of the battlefields take on additional depth.

Another case in point. We wanted to have an explosion mechanic, on the one hand as a tribute to Worms, but above all we thought it would be something that would add a lot of variety to the gameplay. Of course, we also wanted to be historically correct -- as much as you can when you think about explosions in the Middle Ages, of course. Following the idea that humor should be more or less as important as that accuracy - we opted for flatulence as something that would both fit into our quirky internal logic and be in the spirit of the marginalia.

This is one of the reasons why it takes so long to make Inkulinati; if we weren't making a historically accurate game, we could use red color and put 'tnt' text and everyone would understand that the item could explode.

We felt it made sense in our game that someone who overeats too much would explode at the moment of death. Especially since we knew the story (even if false) about the king who died of overeating. We also didn't have many alternatives. Back then, in the 12-14th century, as far as I can tell, there were no bombs as we know them today (at least in Europe, and certainly in the manuscripts), and the attempt to use the then-familiar Greek fire for this purpose really disgusted some fans ("It was more like napalm, not a bomb!" we read [in] the comments).

Additionally, we were inspired by the explosion of a restaurant guest from Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, and the marginalia themselves, apart from fights or scenes of everyday life, also feature visual representations of defecation, chaotic monkey parties or farting. Our medievalist, Łukasz Kozak, with whom we work, also sent us a medieval story about a villager who fooled the devils who came for his soul by farting into a sack and telling them that his soul was inside. So we had a sense that this could make a person living in the Middle Ages laugh. This is one of the reasons why it takes so long to make Inkulinati, if we weren't making a historically accurate game, we could use red color and put 'tnt' text and everyone would understand that the item could explode. But we had to combine things, and so one of the challenges for explosive bloat was the question 'what should bloated Beasts look like to make it readable for players that they would explode when they die,' and here there was no reference from other games, so it cost a lot of time.

Perks, or Talents, are there for a different reason: they provide more replayability to the game. They're not necessary to make individual battles interesting, but they do guarantee that the game will stay fresh through multiple playthroughs, because these talents are a sort of modification of the rules, providing the ability to create synergies specific to a particular battle or to a particular approach to the campaign. Something like the relics in Slay The Spire, but adapted to our mechanics.

What were the most challenging aspects of creating a turn-based combat system with depth and clout, and how did you overcome those hurdles?

Janas: I'm going to list some of the main challenges because it's hard for me to pick the biggest one:

1) Putting together different ideas (we have too many of them, help!) into a coherent whole, so that the setting and mechanics are inseparable

Solution - work, iteration, amendments, discussions, analysis. There are no shortcuts, you just have to have time for it.

2) Making mechanics clear and understandable for the player (we still have a problem with this, but previously we were at the point where the player had no idea about key mechanics)

Reconciling the depth of mechanics with the ease of control and UI probably takes us the most time. We learned everything in this aspect while making Inkulinati, as it was our first game as a studio. For example, the first version didn't have an automatic end of a turn -- there was no visual indication of which beast is currently selected -- so we lacked the absolute basics in terms of communicating to the player what is happening on-screen, which meant that at game industry events we constantly had to sit next to players and explain to them what was going on. I don't recommend it. It's much better to be able to watch from the side how the players themselves deal with the game.

An additional challenge is our goal to be true to the Marginalia style, which meant the UI not only had to be readable, but also look a certain way. Of course, that also extends to other areas such as battlefield elements . We couldn't make a first aid kit to communicate "hey, you heal on this field!". That's why we have clouds with a hand that heals, because it fits our setting better. So a similar case as with flatulence and explosiveness.

Implementing our ideas in a way that players could understand was sometimes a challenge. For example, in order to provide more depth to the gameplay we added a second way to win. You collected points for epic combos on the battlefield. Unfortunately, although this mechanic was very interesting and fun, it turned out that adjusting the UI so players knew exactly how to get those points was beyond our capabilities. One of the biggest lessons I learned when designing a mechanic is to immediately create a visualization of how it will be presented in the game. If you have a problem sketching it, it probably means that the implementation of a given mechanic will be very time-consuming.

In the beginning we also didn't show the transitional states of each beast clearly enough, i.e. bonuses or debuffs - such as the fact that someone is a heretic (i.e. exposed to stronger attacks from the Bishops). In the beginning it was a small symbol next to the character's name. Nobody saw it. It was only when we made a dark halo (the opposite of the golden one, reserved for blessing or prayer) dedicated to Heretics that people started to notice that something was going on. Among other things, we created a status system after this experience - each status is now visibly marked on the Beasts themselves. Even if players don't understand a status, they can see that something is currently "going on" with the Beast, so they have a chance to look for it in the tooltips. Previously, only we were able to distinguish who was a Heretic, but by the time of testing, we thought that this marking was sufficient. It turns out regular testing is indeed essential when making a good game.

3) Getting players to use mechanics other than attack wasn't easy! From the first version of the game, the various Beasts had several action options besides attack, but players were not very keen to use them -- probably because attack was the most understandable. To solve this problem, several actions were needed.

In the first version you could not pray - you could kneel, which was a defensive action - a kind of defending yourself, only in our opinion a bit more ridiculous. We felt that it somehow referred to prayer, so it should be understandable. The assumption was also that kneeling would protect against being pushed. However, both the mechanics and the name didn't suggest it was worth using and no one used it during testing, especially since at that stage pushing didn't seem particularly strong to the players. So we changed the name to prayer and it was more associated with some kind of power. As a consequence of the name change, we also changed the mechanics. We added halos and from then on prayer, apart from defense, strengthened attack power. By then, players were already more willing to use this action. But it wasn't until the push mechanic was added and therefore provided the ability to push Beasts off the board that the prayer action gained key tactical importance. This is one example of why it takes so long to create Inkulinati - some of the mechanics had to mature to blend into the whole combat system and take it to the next level.

As for pushing -- people understood the power of this mechanic only after the AI started using it well, and when we added visualization when choosing a pushing target. Before that, some players found the move illogical and were asking for changes in how it works. But the action itself we didn't want to change, because what people were asking for could mess up the whole combat system. So we introduced a dedicated GUI element, a line that shows where the object will stop when pushed. Since the introduction of this visualization, nobody has complained about pushing. It turned out that the mechanic itself was fine, and that communication (or rather a lack thereof) was the issue.

4) Player understanding of the setting - a lot of players who were not familiar with the manuscript theme had a problem entering this world

The setting concept for our game assumed that there was a secret group of Inkulinati, forgotten by historians, who dueled each other on the pages of medieval manuscripts, and that what we can see today in digitized collections are the remains of these duels. In my opinion it is an interesting, unusual concept, but it is difficult to explain in words.

Since we have experience with filmmaking (I graduated from film school and previously was a film editor, Dorota graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts and previously worked as graphic and motion designer) we decided to use our skills to make a short feature film. We were helped by friends connected with the world of film and art, as well as medievalists and reconstructionists. Thanks to their support we were able to make a film with a very low budget - lower than its quality indicates.

We used the footage as a marketing asset for our Kickstarter campaign, but also as a game intro that introduces players to the atmosphere and setting of the game without words. Focus studies have shown that players understand the game better if the setting is clear to them, and indeed - thanks to the intro we don't have to explain so much in words what the game is about, so most players will probably rate the game higher than if the intro wasn't there.

Halicka: 5) The big challenge was (and still is) to create a world presented in which names, iconic design, character design, graphics, descriptions and plot all explain each other and create a holistic visual-plot sense.

I'm curious to know how you balanced and tweaked the Inkulinati themselves to ensure they felt chaotic and tide-turning without seeming overpowered? Could you talk about some of those abilities, and how you conceptualized and developed them throughout production?

Janas: By way of introduction -- we have the Inkulinati, or Masters of the Living Ink, in the game -- their large, realistic hands intervene on the battlefield. We also have Tiny Inkulinati. They are miniature portraits of Inkulinati, who act as the most important beasts of the given army and thanks to which we can summon Inkulinati hands during the battle. Losing a Tiny also means defeat in a given battle.

We quickly decided that the characters we would meet in the game would be unusual, distinctive figures associated with medieval culture. Of course we wanted them to use strategies consistent with their appearance and character. Hence the decision that a well-known knight will primarily attack, and St. Hildegard - healer, church reformer - will heal and use cat bishops. We rely either on real historical figures - such as those mentioned above, or Dante Alighieri, or those found in reference manuscripts - such as the Master. This assumption was the basis for the design of the Inkulinati.

The ability to come back is mostly a matter of synergy of three mechanics - push, linking defeat with Tiny's death and Apocalypse. In the beginning you had to destroy both Tiny and other enemies, but it was not very clear to the players and the push mechanic was not that valuable. Now, when you can inadvertently lose because someone pushes you away - comeback is something that can happen even in a situation of a big disadvantage. Of course, other mechanics - like Tiny’s actions - also allow you to turn the match's fate, but without the possibility of pushing Tiny, such situations would happen less often.

As for the design of the Tiny's themselves, at first we thought of a king figure in chess. But then we changed them to inkwells for a while. It seemed consistent with the logic of Living Ink. However, attacking an inkwell is not much fun, and such an inanimate object generally evokes less excitement than a "living" character. And since different characters are to be in charge, it's good for them to have unique abilities. Hence the dedicated hand and beast actions are assigned to specific Tiny Inkulinati.

Above all, we wanted the Inkulinati to be different, asymmetrical to other Inkulinat Mastersi, and for their strength to depend on who they were playing against, and on what map. So I can't answer whether Godfrey or Hildie is stronger - it depends on the specific battle, player preference. Certainly, Godfrey is easier the first time you play, but Hildie has more opportunities to disrupt your opponent's plans by healing allies, and thanks to the rabbit action, which shows its butt and "paralyzes" your opponents. The idea was that playing each Inkulinati would be a different experience and require different strategies - for example, one of the new Inkulinati will be focused on interfering with the battlefield, instead of directly affecting the beasts - this gives the feeling of playing this Inkulinati in a different way. It adds freshness to the game.

As for the power of the Tiny Inkulinati themselves, we balance this by changing the range of actions, the possible frequency of use, and the strength of the impact of the action. In the beginning, the range of Tiny actions was unlimited, which gave them more power but made the game too chaotic, because it was hard to defend yourself and have effective techniques against Tiny actions. Now, with limited ranges, there is an additional tactical layer -- when to start storming the enemy’s Tiny Inkulinati and when to keep your distance? If we don't get close it will be difficult to finish them off effectively. If we get close we expose ourselves to their actions. This very nicely adds to the importance of the positions the beasts occupy, which is very important with limited battlefields.

The players themselves in the campaign will be able to choose their own Inkulinati and will create their own sets of Beasts, Hand Actions, and Talents. This will guarantee a more replayable campaign.

While we're on the subject of balancing, how did you design the title's weird and wonderful bestiary and manuscript battlegrounds to support a variety of tactics and playstyles?

Janas: Here I would like to explain that the word Bestiary can be understood in two ways - Bestiary can mean a collection of Beasts, which we have chosen for the game, but it can also refer to medieval Bestiaries, which described various Beasts, which were believed in those days and now we know that they never existed (like Dragons or the Bonnacon), but also real animals (like rabbits). These medieval Bestiaries were of course ready from the beginning of our work on the game. It was enough to look into them and get acquainted with the works of our concept artists -- the medieval illuminators. Of course, there are many more Beasts out there than we would be able to put in the game, so the selection process was important, as well as the "translation" of medieval descriptions of Beasts into game language and mechanics.

It was a long process. In the beginning we wanted to give the players full freedom, so they could draw both dogs and rabbits during the battle. Then dogs were just better versions of rabbits. Then our medievalist stated that mixed armies of dogs and rabbits are rather rare in the manuscripts, and that it would be better to add different factions (interestingly, he had no problem with rabbits forming an army together with cats or snails). This improved the players' perception of the game -- they could identify more with their army -- so we also then started to differentiate the Beasts more, so that they had different mechanics and created synergies within their army.

Before implementing a new beast we've always done beast research, consulted with our medievalist Lukasz about what was written about these creatures in medieval texts, and from that, we've tried to create mechanics consistent with the rest of the combat system -- preferably one that's also full of humor. Battlefield elements, on the other hand, utilize mechanics created during beast creation, increasing the importance of army placement on the battlefield.

We wanted to leave players a certain amount of creativity in how they play battles, and to provide a sense that they can play in different styles, even within the same army. For example, the whole Heresy mechanic comes from thinking about what was important in the Middle Ages, and what the Bishops could bring to the game. So a Hildie army can either focus on crippling enemies by showing rabbit asses, or you can draw Bishops and try to attack Heretics. Of course, these strategies are not mutually exclusive and can be mixed in the course of a single battle.

Replayability was important to us, so we added options to randomize battlefield elements or random events with unpredictable effects. Because of this I like to sometimes think of our game as a series of generated tactical puzzles.

For more variety we have also introduced so-called Wild Battles -- that means battles with only one Tiny or no Tinys at all. These are faster skirmishes where all warriors of at least one army are on the battlefield from the very beginning. It doesn't seem like much of a change, but it does force players to choose different strategies while using the same mechanics, which feels fresh. Especially since Wild Fights are interspersed with normal Tiny vs Tiny (i.e. Inkulinati vs Inkulinati) duels.

What's more, with Wild Fights we can create something more along the lines of puzzles with a specific solution, giving players the opportunity to learn and appreciate the abilities of various Beasts in a more interesting way than just reading tutorial pop-ups.

We balanced the armies so that each army was unique, but we didn't try to balance each Beast separately so that they were more or less similar in strength. It's the context of the battle that determines the usefulness of the Beast. For instance, a donkey farting on a trumpet can sometimes be the worst choice in a given situation, and sometimes it can tip the scales of victory. Of course, what we were doing was making sure that the more expensive Beasts were appropriately stronger than the cheaper ones. On the other hand, I wanted to make it unclear as to whether you should buy a more expensive Beast or two cheaper ones -- in different situations the answer will be different.

Finally, what were the most valuable lessons you learned as you sought to devise a system that's adaptive, flexible, and importantly, fun?

Communicating the mechanics. The player must be in touch with them at all times. Even the best mechanics, if poorly communicated, will add nothing to the game except confusion.

When designing a mechanic, immediately create a visualization of how the mechanic will be presented in the game (you can use a piece of paper, photoshop or video editing software - whatever will best help you visualize how the mechanic / UI element works, etc). If you have trouble visualizing it, it probably means that implementing the mechanic will be very time consuming. It also helps to create a description like "what the player sees," "what happens when the player clicks a button," "what they see."

One of the most important things for us have been video visualizations. Before we got down to the first version, based on a common understanding, I made a visualization-animation depicting how the interface works alongside 60 seconds of gameplay. It was quite ugly, but achieved its goal nonetheless. The whole team then knew what we were aiming for with that first iteration.

We did the same with all the more complicated game elements or mechanics - such as when we talked about how we wanted the campaign to look, or when we wanted to re-do the interface. It took us a day or two to create each visualization, but it allowed us to immediately see problems that wouldn't be that obvious from a written description, which can be interpreted in a variety of ways. It also makes the creation of trailers or other more complex assets much easier. It's an approach I'll definitely be using on future projects. I highly recommend it.

Dorota: From the beginning of the work on Inkulinati, we as a team use visualization/mockup animation, in order to be sure that all team members are on the same page of vision of the game.

This one (above) is the very first mockup animation, done before the main work on Inkulinati started. This was the first time when all team members caught up in terms of the vision of how the game will work (which changed several times after this, and we had to catch up with the vision regularly).

See how much changed, and how much is still similar since then.

Halicka: Look for the sweet spot between taste and readability. Avoid mechanics that are too clichéd but also great ones if they are too complicated or unintelligible. Sometimes you have to remove the most interesting element of the game, so that the rest of the game creates a coherent dish (just like it is better not to add 50-year-old whiskey to milk soup).

Just because someone is having fun, doesn't automatically mean they will want to come back to the game. If the first battle tires the player out with its length and amount of new information, it is possible that they will feel exhausted afterward. You have to take care of the length of the basic gameplay loop, because even a fun game can easily become tiresome.

Making a game with original mechanics with millions of inspirations can take forever. And while it's fun to prototype the next tasty mechanic, at some point you have to set milestones and get into production by consciously limiting your creative power. You have to redirect it to solving specific problems.

Controversial mechanics are not bad, but you have to be aware that they are controversial. Then it will be easier to interpret the feedback. In our case, the arcade mini-game is controversial -- some players drop out because of it, but turning off the mini-game really "flattens" the excitement of the game, and most are happy with it, even if the unhappy ones seem louder. That being said, we know we won't please everyone, but we choose what we feel is a more intense experience and what ties the whole game together.

Regular testing on people outside the team is essential to making a readable tactical/strategic game, because we often don't realize something is completely incomprehensible. Also, you can't make a game by finding out what the problems are only by yourself. I feel that a production cycle works well where the players provide the problems, and the developers provide the solutions. You can't make a game and come up with all the potential problems and solutions internally -- it simply needs to be shown to players many times at different stages of production.

You May Also Like