Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In which the concept of interaction is discussed, an attempt to understand gameplay through Jungian psychology is made, and a functional purpose of games is proposed.

My purpose last week in discussing the Socratic Method was to attempt to establish that gameplay (as opposed to simulation or demonstration) is a truly dialectical process. This was important in that, if—and this is a big if, but if this is granted as true, it provides the basis for a Jungian analysis of the experience of gameplay. But first, let’s look at the concept of interaction.

The Other of Play

The interesting thing about games is that, within all the possibilities of a game’s mechanics and ruleset, the rules and content which can be known by the player is only that which can be or has been accessed through interaction (barring that the player is given this information from an outside source). In other words, the content depends on the interaction with the player. And this is in more than just the narratological sense that the implied author has simply yet to reveal the next turn in the plot—it is also fundamentally ludic. Just as the player may never know about the Zodiac Spear or that the Bloody Mess trait will cause the Overseer to explode at the close of Fallout, the player may never experience the lawful disbandment of the Skulz, again in Fallout, or the peaceful reunion of the Green Isles in King’s Quest 6. And the part of a game that arises through the player’s interaction—unlike the implied author of a novel—is experienced by the player as an emergent “personality” of that game (the other of play) [recall the requirement of elenchus that at least two voices be heard, and that they must both sincerely defend their positions].

To be clearer, the emergent aspect of a game like Tetris can be experienced as a “personality” in that, because the block being dropped at a given time will constantly change, a player can anticipate that I block forever and even reach a point where it feels as if the game is cheating by denying the player that block when it really should have dropped by now. So when the AI Director (a rather tellingly personifying label) in Left 4 Dead throws 2 tanks in one round, and the second tank comes just as you’re limping down the tunnel to reach the Safehouse while attempting to sneak by a witch; or when you caulk the wagon in Oregon Trail and manage to cross over safely, only to all of a sudden have a thief steal two oxen (How the heck do you steal oxen anyway? The ones that are pulling your wagon. I mean, come on.)…*

I would propose, then, that a game is interactive so long as it upholds a dialectic that is responsive enough to create player investment, which in turn creates the illusion of that emergent personality. To state it another way, a player invested in a game is also experiencing a parallel emergence of an aspect of his psyche that is projected upon the game. And the degree to which a player is invested directly impacts the strength of the illusion of an emergent personality—that is, the strength of the projection.**

The question of what exactly is emerging, then, brings us to the concept of the archetype as delineated by Jung—a notoriously difficult idea to describe.

The Unconscious, the Conscious, and the Archetype

In order to understand the idea of the archetype, it is important to describe the unconscious and conscious as Jung comprehended them. Simply put, the unconscious is all the parts of the psyche which are not conscious. According to Jung, the mind, when first born, is entirely composed of the unconscious, superficially similar to how a stem cell has yet to form into a specialized cell, but still contains everything required to specialize. The psyche only achieves consciousness and understanding by interacting with its environment through the projection of archetypes. This is much in the same fashion that the other of play does not emerge until the moment of interaction. And in the sense that the archetypes are the emergent aspects of the self that arise through interaction, they are “deintegrates” of the self (Gray, 12).

The archetypes, then, are pre-existing thought patterns which manifest themselves independently and autonomously. This results in certain motifs which are repeated throughout different cultures. It is no mere coincidence that Odin’s self-sacrifice on the World Tree is so strikingly similar to, yet arrived at completely independently from, Christ and the Crucifixion.

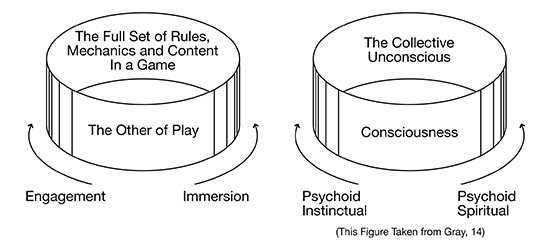

But most important for the purposes of our discussion here is the “two-faced” or bipolar nature of the archetype (Gray, 13). The independent and autonomous manifestations of the archetypes result both as symbolic motifs (psychoid spiritual) and behavioral patterns (psychoid instinctual) that are recognizable and universally repeated—that is, they generate both action and narration (for lack of more precise terms).

So in the Jungian sense, it is not so much that Donkey Kong or DotT marries together gameplay and narrative well, as Mr. Johnson argued last week (which is not to say that they don't, and my apologies if I have understood the argument incorrectly), but that the experience of an archetypal interaction naturally and inevitably produces a symbolic motif. Conversely, an archetype which produces a certain symbolic motif will also produce a specific actional or algorithmic pattern.

And so we have the Twelve Labours of Heracles and the particularly satisfying boss fight only gameplay of Shadow of the Colossus (whose successful completion requires the player to identify the weaknesses or pivot points which allow the player to accomplish the labour); the eternal task of Sisyphus and Tetris; and the class specialization/party system of fantasy RPGs, whose characteristics, though likely tracing their recent origin to LotR, can also be found in the “polyheroism” of the Iliad, the Argonauts, and indeed, the very division of labor and function in polytheistic traditions.

Confusingly, the archetypes are not actually the content of the patterns themselves, but container forms which merely result in similar content. “Jung reflected this when he said that the archetype represents the ‘possibility of representation.’ The content is dependent upon the organism’s interactions with the environment,” (Gray, 46)—a rather familiar thought from our earlier discussion of interaction. As Mr. Johnson noted, the story of Osiris is not actually the archetype itself, merely a manifestation of it. Thus the rebirth of Osiris through the recollection of his body parts, and the reforging of Narsil to signify the return of the King; the completion of the Immortal King set to achieve a set bonus, and the increasing strength of the player as he gains more shards of the Silver Sword of Gith; are all manifestations of the same, pre-existing archetype of rebirth through re-integration.

Finally, Jung further insisted that the archetypes could never be directly described, but only indirectly inferred through their results. They are, moreover, inseparably contaminated with one another, so that the archetype of the shadow can be represented by the Devil, but in the same turn, Satan (whose name indicatively means ‘the accuser”) can simultaneously fulfill the role of the archetype of the wise old man, as in Goethe’s Faust, the Book of Job, or in the story of Balaam’s donkey.

Gameplay and the Archetypes

Mr. Johnson’s equation last week of gameplay and narrative, then, is perhaps quite close to the mark. While I would not venture to argue that they are equal per se, I would however heartily agree that they are nevertheless two sides of the same coin in that the archetypes result in gameplay in which the narrative and ludic (both rather inaccurate terms here, but they must suffice) events are inseparable. This is not to say that the narrative and gameplay in a game are always cohesive wholes—indeed they often are not, and it can even be argued that narrative is optional for a game. But the experience of archetypal interaction will always produce a symbolic or narrational relationship between the player and the game, variously termed “procedural narrative” or “emergent behavior,” etc. etc. If the game's narrative happens to align with the archetypal interaction, so much the better.

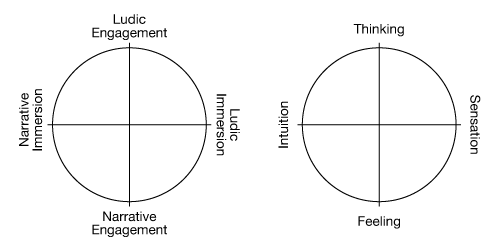

However, I would here like to make a distinction in my usage of the term gameplay. I believe it is no accident that there are two verbs associated with the act of interacting with a game: gaming and playing. Playing is often used to describe the adoption of a position or role, while gaming is frequently employed to describe the act of jockeying for position or active manipulation. For the purposes of this discussion, it becomes convenient, then, to equate playing with immersion and gaming with engagement. So gameplay becomes the combined process of gaming and playing which creates dialectical/archetypal interaction and player investment. These distinctions and definitions are by no means intended to be authoritative, but I have provided them in order that I may more precisely refer to observable aspects of the experience of interacting with games. That said, I would propose the following correlations:

Given the two-faced nature of the archetype and the dual nature of gameplay (and this is not even mentioning the narrative/ludic split), it becomes quite conceivable to correlate the two. Of course, correlation does not mean causation (and this, needless to say, applies to the whole of this post), but I believe it is possible to make at least a very strong case that games are constructs which fundamentally reflect, or are even manifestations of, the archetype of the Self.

The Archetype of the Self

Here, it becomes necessary to define the archetype of the Self, as well as the concept of the ego. As mentioned previously, the psyche is composed of the unconscious and the conscious. The part of the unconscious which contains the archetypes is known as the collective unconscious, or the archetypal psyche.

The archetypal psyche has a structuring or ordering principle which unifies the various archetypal contents. This is the central archetype or archetype of wholeness which Jung has termed the Self. The Self is the ordering and unifying center of the total psyche (conscious and unconscious) just as the ego is the center of the conscious personality. (Edinger, 4)

Symbolically, “images that emphasize a circle with a center and usually with the additional feature of a square, a cross, or some other representation of quaternity,” represent the Self archetype (Edinger, 4).

To clarify, as mentioned previously, prior to the emergence of the ego (that is, consciousness), the psyche is composed entirely of the archetype of the Self (Edinger, 5). Thus the Self archetype represents at once the whole of the psyche, as the conscious arises from it, as well as the center of the unconscious. Psychological development, a process Jung termed individuation, is thus a constant and lifelong cycle between ego-Self union and ego-Self separation.

The occurrence of the cross or quaternity within the square, then, represents the fourfold tendencies of the psyche: the two rational functions of thinking and feeling, and the two irrational functions of intuition and sensation. The following description by Jung of intuition and sensation should help in the understanding of what he meant by “rational” and “irrational”:

Both intuition and sensation are functions that find fulfilment in the absolute perception of the flux of events. Hence, by their very nature, they will react to every possible occurrence and be attuned to the absolutely contingent, and must therefore lack all rational direction. For this reason I call them irrational functions, as opposed to thinking and feeling, which find fulfilment only when they are in complete harmony with the laws of reason. (Jung, as quoted by Sharp)

And again, from Jung:

Merely because [irrational types] subordinate judgment to perception, it would be quite wrong to regard them as "unreasonable." It would be truer to say that they are in the highest degree empirical. They base themselves entirely on experience. (Jung, as quoted by Sharp)

So it is not that the irrational functions are illogical, but that they are unconscious and not subject to conscious reasoning.

Now that the primary attributes of the archetype of the Self have been established, let’s compare it with gameplay.

The Experience of Gameplay

As I mentioned previously, there are two main modes of interaction in gameplay: immersion and engagement. These can then be subdivided into their ludic and narrative counterparts. Here, it becomes immediately useful to draw the following comparisons:

While the above is not meant to indicate direct correlations, it does however provide us a useful (and perhaps unifying) framework to understand the fourfold tendencies of gameplay, particularly in light of Jung’s usage of the terms rational and irrational. While engagement describes active and conscious judgement, immersion describes passive and unconscious perception.

Further supporting the correspondence between gameplay and the Self archetype is a concept which Johan Huizinga famously described in this landmark work Homo Ludens as the “magic circle.” According to Huizinga, the “magic circle” is the conceptual space, or gamespace, which encompasses and separates the player from reality during play. Walther provided this useful insight concerning the concept:

Reality is the horizon that is transgressed in order to play, and it therefore becomes "the other" of play. However, importantly, this otherness also has to abide within play, as it is the latter's indication of what separates it from non-play. Therefore, the other is simultaneously, as difference, and viewed from the inside of play, the unity of play. (Walther, 2003)

Besides that the image of gameplay (of which we have already indicated the fourfold tendencies) invoked here is the symbol of a circle which contains the whole, the above description of “the other” strongly resonates with the concept that the ego arises out of the Self, which simultaneously represents the whole unity and the part of the psyche which is not conscious (note: Walther’s usage of the term “the other” here is not the same concept as I discussed earlier, but is rather the inverse, or what I referred to as “the full set of rules, etc.”).

Assuming these comparisons are reasonably accurate, it then becomes possible to directly compare gameplay to the process of individuation.

Proposal for a Functional Purpose of Gameplay

It has often been argued, if not outright insisted, that gameplay serves no functional purpose than itself—at best it is there for the sake of gameplay. But this very idea that gameplay is the function of gameplay strongly reflects Jung’s “idea of the self as [both] the source and goal,” (Gray, 24).

There is another quality of interaction which has been called flow. Flow, as imprecise as the following description may be, is essentially the state in which a player is both immersed and engaged. This quality has often been described by players as something transcendental but supremely in the moment, meditative yet active—a union with the unconscious, if you will. It is, perhaps, the highest form of satisfaction that can be obtained through games.

Under a Jungian framework, the moment of flow happens when the archetypal action that is occurring through game fully overlaps with the archetypal identity one has adopted through play. This was why it was assumed in my earlier post that role fulfillment within the context of teamwork is possibly the highest form of satisfaction obtainable in a co-op game such as L4D—such moments are also moments of flow, if more the “rational” version of it as opposed to the “irrational” version experienced in racing or music games.

At any rate, the idea of flow is important in that it ties into the concept of individuation, which I mentioned briefly earlier. According to Jung, the ultimate purpose of the activation of the archetypes, and the goal of the archetype of the Self, which Jung called individuation, is to alert the conscious to the presence of the unconscious, an entirely larger and older part of the psyche. Yet the ego, the seat of the conscious, is often mistaken as the whole of the psyche, so the archetypes activate in order to force the ego to recognize there are aspects of the psyche it simply does not acknowledge (a part of this phenomenon was referred to by Poe as “the imp of the perverse,” for example). Individuation, then, is the process of achieving union with or acknowledgement of the unconscious.

To give a gameplay example, and this is something I’ve already mentioned a few times, it is altogether too easy to become too invested in one’s gameplay, and find extraction and disengagement from a game to be a difficult task. This is an example of the activation of the archetype symbolized by the ouroboros—the circle formed by a snake eating its own tail. The experience of game addiction, then, forces the player to recognize that there is more to one’s personality than that which is expressed in a game—in other words, that there is more to one’s psyche than just the aspect that the ego values.

Of course, the ouroboric archetype is not the only one experienced in gameplay, and those who have experienced flow will intuitively understand the idea of union with the unconscious. Thus it is my proposal here that, in providing a “safe” (in the Huizinga sense) mechanism for the activation of various archetypes, gameplay fundamentally promotes a deeper understanding of one’s psyche and is indeed a crystallization of the process of individuation.

Practical Considerations

All of this academic analysis is well and good, but of what practical use is it to a game designer? Mr. Johnson already made a rather similar (identical?) point, but if the designer can correctly identify the archetype which a game mechanic is manifesting, it becomes much easier to devise a narrative which provides a cohesive fit, and vice versa. As well, hopefully the above assessment can help in deepening the understanding of the player experience, and thus provide a more analytical foundation from which to evaluate whether or not a game is fun, or what works or doesn’t work in a game.

Footnotes

*One might question, then, what is the emergent personality of a game such as The Longest Journey or Syberia? This was actually brought up last week when I talked about how a psychological test can cause projection because the other of play is the perceived examiner who will “tally up” the test, so to speak, and supposedly gauge the subject’s intelligence.

**Case in point: a player just trying to pass a couple minutes may run a game of Solitaire without much investment at all—just enough to sort of want to win—so the interaction is barely an interaction at all, merely a click through of buttons and an examination of the results, as if one is browsing the web.

Works Cited

Edinger, Edward F. Ego and Archetype. Boston: Shambala, 1992.

Gray, Richard M. Archetypal Explorations. London: Routledge, 1996.

Jung Lexicon. Sharp, Daryl. 06 May 2005. CG Jung Page.

Playing and Gaming. Walther, Bo Kampmann. May 2003. International Journal of Computer Game Research.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like