Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

An attempt at exploring, critically discussing and eventually defining what responsive narrative is and its value as a tool in the repertoire of any narrative designer.

The only way to win your player over is through their emotions.

David Hume wrote in 1739: “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”

He was formulating this regarding what one needs to truly win someone over in an argument. But much of classic rhetoric knowledge can be applied to modern-day storytelling, especially since we narrative designers are faced with the daunting task to hook into and evoke our player’s emotions in an interactive medium while not limiting their player agency over it.

We can’t force someone to feel and we can’t force someone to understand, but what we can do is lead them with us in the same direction so delicately that they might not even notice they’ve been lead. We want the player to think “Aha! I’ve done it!” or “I can’t believe this is happening!” We want to stoke their sense of wonder and induce an autonomous response. Quoting then Last Of Us designer Peter Field: “A good game mechanic is something that makes the player feel clever, not something that shows off how clever the designer is.”

Now to ask ourselves a critical question:

If a game can be “lets played” and everyone watching will have the exact same story unfold as if they had been playing it themselves, is that still truly a game? Or an interactive show of some sort, is that still playful at its core? How can we make sure our game, our interactive experience, stays playful while still delivering that powerful emotional response that we know and love so much from all kinds of prose, be it in film, television or books.

The answer is responsive narrative, but what is that? And how do we make use of it?

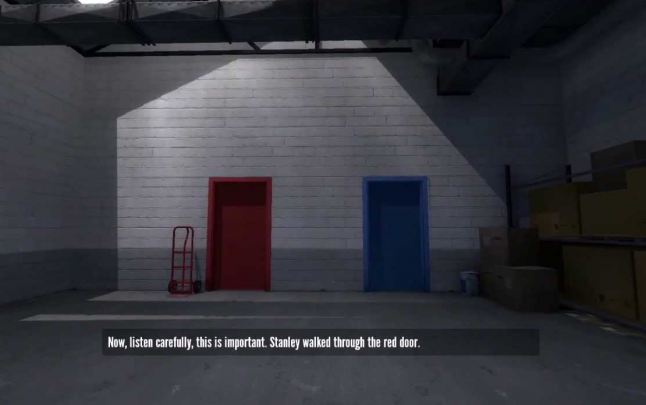

I think a big part of the question rests on the assumed definition of responsive and how direct or indirect it is allowed to be before it's not considered responsive narrative anymore. Let’s explore the question by example: Stanley Parable, arguably one of the most narratively responsive games ever, bases the entirety of its announcer plus voice in your head, level progression and endings solely on what you as a player decide to do or not do. It’s not necessarily an open world game but rather an amalgamation of many linear progression strings tied together through complex timings. Then there are games like The Witcher 3, Skyrim or Red Dead Redemption 2, where the passive narrative in the world is mostly affected by your actions. I.e. kill important NPCs - suffer consequences (reputation loss, different reactions to your character, alternate ending slides) So now, where is the line? At which point does a narrative stop being responsive? If I knock over a flowerpot and the NPC can’t place flowers in it anymore, is that still responsive narrative? Or does it need to have grave consequences? Like knocking down the food rations and someone in your camp dies of starvation because of it who would otherwise still be able to provide you side quests. Or is a responsive narrative only any narrative, that’s directly based on active choices and that the player must fully be aware of the choices and their consequences before committing to them? A typical example quite literally being a question prompt asking the player:

what you as a player decide to do or not do. It’s not necessarily an open world game but rather an amalgamation of many linear progression strings tied together through complex timings. Then there are games like The Witcher 3, Skyrim or Red Dead Redemption 2, where the passive narrative in the world is mostly affected by your actions. I.e. kill important NPCs - suffer consequences (reputation loss, different reactions to your character, alternate ending slides) So now, where is the line? At which point does a narrative stop being responsive? If I knock over a flowerpot and the NPC can’t place flowers in it anymore, is that still responsive narrative? Or does it need to have grave consequences? Like knocking down the food rations and someone in your camp dies of starvation because of it who would otherwise still be able to provide you side quests. Or is a responsive narrative only any narrative, that’s directly based on active choices and that the player must fully be aware of the choices and their consequences before committing to them? A typical example quite literally being a question prompt asking the player:

Do you want to intervene?

A) No! Never! - Some guy dies

B) Yes of course! - Some guy doesn’t die.

Because if we don't draw a line, basically any game's narrative is a responsive one, given the medium’s interactivity.

Let’s have a look at a different example from 2013: Tomb Raider. The game is already well known and critically discussed for its strong ludonarrative dissonance, as in Lara caring deeply about humans and animals  alike while in cutscenes (the image depicts her in the infamous deer killing scene), almost not being able to kill anything or let anything die, yet during gameplay, she (the player) has no problem murdering hordes of hired hands just manning posts on private expeditions while Lara is sporting quirky barks.

alike while in cutscenes (the image depicts her in the infamous deer killing scene), almost not being able to kill anything or let anything die, yet during gameplay, she (the player) has no problem murdering hordes of hired hands just manning posts on private expeditions while Lara is sporting quirky barks.

The more important aspect for our question is its complete lack of player influence on the story. Sometimes the game presents an illusion of interactivity, yet never follows through offering meaningful influence on how the narrative unfolds. Just like Uncharted both games are still immensely fun, stunning adventures proving that while the narrative is unresponsive, as long as proper expectations are communicated and the player is aware of what he is in for, a guided almost railroaded experience, the game’s core fun isn’t affected. What we learned is, that as long as you can’t influence the narrative as a player, the narrative is not responsive.

But what if the intended goal is indeed a more open world yet also a more immersive experience? Our focus as designers must lie on cohesion. Both small scale (The Witcher 3: wearing the right clothes) and large scale (The Witcher 3: conversing with an emperor) events must be considered by each other in order to not break the veil that is upheld by our wondrous fictional world. With the increase of the game’s size so does the difficulty to achieve that. The player’s character gains knowledge in some side quest involving one of the main cast's acquaintances and now if anything related to that information is ever disregarded by any of the other story threads going on involving that character, then the atmosphere and illusion of our world that we spent so much love and effort crafting might ring dissonant.

This naturally leads us to the topic of meaningful choices, because if one moral tiny error in the player’s choices could lead him to an entirely different ending, did his other choices up until this point really matter?

An exercise for the reader:

Which is the better structure and why:

A) Having hundreds of decisions including text prompts (similar to the singular Witcher event prompts like saving someone) and just how you treat NPCs, how you handle side quests or if you even do side quests. Do they influence a hidden scale (good; neutral; bad alignment) and does that influence where your narrative is going? A system of rewarding virtue if you will.

Or:

B) Just a few major black and white decisions so players don’t have to stress while playing and can experiment freely without remorse or fear of consequences.

While one might be inclined to pick either, the answer is much rather neither. There is an equilibrium to be found here between A) and B) because as it stands, in a large game production, A) is close to impossible to achieve and the individual choices feel meaningless and B) is too heavily loaded and not satisfying enough. Your character taking drastic turns on a single decision realistically makes no sense (Murder all NPCs the entire game, choose the one important do good option in the main quest and get the good player ending?)

Additionally, it’s hard to motivate players to do tasks that provide less narrative payoff (helping a farmer does not deliver the same satisfaction as unveiling a grand scheme mystery). Even more surprising is that Fallout’s choice design adopted a minimalist mindset over the years. From deep branching dialogue trees to a moral compass offering “yes”, “no”, “maybe” and sometimes sarcastic options of the former, which shifted their design pillar to prioritizing understanding of the consequences.

Upcoming open world RPG Cyberpunk 2077 offers the player complete agency over the fact if he wants to be lethal, non-lethal, stealthy, or violent. The problem upholding coherence in stealth supporting games often manifests itself in boss fights not being solvable by stealth, which in turn devalues the narrative the player has built for himself inside our narrative.

One of my favourite games, while demonstrating phenomenal environmental storytelling and intuitive game design, Dishonored, delivered an amazing set of choices to immerse the player in the narrative and truly communicate and respect the player’s agency. Also furthering replayability since you want to see what happens if you do not save her, do not hold her hand. Everyone can be creatively killed or spared in multiple approaches with direct consequences as to how the story unfolds while still offering RPG like skill progression and a lot of passive (NPC chatter, journals, letters, voices etc.) and active narratives.

To close out I’d like to quote Thorsten Becker, pinpointing the intended experience using responsive narratives: “It becomes more than a story, it becomes my story even though ultimately resolved into one of several pre-set endings. But I reached it solely on my own agency.”

And that is exactly what we want. We want the player to feel.

Thank you for reading and if it wasn’t already, I hope responsive narrative has now found its way into your tool belt. I’d love to hear about your opinions or how you are dealing with building an immersive world on any of my socials:

https://twitter.com/samluckhardt

https://www.linkedin.com/in/samluckhardt/

Stay healthy out there,

Sam Luckhardt

Game & Narrative Designer

CD & CEO

https://tonkotsu.games/

Host

https://industryidiots.com/

Big thank you to Edwin, Thorsten, Jerf, Kwayzy and Hian from the narrative design community for participating in the discussion and Edwin McRae for prompting the question in the first place.

If you'd like to join me and other industry professionals from AAA and Indie for discussions about all things narrative design and game writing in a cozy, friendly community, then drop by the Narrative House Discord and say hi. Make sure to send me an accompanying message with it so we don't mistake you for a bot and know how you found your way into the community.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like