Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this thought-provoking design piece, writer Sande Chen (The Witcher) takes a look at how to ratchet up emotional intensity - through narrative design, visuals, and music - to create more meaningful games

[In this thought-provoking design piece, writer Sande Chen (The Witcher) takes a look at how to ratchet up emotional intensity - through narrative design, visuals, and music - to create more meaningful games.]

While games have come a long way, developers have yet to take full advantage of the medium by incorporating meaning within the very structure of a game. Time-tested techniques from film can help, but first they must be adapted to fit the unique properties of video games.

One of the strongest tools to convey meaning is thematic expression, which can be integrated not only in narrative, but also in other game elements, such as art direction, game systems, sound design, and music. Developers who yearn for mass-market appeal can use this multidisciplinary approach to create meaningful and more emotionally charged games.

"If we're going to build really powerful games, we need interdisciplinary teams," says Sheri Graner Ray. As a freelance game designer and production consultant, Ray knows firsthand the level of collaboration that can occur when artists, writers, designers, programmers, and composers work together.

In particular, Ray advocates bringing in a writer or narrative designer early enough in the design process so that the game can have more depth. A programmer wouldn't be expected to know which colors evoke which feelings, Ray points out, so why would anyone without training or experience presume to take on the role of the narrative designer?

As champions of the story, narrative designers are more than just dialog writers. By using themes and other tools of storytelling, they oversee the process of crafting a meaningful experience throughout the game. Themes, like an emotional heartbeat, enable stories to deliver a universal message, yet also resonate with players at a personal level. Thematic expression can surface in the narrative, art direction, game systems, sound design, and music. As such, the role of the narrative designer is inherently multidisciplinary.

Themes also are likened to the game's or author's point of view. "Even in games," says narrative designer Stephen E. Dinehart, "we seek to communicate a message."

The theme gives the reason why this particular story should be told. Often, to find these meaningful themes, writers soul-searchingly delve into a personal credo to discover where their passions lie - because to convey passion, one should be passionate about the underlying message. Because themes are best felt at the subconscious level, a writer must be careful not to be preachy and instead, let the theme flow from the situations presented in the story.

The integration of themes is what elevates a film to cinematic art. Developers of video games can adapt the very same techniques used in film to create more meaningful games. Just as films have stirred passions, evoked emotions, and even encouraged real-world action, so too can games.

Much as the Munsell Color System provides a way to specify a particular color of value 8 and chroma 2 without confusion, Bruce Block's visual theory of cinematography gives a common language for developers to discuss visual components.

As described more fully in his book, The Visual Story, Block discusses how film directors use the narrative structure as the basis for cinematography decisions. Color, tone, shape, line, angles, lighting, and camera movement are all choices that reflect theme and affect how audiences feel about a character or setting.

For example, ambiguous space can create anxiety, confusion, or tension in a horror flick.

Curved lines have a more whimsical quality than straight lines. A car zooming diagonally across a frame looks sleeker and speedier than if it were travelling horizontally. Likewise, a composition built around triangles will be more visually intense than one centered around round shapes.

Furthermore, a director can use affinity and contrast to control visual intensity.

Although all of these visual elements do elicit general emotional responses on their own, a director can assign further meaning to each element.

In the 2004 movie Hero, directed by Yimou Zhang, the color green signified vengeance, red stood for passion, and white denoted truth. These artistic decisions were governed by the director's interpretation of the screenplay.

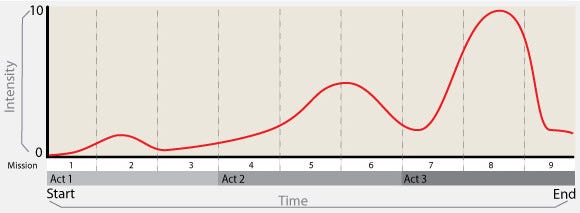

As seen by the accompanying graphs, each visual component can be mapped to the story. The first graph, depicting story intensity, shows the standard rise and fall of a linear narrative.

A visual component can stay constant, follow the story, or perhaps it spikes based on some story events. The screenplay serves as a blueprint for the visuals.

Block's visual theory applies to any time-based visual medium, such as video games. Obviously, not all of these visual components can be controlled during a video game, but some, like color, tone, shape, and line quality, clearly can be used to make a game stronger.

For the game Company of Heroes: Opposing Fronts, Dinehart created the following Game Intensity Graph to generate a color script.

Peak intensity for the game and story occurred during "red" missions while "green" signified a return to normalcy. This loading screen, a prelude to the final conflict, shows affinity of color.

Even in situations where there aren't traditional narratives, these visual principles still apply. Advertisements and music videos may not have stories, but they have structure. A music video director can use the structure of verse and refrain or possibly tie the rhythm of visuals to musical intensity.

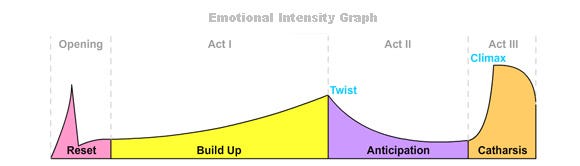

In this example, Jenova Chen, creative director of thatgamecompany, plots out a game's Emotional Intensity Graph, which could later form the foundation for visual design, story design, and sound design.

In his book, Block cautions that the worst visual design is no plan at all. Without a plan, viewers would still have a reaction, but that gut reaction may work against your purpose. "That's just how our brains work," says Drew Davidson, Director of the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University. "We're pattern-making people. We look for things even when they're not there."

Narrative design drives home the meaning of a game. In a meaningful game, art isn't created because it's cool but to convey a specific impression to the player. Filmmakers have gone beyond the cool factor to try to make films that provoke thought. They've already learned that these visual components evoke certain feelings. Now, it's time for video game developers to use visual structure to dramatic advantage.

Narrative design and cinematographic techniques can be embedded into gameplay as well. As Brian Hawkins, CEO of Soma, Inc., describes more fully in his book, Real-Time Cinematography for Games, programmers can create algorithms and agents so that gameplay events have a more dramatic effect.

As lead game core and interface programmer on the game, Star Trek: Armada, Hawkins sought to make the real-time strategy game more exciting by highlighting cinematic events like explosions or confrontations. He took it upon himself to learn cinematographic techniques so that he could program them into the game.

Beyond cinematographic techniques, Hawkins advocates the judicious use of scripted sequences to push forward the narrative. These would not be minutes-long cut scenes, but infrequent pre-scripted moves created for key story moments.

Although many developers despise scripted sequences for taking control away from the player, Hawkins believes that these sequences can be done in a way that would not elicit complaints from the players. "The trick is to take control away from the players without them realizing it," says Hawkins.

In his book, Hawkins describes the creation of a jump sequence for dramatic purposes. Normally, in this hypothetical game, the player jumps from ledge to ledge, but if during a chase, the player slips and almost misses a ledge, this is a matter of chance. The player may recall later, "I barely pulled myself up by the fingers!"

Instead of leaving it to chance, the scripted sequence recreates this moment at a time when it would make the most dramatic sense for the story. The player is still in control of the jump and if the player begins the jump within the confines of a predetermined jump zone, then the player always lands with fingers on the ledge. Outside the jump zone, the player would fall in the chasm as usual. Of course, this jump sequence could only be used once or twice because overuse would reduce the dramatic effect.

Hawkins calls this the video game equivalent of cinematographic "cheating" since players probably wouldn't know the exact distance needed to land the jump. In film, cinematographic "cheating" occurs when props are moved closer to actors in close shots to indicate spatial relationships or when footage from two locations are edited together to make it seem like one location.

In some cases, set designers have actually painted shadows onto curbs. Video game developers often employ "cheating" in other areas, such as in the simplification of physics or accelerated time.

Certainly, scripted sequences are nothing new, but Hawkins calls for a smoother and more subtle approach that would reinforce the story during gameplay. For example, in Assassin's Creed, the player leaps from beam to beam fairly flawlessly because a bumbling goof hardly fits the profile of a professional assassin. In Prince of Persia: Sands of Time, the camera switches position to show a more dramatic view of an elaborate finishing move and then returns back to normal when control is handed back to the player.

Hawkins' hope is to see the creation of director agents that would control the other cinematic agents, like camera, cinematographer, editor, sound editor, and lighting. He concedes, however, that in current console systems, the processing power needed for a director agent would require sacrifices.

Moreover, the director agent would have to be programmed on a per-game basis since each game requires different directing skills. But, he says, "If you're trying to tell a story, then spending more time on the camera might actually benefit you more than adding a few more particle systems to the game."

Even with a director agent, a narrative designer is needed to determine key story events and how that director agent would act in different scenarios. Most importantly, the narrative designer would work with the systems designer to ensure that themes are consistent across gameplay. With gameplay so paramount to a player's experience in video games, it's crucial that developers of meaningful games align gameplay with story.

Sound design and music are often overlooked in games, but they are powerful tools to convey narrative. As in film, game composers know to weave themes into music so that the audience reacts on an emotional level. Such musical themes, tied to particular characters, objects, or places, should reflect the overall narrative theme.

In film, sound and music is used to increase drama. When the script calls for a tense moment, sound or lack of sound builds that tension. When the mood is relaxed, the music is relaxed. When sound and music is working, they are almost unnoticeable under the visuals. Instead, they mesh with the visuals and narrative to create a powerful, immersive experience.

Anecdotally, Davidson recalls a time at a former company when a new build of a game was submitted to a client. Nothing had been added except sound and music. Mesmerized, the client kept on asking what had been done to the visuals to make them so great. Davidson comments, "It soooo gets into our subconscious. That's where I think sound and music have so much power and potential impact."

To build that immersive experience, however, not all sound needs to be realistic. The Foley artists responsible for sound on a film are not required to use whatever object is portrayed on screen, but whatever fits the story better. In a climatic scene of a movie, as in The Matrix, the director may choose not to depict realistic sounds of bullets flying around the room, but a more artistic interpretation.

As always, it falls back to the meaning of the game. That's why it's so important to clue in composers and sound designers to themes in the narrative. Just providing the visuals isn't enough, although it is a good start. Concept art is fine, but a visual plan like that described in the previous section would show progression through the game. Even better would be a full understanding of the key narrative moments designated in the game.

This way, composers and sound designers could build upon their work in a meaningful fashion. Carolyn Fazio, composer and audio director at Sonic Farms, muses, "Maybe in the beginning, your character theme would be simple, but by the end of the game, you'd change your character theme to include your original theme but have it more complex and dynamic to show how your character has grown throughout the game."

As with the narrative designer, Ray recommends bringing in a sound designer and/or composer early as part of an interdisciplinary team. She understands fully the power of sound and music in games. Just recently, she heard the notes from a once-favorite game and experienced an emotional pull back to those times. "I almost got misty over it," she recalls. "It was like a family reunion."

Truly, the emotional heartbeat of a game can be heard through its music and sound design. Narrative designers can work with composers and sound designers to strengthen the emotional connection so that players always have a powerful and meaningful experience.

To build a meaningful game, a narrative designer joins together and balances these disciplines in game development so that the story can shine in a game. When done successfully, the game expresses themes that connect to audiences. It becomes more than simply a game, but a meaningful experience.

As such, Davidson and Hawkins believe meaningful games are the way forward to mass-market appeal. Just as audiences look to film for a variety of topics and meaningful experiences, they seek the same satisfaction in games. By using the same conventions seen in film and adapting them to games, developers appeal to this mass market through its visual literacy.

Moreover, Ray says, "When we build these powerful and emotional games, we build stickiness. We bring our players back, if not to this particular game, to similar games, to our company, to our product lines, because they know they're going to have that type of experience."

By espousing this multidisciplinary approach to narrative design, developers can elevate the art of game development as well as increase the bottom line. Meaningful games require advance planning, but players benefit much from the integration of story, art, gameplay, sound, and music. Using themes, narrative designers ensure that each play experience is not only immersive, but also a meaningful one.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like