Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

That Dragon, Cancer tells the story not only of a child's death, but of the parents' struggle with faith, and their decision to keep believing. It's a very rare topic for games, honestly and observantly told, not capitalizing on a tragedy.

This post originally appeared at Emily Short's Interactive Storytelling and is reprinted here with slight editing.

That Dragon, Cancer is a game about the slow, painful, and confusing death of the author’s son by way of a rare cancer.

It tells its story through a series of vignette levels; in each, you have restricted navigational options to explore a 3D space, while audio and in-world manifestations of text fill in what is going on in the family at this point. Often you can hear the conversations of people whom you cannot see, which gives the sense of a ghostly dissociation.

The mechanics vary: sometimes you’re there only to look at a set number of things before triggering an advancement; elsewhere, you actually need to complete some small task, such as running a not-too-difficult platformer. Sometimes you need to spend a certain amount of time in a space with a screaming child in pain, and not be able to do anything about it. This is not a remotely pleasant or play-like experience, which of course is the point. But I often did feel that I was being offered an experience I haven’t seen anywhere else in games.

The dialogue is in general extremely naturalistic and plausible, and feels like it could have been transcribed from the author’s experiences: here is what the doctor says when handing down a diagnosis. Here is what you say to your other children when you’re all setting out for a hospital in another state, in a last-ditch attempt at saving their brother. Here is how you serve a juice box to a child too ill to keep liquid down. It is pitilessly, heartbreakingly mundane.

I was less enamored of some of the philosophical voiceover bits. In places it felt as though the author was going for a lyricism that was outside his usual range. I feel like this is a difficult point to criticize, though: who am I to say that a particular mental image could have been better chosen? This is documentary. This is the actual mental image the author had. So instead I will say this: I was more moved by the specific observations than by general metaphors of loneliness and fear.

That specificity sometimes goes in a direction that may be surprising. There is a passage where Joel is riding a wagon around a racetrack, collecting pills and other symbols of chemotherapy. It is giddy and cartoonish, and I know that it struck some players as strange. But that too felt like it was saying something true and perhaps surprising about cancer: in a terrible situation that persists for a long time, the participants often develop a beyond-black humor about it; a humor that is still 99% grief and rage.

Joel himself doesn’t speak much. The game explains early on that, having been sick since the age of one, he hasn’t followed the usual child development trajectory, so even at four, he’s not very articulate. He does giggle, and clap characteristically when he is happy; and he cries when he is in pain. But that is as much of his perspective as we can really get at. What we see is mostly the inner lives of his parents.

A non-trivial portion of That Dragon, Cancer is about the parents’ struggles of faith. I found this very interesting and I want to talk about it, but I feel more than usually cautious about doing so because I don’t know these people personally. So in talking about Joel’s father Ryan and his mother Amy here, I am referring to the characters in the game, and the way I interpreted the text about them. What real-life Ryan and real-life Amy think, I don’t presume to know or judge.

So. They are coming from a denomination of Christianity that places a fair amount of emphasis on healing miracles. Amy believes firmly up until Joel’s death that God is going to come through and save their son. Ryan is less certain. Much late-game tension is about the distance between Amy’s certainty and Ryan’s more tentative hope. The game doesn’t explicitly come out and say this, but I wondered whether the character of Amy thought that she needed to expect a miracle because expecting the miracle was the act of faith that would bring it to pass. As for Ryan, his doubt is bound up with feeling that he just isn’t important enough for God to care about his son specifically.

There is a level near the end where you are lighting candles in a church while the audio plays snippets of prayers for healing. The candles keep going out. I kept relighting them in a relentless spiritual whack-a-mole. It is a moment that, at least for me, used mechanics that I would ordinarily associate with gonzo humor and perhaps parody, but to express something unbearably bleak. The miracle is not coming. Can we keep our faith alight even in its absence?

But despite these elements, That Dragon, Cancer features comparatively little direct questioning about how a just, loving, and omnipotent God could allow childhood cancer to exist in the first place. That might seem the obvious trope for this story to explore, but most of the content is about these other concerns.

The game ends on an upbeat, almost evangelistic note that startled me. Joel has died, but the narrator still waits in hope for clarity about what God intends, what God means by it all. It seemed to me that at least the characters of Amy and Ryan didn’t continue believing in God because they’d come up with any particular theodicy that would reconcile his existence with Joel’s painful death. It seemed to me that these characters continued believing because they chose belief.

In this I was reminded of this passage from a speech Obama once gave, before his presidency, about faith and politics:

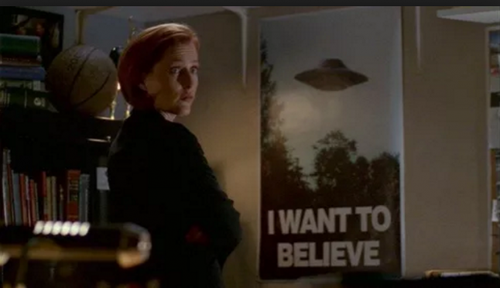

And it also reminded me of this:

I realize this may seem like a flippant juxtaposition, but I really don’t intend it that way. Little grey men notwithstanding, X-Files is a show about faith, and conviction in things not seen – Mulder’s faith in paranormal phenomena, Scully’s Catholicism, and eventually their faith in each other. It wasn’t always well-written, didn’t always make sense. But it wasn’t precisely anti-science in the simplistic way that evangelical Christians are often portrayed as being anti-science. It wasn’t simply about faith as a way to escape consensus reality, though that issue does come up. It was also often about choosing faith as a way to make some moral order out of a world that seemed otherwise incomprehensibly strange, unjust, and hopeless.

The hopeful post-death tone of That Dragon, Cancer surprised me when I first experienced it, but as I thought about it more, it seemed to be about some of the same type of thing.

This is a really sad, really un-fun game; you have to know that, going in. But it is not only sad and un-fun. It is not a Lifetime TV special; it doesn’t exist solely to tug the heartstrings. It tells the story of some things that would be unimaginable if one hasn’t had those same experiences; the story of people with a particular type of strong faith who have that faith put to an extreme test, who are nearly drowned by despair, and who come out still believing. That part may not resonate with everyone, but it’s a kind of story I’ve almost never seen in this medium.

Disclosure: I played a free beta version during the course of IGF judging.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like