Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The following is a condensed form of my master’s project, investigating early game levels/tutorials in video games to identify how to teach effectively. Analyzing participant response data to understand what affects player learning experiences.

The subject of my study was looking into learning in games, specifically the ability of a game to teach the necessary information about itself and to keep players engaged to continue with interest. I initially investigated the task of a designer, the issues with players and design of tutorials which led to George Fan’s GDC 2012 talk about his game, Plants vs Zombies.

Fan provided a great insight to the development of his game, focusing on his aims of making it accessible to play for all people, ‘casual’ audiences and notably his own mother. Fan’s presentation brought up 10 key points he suggested which could help improve game tutorials, but they lacked a psychological perspective, the behaviour and response of learners.

Querying Fan’s presentation, the master’s focus was refined, the project was set to research player experiences, investigate and identify the issues behind negative thoughts about game tutorials and early game levels and in comparison to identify why ‘good’ tutorials are successful.

By gathering data from a number of participants their answers can help identify reasons behind positive and negative experiences by looking through a psychological lens, uncovering how they are affected when being taught new information in a game.

The master’s project conducted a qualitative semi-structured interview process to help elicit the information required whilst taking steps to eliminate bias. The benefit of doing an interview was the ability to record the audio of the interviews, with the task of transcribing quotes and notes for the purpose of analyzing later on.

The following is the later part of the master’s in a condensed form, analysing the data received from the interviews.

Analysing the data

10 participants named ‘Participant A-J’ were successfully recorded in interviews answering 10 questions that would require them to provide games with early game levels/tutorials that they approved of and disapproved of, then to specify why.

Other questions were open ‘point of interest’ questions to help identify the participant’s personal preferences when learning in games; how much guidance, what causes disruption, how much to read...

With the data prepared, the analysis was started.

Following a 6 phase plan devised by Braun and Clarke, the method of thematic analysis was used to identify detailed descriptions with the data, which would then be used to help provide a clearer understanding for why people view certain tutorials positively and negatively.

“Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organises and describes your data set in (rich) detail.

…Thematic analysis differs from other analytic methods that seek to describe patterns across qualitative data – such as „thematic‟ discourse analysis, thematic decomposition analysis, IPA and grounded theory.” (Braun & Clarke, Using thematic analysis in psychology., 2006)

The process led to finding 26 initial codes in the participant response data, to start with they were seperated into 3 groups;

Positive Patterns

Doesn’t feel like a tutorial

Doesn’t disrupt game flow

Low chance of failing

Tutorial Boss

Preparedness

Ability to skip a tutorial

Freedom to experiment

Focus on unique mechanics

Negative Patterns

Hand - Holding

Not Skippable

Patronizing

Forced Videos/Cut scenes

Overload of information

Ruins game flow

Irrelevant Information

Failed to provide necessary information

Constant Pauses/Stops

Too long

These following patterns appeared in only the ‘point of interest questions’ data (Questions which were not specifically about positive and negative experiences).

Pop up messages

Unable to Skip Messages

Forced into games pace

Advanced information availability

Repetitive

Range of teaching levels

Short message preference

Tutorials are necessary

These codes are labels of themes that are prominent in the participant response data; the initial generation of identified codes would require a further identification, which led to a process of visualizing the codes.

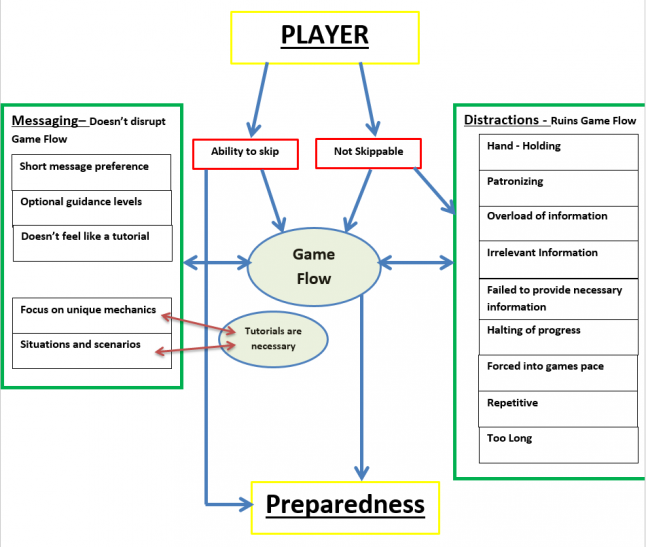

The application of ‘game flow’ as a core code to represent the player was incorporated where some codes signified the players learning experience, but it lacked the process of how a tutorial is conducted by a player.

Game flow being a loose term to explain psychologically how fully immersed a person is with a video game, for instance good immersion (good game flow) would lead to a loss of time perception and self-awareness because of the concentration with playing the game.

“It is easy to enter flow in games such as chess, tennis, or poker, because they have goals and rules that make it possible for the player to act without questioning what should be done, and how. For the duration of the game the player lives in a self-contained universe where everything is black and white.” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997)

However this leads to a theory with ‘preparedness’, if a game tutorial has provided a good teaching experience which doesn’t disrupt game flow, then the player would be prepared to play the game and in contrast if their game flow was disrupted, they will unlikely be prepared.

The ‘Preparedness’ label was taken from a code (which was changed to ‘Situations & Scenarios’) and promoted into a code to be treated as an end state for players in the learning process, leading to whether a player is prepared or not.

Other changes to the codes occurred during the analysis process; when reviewing the codes and their themes it was clear some codes were too similar to each other and were merged or dissolved to form more prominent codes.

The codes were appropriately forming into separate groups which developed a better understanding about the process of learning for a player, the justifications for each code by the participants were also providing a list of games.

After redefining themes and merging codes a final visualization diagram was produced, a flow chart diagram to showcase how the process of game flow work. When a player starts the game to engaging early game level/tutorials whilst dealing with ‘Distractions’.

All this leads to the ‘Preparedness’ of the player by the end of the tutorial/early levels, the amount they have learned and understand about the game will influence how prepared to properly engage the game they are playing.

‘Tutorials are necessary’ is a sub theme, a realization by participants who came to accept that some aspects of the game they played were necessarily required to have a tutorial to help explain specific information. Whilst it doesn’t always apply, the fact that it is always possible to happen justifies to keep its presence.

Following the analysis of the participant response data, five final themes of ‘Good game flow’ remained after reviewing, dissolving and merging codes. Per the findings of the analysis, ‘Good game flow’ provides the optimal learning experience so as long as distractions are prevented from intruding and are controlled.

The final focus is to now perform a final analysis of each of these ‘Good game flow’ themes through a psychological lens, to explain the process in these supported themes of good game flow and the reasons why ‘Distractions’ can ruin the learning experience.

This theme generated from one of the questions in the interview process, ‘When learning in games, how much do you prefer to read?’

This question was conceived from George Fan presentation (Fan, 2012) tip called ‘Use Fewer Words’, it was first queried back in CT7PCODE when trying to understand the basis behind what Fan was trying to explain.

Fan simply explained his rule for using no more than 8 words a sentence, to improve people’s ability to understand what’s being said. A look into explanations of brevity and readability formula only provided evidence to prove whether a written piece of text is difficult to read or not.

This led to including the previously mentioned question into the interview, the aim to acquire the insight of participants and what they preferred. The results proved the most prominent answer was short messages, participants expressed that they prefer, for instance what Participant C said about instructions;

“Initially needs to be short, concise and give a general idea of what needs to be done in the level and allow the player to experiment... “

This example perfectly portrays the overall popular answer given by the participants; players want information given to them in an effective and efficient manner. In contrast reasons that affected their learning experience was also similar, Participant F explained their preferences and reasons;

“A detailed paragraph in the case of a new item because a sentence or 2 may be not enough but the whole text on a screen may be too much for you to digest and understand what’s been required then, so I’d say a detailed paragraph to explain the uses of something so then they got a good idea of how it works and you could potentially use it.”

This can relate to focus and attention, wherein a person is processing information in a task.

Not everyone is freely capable to read large blocks of text without the issue of losing focus,

Participant I made note of this by saying, “Large chunks of text ‘takes you out of the moment’”.

A bombardment of information, this can use quite a lot of cognitive effort for people, making them anxious or distracted and ruining their learning experience. Worse yet the participants mentioned their dislike for the inability to skip messages, so if a game badly presents new information that they may not need, the player will be forced to read it or lose focus in the game.

Daniel Kahneman theorized a very relevant scenario when elaborating his explanation of attention and effort;

“…the schoolboy who pays attention is not merely wide awake, activated by his teacher's voice. He is performing work, expending his limited resources, and the more attention he pays, the harder he works. The example suggests that the intensive aspect of attention corresponds to effort rather than to mere wakefulness. In its physiological manifestations effort is a special case of arousal, but there is a difference between effort and other varieties of arousal, such as those produced by drugs or by loud noises: the effort that a subject invests at anyone time corresponds to what he is doing, rather than to what is happening to him” (Kahneman, 1973)

To listen and perform is work for a learner and this specifically will occur during early games levels/tutorials that are aiming to teach them, so they must be carefully designed in providing this new information to them. Word amount must be used efficiently to help maintain a player’s attention and word usage being respectful to the player to prevent irrelevant information from patronizing or misinforming them.

Attention is what allows us the ability to selectively process but people are still susceptible to distraction by other forms, this alludes to working memory load; for example games provide many sensory stimuli both visually and audibly;

“Moreover, in a dual-task setting, high working memory load sometimes makes a separate, concurrent task more susceptible to distraction from irrelevant information and sometimes less susceptible depending on the relation between the task material and distracting material.” (Sörqvist, Stenfelt, & Rönnberg, 2012)

Therefore after assessing what the participant data provided, reviewing their preferences and the issues they had, a conclusion can be understood behind Fan’s ‘Use Fewer Words’ tip.

By properly maintaining the presentation of written information player attention won’t falter. Certain factors such as effort required in reading and understanding the terminology will have to be reviewed, considering target audience should be its biggest influence but with newcomers in mind as well.

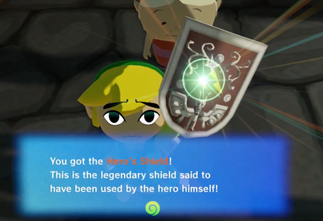

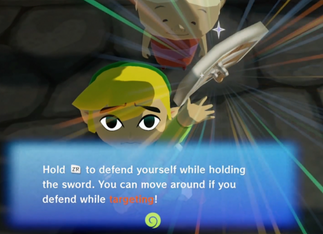

One notable example of a game that manages to provide the optimal method in providing written information to players was Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker (Nintendo EAD, 2002). Suggested by Participant A, throughout the game it provides written information about interactivity, new items and weapons in a discreet manner.

Nothing forces the player to interact with items early on; the game provides unobtrusive prompts throughout to help inform the player what button to press to engage with items it they get up close.

Participant A made a note that when a player retrieves a new item.

‘Where when an item is found it will give a brief explanation for what it does and that’s it, from that basic instruction it’s up to the player to figure out the rest. Quick, easy to read, skippable text.’

Aiming to improve player enjoyment should bring the benefit of improved attention; this was mentioned by literacy and learning researcher, James Paul Gee. He was inspired by helping his six year old son with a game Gee started an analysis and created a list of learning principles from good games; In relevance was one of the principles from his analysis - Information ‘On Demand’ and ‘Just in Time’.

“Principle: Human beings are quite poor at using verbal information (i.e. words) when given lots of it out of context and before they can see how it applies in actual situations. They use verbal information best when it is given ‘just in time’ (when they can put it to use) and ‘on demand’ (when they feel they need it).” (Gee, Good Video Games and Good Learning: Collected Essays on Video Games, Learning and Literacy, 2007)

Short message preference contributes to the optimal learning experience by preventing; large blocks of text from interfering in a player’s attention, maintaining visuals and auditory stimuli to prevent loss of focus and granting the player the ability to skip text. Therefore, the effectiveness of Fan’s 8 word rule can be understood with the context of how reading affects a player and why early levels/tutorials should accommodate.

One of the key points suggested during the research corpus in CT7PCODE was a designer’s dilemma.

The issue being that the game necessarily needs to teach players about what it is, how to play it and preparing them for the actual game, in parallel the process needs to keep the players invested and engaged.

Participants expressed their positivity about being taught about the game, but not with the sense of knowing they were being taught, for example Participant J’s response in regards to the start of Skyrim (Bethesda Game Studios, 2011);

“It throws you straight into the action so that you’re not stuck in a condescending train exercises, you are faced straight up with a dragon and you are taught via one person who gives you dialogue as opposed to/ as well as on screen pop ups, so if you missed the dialogue you can still read ‘press A to do this’, ‘press trigger to shoot with a bow‘.

“It throws you straight into the action so that you’re not stuck in a condescending train exercises, you are faced straight up with a dragon and you are taught via one person who gives you dialogue as opposed to/ as well as on screen pop ups, so if you missed the dialogue you can still read ‘press A to do this’, ‘press trigger to shoot with a bow‘.

Learning under direct instruction can be an issue to control, although Participant J clearly describes how it can be performed appropriately. Specifically with Skyrim, the dialogue coincides when engaging action in real time, by searching for loot, equipping armour and weapons and engaging in combat – all in the aim of getting the player accustomed to the gameplay.

Does that mean the learning process happens through an experience?

A look into the behavioural perspective should provide some insight;

“According to the behaviorists, learning can be defined as the relatively permanent change in behavior brought about as a result of experience or practice…

… The focus of the behavioral approach is on how the environment impacts overt behaviour”. (Huitt & Hummel, 2006)

Behavioural learning theories categorize differently but here is a general observation;

Early game levels/tutorials can provide stimulating experiences with action based events, much like what happened with the Skyrim experience.

The events that take place will ‘condition’ the player, they will learn from their own actions (overt behaviour) and apply that to future events within the game.

There can potentially be other ways in understanding how a game can teach; implicit learning was queried back in CT7PCODE as a potential answer behind learning, in a manner of non-intentional learning - compared to instructional external learning ;

“…the ability to adapt to environmental constraints–to learn–in the absence of any knowledge about how the adaptation is achieved. Implicit learning–laxly defined as learning without awareness–is seemingly ubiquitous in everyday life.” (Frensch & Rünger, 2003)

Whilst there are similarities to behavioural learning theories, implicit learning branches from cognitive psychology, the rational thinking and mental processes of the human mind.

“…implicit learning is taken to be an elementary ability of cognitive systems to extract the structure existing in the environment, regardless of their intention to do so.” (Jiménez, 2003)

However, during the analysis of this project participants have expressed the problems they have with games that teach in this manner, specifically such issues as halting of progress which consists of several negative distractions.

It is based on 4 preliminarily themes;

Pop up messages

Unable to Skip Messages

Constant Pauses/Stops

Forced Videos/Cut scenes

Participants expressed their annoyance with these specific themes would disrupt the flow of their game, ultimately ‘halting their progress’, Participant I provided a well-rounded explanation;

“If they go on for too long or the main one for me is ‘very stop-starty’ where they will tell you that you need to do something and then when you do it will immediately stop and then bring up another bunch of text saying ‘well done here’s the next thing’ and then put you back into the game, just let it flow.”

This process occurs in another manner, the distraction theme defined as ‘Hand-Holding’, but to explain what this phenomenon is would require several instances of what the participants have said. It was mentioned numerous times in the interview process, when most participants would happily use the term ‘Hand-Holding’ as it was a general term, so with use of follow up questions they were asked to provide their definitions.

Participant E held a negative opinion in regards to hand-holding and how they were treated;

“It’s when a game barely gives you any time to move or explore in your own leisure to find out things and forces you to do it one way.”

Participant G gave a more literal explanation as to what hand-holding is;

“Where a game takes control away from the player in order to teach them something, so it will disable all the other buttons except the one you’re meantto press at that moment.”

Furthermore, there was a lengthy response by Participant A when describing the reasons behind their choice of level ‘1-1’ in Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo R&D4, 1985) as a positive experience. They outright provide an interesting personal analysis, potentially revealing how this game provides one of the greatest examples of ‘Doesn’t feel like a tutorial’, but then also provided their analysis of ‘hand-holding’ when queried with a follow up question.

“The fact that it didn’t feel like a tutorial. The fact that it didn’t give you any ‘hand holding’ instructions such as a message popping up on the screen telling ‘you must press the A button to jump’. Instead the game lets you figure that out for yourself by putting you in a situation where you are in no harm if you try to experiment with the controls.”

Follow-up question: What do you consider ‘Hand holding’?

“A position where the game puts you in a no fail state in order for you to specifically learn the controls, it’s sort of in a limbo from the rest of the game, where you have the game and it takes you away into this ‘little arena’ or a ‘bubble’. Where it’s just ‘Ok now we’re going to teach you how to play the game’, whereas you could have just dropped me in the beginning area and let me figure it out myself as I go along. So in that way people who already know the controls can just get on with it, as opposed to being forced into a mandatory tutorial.“

The designers of the game, Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka participated in an interview about the creation of the first level, Miyamoto explained that;

“…we wanted the player to gradually and naturally understand what they’re doing. The first course was designed for that purpose. So that they can learn what the game is all about. But then after that, we want them to play more freely. That’s the approach we’ve taken with all of the games that we make” (Eurogamer, 2015)

In observation of the game, the utilization of level design to teach players in the environment encouraged players to explore, realising the actions and adapting to changes – relates to the theories of learning and memory.

“Memory is a major area of study for cognitive psychologists. Memory is the way in which we encode, store and retrieve information. Encoding is the process in which information is transformed into memory.” (Yeomans & Arnold, 2013)

Reviewing what the participants have said, it is clear that the addressed issues are clear examples of breaching a player’s state of flow, which was explained earlier in the analysis. The perfect example of disrupting a player’s immersive state in the game by stopping them unnecessarily, not allowing them to skip the unneeded information/videos and being too overbearing in trying to teach them.

“Good game designers are practical theoreticians of learning, since what makes games deep is that players are exercising their learning muscles, though often without knowing it and without having to pay overt attention to the matter.” (Gee, Learning by Design: Games as Learning Machines, 2004)

In terms of an optimal learning experience, what better way to teach than to putting players in an immediate situation, the actions and events can maintain a player’s attention to help them learn and adapt. Through the effect of memory a player can recall from earlier experiences and apply it to navigation and problem-solving in the later parts of the game, a good state of ‘Preparedness’.

One of the main focal points with early game levels/tutorials is to provide enough information about the unique mechanics that appear in the game. Game mechanics that provide a completely new style of play to a genre will require extra effort in teaching players, Participant D gave a relevant insight with their experience of the Call of Duty Franchise;

Notes based from the interview put to detail how the participant didn’t consider there being any major changes to the series of games until Black Ops 3 implemented ‘Exo Suits’.

Participant D expressed how beforehand all a player would need to prepare for in a Call of Duty game was to learn how to shoot and engage, but with a new unique mechanic they considered it was necessary for added guidance on this new integral mechanic, ‘necessary learning’.

Necessary learning however requires maintenance when teaching, the preferred design options that have been reviewed from the participant data show that an overbearing approach to teaching can disrupt their engagement early on. Referring back to hand-holding again, it causes disruption to the game flow due to a heavy interest in the unique mechanics that are being taught but its stripping away the players freedom to learn at their own pace.

Participant B made note that if a player can’t play the game at the pace of their choosing, it can cause a negative reaction. Furthermore if they manage to understand the new information quickly but the game doesn’t match the speed of their progress, especially with the likes of a returning player, then it can end up being ‘a chore to work through’.

Providing another perspective, the scenarios of an experienced player playing early game levels/tutorials can easily lead to patronization because they already know what to do/how the mechanics work. Activities that help teach but can be accessible to the experienced player as well, in reminiscent of the George Fan’s tip ‘Just get the player to do it once’, the literal idea that a player only needs to succeed once to understand.

“Sometimes, players can pick up on mechanics after performing an action just one time. “Once they see the results of their action, that's often all it takes for them to understand that action," Fan said.” (Fan, 2012)

Fan goes on to speak about how indication can be used to direct players and encourage them to engage specific items or actions, which would as stated by Fan be enough to teach the player.

Participant C provided an in-depth experience they had with Megaman X (Capcom, 1993), in focus about how the game’s first level had taught them by indicating and encouraging;

“It taught you everything about the game without actually going through a tutorial section. The first level of the game, where what it did instead of explaining everything where as you started the game it just threw you into a scene and because the game only used the controller you then just had to press buttons to try and work it out.

So you went left, right, up, down for movement and then as a 2D platformer, as you moved across the stage it just drops you through the floor and you were just left in a pit with nowhere to go.

So you just ended up walking around trying to figure out what happened and what you were actually supposed to do was wall jump all the way up to the top by jumping on the wall and doing it but it’s just throwing you in as an experiment and then you have to work it out yourself but it teaches you about that important mechanic that you will use later in the game.

Now naturally when you see an enemy you think press the shoot button because there’s no way to jump over the enemy so the only way is to shoot, so you learn the shoot button through that, movement comes naturally as you have to go somewhere and the jump button on top of the wall jump you learn as you fall through the pit.”

“Most of the game is mostly trial and error through learning, hence there’s not actually much in essence it almost treats mechanics like a puzzle game than an actual tutorial. Where you have to work it out by playing the game, however the way they teach, whether it be the story or the game mechanics is through puzzles in which you have to use that specific mechanic to do so.”

Follow up question - Was there anything else that made you possibly understand to approach situations?

“There is a particular enemy where a shield will pop up out in front of them and as you shoot it obviously won’t do any damage and then they put away the shield and your able to shoot them and what that also teaches you for that enemy is that when they go into a certain animation they might be invulnerable or have different properties and to expect something new.

I feel like that is also done in a way where bosses have multiple stages, the first boss has a start up stage where it attacks you in another way and then a pattern in the next one, but the thing is you didn’t actually have to win that battle since you were supposed to lose when you got to the end you weren’t able to do proper damage to the enemy and then an ally character came in and saved you with a certain ability, you then pick up that ability later on in the game and can use that against the boss in order to defeat them later.”

The player discussed and mentioned many points of the game that helped them learn in the theme of being ‘thrown into action’ and stimulating the process of trial and error.

The level provided scenarios in which all the core mechanics of movements, jumping and enemy behaviour is addressed to the player and exposed them to go through the motions and prepare them for what entails in the actual game.

This scenario of learning relates strongly to Fan’s ‘Just get the player to do it once’ tip, but what exactly causes this effect?

An investigation of familiarity within psychology led to a clearer view of how people gain an understanding.

“Usually, high fluency is associated with a positive or safe state of the environment in which information is effortlessly processed and not interrupted by obstacles or problematic events, whereas low fluency indicates that something is wrong. Over time, a link between fluency and affect may have developed so that processing ease may immediately feel good, whereas processing difficulty feels bad.

Fluency can account for the mere exposure effect because familiarity is an important moderator of perceptual as well as processing fluency. Familiar stimuli are processed faster than novel stimuli, elicit less attentional orienting, and produce less of a mismatch with existing memories, all of which result in the experience of higher processing fluency.” (Gillebaart, Förster, & Rotteveel, 2012)

Process fluency can be used to review how a player processes new information, the scenarios used in Megaman X for instance was favoured a lot more by Participant C for instance, more positively compared to a hand-holding scenario. Exposing the player into a scenario, encouraging them to succeed in doing the task once can fulfil the stimuli in a players learning process, so when they need to perform the tasks again later on they should have less trouble remembering how to perform properly.

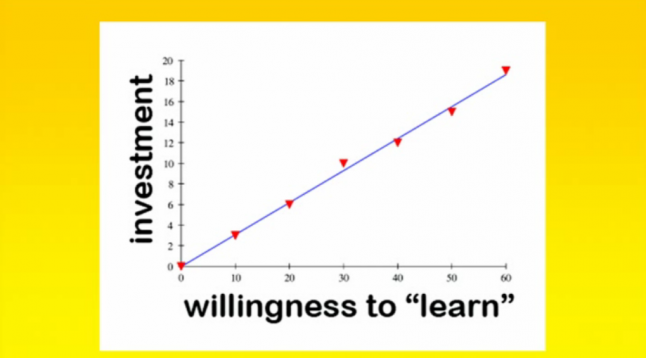

George Fan’s presentation made a significant point about the concept of a player’s ‘willingness to learn’, the varying levels of understanding and the capabilities of the player learning.

"When I first start playing, I only have a certain willingness to learn things. But as I play it and become invested in the game, I have more of a willingness to learn."

A range of teaching levels needs to be considered and established because not all players will have a complete understanding of the game they’re playing immediately.

If a new player were to be expected to learn advanced knowledge immediately then they will most likely be overwhelmed causing distractions and indecision such as stress and anxiety leading to a negative response in regard to what they are playing.

Participant H dealt with this issue after having to deal with the difficulty in understanding a game called Chromehounds (FromSoftware, 2006);

“As a game as a whole I quite enjoyed it, but regarding early game levels/tutorials it was poor, it was incredibly hard to get my mind around that learning curve because it was a mecha game and there was a lot of information it wasn’t telling you. For me to play the game for a couple of hours I did pick up a things eventually but I really wish there was a sense of ‘do this, this is because of this’.”

During the analysis ‘Overload of Information’ was addressed as the antithesis/main obstacle for the ‘Willingness to learn’ concept, its relative psychology term being information overload. In relation to attention and focus from ‘Short message preference’, Information overload has been addressed in relatable literature in regards to how disruptive it can be during the learning process.

“Attention is poor when you are either understimulated or overstimulated. Attention is best when your level of stimulation is just right. Psychologists use the term “arousal level” to describe how bored or excited you feel. It is a physiological term that corresponds to how much or how little adrenaline is pumping through your system. The amount of adrenaline, in turn, depends on how bored or excited you feel. Arousal is also called activation or drive.” (Palladino, 2011)

Palladino further explains the overwhelming feeling which the distraction theme ‘Overload of information’ encompasses; due to overstimulation/high amount of effort a person who has limited attention will become stressed;

“When you’re overstimulated and your adrenaline level is too high, you’re in overdrive. Depending on your thoughts and situation, you might feel intense, overexcited, worried, nervous, angry, or afraid.”

However not all stress is negative, rather it is subjective to demands and tasks, eustress is defined as positive stress and is the counterpart to distress (negative stress) in which both relate to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s flow theory.

As mentioned previously, flow is the engaged state of immersion when a person is taking part in an activity, depending whether they are using their full attention or not can be affected under circumstances.

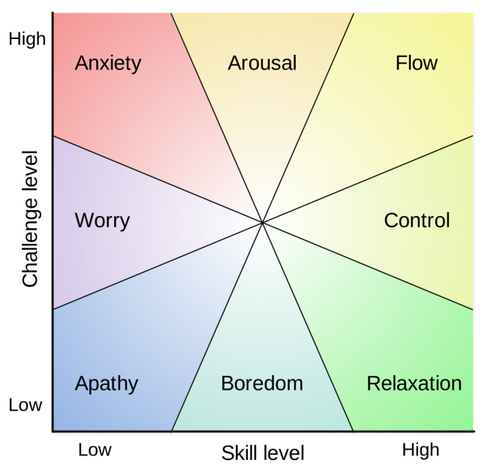

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi gave a TED talk and provided a representative graph scheme of flow channel to measure the challenge a person engages in relation to their current skill level at the time (pictured right). (TED, 2008)

In regards to achieving the state of flow,

“…it will be when your challenges are higher than average and your skills are higher than average. And you may be doing things very differently from other people, but for everyone that flow channel, that area there, will be when you are doing what you really like to do – play the piano, be with your best friend, perhaps work if work is what provides flow for you.

And then the other areas become less and less positive. Arousal is still good because you are over challenged there. Your skills are not quite as high as they should be, but you can move into flow fairly easily by just developing a little more skill.

So, arousal is the area where most people learn from, because they’re pushed beyond their comfort zone and to enter that –going back to flow – then they develop higher skills.

Control is also a good place to be, because there you feel comfortable, but not very excited. It’s not very challenging any more. And if you want to enter flow from control, you have to increase your challenges. So those two are ideal and complementary areas from which flow is easy to go into.”

Managing the guidance levels within a game can contribute to the ideal optimal learning experience, the challenges have to progress in a manageable difficulty to help increase the player’s skill.

A process of teaching skill and helping a player improving it will have to be designed to monitor the player, to prevent them from slipping out of the optimal experience, their gameplay experience; otherwise they will likely become anxious or bored.

For teaching, incremental accretion is a method that can help keep a player in a focused state. By providing tasks incrementally a player can gradually improve their newfound skills and knowledge by putting them to slightly harder tasks and steadily climb the difficulty curve and become more experienced with the game.

Much like the issue Participant H had with the learning curve in their chosen game, they struggled to understand what to do, due to the hardship of the tasks the game gave them and wasn’t provided the right information or indication.

Chris Crawford’s book on game design explains the expectations of a player, “…they like to know that they are on the right track toward accomplishing that goal.

The best way to do this is to provide numerous sub-goals along the way, which are communicated to players just as clearly as the main goal. Players are rewarded for achieving these sub-goals just as they are for the main goal, but with a proportionally smaller reward. Of course one can take this down to any level of detail, with the sub-goals having sub-sub-goals and so forth, as much as is necessary to clue players in that they are on the right track.” (Crawford, 2003)

The incremental approach coincides well with the willingness to learn concept, the more time a player invests into the game through a process of iterative tasks of increasing skill, the more willing they will be to learn more advanced knowledge and partake harder challenges.

Mastery of a subject will never be immediate, pace will vary among people, this why the ‘range of levels’ theme was considered and eventually formed into ‘Optional guidance levels’. A player should have a choice of the guidance level the game provides but shouldn’t be stopped from also pursuing advanced knowledge

Participant C made suggestions in regards to this theme with competitive fighting games in mind. Providing an insight of the experienced player engaging a game, they thought it was fine to provide the in-depth knowledge so as long as the player has gained enough experience and also be allowed to look for further knowledge when they are willing.

As established, the more experienced a player is the less issue they will have with learning new skills and knowledge; this refers back to cognitive theory based on effort used in the learning process,

“In summary, when a complex intellectual skill is first acquired, it may be usable only by devoting considerable cognitive effort to the process. With time and practice, the skill may become automatic to the point where it may require minimal thought for its operation. It is only then that intellectual performance can attain its full potential.” (Sweller, 1994)

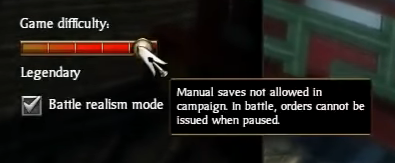

Participant C also provided a very interesting in depth response about a series of games they played, the Total War series (Creative Assembly, 2000), they made note how this series is a perfect example in how to offer optional guidance levels.

Image references will be taken from Total War: Shogun 2 (Creative Assembly, 2011);

In this top down strategy game there are options to how much advice you receive, from a high amount of advice (what you should do each turn), to medium (a general idea of where to go) or simply none.

You have the ability to change the settings during the game, “because even at higher difficulties it might not be as relevant but even at medium when you’re learning the game it’s important to have the right amount of advice while being able to switch it off if it’s getting too easy or if you already know it”.

“I feel as long as the initial tutorial needs to not feel like an arduous process that’s just teaching you the general buttons in a game. I feel like you should be able to go back and then find ‘in depthness’ about the tutorial after it happens, so fighting games when you got long combos to learn having a section which teaches you that, such as street fighter, if you want to go find it that’s good but it shouldn’t be the moment you load the game to get through about 20 different tutorial levels before your even allowed to play your friends, for example.”

Reviewing what Participant C said about this type of game, it is clear that it has an extensive amount of information to teach to the player based on management and real time strategy. The game relies upon explicit instructions for the extensive help, but it’s a matter of how it manages to do so and follows up on the given information.

Referring back again to James Paul Gee’s principle - Information ‘On Demand’ and ‘Just in Time’.

“…Players don’t need to read a manual to start, but can use the manual as a reference after they have played a while and the game has already made much of the verbal information in the manual concrete through the player’s experiences in the game.“ (Gee, 2007)

This quote supports what Participant C said, Total War provides varied levels of help to the player’s choice and even the most extensive help option appropriately manages to present new information in a helpful manner. The game possesses an in game encyclopaedia with a whole glossary of information based on all the intricate details of combat, tactics, units and more.

This is not forced upon the player; rather it instead is always available to a player who wishes to seek further knowledge and more willing to learn about the game at their own pace.

In relation to the focus of mechanics, the method of how they should be taught is a factor in teaching people that can help improve the engagement of players. Strongly relating the Fan’s tip of ‘Better to have the player ‘do’ rather than ‘read’’, where Fan explained that "The best way for a player to learn is to actually perform actions in the game".

This tip was previously queried and was adapted into another point of interest question, but it didn’t focus the reasons behind why players prefer to do instead of read.

However the interview process still revealed participant preferences and opinions that have been reviewed and progressed into forming this theme that contributes to good game flow, ‘Situations and scenarios’.

This theme had a few codes dissolved into it, to further justify its definition and relation to early game levels/tutorials, one particular participant can provide a perfect example to showcase what this theme encompasses.

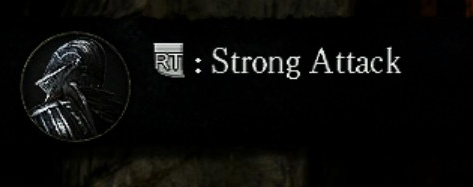

Participant B greatly appreciated how Dark Souls (FromSoftware, 2011) taught players with its starting area called ‘Undead Asylum’. The participant went on to describe how a player can start with no knowledge of the game but manages to keep them engaged to complete this area more than prepared.

“The game doesn’t directly pause any of the game flow in order to teach you any of the mechanics, what it does is it places these readable signs on the ground, that don’t pause the game but still tell you with a little heads up text box for what different moves do.”

“If at any point you dive in, you respawn at a fairly recent part of the level where you can try that section again in a fairly short amount of time so it’s not like there is a lot of delay between attempts to learn. It preps you up for a boss battle which is a good introduction to the game flow and hitboxes in general because it’s quite a large enemy so you’ll have to get used to spacing fairly early on as it does with the regular enemies in the game”.

Follow-up question: Would you consider the boss battle practice?

“It is definitely practice; if you go a certain route they intentionally give you an advantage in the battle with a special attack that makes the boss start with a lot less health, so it makes it a lot easier to attempt rather than going the normal way.

The participant expressed a great amount during the interview, the game was investigated further to better understand the participant’s key points that they made.

Three codes that appeared during the analysis; ‘Low chance of failing’, ‘Freedom to experiment’ and ‘Tutorial boss’.

These were identified in the participant’s insight of Dark Souls and it’s a good opportunity to help elaborate how these three codes link as ‘Situations and scenarios’.

Low chance of failing -

During the very start the player is met with some messages on the floor that can be interacted with for tips if chosen.

The floor messages will prompt the player the right button to perform a strong attack against an enemy that will not attack back; you can learn how to attack without the worry of making a mistake or having to deal with the risk of death.

The player will clearly see how their stamina bar will drain after each attack and see numbers appear above the enemy, the damage taken.

Tutorial Boss -

This starting area has a set goal in defeating a boss, ‘Asylum Demon’, but the game forcibly will put a player in a losing scenario to force them to further explore and learn around the level.

In the interview the participant proceeded to further explain how the game provided situations they had to identify, endure and utilize;

How traps can occur when traversing a level (for instance the stairs), but by surveying the aftermath of such an event a player can find new areas to explore (in this case they are rewarded some items that are require to progress further).

Made note of how the area is designed to be played multiple times, providing new players the chance to explore and understand more and experienced players to navigate without issue.

The level ultimately leads to providing an alternative route to engage the boss and showcasing the use of a new plunging attack that can deal a lot more damage in the effort to defeat it, by allowing them to perform it themselves.

The game promotes the idea of not worrying about risks and exploration by rewarding the player with a much better opportunity to defeat the boss.

The game promotes the idea of not worrying about risks and exploration by rewarding the player with a much better opportunity to defeat the boss.

Freedom to experiment –

Thanks to the utilization of the mechanic of bonfires a player may fail during this area many times, but as stated by participant B,

“…you respawn at a fairly recent part of the level where you can try that section again in a fairly short amount of time…”

One particular section after evading the boss monster has a bonfire set up right when a player needs to learn how to utilize a shield. A second bonfire is placed nearby a narrow corridor section where an archer enemy will continuously shoot arrows; a player who keeps running forward will die.

The players needs to loot a corpse that’s slumped near area of shelter, then the player can grab a shield and easily run down the corridor blocking arrows.

No instruction is given to the player, they will either learn how to properly approach this enemy by interacting with whatever is around them or die and return to the bonfire located just outside of the corridor. By being put into this situation, a player isn’t being dragged along or ordered to fulfil tasks but rather the tools were placed around them and they had to figure it out themselves with their own decisions. Mistakes will be made, but its situated that a player doesn’t suffer if they fail.

“Good video games lower the consequences of failure; players can start from the last-saved game when they fail. Players are thereby encouraged to take risks, explore, and try new things. In fact, in a game, failure is a good thing. Facing a “boss” (that is, a new level of problems), the player uses initial failures as ways to find the boss’s pattern and to gain feedback about the progress being made” (Gee, Good Video Games and Good Learning, 2005)

The apprehension of knowledge in this area known as ‘Undead Asylum’ is effective, by transferring the right information and knowledge to the player without the need for a direct approach of instruction. The level design perfectly puts players into situations where they can figure out how to progress with what they believe is their own choice, even though the level was designed in such a way to prepare them.

It encouraged players to develop a growth mindset, following the principles that to succeed; the learner must put in the effort and persist, they must challenge themselves and if mistakes are made they will learn from them.

“The passion for stretching yourself and sticking to it, even (or especially) when it’s not going well, is the hallmark of the growth mindset. This is the mindset that allows people to thrive during some of the most challenging times in their lives.” (Dweck, 2006)

To learn through experiences Dark souls continues to increase the challenge, the amount of surprises and the amount of information a player must acquire to keep the learning process engaging. ‘Better to have the player ‘do’ rather than ‘read’ is a very relatable tip to how this game teaches but why would participants prefer engaging an activity over reading/taking instructions and repeating what was asked?

An article written about retrieval based learning by Jeffrey Karpicke explains how people actively reconstruct knowledge based upon what they are presently engaging, what available cues.

“People instead have the ability to use the past to meet the demands of the present by reconstructing knowledge rather than reproducing it exactly.” (Karpicke, 2012)

Karpicke conducted an experiment with college students to study educational texts but in three different approaches conditions to learn, to see if repeatedly reading text is better off than engaging in retrieval. The results led to show that the students who practiced retrieval better retained the knowledge.

“We have already seen that active retrieval enhances learning of meaningful educational materials and that these effects are long-lasting, not short-lived. Recent research has shown that practicing active retrieval enhances performance as measured on meaningful assessments of learning and that these effects can be greater than those produced by other active-learning strategies.” (Karpicke, 2012)

By working with memory, retrieval can help keep a player informed and prepared by using activities to keep reconstructing their knowledge and learning how to engage new situations, much like what happens in Dark Souls from start to finish.

Plans for this project initially had plans to utilize the findings from this project and apply it to a newly developed game but as time progressed the idea became unrealistic. My own capabilities and skills wouldn’t have sufficed to create a solo project either in terms of feasibility or with the time constraints.

Although my project wasn’t applied to a newly produced game, this study has produced indications and guidelines that can aid future research. Hopefully the findings from this project can contribute to helping designers create more effective levels/tutorials for teaching and manage to improve engagement for players to finally end this aversion for game tutorials.

Bethesda Game Studios. (2011, November 11). The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. Maryland, USA: Bethesda Softworks.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. thematic analysis revised...

Capcom. (1993, December 17). Mage Man X. Osaka, Japan: Capcom.

Crawford, C. (2003). Chris Crawford on Game Design. Indianapolis: New Riders.

Creative Assembly. (2000, June). Total War (series). Sega.

Creative Assembly. (2011, March 15). Total War: Shogun 2. Tokyo, Japan: Sega.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: the psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York: BasicBooks.

Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House.

Eurogamer. (2015, September 7). Miyamoto on World 1-1: How Nintendo made Mario's most iconic level. Retrieved from Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zRGRJRUWafY

Fan, G. (2012). How I Got My Mom to Play Through Plants vs. Zombies. Game Developers Conference. San Francisco: Popcap Games.

Frensch, P., & Rünger, D. (2003). Current Directions in Psychological Science . Implicit Learning.

FromSoftware. (2006, June 29). Chromehounds. Tokyo, Japan: Sega.

FromSoftware. (2011, September 22). Dark Souls. Tokyo, Japan: Namco Bandai Games.

Gee, J. P. (2004). Learning by Design: Games as Learning Machines. Retrieved from Gamasutra: https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/130469/learning_by_design_games_as_.php

Gee, J. P. (2005). Good Video Games and Good Learning.

Gee, J. P. (2007). Good Video Games and Good Learning: Collected Essays on Video Games, Learning and Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Gillebaart, M., Förster, J., & Rotteveel, M. (2012). Mere Exposure Revisited: The Influence of Growth Versus Security Cues.

Huitt, W., & Hummel, J. (2006). An Overview to the Behavioral Perspective.

Jiménez, L. (2003). Attention and Implicit Learning. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and Effort. 11.

Karpicke, J. (2012). Retrieval-Based Learning: Active Retrieval Promotes Meaningful Learning.

Nintendo EAD. (2002, December 13). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. Kyoto, Japan: Nintendo.

Nintendo R&D4. (1985, September 13). Super Mario Bros. Kyoto, Japan: Nintendo.

Palladino, L. (2011). Find Your Focus Zone: An Effective New Plan to Defeat Distraction and Overload. Atria Books.

Sörqvist, P., Stenfelt, S., & Rönnberg, J. (2012). Working Memory Capacity and Visual-Verbal Cognitive Load Modulate Auditory-Sensory Gating in the Brainstem: Toward a Unified View of Attention.

Sweller, J. (1994). COGNITIVE LOAD THEORY, LEARNING DIFFICULTY, AND INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN.

TED. (2008, October 24). Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi: Flow, the secret to happiness. Retrieved from Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fXIeFJCqsPs

Yeomans, J., & Arnold, C. (2013). Teaching, Learning and Psychology. Taylor and Francis.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like