Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

| Picture Perfect: Exploring Photography Games | ||

| Every day this week, Game Developer is serving up a gallery of interviews, deep dives, and more digging into the evolution of Photography in video games. | ||

| Browse Latest Articles | Submit your Blog | |

Join us from 9/16-9/20 as we examine the photography genre and explore what developers can learn and apply to their own projects.

Photography has become one of the most popular ways we interact with video games. Through the simple act of taking a photo, photography games and photo modes implore us to notice our surroundings, document our experience, and take a moment to commit to memory the images and emotions that we felt along the way. As Game Developer launches its Photography Week, come along with us as we take a quick look at the history of photography in video games and its popular uses within the genre and preview the new interviews, essays, and deep dives publishing in the days to come.

In video games there are two primary ways we experience photography. There are games in which photography is the primary gameplay element, used to structure a narrative or add puzzle-based progression. And there are games that have photo modes, giving players tools to make and edit the perfect photo within the world they’re immersed in. Over the years, as graphical fidelity has evolved, so too has the demand for in-game photography; it seems like almost every open-world game has a photo mode these days. But players embraced the mechanic long before graphics had the ability to make their photos actually look good, going back at least as far as the N64 era. Look no further than Pokémon Snap.

Pokémon Snap as it appears on the Wii virtual console. Image via Nintendo.

Originally an N64 title, Pokémon Snap was an on-rails experience that let players take “candid” Pokémon photos in a controlled, open-air environment, much like a wildlife safari. The resulting photos weren’t particularly pretty or artistic (and famously failed to adhere to basic photographic principles), but the game was smart in that it addressed an early issue in photography games by controlling the player’s movements and line of sight, avoiding the staggering technical costs of facilitating spontaneous Pokémon interactions in an open world. It would be many years before the game would see its sequel, New Pokémon Snap, but in the meantime, it would inspire many games, establishing a format that would be seen in so many later titles both directly and indirectly.

Games like Penko Park, Alekon, and Beasts of Maravilla Island (all of which we’ll discuss later this week) would make their own spin on photographing a collection of creatures, sometimes adding an element of puzzle-solving to encourage new poses or scenes to add experiential variety. And many games with photo modes, from The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild to the building game Grounded, use a compendium to help the player keep track of the plants, animals and other items they’ve snapped in the game, sometimes to convey information about their environment or how they can be used in crafting or cooking.

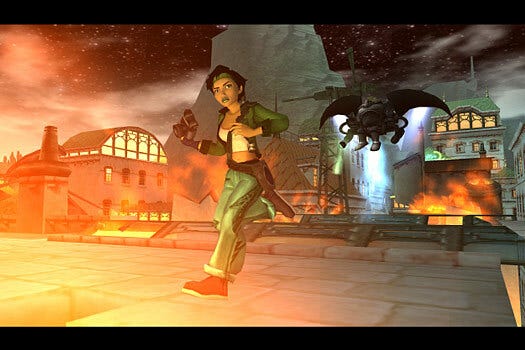

Image via Ubisoft.

Other notable and influential games in the genre focus on the recurring themes of documentation, not just of biological species, but in terms of photojournalism, from the heroine Jade in Beyond Good & Evil, to the antihero Frank West in Dead Rising, to journalist Eric in safari photo game Afrika. In more contemporary times, we have games like Umurangi Generation, a game that uses the documentation of the apocalypse as a metaphor for corporate whitewashing in the face of climate change. There’s also Pupperazzi, which combines photojournalism and species documentation to humorous effect by turning the player into a candid photographer for dogs. And there’s the more voyeuristic and modern take on documentation in The Crush House, which positions players as the videographers on a reality show. You can read a deep dive into that and how the devs approached the subjectivity of a film clip rating system later this week.

Screenshots from the original Fatal Frame on PlayStation 2. Images via Tecmo.

In terms of games that center photography in their gameplay, historically there is Fatal Frame, which famously used the camera to detect and photograph ghosts, a theme of revealing hidden truth that continues in horror to this day. For example, in Outlast, the camera is used to emphasize the journalist Miles Upshur’s vulnerability as he documents the horrors inside a psychiatric asylum. In many minigames and lighter contemporary titles like TOEM, the camera is a puzzle-solving tool, used to find and photograph items at the behest of secondary characters or reveal obscured information. And building on the direct link between photography and gameplay are games like Camera Obscura, a platformer where players solve puzzles by assembling environmental elements from still photographs, or Viewfinder, which similarly “reshapes reality” by manipulating photographed objects.

Image via Thunderful Publishing.

As far as photo modes go, these days, they’re so ubiquitous as to be an expected game feature; more recently, games like Pacific Drive and Dredge have added photo modes in post-release updates, and open-world titles like Horizon Forbidden West or Cyberpunk 2077 use them to add value to the expanse of their environments or to help players tell stories through their characters. And it’s not just in 3D games—take, for example, A Highland Song, whose depiction of the Scottish highlands and its accompanying photo mode are entirely in 2D (stay tuned for a discussion on that tomorrow).

It’s also fascinating to note the role that early PC games played in the rise of the photo mode’s popularity. Before photo modes became the standard in scenic open-world titles, fans of games like Fallout: New Vegas and The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim were using console commands and mods (including lighting and weather effects, poses, and animations) in combination with screen capture devices and software to take photos outside the limitations of fixed visuals and in-game camera systems, leading to the more formal tools seen later in Fallout 76. Meanwhile, young players of The Sims in the early 2000s used photography (facilitated by an in-game camera tool) to document and tell stories about the lives of their Sims characters, relying on the interactions of the game’s complex trait systems to provide intrigue and spontaneity. This, in turn, paved the way for modern-day, user-made game entertainment, from game streamers to machinima. Player photography has had a major impact on how and why we use photo modes—or even have them at all (you can read more about this in part in our staff blog later this week).

If this topic fascinates you, there’s still time to submit an article to our blog section about photography games and photo modes in video games. Take a peek at our blog submission guidelines and FAQ, head over to our blog submission page and send us your thoughts. We’ll be highlighting reader-submitted articles throughout the week and there’s tons of great stuff to look forward to, like an essay from Beasts of Maravilla Island developer Michelle Olson about eschewing photographic critique, an interview with the developers of Texas Chainsaw Massacre on why they went with the free release of an idyllic photography minigame as a prequel to their horror title, and a poignant feature from our senior editor Bryant Francis on what basic photography tips can teach us about making better photo modes.

We’ll also be revisiting interviews, blogs and features from Game Developer’s recent past, unearthing postmortems from games like Pupperazzi and TOEM as well as interviews with indie developers about how they’re using photography in video games. Stay tuned for insight on how these games are put together and the features that developers find vital to the photography game experience.

Read more about:

Top StoriesYou May Also Like