Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What game design gems lurk in the unexplored nooks and crannies of the original 1996 Tomb Raider? With the franchise now rebooted, designer Hamish Todd takes a close look at the series' first game, and the possibilities its constrained platforming allowed.

March 1, 2013

Author: by Hamish Todd

What game design gems lurk in the unexplored nooks and crannies of the original 1996 Tomb Raider? With the franchise now rebooted, designer Hamish Todd takes a close look at the series' first game, and the possibilities its constrained platforming allowed.

The classic Tomb Raider games are some of the most commercially successful of all time. They were formative for many of today's gamers and game designers. They've become most famous for their varied texture work, and for the iconic Lara Croft, with her associated sex appeal. But, at the outset of the franchise, playing Tomb Raider wasn't about getting to know Lara Croft's character. It was about searching, shooting, and platforming -- mostly platforming.

I wanted to take a close look at the platforming challenges that classic Tomb Raiders offered us. I looked through their many levels, and I was surprised by what I noticed: all of the most eye-opening things were to be found in secret areas of the 1996 original. In this article I'll describe my more beautiful findings, and ask what makes them so fun.

To give you a reminder -- or an introduction! -- to the controls: Lara is a "tank," so with four buttons you turn her left and right, and move forward and backward. She can also jump and grab ledges.

Additionally, Lara can slide down slopes; when sliding, the only thing she can do is try to jump off the slope. This is not in the instruction manual. The first engagement I want to show you is a short challenge from the game's very beginning which introduces jumping from slopes.

Here, the eye is caught by a small, elevated alcove, and a squat, sloped block faced toward it. Getting into that alcove will be the first short-term success of the whole game -- it contains a health pickup.

Try to jump and grab the alcove's ledge, and you'll find it to be just out of your reach. Turn your attention to the sloped block behind you, the only other thing around. You've seen that it's slightly less elevated than the unattainable alcove ledge. You go over and jump up onto it... then you immediately, unexpectedly, slide down it and fall off, plopping you back at the front, facing the wall. This block is a bit of a troll -- it's the first mischievous piece of design of many we'll look at.

You'll be irritated but intrigued by that slide. You try doing it again, and you realize you can jump. After a few tries, you catch the ledge of the alcove, pull up, collect your prize.

This is a motivated, forgiving, uncluttered introduction of a semi-novel move; no textboxes required. A move that can be pretty exciting and, as you'll see, surprisingly deep.

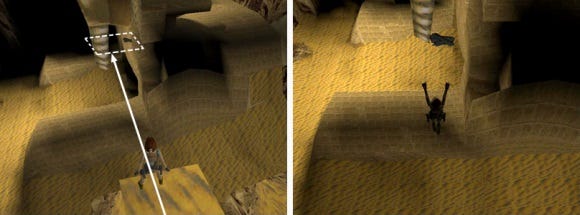

This is a rather fascinating challenge. Essentially it's about manipulating momentum.

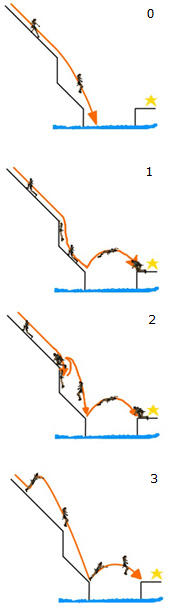

You enter this room on a slide (0). You're moving, and you can't do much about it. There's a secret on the opposite side of the room -- that's what you want. However you can't make it across by jumping or falling -- not from the top slope, which has brought you here.

You enter this room on a slide (0). You're moving, and you can't do much about it. There's a secret on the opposite side of the room -- that's what you want. However you can't make it across by jumping or falling -- not from the top slope, which has brought you here.

What you want to do is jump from that lower slope, but it's not clear how you can get to it. The top slide has given you a lot of momentum, which is causing you to fly over the lower slope, straight into the water. There are a few methods for getting to the secret, and all of them require the player to plan around the platforming controls.

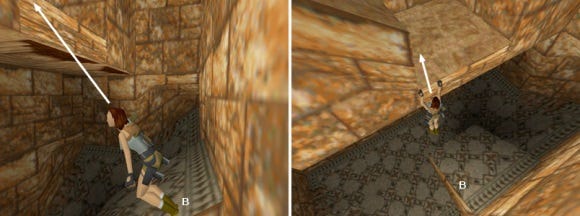

Here's one method (1). If you know what's at the end of the slope, you can send Lara down backwards, which allows her to grab the ledge when she falls off. Drop down to the lower slope, slide a little more, backflip at the last minute and you'll get to the secret.

But this is very unreliable. That final jump backwards needs to be bang on the end of the lower slope -- but you're sliding backwards! Knowing when to jump is guesswork. Getting to the secret this way is time-consuming and dull.

Here's an improved method (2). Catch the ledge of the upper slope, then pull back up onto it, then allow yourself to fall off again. Falling from a standing start, you get exactly the right amount of speed to take you directly to the end of the lower slope. It's nice that there's no timing involved in this method...

...but this third one seems the most elegant to me (3). It can be thought of this way: ordinarily when you fall off the top slope, your forward velocity causes you to sail over the lower slope before your downward velocity can get you to land on it, so you land in front of it. Our last method works by increasing your downward velocity while you're above the lower slope.

Bear in mind that as Lara falls, gravity increases her downward velocity. The longer she's been falling, the faster she falls -- this is true whether you've fallen off a ledge or if you're at the top of a jump arc. All this means that if you start a jump that peaks before the fall-off point, then by the time you get to the fall-off point you'll have gained more vertical velocity than if you had just fallen off, so you can get to the lower slope even though your forward velocity hasn't changed.

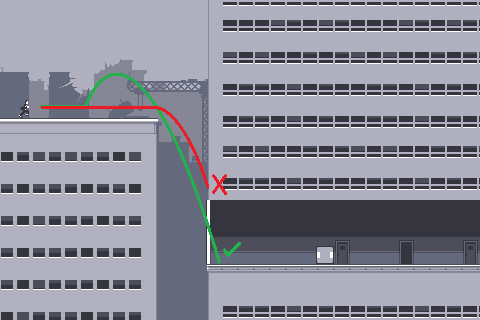

This strategy can sometimes be used in Canabalt to avoid hitting the sides of buildings...

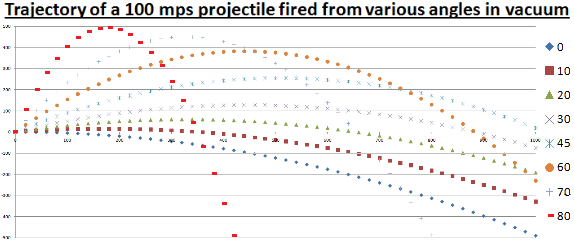

...and, I think, tells us something about real-world ballistics.

If you're doing a jump like this, you have to know your arc well and make sure it's not going to hit the corner. This is a fascinatingly unusual aim to have while doing a jump. It's also interesting because jumps are normally about changing your position, whereas here they're about changing your velocity.

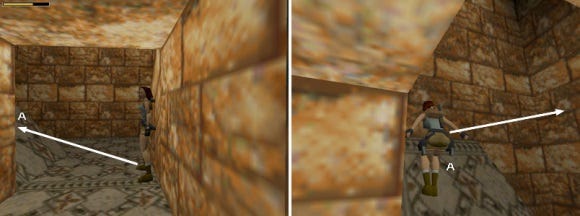

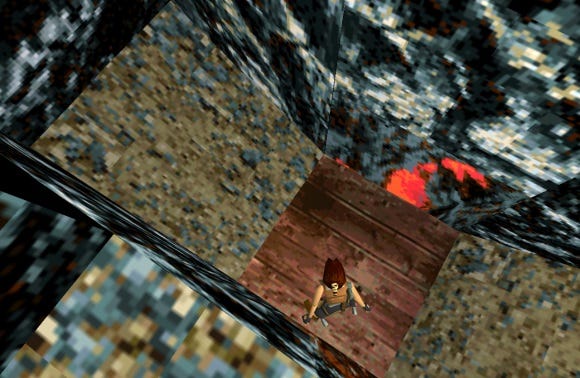

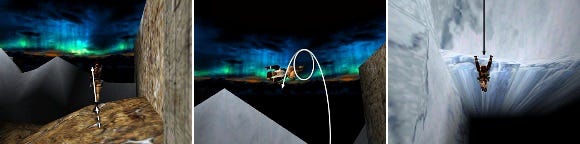

There is a very sophisticated three-jump sequence in this room. You go from the floor, to the slope on the lower right of this picture, to the slope in the middle, which you immediately spring off to grab the ledge above.

What makes this such a splendid engagement is a huge camera shift that takes place in the jump between the slopes. The camera rotates more than 180 degrees, and the two slopes rotate Lara by 270 degrees. Things move fast in this enclosed space; it's almost as disorientating as being flung through a portal. You have to make a plan.

One problem is that if your second jump is from the lower part of the slope, Lara will just end up banging her head on underside of the ledge. To be jumping from the correct part of the second slope, you have to jump from the correct part of the first slope. Your starting angle and location affect these; to work out what they should be, you must see through the rotation of Lara and the camera.

Note that all this was enabled by Tomb Raider's much-maligned automatic camera. It puts a strict limitation on you, motivating a creative approach. The same thing happens in a couple of the game's block puzzles.

By the way, look back at my picture of the room and notice the diamond-shaped slope in the far right corner. If you were to jump onto that it, you would witness an unabashed glitch in the slope-sliding. I don't think it was an accident that you could access that glitch in this room. By the end of this article I think you'll agree with me.

Some detail on the controls: the player can make Lara can jump in four directions, and she will jump without looking in the direction she is jumping in. The camera, which the player cannot control, likes to be behind her back during jumps.

Another thing: turning left and right is very slow. Everyone hates it. You can't really turn while running, and combat is quite messy and shallow because of this.

But again! Constraints can call for imaginative responses. The two constraints above complement one another in our next case study.

In this scene you have to get across a room on a bunch of collapsible platforms.

If you don't get off a platform before it collapses, you fall with it and you miss your chance to get a secret. There are five platforms. You go forward, left, forward, forward, right, forward.

This is one of the few places that forces you to use the sideways-flip. Turning through a right angle actually takes so long that jumping, then turning, then jumping again simply isn't an option.

On the first platform you have to jump forward, then sideflip -- anything more would take too much time.

All this takes planning and confidence. Once you've jumped forward onto that first platform, you can't see the platform to your left that you need to jump onto -- you just have to trust that you know the length of your jump arc. We usually get annoyed at cameras that don't always show us everything we need to see, but here it feels fair, because you've been given time to inspect the layout before moving -- a genuine piece of puzzle platforming.

The fairness is helped by the simplicity of the layout. From where you start your goal is straight ahead. And there are only five platforms, the minimum number that could force you to perform both a left and a rightward flip.

This is a similar trick in a nice upward spiral, with the time limit imposed by a closing door rather than fragile platforms.

Yet another "flaw" in the game that makes this sequence simpler is the unresponsiveness of the game's controls. While Lara is airborne, no button press will really affect her. This rigidity is rightly frowned upon by many developers -- it feels robotic, and can decrease depth. So, usually, platformers have air control and variable jump height. But rigidity has a few advantages! In these taxing jump sequences, airtime is a respite during which you can think about what to do next.

Speaking of rigidity, the next phenomenon I want to talk about is unique to the semi-responsive platformer.

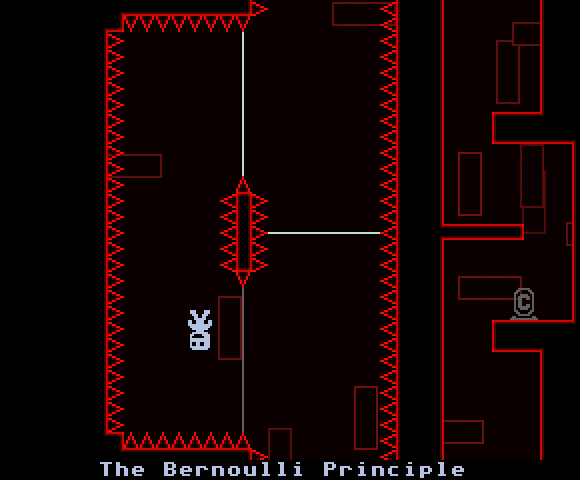

More control details: if the player holds down the jump button when Lara hits a slope, she springs off it automatically. There are three secrets in the game that require strange-looking sequences of automatic jumps. I think that strangeness is self-aware; in the two parts I'm about to talk about, it feels to me like the level designers are parodying the controls.

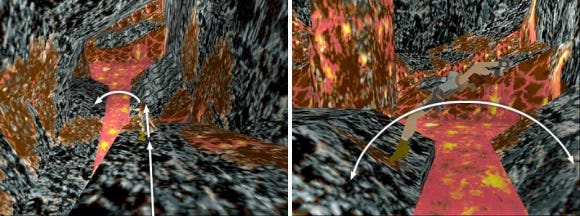

Here's the proposition: two slopes, faced toward one another. A single square in between - a wooden square (with glowing red rocks on either side of it -- this is a warning!) There's a room in the top left you want to get to, which means jumping from that wooden square. You approach the wooden surface, sliding down the slope toward it... but suddenly it opens! It was trapdoor with lava beneath it, lava that you're sliding straight towards!

Click here to see an animated .gif of this sequence.

Chances are you'll instinctively jump to avoid the pit, but that just takes you over to the other slope, which starts sliding you backwards into the pit again! You jump again, which takes you back to the first slope, and... so on. You just hold the jump button down, Lara hopping between the slopes, as you try to make sense of the situation. There really isn't much you can do -- it's a dangerous and inescapable scenario -- although it has such little input and it looks so ridiculous that it seems like a joke to me.

It's a joke with a punchline -- eventually the trapdoor just comes back up again (don't hold your breath waiting for this to happen in my gif, though). You may have difficulty believing your luck. When you dare to stop hopping back and forth and try setting foot on the wood, you find it to be perfectly stable. You go climb the ledge on the left and collect some riches. This all strikes me as so lovely, and so ridiculous: let's remind ourselves that these obstacles are supposed to have been put in place by baddies to thwart your efforts to move forward.

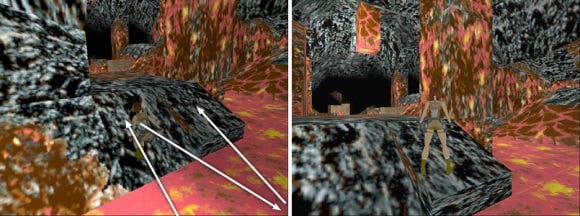

There is a good advancement of this idea in the Tomb Raider expansion Unfinished Business:

Here, a long slide will plop you down in a place where you must start jumping between two slopes. This time there's no trapdoor that'll come up to cover the lava. How do you get out of this? You might be hopping a while before you work it out, because while the solution is not complicated, it is unexpected.

Lara has the ability to defy physics somewhat, and change her direction while in midair. It's a very tiny change, so you may go the whole game without using it. Here, you're doing an awful lot of jumping, so slight changes can add up and eventually move you across the slopes to safety.

Again, to me, this all looks comical. You have to strategize while you're hopping back and forth like a cat on a hot tin roof. Infinite loops in their various forms are always the things that give "computeriness" away. These set pieces are my favorite of all, though they seem out of place in a "realistic" platformer where developers are trying to maintain suspension of disbelief and promote immersion. I actually think there must have been at least one person on the dev team who was happy to compromise immersion so they could play with the engine -- the last parts I want to talk about seem to me to be proof of this.

There are three extremely avant-garde parts of this game that ought to be better-known. These are three challenges that require you to make use of glitches in the mechanics.

First: in Tomb Raider fan communities, the "corner bug" is well known. When Lara jumps upward, she has a tiny movement forward. The collision detection when you do this seems to be a little sloppy, since doing it several times in a row can allow you to embed Lara in certain pieces of scenery. If she's embedded far enough, the engine will spit her out of there; the useful thing is that it spits her upwards, often further upwards than you can get by jumping.

Watch the above video. What an impish thing for a level designer to include!

This bug was kept in the engine all the way up to Tomb Raider 5. This is likely because the corner bug is the fan's best tool for exploring the levels beyond normal expectations. This was something the designers anticipated and felt like encouraging, so the bug stayed in.

Here's another medipak that can be glimpsed with a camera-intersection bug, and acquiring it highlights a scenery-intersection bug.

Here is the most brazen "bugged" set piece, from the same level as that second medipak. We have an invisible platform floating inside the space of a gigantic cavern, its existence only indicated by the coveted uzi clips perched on it.

If you can muster up the confidence, you can grab the platform's invisible ledge with a standard jump. You will then be scared shitless by some flying enemies who may well knock you off (the chances are that to kill them you'll use up those uzi clips you came here to get). If you manage to deal with them, you need to jump back to the cliff. So a new question arises: how do you dare set up a running jump on this surface when you can't see its boundaries?

We get a sweet example here of "old controls doing new tricks". To feel out the invisible boundaries, you can hold the "walk" button, which moves you slowly and stops you in places where the game detects ledges.

I have talked about most of my favorite parts of this game. They have these things in common:

The quality of the texture work is not up to the standard of the rest of the game

Structurally, they are all optional

Spatially, they are often sequestered away in small side rooms which contain only them

It's not that I like these features. It's just that these are features that the things I like seem to have. This leads me to believe that all these fun set pieces that were implemented towards the end of the game's development. I'll explain why I think that.

Planning and tweaking challenges involving the most intimate parts of platforming mechanics requires those mechanics to have been fully implemented. I think Tomb Raider's mechanics were being implemented almost all the way through development, because they were secondary to the visual design and texturing of the jaw-dropping locations. This is why, usually, you don't have to do anything very specific to move through the game's levels.

When the levels were almost finished and the mechanics had been fully implemented, someone on the dev team who had become intimately acquainted with the possibilities of the platforming had come up with some decent ideas. They knocked together the challenges I've talked about with basic textures, and slotted them into side rooms so they wouldn't get in the way of the nicer-looking level bits whose appearance had been painstakingly composed over many months.

These small challenges are now what we can look on as extremely modern pieces of platforming. Many of the movements I've talked about are short, and don't involve risking the loss of progress. The brevity lets you focus on the movements, and the forgiveness allows designers to surprise you. Surprise + Focus = Communication. Less like Prince of Persia or Mario, it puts me in mind of my favorite contemporary platformer, VVVVVV, a game which I feel communicates a lot.

Sadly, the sequels didn't really move any further in the direction of communication. The additions that were made to the game mechanics were vapid: the changes that grabbed headlines were that you could drive a few vehicles, and that you could use more guns.

They gave Lara new ways to move: monkey bars, zipwires, and ladders. These did enable the creation of new spaces, and also added to the "adventuring" feel of things. But there was never any nuance to interacting with them; mostly they are so slow they can feel like busywork. The worst example of slow busywork is crawling (introduced in Tomb Raider 3). Crawling is so dull. It's an insult to your intelligence, and mine. Cara Ellison believes that crawling was added mainly so that the player could get a good view of Lara's arse. I'm more inclined to blame the influence of Metal Gear Solid, but I definitely recommend this article of hers -- it will give your cynicism muscles a workout.

There was one addition that strikes me as thoughtful: a jump that allowed you turn 180 degrees in the air. This enabled the strategy seen above; it's interesting, though probably unintended, so I wouldn't really use it to defend the designers.

The original Tomb Raider was not entirely a good game, either. It's clear that the first priority with the gameplay was to show off animations and textures, the second priority was to make things humanly plausible. Depth wasn't really on the agenda. The developers looked at the platforming genre and decided that the most fun part was jumping from the very end of a ledge, and making it to the other side by the skin of your teeth. They animated that, and made some nice-looking locations for you to do it in. That was what they saw their job as being. The set pieces I've talked about were afterthoughts.

It would surprise me if the platforming of the new Tomb Raider offered anything cerebral at all. Its target audience are the fans of Uncharted and Enslaved. Those games are not about rewarding the contemplation of movement mechanics -- they are about rewarding obedience, and it frightens and upsets me that they are widely praised. Not that they are completely worthless pieces of media; they look and sound very nice. But I wish they would do away with the orwellian QTEs and meaningless walking around. I wish we could have more communication, and less crawling.

I'm indebted to the great Tomb Raider scholar Stella Lune for her consultation and for the use of several images.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like